We’re refreshing and revising our old Counting Down lists to make room for new albums and insights that have come along since their initial publication. Our first ranking of Iron Maiden's albums from worst to best originally ran on March 4, 2014.

Rivaled only by Black Sabbath and Judas Priest in regards to influence and impact on the early development of heavy metal, Iron Maiden took the burgeoning musical style to a new and very unique level -- first in the UK in the late 1970s, and soon after, all over the world. Formed in 1975 by bassist Steve Harris and gradually rising within the nascent heavy metal scene that would come to be known as the New Wave Of British Heavy Metal, the band developed a clever hybrid of gritty heavy metal that reflected their East London upbringing and a strong progressive rock tendency, with UFO and Jethro Tull serving as important signposts.

Built around twin guitar harmonies and Harris' uniquely melodic upper register basslines, Iron Maiden took the flamboyance of Judas Priest's landmark Sad Wings Of Destiny and brought in more energy, more aggression, more intricacy, which was immediately apparent on the band’s self-titled debut album in 1980. Thanks to some key lineup changes -- the additions of singer Bruce Dickinson, guitarist Adrian Smith, and drummer Nicko McBrain solidified the "classic" Maiden lineup alongside Harris and guitarist Dave Murray -- visionary management, and shrewd marketing that future metal bands would copy for decades, the band would quickly become one of the biggest acts in the genre in the mid-1980s. However, that’s only one third of a remarkable story. The 1990s would be as creatively and commercially dismal as the 1980s were successful, but the band would rebound in an astonishing way in the 2000s with a series of strong albums and groundbreaking world tours. Today, with a new generation having caught on to their timeless music, the band is more popular globally than they ever were before, one of the biggest moneymakers in the music business. They just announced what will surely be a profitable 2022 North American tour.

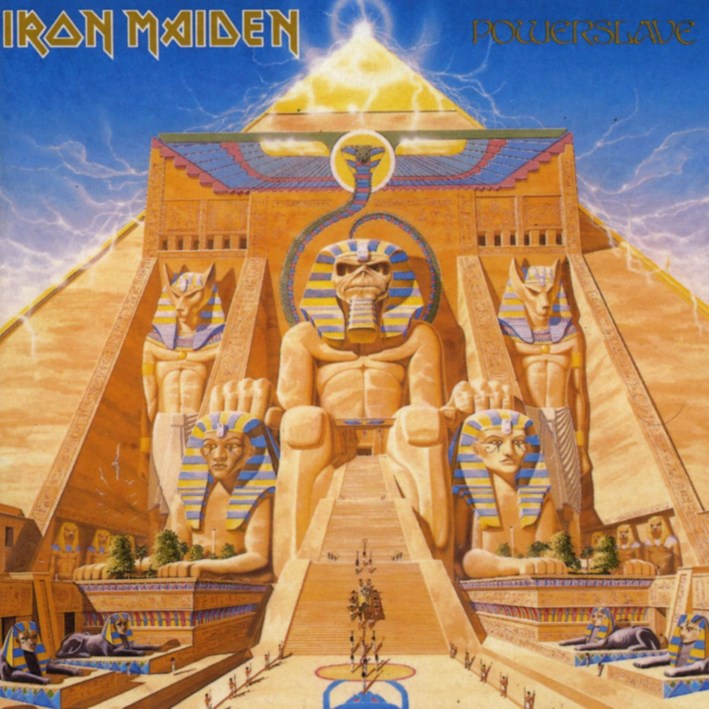

Like any other band that’s been around for well over four decades, it’s easy at first to separate the good albums from the worst, but with Maiden, ranking them quickly becomes an interesting conundrum. The fact is, as sterling as their reputation is, there is no such thing as a perfect Iron Maiden studio album. Either an album has at least one little bit of gristle or just isn't as prime a cut as others, which is why when you ask longtime Maiden fans which album is best, you'll likely get some strong differences in opinion. The fun thing about Iron Maiden is that the music means so much to people that the fans' choices of their favorite is often the first Maiden album they ever heard. For yours truly, a fan of 30 years and counting, that's Powerslave; it is my personal favorite Maiden album, hands down. But it's not their best, and the challenge of this massive list has been to remove all sentimentality and assess this band with a strictly objective critical ear.

Will certain rankings ruffle a few feathers? Knowing the passion of metal fans, most likely (sorry kids, "Fear Of The Dark" is a terrible song). But the great thing about lists like these is that they provoke discussion, and there's no better discography to dissect, celebrate, criticize, and discuss than that of the greatest heavy metal band that ever walked the earth. Okay, now that's my personal bias speaking. Enjoy.

Postscript: Because there will be some nitpicky fans that will likely demand to know why the live releases aren’t ranked in detail, here you go.

1. Live After Death (1985)

2. Rock In Rio (2002)

3. Nights Of The Dead, Legacy Of The Beast: Live In Mexico City (2020)

4. En Vivo! (2012)

5. Beast Over Hammersmith (2002)

6. Maiden England ’88 (2013)

7. Maiden Japan (1981)

8. Flight 666 (2009)

9. BBC Archives (2002)

10. The Book Of Souls: Live Chapter (2017)

11. Death On The Road (2005)

12. A Real Dead One (1993)

13. Live At Donington (1993)

14. A Real Live One (1993)

At the pace Iron Maiden were going at the end of the 1980s, it was only a matter of time before the seams started to split. Of course, those of us kids who had spent our entire teen years following the band’s ascent were so used to consistently strong work from them that we became spoiled. Maiden surely can’t mess up, can they? By 1989 Maiden had capped off an extremely grueling seven-year cycle of album/tour/album/tour, and it was clearly wearing down the band. Bruce Dickinson was itching to exercise more creative control himself, and his outlet was a pair of solo efforts, the comically awful “Bring Your Daughter…To the Slaughter” for the A Nightmare On Elm Street 5 soundtrack, and then the vibrant, joyful Tattooed Millionaire album, made in collaboration with his friend and former Gillan guitarist Janick Gers. Meanwhile, guitarist Adrian Smith, a crucial songwriting contributor, had issues with the more simplified direction Steve Harris was steering the band in, and announced his departure as the band prepared to record their eighth album in Steve Harris' home studio. Interestingly, Gers would join the band as Smith’s replacement. The end result of this tumultuous period, No Prayer For The Dying is the depressing sound of a band running on fumes and totally devoid of ideas. Martin Birch’s production is terrible, the raw sound a severe contrast from their previous albums, but that’s just the least of this album’s problems. Compared to Tattooed Millionaire, on which he sounded liberated, it feels like Dickinson doesn’t give a damn on No Prayer, as he ditches his powerful singing in favor of a cartoonish snarl. Even worse, the songs fail to deliver. Opening track “Tail Gunner” is the album’s catchiest track, but lacks firepower and comes off as a pale rip-off of Powerslave’s "Aces High." The title track is a clumsy ballad, “Mother Russia” tries to be another album-closing epic but is rigid and powerless, and “The Assassin” is simply embarrassing (“Better watch out!”). Elsewhere the band relies on beaten-to-death heavy metal clichés, like televangelist baiting (“Holy Smoke”), awkward innuendo (“Hooks In You”), and bad jokes (“Public Enema Number One”). And just when you think things couldn’t get worse, “Bring Your Daughter…To The Slaughter” is carted out, given a Maiden-friendly tweak by Harris but sounding even more awkward. In a horrible bit of irony, “Bring Your Daughter” would be Iron Maiden’s only #1 single in the UK, inexplicably topping the chart on January 5, 1991, right smack in the middle of the novelty single season. In the end it was darkly fitting, serving as confirmation that Maiden had been reduced to a joke. However, as betrayed as many fans felt, little did anyone know that No Prayer For the Dying would kick off a career nadir for Iron Maiden that would last for the rest of the 1990s.

