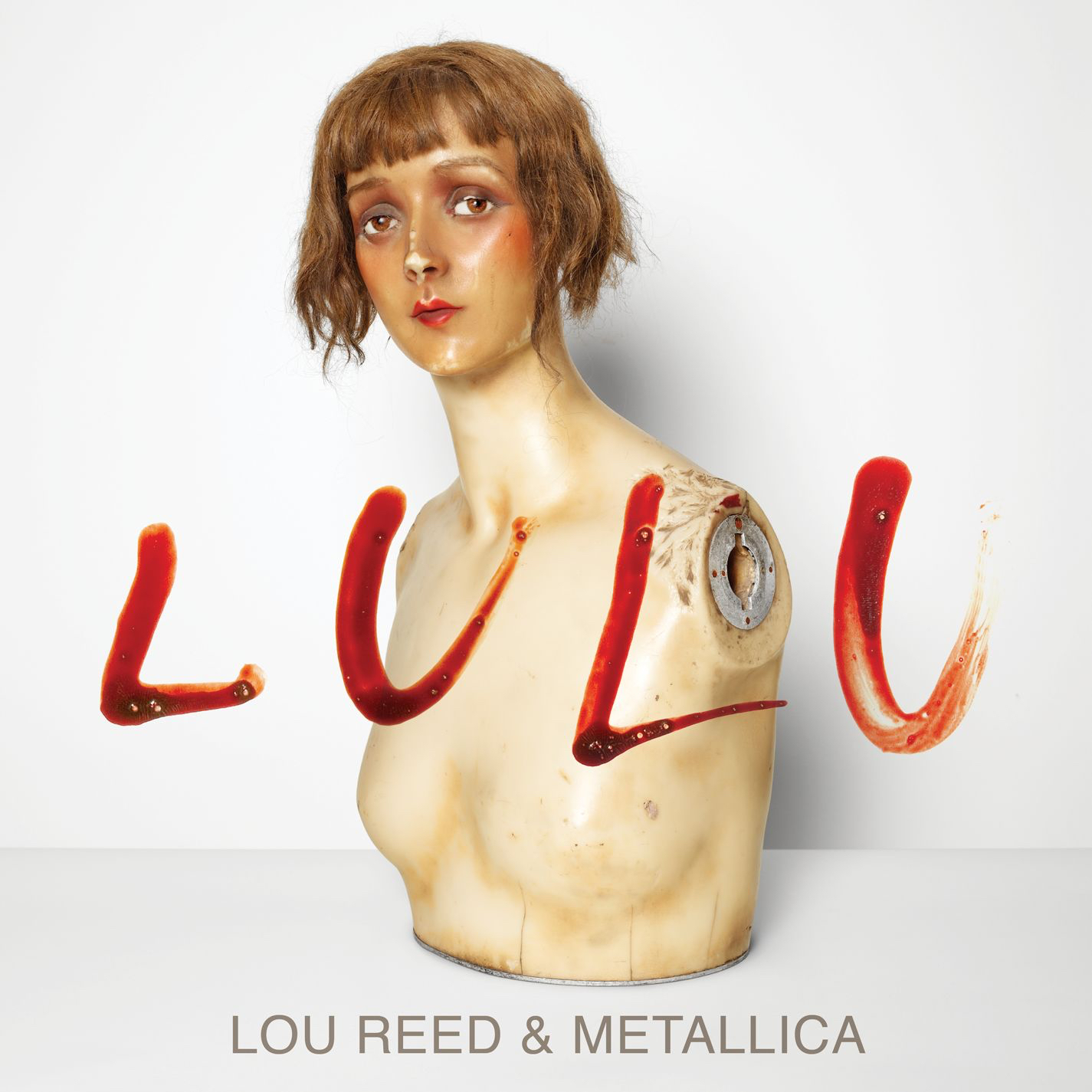

- Warner Bros./Vertigo

- 2011

Lou Reed and Metallica got together. It was not a successful collaboration. The Bay Area hard rock band had been recruited to perform behind Reed at the 2009 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame 25th anniversary concert -- where they also accompanied Ozzy Osbourne and the Kinks' Ray Davies -- and they showed up in full force, bringing a crunchy heft to "Sweet Jane" that made the Rock 'n' Roll Animal version, merciless enough in its own right, sound gentle. Things went well enough, but in hindsight Reed and his close collaborator Hal Wilner found the band's playing "too militaristic" according to Anthony DeCurtis' biography Lou Reed: A Life. Still, there was something about the arrangement that sparked Reed's curiosity. His recent experiments with Sarth Calhoun in Metal Machine Trio had recently veered into heavy sonic territory, offering a discordant and distorted counterpoint to the becalmed Tai chi ambient music of his 2007 album Hudson River Meditations but perhaps spiritually aligned with its long, drifting sprawl.

