- Jive

- 2001

Twenty years ago Britney Spears recorded "I’m Not A Girl, Not Yet A Woman." A goopy piano line and a karaoke-bar drum machine preset signal its seriousness. She and producer Max Martin wanted a ballad manifesto for Crossroads, a road-trip film about being Britney Spears but with Dan Aykroyd as the father resisting her maturation. For their idea of sensitive lyrics they tapped Dido Armstrong, whose "Thank You" turned into a massive hit in its own right after Eminem's fan-ambivalent "Stan" interpolated its chorus. Recorded in Stockholm with Martin's crew, "I'm Not A Girl" boasts a solid Spears performance; she sings the words in her thin, whiskery, fey timbre. She sounds like neither girl nor woman: She sounds as if the pitch-altered Prince of "U Got The Look" had imitated a senior citizen. The result is weird, powerful, and listenable -- check out that key change in its last third, where she goes for it -- if not quite a triumph.

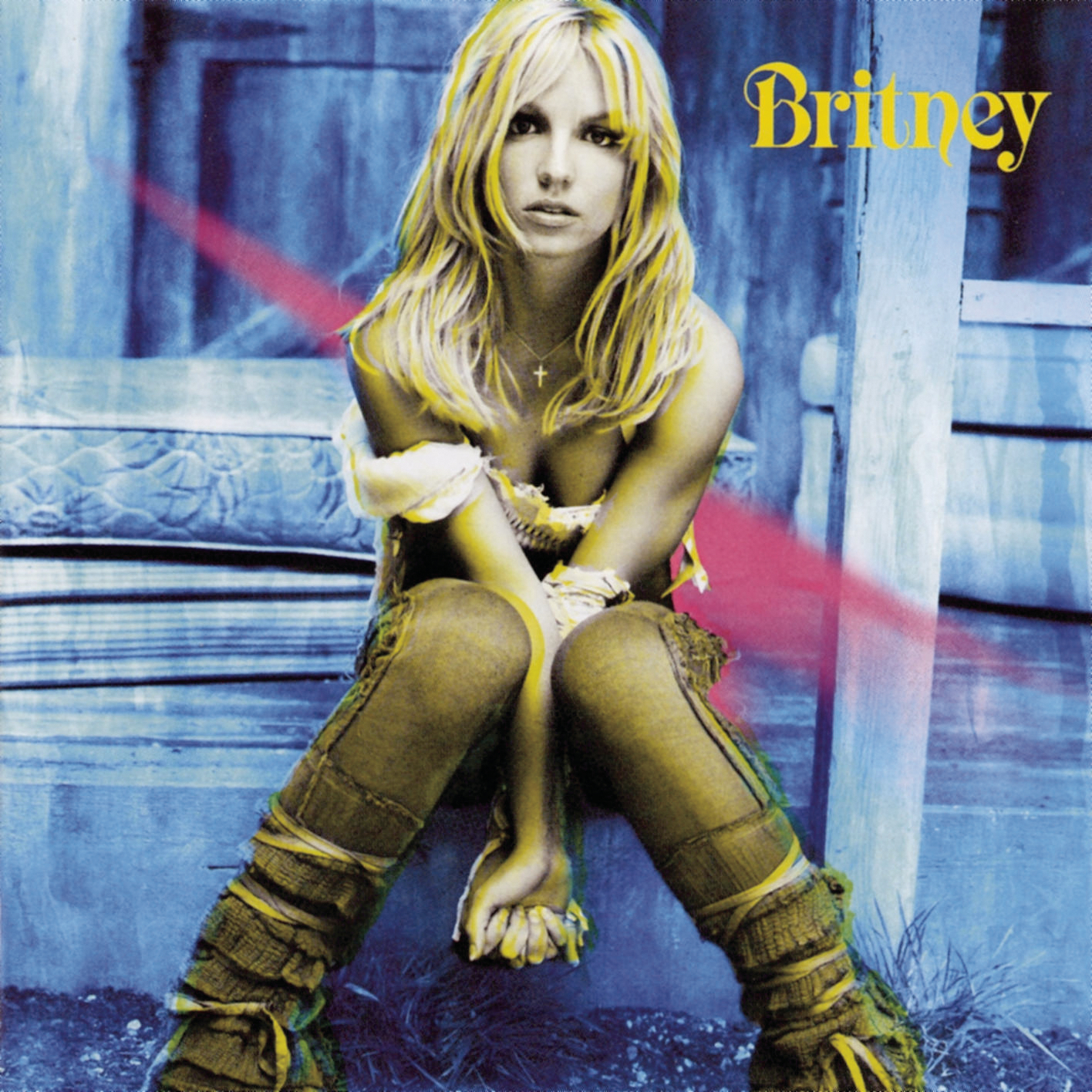

"Weird, powerful, and listenable" also describes Britney, the album Spears released the last week of October 2001, 20 years ago this Saturday. Not quite a triumph either. Fizzing up the giddy aerobicized climaxes of Martinized grease-free pop with crucial songwriting/producing contributions from the Neptunes, Spears wanted what every pop star since 1983 had done when they conflated maturity with sexual availability. But she couldn’t get Prince in 2001 -- No Doubt got him first, sorry. Instead, she got Pharrell Williams and Chad Hugo at the apogee of their first fame.

You know who also reached his own apogee? An ornery, stupendously incurious governor of Texas whom the Supreme Court made president and who as president oversaw the most spectacular intelligence failure in American history. Despite the croakings of doom from traditional media types who while rubbing their chins pondered whether we had watched the death of irony, pop music during the 9/11 era was as glorious as the times were low and dishonest. The pop environment in which Spears released Britney was not escapist; it reflected the aspirations and lusts shaped by Total Request Live and Nightline as much as by consumer preferences -- same as it ever was.