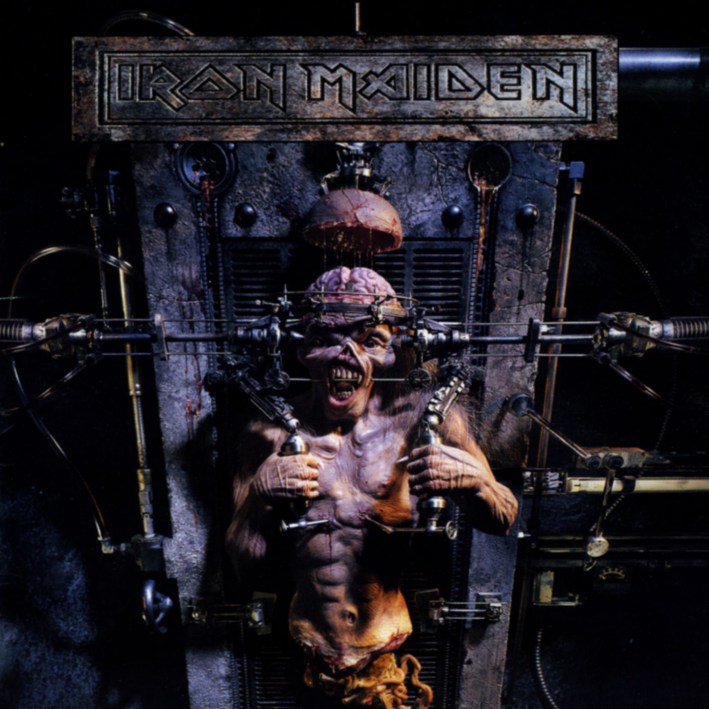

Steve Harris has always been the captain that steers the Iron Maiden ship, but he’s also a guy who thrives with good collaborators, specifically Bruce Dickinson and Adrian Smith. When left to his own devices, Maiden’s music can quickly lose focus, and that’s exactly what happened on 1998’s Virtual XI, the second, and mercifully final album of the near-unforgivable period with Blaze Bayley as singer. Fans have been notoriously hard on Bayley, who replaced Dickinson in 1994, and indeed he never could hold his own when performing Dickinson’s classic songs, but on his two albums with Maiden the melodies are more in his vocal wheelhouse. The big problem is the quality of the material he was given, or lack thereof. “The Angel And The Gambler” sees Harris channeling his inner UFO fan, but the hookless song, painfully augmented by clumsy intrusive keyboards played by Harris, carries on and on for nearly 10 minutes when three or four would have sufficed. The album’s second half is especially abysmal, a bloated slog that feels twice as long as its 27 minutes. Harris is self-plagiarizing on “The Educated Fool” and “Don’t Look To The Eyes Of A Stranger,” and “When Two Worlds Collide” and “Como Estais Amigos,” while marginal improvements, are still far too tepid and give Bayley nothing to work with. What makes Virtual XI a slight notch better than No Prayer For The Dying is that it has a pair of genuine highlights, one good, one great. “Futureal” is an energetic first track that gets the album off to a rampaging start. And don’t let naysayers tell you otherwise, “The Clansman” is a latter-day Maiden classic. The one moment where Harris’ self-indulgence yielded a moment of inspiration, the Celtic-tinged song, inspired by the films Braveheart and Rob Roy, is the kind of masterful exercise in heavy metal dynamics that was Maiden’s bread and butter during the 1980s. Bayley turns in his best vocal performance with Maiden, leading the band through the mellow intro, galloping verses, and triumphantly goofy chorus of “Freedom!” Bolstered by a tremendous solo break by Murray and Gers, it’s a bracing track, which would be proven when Dickinson, in true Dickinsonian style, would make the song his own on the Rock In Rio live album. 1998 was an ambitious year for Maiden; not only did Virtual XI come out in March, but Harris and the band were busy overseeing the development of Ed Hunter, a first-person shooter video game in the tradition of Doom, as well as the remastering and reissuing of the entire back catalog. Virtual XI was a commercial flop, however, and Bayley’s voice failed to withstand the rigors of touring, yielding some embarrassing live renditions of Maiden classics. As grim as it was at the time, hitting rock bottom sales-wise would turn out to be the best thing to happen to the band. Bayley was fired in early 1999, and not long afterwards the remaining band members would reconcile with Dickinson and Smith, be reinvented as a six-piece, and soon kick off a late-career resurgence that would see their worldwide popularity hit an all-time peak.

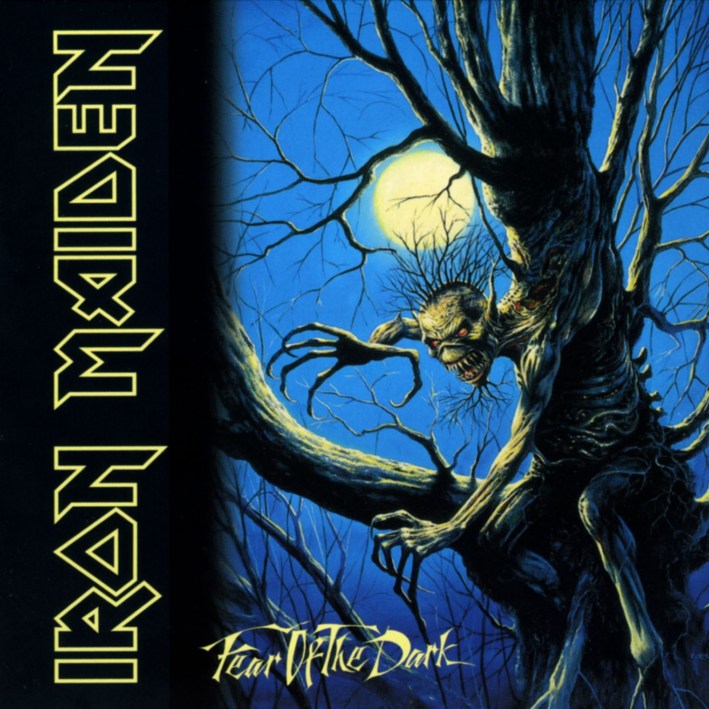

After the stagnant, uninspired No Prayer For The Dying, Iron Maiden clearly had to make a much stronger statement, and spurred by emerging progressive metal phenoms Dream Theater -- whose demos impressed Bruce Dickinson -- at first it indeed felt like the band’s ninth album would be just that. With Steve Harris credited as co-producer with Martin Birch for the first time, the sound of Fear Of The Dark was a great improvement over the previous record, and in a bold move, illustrator Melvyn Grant concocted a new version of mascot Eddie for the cover, replacing Derek Riggs, who had grown tired of drawing Eddie after Eddie for well over a decade. Opening cut “Be Quick Or Be Dead” is unusually aggressive and harsh, a propulsive, Motörhead beat-driven rager written by Dickinson and Janick Gers, with Bruce mostly using an atonal snarl. It was a departure from his usual “air raid siren” singing, but at least it was a concerted attempt to inject some life into the band’s new music. Sadly, the band fails to maintain that momentum. Attempts at hookier material fall flat (“From Here To Eternity”), as do attempts to broaden the sound (the “Kashmir” rip-off “Fear Is The Key”). Even worse, power ballad “Wasted Love”, a leftover from Dickinson’s solo writing sessions with Gers, finds the band horribly, painfully out of their element, the bridge sounding so awkward it’s embarrassing. Only do Harris’ brooding “Afraid To Shoot Strangers” -- an admittedly good live song -- and Dickinson and Dave Murray’s vastly underrated, melodic “Judas Be My Guide” manage to make any sort of impression. And then there’s the title track, this album’s biggest problem. Of course, “Fear Of The Dark” has gone on to become one of Maiden’s most enduring live staples, thanks in large part to two famous live renditions, one recorded at Donington in 1992 (and released as a video a year later) and another from Rock In Rio in 2001, during which half a million Brazilians sang along with unadulterated, contagious joy. It’s easy to see how this song works in a live setting, its intro and bridge lending itself perfectly for the soccer-style sing-alongs, and that Rio performance is chilling thanks to the fervent audience participation. However, structurally it’s one of Harris’ laziest songs, going through the motions from start to finish: mellow intro, explosive verse, galloping bridge, fast solo break, galloping chorus, mellow outro. It’s Songwriting Dynamics 101, but done in such obvious, pandering fashion that it feels beneath him. This is the guy who wrote the masterful “The Rime Of The Ancient Mariner,” for crying out loud. And those lyrics: “Fear of the dark, fear of the dark, I have constant fear that something's always near.” For fuck’s sake, Steve. It was a moment where a band best known for being uncompromising instead pandered to their audience. Of course, the dumbest song often turns into commercial gold -- look at the UK chart-topping idiocy of “Bring Your Daughter…To The Slaughter” -- and mass audiences gravitated toward the track immediately. Dickinson, whose lack of interest in the band was getting more and more obvious -- he’d started touring as a solo artist and looked apathetic onstage with Maiden -- would do one final farewell tour in 1993 and announce his departure, leaving Harris and Iron Maiden with the impossible task of replacing one of metal’s most charismatic and popular frontmen.

Wait, what? The X Factor, the album that kicked off the dismal Blaze Bayley years and sent Iron Maiden spiraling downward to its nadir, is not only just the fourth worst album in the entire catalog, but is ranked higher than two Bruce Dickinson albums? With all confidence, yes. Granted, it’s like choosing the best method of torture; it’s the best of a very sorry quartet of albums. Left to pick up the pieces after Dickinson’s departure in 1993, Harris hired Blaze Bayley, a singer best known for fronting a likable band called Wolfsbane, whose debut album of no-frills barroom heavy metal was produced by none other than Rick Rubin. It was an impossible situation; Dickinson left a void so huge that there was no way the band could possibly rebound successfully. But Maiden was and still is Harris’ baby, and whether he was out to stubbornly keep the brand alive or just show up Dickinson -- a little of both, most likely -- he had something to prove. Not only was Dickinson gone, but legendary producer and longtime collaborator Martin Birch retired, and Harris decided to team up with Nigel Green as co-producer. Compounded by his own personal problems at the time -- divorce and the death of his father -- the songs on The X Factor were very dark in theme, which was reflected in the overall tone of the record. In addition, Hugh Syme’s disturbing digital illustration of a mutilated Eddie on the cover served notice that not only would this be a very grim album, but also fans would have to get used to this new, reinvented version of Iron Maiden. Songwriting-wise, The X Factor is very much on the same level of Fear Of The Dark, driven by a self-plagiarizing Harris, the low register of Bayley’s voice adding to the murky mood. “Fortunes Of War” and “The Edge Of Darkness,” while following that now-familiar Harris template -- slow build-up to a climactic gallop -- are nevertheless good, surprisingly brooding exercises in Maiden predictability. “Lord Of The Flies,” one of the band’s most spirited songs of the 1990s and one of Gers’s best songwriting efforts, is reminiscent of the lively material the band came up with a decade earlier (Dickinson would breathe life into the track on 2005’s Death On The Road live album). Inspired by the film Falling Down, “Man On The Edge” is a terrific speedster that would have served as a good opening track for the album, but Harris had other, crazier ideas. It takes a lot of hubris for a popular band to kick off its most controversial album with an 11-minute song, and in retrospect it was the wrong move, as Harris was daring fans to accept the changes in the band to the point of alienating them. But nearly 20 years after its release, “Sign Of The Cross” is a tragically underrated Maiden classic. Compared to the amateurishness of the godawful yet popular “Fear Of The Dark,” “Sign Of The Cross,” inspired by Umberto Eco’s The Name Of The Rose, has Harris sounding his most daring since the Powerslave days, creating a complex yet memorable and theatrical epic. Moody and murky, and featuring challenging tempos anchored by the ever-reliable drummer Nicko McBrain, Bayley turns in a good vocal performance as the song ebbs and flows, building to a tremendous bridge and solo break. Like Virtual XI’s “The Clansman,” “Sign Of The Cross” would prove its worth with Dickinson at the helm on Rock In Rio. Of course, while Bayley merely put in workmanlike performances on those tracks, Dickinson would come along and completely own them, and therein lies the problem with not only the two Blaze albums, but with No Prayer For The Dying and Fear Of The Dark as well: Dickinson’s charisma is every bit as important to Iron Maiden as his vocal skill, and on those four records, it went missing, which is why there is a veritable gulf separating Maiden’s four worst and 11 best albums.