What followed was Lulu, a double-disc collaboration between Metallica and Reed. Released on Halloween 2011 -- 10 years ago this Sunday -- it would be Reed's final work before his death from liver disease almost exactly two years later. Lulu was a confounding and difficult record, loaded with strange misshapen riffs, unrelenting rhythms, modern classical interludes, and thematic depravity adapted from the shocking and controversial "Lulu plays" of Frank Wedenkind: Earth Spirit and Pandora’s Box. A decade later, Lulu still confounds, the conclusion of a career that proved profoundly challenging until the very end, from an artist who sought to remain fully engaged, perfectly content to baffle his audience if it meant following his imagination. Like the late career team team-ups of Scott Walker and Sunn O))) and David Bowie with the Blackstar band, it's the work of a creator in the grip of life-affirming creative fervor. Ten years on, the album stands as an ugly, uncompromising art-rock ode to flesh and messy humanness, an expression of avant-metal and amplifier worship paired with stomach turning evocations of mutilation, shame, and degradation -- violence marring Reed's final hour, to paraphrase a line in "Iced Honey." But at key moments, poignant beauty nonetheless shines through, the work of an artist and engaged collaborators determined to wring the last bits of his life from his “coagulating heart."

Reed came to Metallica at a strange moment in the band's career. Though they'd returned to a traditional metal presentation with 2008's Death Magnetic -- their first album to feature new bassist Robert Trujillo alongside guitarist/vocalist James Hetfield, drummer Lars Ulrich, and guitarist Kirk Hammett -- the band's previous two decades had been marked by experimentation. In 1991, "The Black Album" opened the thrash band up to a wider audience, and subsequent albums Load and Reload found them meeting the rise of alternative radio head on. They'd teamed with a symphony and conductor Michael Kamen on 1999's S&M and attempted, valiantly if not so successfully, to deconstruct their sound on 2003's St. Anger, which was accompanied by the truly great rock & roll documentary Some Kind Of Monster. On screen, the bandmates struggle to creatively inspire each other, leading to moments of meme-able emotional wipeout ("Delete that.") and scenes of painful and earnest intra-group communication.

In attempting to avoid "stock" ideas, Metallica had challenged its audience, but just as much so its own members. In the '90s, the band cut their hair, and along with that ultimate metal betrayal, Ulrich and Hammett encouraged gothy makeovers, Anton Corbjin photo shoots, and controversial artwork choices: Load featured Andres Serrano's Semen And Blood III on its cover, an artwork in which the creator’s semen was mixed with cow blood between plexiglass, which led to Hetfield decrying his bandmates’ artistic pretense and conversations about Hetfield's homophobia spilling over into interviews. Still, the band's restless creative dynamic demonstrated a group that didn't want to play things entirely safe. Teaming up with an elder statesperson wasn't even new for the band, but joining forces with a creative of Reed’s stature was no doubt appealing. Reed certainly saw in the group a powerful sonic generator; their moxie and willingness to explore probably didn't hurt either.

That said: Lulu is not what Metallica had signed on for. Initially, Reed and Wilner pitched the band on the idea of joining Reed to resurrect gems he'd scrapped over the years. But the concept was abandoned late in the game, when Lou heard metal riffs Calhoun had added to the more ambient work they'd created for Robert Wilson's stagings of Wedenkind's plays. Just before recording was scheduled to begin at Metallica HQ in April of 2011, Reed suggested a shift in direction. You really have to wonder what a more traditional Loutallica album might have sounded like, if perhaps Load-era productions like "Hero Of The Day" and "Until It Sleeps" were paired with the savage lyricism and minimalist power heard on Reed's guitar-heavy albums like Set The Twilight Reeling and Ecstacy. What Reed was proposing was decidedly not that, but Metallica, to the band’s immense credit, was game to give it a go, serving as producers alongside Lou, Wilner, and Greg Fidelman.