But the multivalent conversation between R&B and hip-hop got those consumer corpuscles flowing. Occasionally the former got harder, the latter got softer. On the week Britney's biggest hit "I’m A Slave 4 U" peaked at #27, it shared chart space with Shakira, Alicia Keys, Mary J. Blige, Ja Rule, and Ginuwine. Slush-o-ramas like Enrique Iglesias’ “Hero” and Enya’s tidal love-is-the-seventh-wave “Only Time” were huge too, indicative of the collective mourning. Creed’s garlic-breathed “My Sacrifice” too. Otherwise a ruthlessly concentrated and densely percussive frivolity reigned.

Adjacent to pop, though, reigned a sociopolitical culture which saw in George W. Bush’s response to the 9/11 attacks a tonic to the alleged libertinage of the Clinton years. The intersection of an encouragement of nubility in pop stars on one hand and sexual hysteria on the other that culminated with Attorney General John Ashcroft’s ordering a statue to cover itself resulted in dizzying paradoxes. America 20 years ago had a fascination with Britney Spears' age, as if listeners and tabloid columnists needed permission slips to acknowledge her attractions. Glossy magazine cover stories acted like unindicted co-conspirators. In an Entertainment Weekly cover story, the reporter makes the following remarks:

To be honest, it’s hard to tell if "doing her thing" includes playing coy or if she’s swept up in some cultural debate even she can’t begin to fathom. Her Crossroads director, Tamra Davis, thinks Spears is an active participant in the virgin-whore gambit: "She definitely plays with that duality." But for her part, Spears wants you to believe that she’s shocked -- shocked! -- by the barely-legal brouhaha that has been swirling around her ever since she shook her moneymaker through the Lolita-in-a-plaid-skirt "…Baby One More Time" video.

The implication -- Spears is too dumb to acknowledge the spot she’s in -- jumps off the page. “I always had my own identity,” she says in the same interview. “I’m an entertainer when I’m on stage... and they need to explain that to their kids. That’s not my job to do that.”