That cover. That cover. For a band enjoying its biggest global success since 1988, with a fan base eagerly awaiting the follow-up to a comeback album for the ages, and with a reputation for some of the most indelible cover art in heavy metal history, the cover for Iron Maiden’s 13th album could not have been more underwhelming. An amateurish, computer-generated attempt at placing Eddie in the middle of an Eyes Wide Shut-inspired fever dream, the image adorning Dance Of Death is a complete mess: characters with comically contorted necks and limbs, an infant awkwardly sitting on a dog that’s awkwardly standing on a snake. It’s all too much. As the story goes, the band decided to go with artist David Patchett’s “unfinished prototype” instead of his completed work, and Patchett subsequently demanded his name be removed from the album credits. It was not a good way to kick off a marketing campaign, and once listeners got beyond that awful artwork, the actual music inside turned out to be almost as curious, but thankfully not as sloppy. At 68 minutes, it’s one of the band’s longest albums, and arguably the most self-indulgent. There’s a handful of songs that fit neatly into that Iron Maiden template, from the energetic opener (“Wildest Dreams”), the hooky single (“Rainmaker”), and the requisite Harris epics (“No More Lies,” “Dance Of Death”), all of which are indeed by the book, yet strong. However, the real charm of Dance Of Death can be found the deeper into it you go. The raging “Montségur” is an inspired piece, the heaviest song the band recorded in the 2000s. “New Frontier” and “Gates Of Tomorrow,” the latter featuring Nicko McBrain’s first ever songwriting credit, are vibrant tunes, bolstered by Dickinson’s strongly sung choruses. “Journeyman” is a good little curveball, an acoustic number whose subtlety offers a welcome counterpoint to all the bombast. The kicker, though, is Adrian Smith’s masterful “Paschendale,” an eight and a half-minute portrait of World War I trench warfare, written with cinematic flair and sung with gusto by Dickinson. Slightly too long for its own good -- two or three songs could have easily been excised -- Dance Of Death was a small step down from 2001’s Brave New World, but was nevertheless a sign that the band was enjoying its creative rebirth. The next two albums would turn out to be even better, and even more encouraging, the artwork for each would be massive improvements.

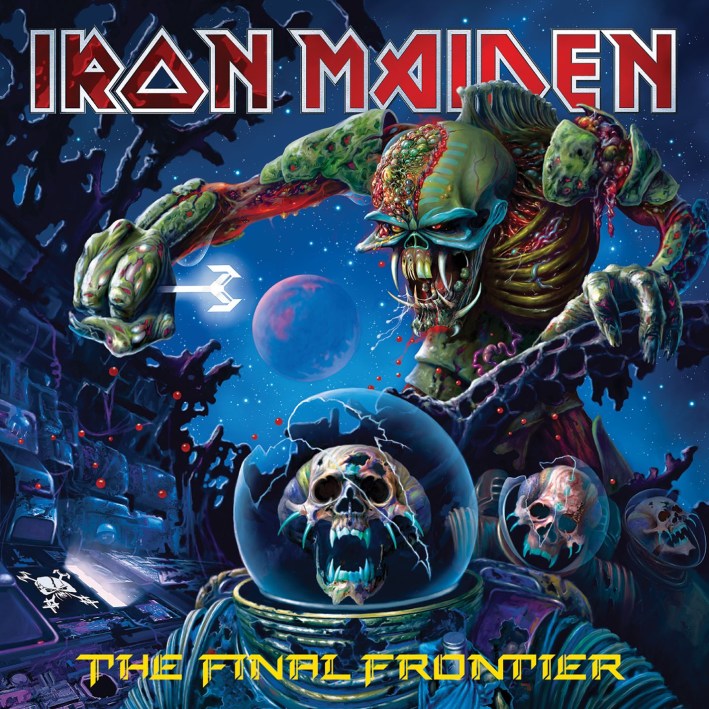

Thirty years after the release of their debut album, you could easily excuse a band like Iron Maiden for coasting a little if they wanted, riding off into the sunset with an album or two that stuck to the formula and respectfully played it safe. Instead, invigorated by a triumphant, decade-long resurgence and a forward-thinking approach to touring the world, these old codgers came out with a startlingly ambitious album in 2010. Loaded with songs in the seven to 11-minute range, the band’s post-reunion progressive bent is at its zenith, but at the same time there’s an attention to detail in the melodies, making for an invigorating, incessantly catchy record. Settling into more of a role of principal arranger than chief songwriter, Steve Harris has opened himself up to more ideas from his bandmates, and the 10 songs sound remarkably fresh as a result. Adrian Smith is especially prominent on this record, coming through with some of his best work in years, most noticeable on the audacious opening track “Satellite 15… The Final Frontier,” which sees a surreal, almost tribal intro of noise and percussion segue into an explosive tune reminiscent of UFO. “El Dorado” utilizes the classic Maiden gallop with a sense of renewed verve, “Mother Of Mercy” carries itself with stately grace, the ballad “Coming Home” succeeds in every way that “Wasting Love” failed 18 years earlier, while “Isle Of Avalon” and “Starblind” are vibrant, their long running times feeling natural rather than forced. Elsewhere, Janick Gers comes through with his best songwriting contribution to date with the propulsive “The Talisman,” while Harris’ one solo composition “When The Wild Wind Blows” shows incredible subtlety, successfully bringing some gravitas to an undeniably grandiloquent album. Compared to the stubbornly unmastered sound of A Matter Of Life And Death, producer Kevin Shirley brings a little more color and depth to The Final Frontier, which in turn gives Bruce Dickinson more room to showcase his vocal power. While not a seminal work like Maiden’s five best albums, it continues a remarkable creative run that would continue through 2021.