From April to June, the band worked, joined by Calhoun working electronics and a string section providing additional sweeping grandeur to the overblown guitars and churning bass. It wasn't exactly a breeze -- at one point Reed challenged Ulrich to a fist fight and struggled with Hetfield when it came time to interject obtuse lyrics and his signature yarl into Reed's mostly spoken cadences -- but by the end, they had created something they were deeply proud of. "Lou Reed is the godfather of being an outsider, being autonomous, marching to his own drum, making every project different from the previous one and never feeling like he had a responsibility to anybody other than himself. We shared kinship over that," Ulrich told The Guardian in 2013. "We brought something to each other, and we shared a common lack of ability to fit in with our surroundings."

Reviews grappled with the album's weight. Writing for Pitchfork, Stuart Berman deemed Lulu a "noble failure" and assigned it a 1.0 numerical score (it was not recently re-rated), though The Wire's David Keenan called it"the ultimate realisation of Reed's aesthetic of Metal Machine Music..." In a review evoking Tim Tebow, "The Red Hot Chili Peppers covering the 12 worst Primus songs," and Occupy Wall Street, Chuck Klosterman met the album's cruelty and violence more than halfway, lamenting with a kind of glib, dismissive humor of the day what a bummer it is major label executives and corporate interests were powerless to stop the album's release. The Wire's Jennifer Lucy Allan called the reception to the album a testament to Reed's way of getting "under the skin of even the most open-minded listeners," an ability he retained even as he entered his 70s.

A decade later, Lulu remains mystifying and, rightly, a hard sell. It includes lyrics that make your stomach twist, detailing rivers of gore, objectifying racial tropes, misogyny, and impotent groveling. "Every meaning you've amassed like a fortune/ Oh, throw it away/ For worship of someone who actively despises you," he sneers on "The View," and Reed frequently seems to despise the listener on Lulu, though never as much as he seems to despise the characters in these songs. Even when the songs contain hooks -- and contrary to popular opinion, there are passages that qualify, like the charging "Brandenburg Gate," with Hetfield’s impassioned "small town girl" refrain, or "Iced Honey," a two-chord stomp that offers a slight reprieve of swing and levity, Reed "keeps unbalancing you," intent on instilling a narcotized wooziness and uneasy tension. In this dark mode, Reed’s compositions demand the "listener sit with the ugliness of a moment and really grasp the fatal mistakes and collapses that go hand-in-hand with the risks that bring humans to life," like Ann Powers surmised in "What Lou Reed Taught Me." On Lulu, he intently scars the notion into the listener, sacrificing himself on an altar as an object lesson.

It all builds up to the nearly 20-minute closer, "Junior Dad." Generally speaking, it's the Lulu song that even those who mostly find the album distasteful can nod along to. Reed’s antagonism with his father marks his discography, but over an entwined and mesmeric riff, Reed gives up the Oedipal ghost. "Age withered him and changed him/ Into junior dad/ Psychic savagery/ The greatest disappointment/ The greatest disappointment/ Age withered him and changed him into junior dad." Metallica plays it like an elegy, Lou intones graceful murmurs, and eventually, the featured artists drop out, opening space for a long stretch of celestial strings. It is a profoundly moving composition, up there with "Street Hassle" in its majesty. Reed and Metallica's collaboration may have started an onstage near-miss at the Rock Hall concert, but observe their 2011 Rockpalast take on Lulu’s closing song: Ulrich, Trujillo, Hetfield, and Hammett seem tapped into a vibrating frequency, eyes closed in spiritual harmony:

Lou Reed maintained a generous contemporary profile in his final years, creating stirring work with ANOHNI, the Killers, Gorillaz, Metric, and others. But nothing of his closing days showcases the vitality and ferocity of his spirit the way his collaboration with Metallica does. To muster up what he needed for the record, he needed Metallica, a giant band with giant willingness, a need that makes its way into the record itself. "Come on James," Reed gasps at one point. "This is his masterpiece," David Bowie told Laurie Anderson after Reed's death. "Just wait, it will be like Berlin. It will take everyone a while to catch up." Anderson's own take on Lulu was just as flattering: "It's written by a man who understood fear and rage and venom and terror and revenge and love. And it is raging. Anyone [who] heard Lou sing 'Junior Dad' will never forget the experience of that song, torn out of the Bible. This was rock & roll taken to whole new levels." In the recent Todd Haynes documentary The Velvet Underground, the filmmaker explores how Reed began his career aspiring toward creative transcendence, time bending, and the notion of rock music as literature. Beyond the flesh and cruelty of Lulu, it is an album about animating lifeforce. Through this crucible of pain, Reed offers a glimpse of something divine. It is very hard to look at.