Had this interview appeared in spring 2000 during the promotional cycle for her second album Oops!... I Did It Again this purported coyness would’ve coincided with that title track’s is-she-or-isn’t-she fan dance. Studying the precedent of Janet Jackson’s marvel of steely electrofunk, the Jam-and-Lewis-aided third album Control (1986), Britney is strongest when she accepts she’s doomed to be misconstrued. On the Max Martin/Rami Yacoub-produced "Cinderella," Spears sings, "I’m sorry for running away like this/ But I’ve already made my wish.” The French house-pop of "Anticipating" shows her losing her bearings on the dance floor, the cover of “I Love Rock ‘N’ Roll” shows her savoring a heady car jam transformed into a constricted, practically airless chant suitable for the TRL studio -- how Spears as a child of MTV and the grueling Mickey Mouse Club circuit would’ve perceived Joan Jett, in other words. “Bombastic Love” repeats the cricks and cracks and squonks of “...Baby One More Time,” but already a shade of uncertainty darkens the aluminum foil crinkles of her voice: “Don't know why I feel so insecure/ I never understood what it stood for.”

Specializing in a post-Minneapolis funk whose whirring, popping minimalism works best with singers willing to exhale a lubricious sigh or two, the Neptunes contribute a pair of songs suited for Britney The Entertainer. Hugo and Williams’ bag of tricks on “Boys” includes triggered vocals and breaths over the stutter-bass popular at the time while Spears offers carnal smut about eyes and sexy hair. “I’m A Slave 4 U” is leaner: a chassis without an automotive shell. It makes period Timbaland tracks sound like Max Martin. Spears, a multi-tracked daisy chain of availability, is louder than the arrangement. Intended for and rejected by Janet Jackson, “I’m A Slave 4 U” requires a performer’s strategized image transformation -- it’s her "That’s The Way Love Goes."

To what degree Britney Spears as opposed to “Britney” had, to return to the interview cited earlier, her “own identity” and why she felt “so insecure,” her audience understands now. So quick are we who appreciate pop to assume its practitioners are self-willed people -- to project our untested notions of agency -- that we overlook what stands before us. We understand, in other words, how, in Katherine St. Asaph’s words, "several men are the literal bosses of her life." Spears was a slave. She couldn’t be a girl, much less a woman, when she was offered as an object.

If “I’m A Slave 4 U” was a discomfiting listen in 2001 (did she mean it?), try it now (oh, she did mean it). For doubters, behold “What It’s Like To Be Me,” on paper another ponderous affirmation but as song a scratchy, twitchy Timbo-influenced thumper co-written and co-produced by -- are you ready for this? -- Justin Timberlake. Branded as a hussy in Timberlake’s 2003 solo smash “Cry Me A River,” reduced to a punchline in a pathetic Omeletteville skit for SNL, Spears was a slave to this Brillo-haired Svengali’s fantasies too. Consider the weaselly manner in which Timberlake escaped censure after Jackson’s putative Wardrobe Malfunction in 2004; he kept giggling and smirking about it 14 years later. “More people would rather believe that Janet Jackson popped her own pastie off via some kind of impressively choreographed muscle spasm rather than consider Timberlake an active agent in the whole thing,” Lindsey Zoladz remarked in a reconsideration of the incident. If any credulous readers wonder about our progress toward gender parity, ask yourselves: would Justin Timberlake sing “I’m A Slave 4 U”? How much power would this vehement gladhander cede?

Conversely, in an example of just another historical irony, Spears’ music thrived in subsequent years when she sounded less like a girl or woman; she was most herself when she relinquished control, metamorphosed into a keyboard effect. “Toxic,” “Piece Of Me,” “Womanizer,” most of 2011’s Femme Fatale, still her most accomplished album -- so post-feminized/post-sexualized that to wonder whether she's being used by the purported figures of lust she dances with or fucks in the scripts written by male songwriters is to glance at Jamie Spears, selling a commodity to whom he allowed a fiction of home rule. She should’ve titled her third album Crossroads. Never again would her ambiguities test her and indict us.