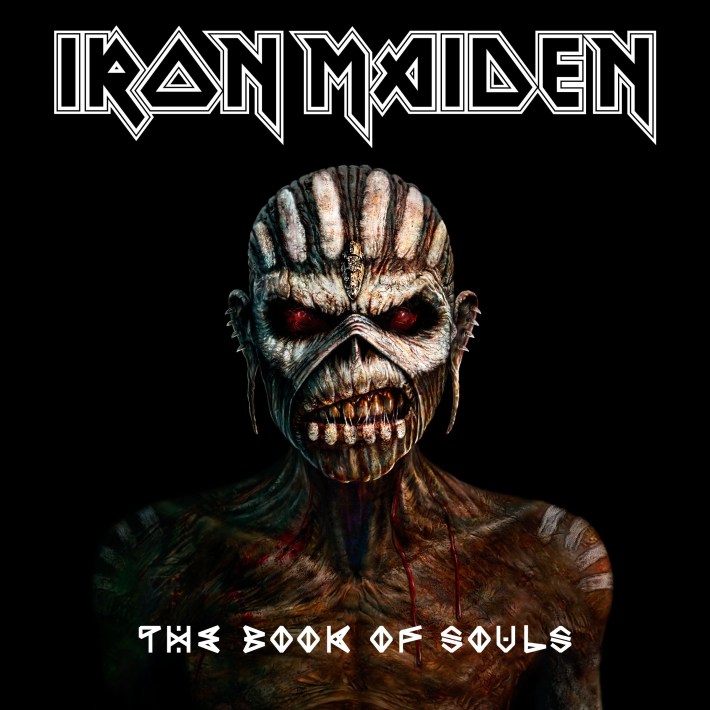

Iron Maiden’s steady post-millennial evolution reached a pivotal moment in 2015. The band had been broadening their songwriting style more and more since 2000’s Brave New World, combining their classic 1980s sound with a much more progressive angle, and The Book Of Souls saw the sextet throw themselves headlong into that prog side even more. The result was a wildly ambitious, 92-minute double album that takes risk after risk only to come out invigorating, fresh, and, for the most part, triumphant. A big reason The Book Of Souls works so well is its pacing. True, the bulk of the record ranges from long tracks to even longer tracks, but interspersed among all the epic compositions are shorter, anthemic, accessible songs that hearken back to Maiden’s classic era. Adrian Smith is usually behind the band’s grooviest, most immediate tracks, and single “Speed Of Light” is a prime example, built around a rollicking lead riff propelled by a swift, four-on-the-floor beat by Nicko McBrain. A big crowd favorite on the subsequent world tour, “Death Or Glory” sees Smith and Bruce Dickinson returning to the aerial dogfight theme of “Aces High,” but instead of the blazing speed of that classic song “Death Or Glory” possesses a mighty swing that adds gravitas to a viscerally exhilarating song. Smith partners with Steve Harris on the somber “Tears Of A Clown,” and hokey title aside the track turns out to be a surprisingly affecting portrait of manic depression, directly inspired by the death of Robin Williams. Not every track works as well -- “When The River Runs Deep” and “Shadows Of The Valley” would not be missed if they were excised -- but the album’s best epics overshadow those slight bumps. Harris, as is his predilection, is all over many of those tracks. While the pacing of “The Red And The Black” is predictable for anyone familiar with the bassist’s writing style, the hooks are rousing -- those “whoa-oh”s helped the song become a setlist staple -- and Dickinson sells the hell out of the lyrics, making for a bracing piece of progressive metal theater. The title track, meanwhile, explores the Mayan culture, namely the idea that souls continue living long after the body dies. Dickinson is in spectacular form, shifting from dramatic lower-register verses to his trademark soaring high notes in the chorus, while Harris leads his troops through a wickedly exciting, extended coda peppered with triplet riffs reminiscent of “Rime Of The Ancient Mariner.” The album’s two finest moments, not to mention the most experimental, are solo compositions by Dickinson, interestingly enough. Originally intended for a possible solo concept album, “If Eternity Should Fail” caught the attention of Harris, who insisted the track was too damned good to not be given the Maiden treatment. Kicking the album off in grand fashion, Dickinson belts out two intro verses accompanied by synth, and when the full band joins in the song kicks off into a stately gallop that doesn’t let up for six minutes. Comically, the “Doctor Necropolis” mentioned in the outro narration was originally a character intended for Dickinson’s album, but Harris essentially said, “Screw it, it fits the album thematically.” And it does! Nothing on the entire album, however, prepares the listener for the final song. At 18 minutes, “Empire Of The Clouds” is Maiden’s longest recorded track, but most importantly, it’s easily the band’s most ambitious, all springing from the imagination of their singer. A perpetual student of aviation history, Dickinson was inspired to write about the 1930 R101 disaster, when the British airship crashed in France on its maiden voyage, claiming 48 lives. Starting off as a classical piano-driven ballad, Dickinson paints a vivid portrait ("Groundlings cheered in wonder/ As she backed off from the mast/ Baptizing them her water from the ballast fore and aft") as the song moves gracefully from pastoral moods to slowly increasing tension. McBrain is the hero of this track, his expressive drumming in the song’s first third shifting into the jarring syncopation of the “SOS” Morse code, which initiates an extraordinary eight-minute instrumental section during which McBrain, Harris, Smith, Dave Murray, and Janick Gers flex their collective muscle, trading solos, changing tempos. For a band to be this inventive this late in their career is a marvel, and “Empire Of The Clouds” caps off a tremendous album in stirring fashion.

After the jubilance of Brave New World and Dance Of Death’s assertion that the comeback was no fluke, Iron Maiden returned in 2006 with an album that showed renewed focus and passion. Although it clocked in at a whopping 72 minutes, A Matter Of Life And Death was Maiden’s most musically and thematically consistent album since 1988’s Seventh Son Of A Seventh Son, as the band tacked mortality, war, and the overall state of the world with surprising gravity. From the songwriting to the production, it’s quite extraordinary how understated this album is. Kevin Shirley and Steve Harris decided not to master the album at all, choosing to give listeners the purest sound of the band on record rather than going for the usual metal trickery of compression and quantizing. The final result rubbed some listeners the wrong way because it didn’t sound like every other metal album out there, but that was precisely the point. Refusing to rest on their laurels, the band was daring to try something a little different, and daring their fans to come along for the ride. After the rote opening track “Different World,” which is basically a rehash of Dance Of Death’s “Wildest Dreams” and a bit of a red herring, the album quickly gets down to serious business with a remarkable series of songs that eschew bombast for subtlety, hooks for heaviness, and gimmickry for honesty. “These Colours Don’t Run.” “Brighter Than A Thousand Suns,” “The Pilgrim,” “The Longest Day,” and “Out Of The Shadows” carry themselves with dignity, the band in total command. It’s an incredibly democratic record, too, feeling like a true collaboration rather than Harris leading the way with the odd bandmate chipping in. As a result his penchant for self-plagiarizing is kept at bay, reflected in the way these songs flow so well. The heartfelt and powerful epic “For The Greater Good Of God” and the stately “The Legacy” bring the album to a wonderful conclusion, but the real highlight on A Matter Of Life And Death is the enigmatic, quirky “The Reincarnation Of Benjamin Breeg.” The best encapsulation of the album’s powerful yet meditative quality, the track is built around a simple yet unusually muscular riff, with Harris keeping his usually dominant, upper-register basslines on the lower end of the scale. Dickinson, meanwhile, is more controlled in his singing that he ever was on any Maiden record in the past, and “Benjamin Breeg” and “For The Greater Good Of God” are his most masterful moments. The band was so justifiably proud of A Matter Of Life And Death that they performed the album in its entirety on the subsequent world tour. Leaving room for only five older songs, it was an audacious move, but in the end it worked, lending great credibility to the band, who steadfastly refused to turn themselves into an oldies act, and it helped connect them with a new generation, a much younger crowd than those who grew up with their music in the 1980s. It was a cunning move that would set the stage for a remarkable run, as the massive Somewhere Back In Time tour in 2008 and 2009 would see Iron Maiden’s worldwide success reach an all-time high.

After a lost decade Maiden returned not only reunited, with Bruce Dickinson and Adrian Smith back in the fold, but expanded to a six-piece as well, retaining Janick Gers as third guitarist, and the positive momentum from the band’s modest Ed Hunter reunion tour carried over into their 12th album. In fact, so spirited and inspired is Brave New World that upon first listen it felt as if the previous dozen years hadn’t even happened. Brave New World isn’t so much a reinvention of Iron Maiden as a simple righting of the ship, the band sticking to their strengths, simplifying their approach, and having all songwriters make valuable contributions. “Ghost Of The Navigator,” “Brave New World,” and “Dream Of Mirrors” have the sextet firing on all cylinders, achieving the effortless balance of melody, power, and epic scope that the band failed to pull off consistently in the 1990s. “The Mercenary” is a wonderful reference to the band’s early sound, while the acoustic-tinged “Blood Brothers” and richly layered “Out Of The Silent Planet” experiment a little, anticipating a decade that would see the band making bolder and bolder songwriting choices. All the while, Dickinson, who was dearly missed by fans, is in commanding form, benefiting greatly from a decade of less rigorous touring and a more concerted effort to improve his live singing. Although Smith’s contributions to this album are minimal, he proves just how valuable a songwriter he is on the explosive opening track “The Wicker Man.” Built around his simple yet contagious palm-muted lead riff and featuring a rousing chorus and a made-for-stadiums sing-along coda, it’s the most exuberantly catchy Iron Maiden song since 1988’s “The Clairvoyant,” and most importantly, the kind of statement that longtime fans had been dying to hear for so many years. Maiden were back, with their true frontman back at the helm, and they were in prime form. The popularity of “The Wicker Man,” Brave New World, and the spectacular live album Rock In Rio two years later would kick into gear a period of unprecedented global success for the band, which continues to this day.

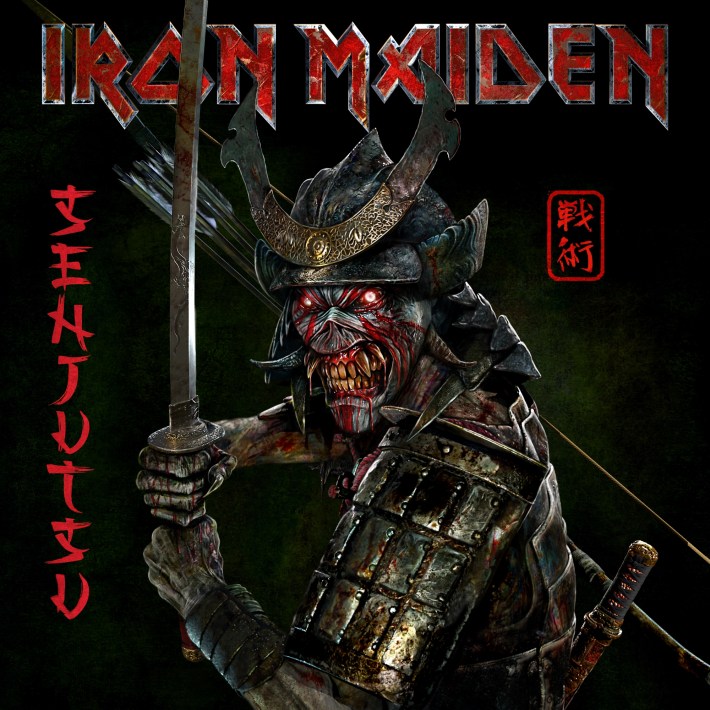

When well-regarded musical artists transition from their “imperial” phase into their “legacy” phase, all their fans require of any new music is that it holds up decently against their older classic work. Just don’t embarrass yourself is all we ask of our aging musical heroes. The last thing anyone expects from a band approaching the completion of their fifth decade is a latter-day classic, but that’s what Iron Maiden pulled off in 2021, doubling down on the double album idea of 2015’s The Book Of Souls and releasing a similarly long follow-up that’s denser, more challenging, and even better than its predecessor. Recorded in late 2019 and shelved for nearly two years because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Senjutsu is a colossus that requires time to wriggle into the listeners’ consciousness. Lots of time. Aside from a couple shorter tracks, it feels mighty unwieldy at first, with epic track after epic track unfolding steadily, one after the other. On a personal note, it took yours truly at least two months to even start to admit to myself, “Wait a minute, this thing is even better than my cautious initial assessment.” Some songs on this 82-minute, 10-track album are better than others, but there’s not a throwaway among them. When it was revealed that the bulk of Senjutsu was written by Steve Harris, alarm bells went off in the minds of many. Harris is a beloved individual, the one who guides Iron Maiden’s vision, but he can be a predictable songwriter, especially when he takes over an entire album. Savvy listeners can predict the next movement well before it happens, and the usual signposts are noticeable throughout Senjutsu. Here’s the kicker, though: The songs are so damned good that Harris’ predictability hardly matters. These are some of the best songs he’s written in years, and the entire band is on fire, ceding to Harris’ vision and sounding incredible throughout. The first half of the record serves up some excellent variety. The thunderous title track is the heaviest thing Iron Maiden have ever recorded, producer Kevin Shirley putting bass and drums right up front, mixing the three guitars into a thick morass that almost sounds mono. Dickinson, more than four years after beating throat cancer, shows signs of age in his voice but adapts in impressive fashion, a hint of wizened, weathered grace in his singing. The rousing “Stratego” is the catchiest song Maiden has recorded since “Rainmaker” in 2003 and Adrian Smith shines on his English folk-derived “The Writing On The Wall,” while “The Time Machine” combines playfulness and somberness in a way that only a veteran band can execute. As strong as those first 40 minutes are, it’s all in preparation for the four towering epics in store. Smith and Dickinson team up for the melancholy yet mighty “Darkest Hour,” a stirring depiction of the turning point of Winston Churchill’s World War II leadership. After that it’s the Steve Harris Show, in which he writes a great track, then outdoes himself, then outdoes himself again. It’s easy to dismiss “The Death Of The Celts” as a carbon copy of 1995’s classic “The Clansman” -- and there are indeed similarities -- but there’s a mournfulness to this song that sets it apart, less chest-beating Braveheart shtick and more of an acknowledgement of a culture’s last stand. Reminiscent of 1984’s “Powerslave,” “The Parchment” cranks up the darkness and drama, its “Kashmir”-inspired, processional riff creating a hypnotic effect as Dickinson leads a slow crescendo that explodes into a spectacular sustained note in the final verse and sends goosebumps shooting up the listener’s spine. Segueing from the scintillating to the sublime, “Hell On Earth” feels like Harris’ most personal song to date. Led by a gentle melodic motif that reprises throughout the 11-minute song, Harris lays bare his concerns for humanity, which in turn is conveyed in beautiful fashion by Dickinson. The invigorating gallop of the track is a red herring, though, as this is one desperately sad song, Harris writing, “When I leave this world I hope to see you all again/ On the other side of hell on earth.” The only thing we can do is to keep plugging away and try to keep doing our best in life. Harris and Iron Maiden clearly take that thought to heart on the supreme Senjutsu, hitting a new peak in a career filled with many.

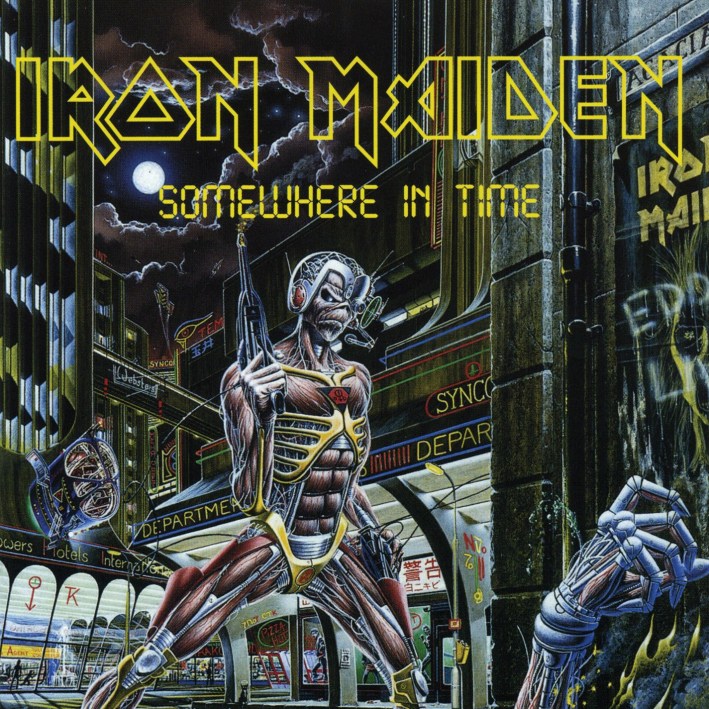

1986 was going to be all about Slayer and Metallica. Metal fans knew it going into that year, and no doubt bands did as well. Heavy metal was advancing at an exponential rate, and every couple months -- and at times even every few weeks -- an album came out that pushed the still-nascent genre’s creative boundaries further outward. The already established veteran bands couldn’t help but feel the pressure, and their albums that year hinted at a bit of an identity crisis among them, as they pulled out all the stops to sound as cutting edge as possible. Iron Maiden and their countrymen Judas Priest became enamored of a particular gimmick that year, the guitar synthesizer, and both created albums built around that instrument. Both albums sold very well, but it was Maiden’s Somewhere In Time that maintained a sense of integrity rather that feeling like a gimmick. Indeed, the follow-up to 1984’s wildly successful Powerslave opens on an audacious note, the blend of guitar and synthesizer flying right in the face of the perceived prerequisite that all heavy metal be guitar-based and nothing but. What the band does throughout the album, however, is use the synths as window dressing rather than the focal point. All but one song utilizes guitar synths, but only for atmospheric purposes, a good complement to the Blade Runner theme running through the title track and Derek Riggs’ spectacularly intricate gatefold artwork. As a result, there’s a graceful quality to the album’s best songs, in which power, melody, and ambiance coalesce into a cohesive whole. The title track, “Sea Of Madness,” “Heaven Can Wait,” and “Stranger In A Strange Land” are all prime examples of an established band benefitting from a little experimentation. That said, Somewhere In Time is a curiously inconsistent album -- “The Loneliness Of The Long Distance Runner” and “Déjà Vu” both stumble -- and in retrospect is a perfect reflection of the internal strains within the band. After such a rigorous pace -- three albums and three gigantic world tours in three years -- the band was still burned out after taking much of 1985 off, and even worse, was at odds regarding how the next album should sound. Such was the creative divide between Bruce Dickinson and Steve Harris that Dickinson’s songwriting contributions were all rejected, but despite the merit of Harris’ “Heaven Can Wait” and “Caught Somewhere In Time,” this album will forever be remembered as the Maiden album Adrian Smith singlehandedly saved. Amidst the squabbling, he brought in several fully formed songs greatly outshining everything else on the record. “Sea Of Madness” and “Stranger In A Strange Land” display his knack for melody and dynamics, contrasting heaviness and hooks brilliantly. It’s “Wasted Years,” though, that is far and away the highlight, a catchy little travelogue that’s become one of the band’s most enduring and treasured songs. Built around a clever arpeggiated lick, an affable chorus, and Smith’s sentimental lyrics, it’s a welcome dose of soul amidst all the bombast. When I interviewed the band in 2010, I got to ask a question I’d always wanted to ask: What’s the one song they’ve never played but always wanted to play? Steve Harris and Dave Murray wasted no time in replying, “Alexander The Great.” A verbose storytelling epic in the vein of “Rime Of The Ancient Mariner” and “To Tame A Land,” it’s not a classic Maiden song by any stretch, but is nevertheless a clever one, striking a good balance between bluntness and subtlety, its mid-song instrumental break displaying a cinematic quality, and the latter half of the eight-minute song is one of Harris’s most underrated moments as a songwriter. Flaws and all, audiences were starved for new Maiden material in the fall of 1986, and Somewhere In Time sold exceptionally well, cracking the top five in the UK. The road beckoned once again, and sporting a garish, cutting edge stage show inspired by Riggs’ artwork, the band launched another grueling run of 151 shows in eight months across North America, Europe, and Japan.

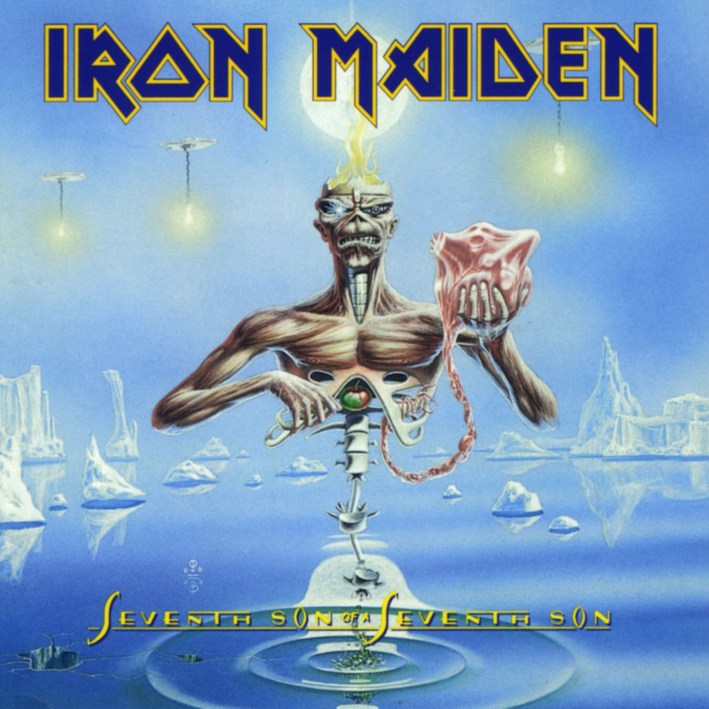

If you ask me to name the one Iron Maiden album where I find the least fault from track to track, start to finish, it’d be Seventh Son Of A Seventh Son. It’s not their most definitive album, but it’s a confident, consistent one, a snapshot of the band firing on all cylinders, in prime form during their peak in the 1980s. In the wake of the ambitious -- at times overly so -- Somewhere In Time, Maiden returned a lot more focused in the spring of 1988, sporting a concept album inspired by Orson Scott Card’s novel Seventh Son. Unlike the previous record, all principal songwriters were on board, with Bruce Dickinson an active participant for the first time since 1984’s Powerslave. With a clear mindset -- even Derek Riggs’ cover painting is a lot calmer to the eye than the chaotic album art two years earlier -- a focused approach, and a theme that everyone was able to get behind, it revisits some of the musical ideas Somewhere In Time explored, but does so with a lot more grace and consistency. Although there are not any bracing tracks in the tradition of “The Trooper,” “Run To The Hills,” or “2 Minutes To Midnight.” Seventh Son simply motors along confidently. Steve Harris chips in three of his best solo compositions in the wonderfully textured and progressive-minded “Infinite Dreams,” the stomping “The Clairvoyant” -- which boasts one of the greatest Maiden “gallops” this side of “The Trooper” -- and the scintillating title track, which continues where epics “Phantom Of The Opera,” “Hallowed Be Thy Name,” and “Rime Of The Ancient Mariner” left off. Dickinson and Adrian Smith collaborate on the mystical opening track “Moonchild,” and the three combine on the permanent live staple “The Evil That Men Do” and the curiously poppy “Can I Play With Madness?,” which would actually hit number three on the UK singles chart. Meanwhile, Dickinson’s singing on “Seventh Son” is especially noteworthy, as he turns in one of his most nuanced and commanding vocal performances of his career. Most Maiden fans like to make a lot out of the lyrical concept of Seventh Son, but personally the story has always felt too vague to have much of a visceral impact. In the end, though, what’s most interesting about this album is that its emotional punch is felt in the music, not the lyrics. The plot might be frustratingly ambiguous at times, but because the songwriting follows that story arc, the music does as well, and you feel that more. As a result, the way the album flows from song to song is remarkable. The positive momentum of Seventh Son would only last so long, cresting with another triumphant world tour in 1988 before the internal turmoil would start to kick in. Smith would surprise fans in 1990 by announcing his departure from the band during pre-production for the next album. Unbeknownst to fans at the time, the salad days were over, as Iron Maiden would go through a decline in creativity and ultimately popularity, which they would not fully regain for another decade.

Every classic band has its own transitional album, and Killers represents the moment Iron Maiden started to make that shift from gutter-level Cockney heavy metal to full-on stadium-level conquerors. The first step was to beef up the band’s sound on record, and producer Martin Birch -- fresh off of working on Whitesnake’s Ready An’ Willing, Black Sabbath’s Heaven And Hell, and Blue Öyster Cult’s Cultosaurus Erectus -- was brought on to helm the second album, marking the beginning of a partnership that would last for the next decade. In addition, guitarist Dennis Stratton was replaced by Adrian Smith, formerly of London band Urchin. Because it’s nestled between two popular and well loved albums, Killers, despite its iconic Derek Riggs artwork and all the love it gets from older Maiden fans, doesn’t attract quite the same amount of accolades, and it’s easy to see why. Steve Harris’ backlog of early songs was still strong enough that they justified inclusion on album number two, having been longtime live staples and well known by the band’s British fanbase. However, there’s the unavoidable feeling that Killers comprises leftovers, even though most are anything but. In fact, the band had so honed its sound by 1981, had become so tight, that those nine live favorites practically leap off this record. Two songs in particular highlight Killers, and are universally regarded as milestones in the band’s history. Originally released on the NWOBHM compilation Metal For Muthas in 1980, “Wrathchild” is given a complete overhaul on Killers, with the rhythm section of Harris and drummer Clive Burr churning away with force, Dave Murray delivering screaming leads throughout the song, and Paul Di’Anno in full street thug mode and leading the charge with his menacing, confrontational persona. The title track, meanwhile, takes Iron Maiden’s “Prowler” to a much more theatrical level, highlighted by that haunting, dare I say -- because Harris never would -- gothic intro that explodes into the song’s ferociously-picked verse, and featuring a sublime twin harmony section that foreshadows the formidable duo Murray and Smith that would become a hallmark of the band. Elsewhere, “Another Life,” “Innocent Exile,” “Purgatory,” “Twilight Zone,” and “Drifter” sound ferocious under Birch’s guidance, although all five are just a cut below the standards of such early Maiden favorites as “Wrathchild,” “Killers,” “Prowler,” and “Phantom Of The Opera.” And although Di’Anno is in as good vocal form as he would ever be on record, you can sense the band starting to outgrow its lead singer, especially on the two new tracks Harris wrote for the album. Much more intricate, multifaceted, brisk, and verbose than any Maiden song prior, “Murders In The Rue Morgue” nearly leaves Di’Anno in its wake as the singer does his best to enunciate those difficult lyrics and carry that quirky melody. On the other side of the coin, Di’Anno feels out of place handling the shameless progressive rock of the mellow “Prodigal Son”; although he puts in a yeoman’s effort, his singing lacks the expressiveness and range the composition requires. It would be Di’Anno’s offstage behavior, however, that would serve as the catalyst for his firing at the end of the band’s tour in support of Killers. Samson singer Bruce Dickinson would be hired in September 1981, work would commence on Iron Maiden’s third album, and the rest, as they say, is heavy metal history.

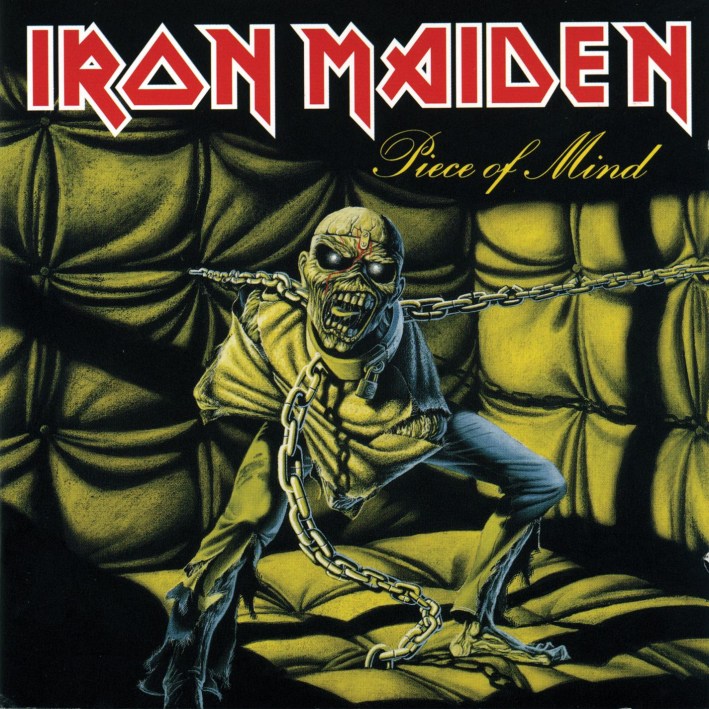

After drummer Clive Burr left Iron Maiden in December 1982, he was quickly replaced by one Michael Henry McBrain, more commonly known as Nicko, who had played with Streetwalkers and Pat Travers in the late ‘70s and, most recently, French metal band Trust. A formidable percussionist with a wickedly fast right foot and a quirky, inimitable style, McBrain makes his mark immediately on Maiden’s great fourth album, kicking off opening track “Where Eagles Dare” with an impeccable, fluid series of tom fills that echo the sound of machine gun fire, perfectly suited for the World War II-themed composition. Similar to how Bruce Dickinson revitalized the band in 1982, the gregarious McBrain tightened up the core of Maiden’s sound a year later, a perfect and equally versatile rhythm section partner for Harris, and if that wasn’t enough, a real character as well. Eager to capitalize on the resounding success of The Number Of The Beast, the band headed right back into the studio with Martin Birch in January 1983, settling in at Compass Point Studios in the Bahamas, specifically chosen to avoid the tax man back home. Recorded under the working title Food For Thought, the more cleverly renamed Piece Of Mind sees the band brimming with energy, fueled by the knowledge that global success was but one step away. The opportunity was there, and they seized upon it. What separates Piece Of Mind from every other Maiden album is that it boasts the single best run of six songs in the entire discography. Harris’ “Where Eagles Dare” is a bracing opener whose seemingly impossible vocal melody is delivered with astonishing power by Bruce Dickinson. Dickinson’s Crowley-influenced “Revelations” is refreshingly measured in pace, a progressive mini-epic that has Dave Murray and Adrian Smith adding tremendous color with their twin leads. The hooky first single “Flight Of Icarus” is the first collaboration between Dickinson and Smith, its focus on restraint and melody soon to become a Smith trademark. “Die With Your Boots On” is as close to a romp as Maiden would ever get, playful UFO-style riffing and a lively groove by McBrain carrying the entire song. “The Trooper” was an instant classic, Harris’ retelling of Lord Cardigan’s Charge Of The Light Brigade in the Crimean War the most perfect example of the Maiden “gallop” and one of the most popular songs among fans. Introduced by a backwards-tracked McBrain poking fun at American fundamentalists (“What ho said the t'ing with the three 'bonce,' do not meddle with things you don't understand,” itself a reference to the 1975 comedy album The Collected Broadcasts Of Idi Amin) “Still Life” is one of Harris’ most ambitious songs, and one of his very best. Moody and brooding, the surreal, dreamlike tale is accentuated beautifully by fluid playing by Murray and Smith and taut, tense playing by Harris and McBrain. If there’s a flaw on Piece Of Mind, it’s that the rest of Side Two fails to measure up to the first two thirds. The album’s one egregious mistake, “Quest For Fire,” is inspired by the 1981 film of the same name, and is marred by Dickinson’s outlandish vocal melody (“In a time when dinosaurs walked the earth/ When the land was swamp and CAVES WERE HOME!”) and a very clunky chorus. “Sun And Steel” is a marginal improvement, the Smith/Dickinson partnership again yielding a strong chorus hook despite the awkward rhyming scheme, while Harris’ “To Tame A Land” attempts to condense Frank Herbert’s novel Dune into seven and a half minutes only to fall short of the mark. It’s a solid effort, but Harris would perfect that CliffsNotes heavy metal epic idea on the following album. The band would hit the road from late April through December, touring North America and Europe extensively, with the success of “Flight Of Icarus” and “The Trooper” propelling the band to new heights of popularity. As good as things seemed, Iron Maiden’s fortunes would improve even more, literally and figuratively, in 1984.

Iron Maiden’s fifth album arrived at just the right time. 1984 was a perfect storm for heavy metal: Its popularity was surging, music videos were bringing the genre to millions of young people, and the new teen generation was consuming music at an unprecedented rate, creating a dazzling and diverse array of superstars. The zeitgeist was primed for Maiden to capitalize, and they did just that with an ambitious, relentlessly catchy, and scorching album that would see their global popularity explode. Recorded in early 1984, once again with Martin Birch at the helm and for the second consecutive year at Compass Point in the Bahamas, Powerslave might not be Iron Maiden’s absolute artistic pinnacle, but it comes awfully close. The band knew they were on the cusp of something gigantic, and they went big, reflected in Derek Riggs’ gorgeous, grandiose, and intricately detailed Egyptian-themed artwork. Fresh, vibrant, and brimming with energy, the music inside was bracing and triumphant. Songwriting-wise, the band swings for the fences on Powerslave, and 32 of its 50 minutes consist of the best work the band would ever do, its high points so strong that the lesser moments are easy to forgive. Admittedly, the instrumental “Losfer Words (Big ‘Orra)” is a complete toss-off, an unnecessary momentum killer three tracks in, but the three other mid-album tracks, which have never been performed live by the band, more than hold their own. “Flash Of The Blade,” a solo composition written by the fencing-obsessed Bruce Dickinson, is a brisk little number bolstered with a lively chorus hook and a whimsical neoclassical bridge. Steve Harris has a little fun with the swordplay theme with the more stately “The Duellists”; typical of his songwriting, he gives Dickinson a colossal challenge with his overly wordy lyrics and seemingly impossible vocal melody, but Dickinson, in classic form on this album, pulls it off with aplomb and verve. Written by Dickinson and Adrian Smith, “Back In The Village” is the most underrated Iron Maiden song of all time, a searing sequel to 1982’s “The Prisoner” that revisits the great Patrick McGoohan TV series and boasts a very nimble lead riff by Smith. However, the four songs that comprise the core of Powerslave are something special. “Aces High” is the definitive Maiden album (and concert) opener, Harris’ explosive, thrilling depiction of the Battle Of Britain from a fighter pilot’s perspective delivered at breakneck speed, peppered with brilliantly timed divebombs, featuring the best guitar interplay between Smith and Dave Murray on record, and dominated by Dickinson’s towering presence. One of the most eloquent anti-war songs in metal history, “2 Minutes To Midnight” is driven by Smith’s phenomenal, uncharacteristically groovy riff and made even more memorable by Dickinson’s lyrics that reference the Doomsday Clock and drip with cynicism. The title track, meanwhile, is arguably Dickinson’s finest solo composition, a multifaceted excursion in Egyptology, rife with vivid imagery (“Green is the cat’s eye that glows in this Temple/ Enter the risen Osiris -- risen again”) and performed with theatrical flamboyance by him and the band. Harris’ nearly 14-minute suite “Rime Of The Ancient Mariner” remains a perfect encapsulation of Iron Maiden’s blend of power and storytelling, a prime embodiment of the genre’s escapist appeal. A summarized retelling of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s epic poem, “Rime” succeeds in every way that Piece Of Mind’s “To Tame A Land” misfired. Musically, and most importantly, lyrically restrained, Harris finds a balance between economy and bombast in a way he’d equal only sporadically for the rest of his career. His lyrics are simple, yet tell the story of the old seaman and that darn albatross vividly, giving Dickinson more than enough room to sell those lines with the flair of a stage actor. And when the opportunity arises to directly quote the poem (“Water, water everywhere and all the boards did shrink/ Water, water everywhere nor any drop to drink”), it’s a perfect fit. The dynamics of the track are masterful, shifting from the straightforward verses to an audacious extended middle section, which then segues into a chilling re-re-entry by Dickinson (“The curse it lives on in their eyes”) and a towering crescendo that explodes into an glorious dual solo break by Murray and Smith. 1994’s “Sign Of The Cross” would come close to matching that grandeur, but “Rime Of The Ancient Mariner” remains the band’s one great epic, the song that turned a generation of metalheads into unwitting humanities students. The band’s subsequent World Slavery Tour would soon become the stuff of legend: Eleven months and 187 concerts played, including triumphant performances in Eastern Bloc countries such as Poland and Yugoslavia in 1984, and in Rio de Janeiro in 1985, both of which would play a monumental role in broadening the global appeal of heavy metal (Brazilian metal innovators Sepultura were hugely influenced by the Rio performance). Maiden’s popularity skyrocketed, as they became one of the biggest moneymakers in the genre. However, now trapped in a perpetual write-record-tour cycle, the song “Powerslave” would take on a new meaning, the band finding themselves slaves to the power of commerce, art, media, and the expectations of their audience.

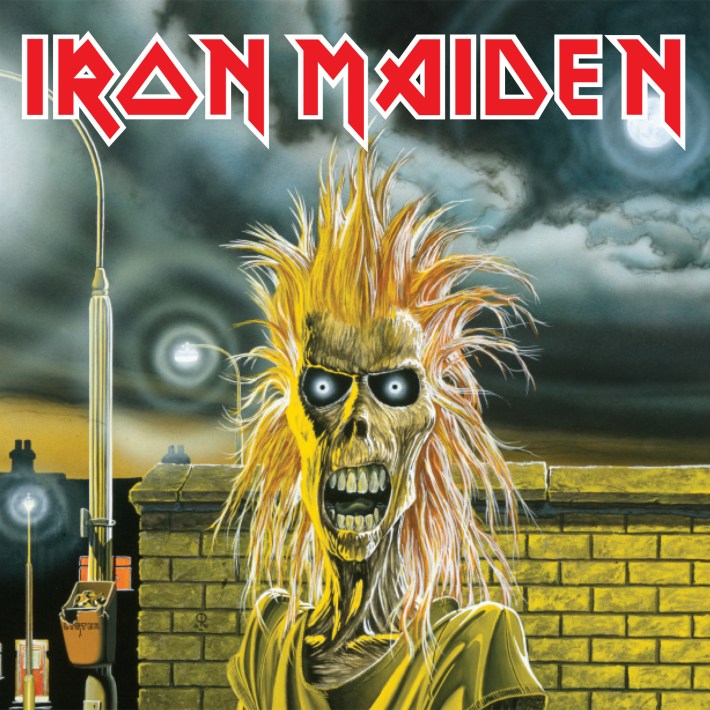

In a scene loaded with innovators but rife with amateurs that lacked marketing vision, Iron Maiden immediately distanced themselves from the rest of the New Wave Of British Heavy Metal on April 14, 1980 when they released their landmark debut album. While other emerging bands relied on a more DIY approach in regards to album packaging -- the specific reliance on distinct, creative, and brandable band logos set the standard for heavy metal for decades to come -- Iron Maiden delivered on all fronts. In addition to a striking logo that looked great on a T-shirt, the self-titled album boasted a stunning cover painting by Derek Riggs featuring a zombie in a T-shirt on a London street corner, staring daggers into the owner. That first appearance of the iconic Eddie is a classic lesson in Metal Marketing 101: Iron Maiden didn’t seem like a band, but more of a mysterious entity, and you just had to find out what this thing sounded like. Once you delve into the music inside that garishly designed package, what you hear is a young, fiery band hitting the ground running. Five years is a long, long time for a band to go from inception to first album, but that extended period in which to gestate, to hone that sound, to tighten it up by playing show after show, worked wonders for the East London crew. By the time the band was ready to record that first album, they were primed, completing it in 13 days. With the original UK pressing clocking in at 37 minutes, by far the shortest album in their discography, Iron Maiden is lean, ferocious, and despite the band’s dislike of the production -- Will Malone is credited as producer but the band says they were essentially left to do the bulk of the work themselves -- it sounds wonderfully gritty, straight out of the gutters of lager-soaked, blue-collar Leyton and East Ham. Just like 1979’s The Soundhouse Tapes demo EP, the album kicks off with “Prowler,” but this time around the tempo is picked up drastically, with more bite in the band’s performance, and more menace in Paul Di’Anno’s singing. Playful and cheeky, Dave Murray’s “Charlotte The Harlot,” the only solo composition the guitarist would contribute to the band, shows a seedier side of the band that they’d downplay in subsequent years. The single “Running Free,” meanwhile, is a Di’Anno tour de force, as the frontman is in full thug mode, exuding arrogance atop Clive Burr’s Gary Glitter-derived rhythm and Harris’ lively bassline. Di’Anno was always most at home when singing the band’s more abrasive material, and “Running Free” is his defining moment as a metal singer. Interestingly, the single “Sanctuary,” a brilliant, savage little tune originally written by former guitarist Rob Angelo that was released a month after the album came out, was left off the original UK pressing but included on the North American version that same year. And for good reason, too, as the song is an early Maiden classic, one that remained a live staple for a long time. For all that grit on the record, Iron Maiden most importantly lays the groundwork for the future sound of the band, the progressive side that Harris was always most keen on developing more. “Remember Tomorrow” is an extraordinary piece, an exercise in heavy metal dynamics that captures that ebb and flow of mellow and powerful perfectly. “Strange World,” by contrast, is strictly a mood piece, but sublimely executed. It’s the timeless “Phantom Of The Opera,” however, that sets the stage for a decades-long career. The best track on the album, Harris’ seven-minute piece is chilling and wrought with tension and menace, Di’Anno leering and looming, the guitars by Murray and Dennis Stratton intricate and searing. Stratton’s contributions cannot be underestimated, either, especially on these more prog-oriented tracks, as he came up with the bulk of the guitar harmonies and vocal harmonies, not to mention singing the backing vocals on “Phantom Of The Opera” himself. Unfortunately he was less enamored of their harder-edged material, and would leave the band in the fall of 1980. And what of “Iron Maiden,” that peculiar calling card that the band has never neglected to perform as the climactic conclusion to their concerts? It remains Harris’ strangest song, not making very much sense lyrically, built around a weird riff and even weirder syncopation. But that whole mess somehow works, damnit, and epitomizes a stupendous album that the most significant, game-changing debut since Black Sabbath 10 years earlier. These five young Cockney blokes cast their gaze beyond their dinky little island of a country and set their sights on the rest of the world. In just less than two years they’d be well on their way.

“If the band is doing really well with its first and second albums, and doesn’t do a great third album, there’s a kind of profound sense of disappointment that very often may mean the beginning of the end. But a really great third album can kick everything into gear, and in our case it was a great record. That really set the scene for the albums that followed… But of course, albums are not just about music, they’re also a product of their times. And Number Of The Beast, because it occupied a space and achieved such a legendary status by virtue of its position in the career of the band… it would be very hard to dislodge that.” (Bruce Dickinson to Martin Popoff, The Top 500 Heavy Metal Albums Of All Time, ECW Press, 1994) “I remember saying to them when it was finished, ‘You know, this is going to be a big, big album. This is going to transform your career.’” (Martin Birch to Mick Wall, Run To The Hills, MPG Books, 1998) “[During] the recording, I had a bizarre incident. I was driving up to London, and a car pulled out of a side turning and hit me. It turned out this bloke was a Black guy, he was going to a church to pick some nuns up. He started, there in the middle of the road, saying prayers. I was going, ‘Well, this is really odd.’ To cut a long story short, the bill that I got for the damage of my car was £666 exactly. When I picked the car up, I refused to pay the bill, I said, ‘You either make it 668 or 670, I’m not paying that figure.’” (Martin Birch, 12 Wasted Years, 1987) By the end of 1981 it was clear to Iron Maiden and its management that if they wanted to take the next big step in their career, a serious change would have to be made. Not only was the offstage behavior of Paul Di’Anno becoming an increasing distraction, but his gritty singing style, while terrific on the 1980 debut, lacked the potency and range that suited where Steve Harris wanted to take the music next. Immediately after the band’s performance at the 1981 Reading Festival, their last show in support of the Killers album, manager Rod Smallwood approached Samson singer Bruce Dickinson about possibly joining the biggest band in the NWOBHM scene. After auditioning that September, Dickinson was hired, and the rest, as they say, is history. Iron Maiden was on the cusp of a major commercial breakthrough, but they had plenty of work to do. For the first time the band had to come up with new songs from scratch, and were given three months in which to come up with the most important album of their lives. And all the band did was knock it clear out of the park on The Number Of The Beast. Looking back at The Number Of The Beast, what’s most extraordinary about it is not only the anthemic quality of so many tracks, but the sheer stylistic variety of them all. Each track stands vividly alone, distinct and instantly memorable. Harris comes into his prime as a songwriter on this record, contributing five classic songs specifically created to flaunt Dickinson’s staggering voice. Always an unforgiving songwriter, Harris’ material constantly demanded seemingly inhuman vocal range and an ability to clearly enunciate verses with twice as many words as they needed, but in Dickinson he had the perfect frontman, one who could sing the hell out anything he was handed, no matter how difficult, no matter how breathless the verses. Just look at some of the lines on this album: Call to arms defend yourselves get ready to stand and fight for your lives Judgment day has come around so be prepared don't run stand your ground As the guards march me out to the courtyard Somebody calls from a cell "God be with you" If there's a God then why has he let me go? Dickinson’s status as a heavy metal singing legend is undeniable, but it was his incomparable performance on The Number Of The Beast that cemented it. He might not have been able to make concrete contributions to the songwriting -- ongoing legal hassles with Samson prevented him from earning songwriting credit -- but he carries the entire album on his back. Dickinson bursts onto the scene on the rampaging Viking tale “Invaders,” displays operatic flamboyance on “Children Of The Damned” -- a cousin of Iron Maiden’s “Remember Tomorrow” but leagues better -- and brings audiences into the cold cell of a condemned man on the stirring epic “Hallowed Be Thy Name.” The power and command with which he delivers the line “The sands of time for me are running low” is awe-inspiring, a reflection of how Iron Maiden’s scope finally got out of the clubs and into the stadiums. As great as Iron Maiden and Killers were, and still are, The Number Of The Beast is next-level. The album also marked the first time Adrian Smith contributed to the songwriting, and he makes an immediate impact. An homage to the classic cult TV series of the same name, “The Prisoner” displays a remarkable knack for melody, groove, and simplicity, which would become a Smith hallmark. “22 Acacia Avenue,” meanwhile, was a holdover from his days in Urchin and Evil Ways and is fleshed out with the help of Harris, transformed into a multihued and surprisingly compassionate sequel to the leering “Charlotte The Harlot.” And of course, there are the two most ubiquitous, notorious -- and popular -- songs on the album. Featuring one of the most distinct intros in heavy metal history and propelled by a brilliant drumming performance by Clive Burr -- who shines on the entire album for that matter -- “Run To The Hills” is Maiden at its most bracing, its brisk tempo echoing the gallops depicted in Harris’ portrait of First Nations oppression, perfectly suited for the live setting, something that immediately engages audiences. The title track, though, is a masterstroke. A perfect embodiment of heavy metal’s most crucial tenets -- flamboyance, melody, theater, escapism, menace, provocation, power -- Harris’ surreal fever dream is fiery and uncharacteristically grim, highlighted by a sensational solo duel between Murray and Smith and again delivered with theatrical flair by the indomitable Dickinson. Watch an audience erupt in reaction to this song in an arena, and you’ll understand the unique, deceptively simple power of this song. It is heavy metal incarnate. The Number Of The Beast might be Iron Maiden’s best album, but it’s not a perfect album. Featuring Burr’s only songwriting contribution to the band’s discography, “Gangland” is an unfortunate misstep. While it’s memorable enough, it fails to measure up to the very high quality of the other seven songs. During the rush to complete the album, the band had to choose between the speedy “Gangland” and the darker, mid-paced “Total Eclipse” for inclusion on the album, with the other serving as the B-side on the “Run To The Hills” single, and Harris readily admits he wishes he’d chosen the far superior “Total Eclipse.” The song was subsequently included on the 1998 reissue of the album, and while “Gangland” still sticks out, “Total Eclipse” significantly strengthens the latter half. Upon its release, adorned with Derek Riggs’ imposing yet witty artwork -- the Devil manipulating Eddie with puppet strings, but with Eddie above the Devil doing the exact same thing -- reaction to the album was immediate, from both ends of the spectrum. “Run To The Hills” became the band’s first UK top ten single, the reception in the metal press was overwhelmingly positive, and most hilariously, it was singled out by the American Religious Right as being Satanic. In the early ‘80s, there was no better publicity for a heavy metal band than some good old Satanic panic, and while trying to fend off the patently false accusations was an enormous hassle, the notoriety played a large role in breaking Iron Maiden into the difficult American market. With The Number Of The Beast, the band was set. As Dickinson has often stated, it marked the rollercoaster car reaching the top of that crucial first climb. The pace of the subsequent 10 years would be insane, bringing the band unprecedented success and eventually taking a serious toll on everyone involved. This album was the catalyst, and in retrospect, the artistic pinnacle of a legendary and multifaceted career that shows no signs of stopping after over 40 years.