Anyone who has heard the music of Silk Sonic, the R&B superduo comprising Anderson .Paak and Bruno Mars, will immediately recognize that it’s heavily steeped in early-'70s soul aesthetics. From just the first two singles, “Leave The Door Open” and “Skate,” there’s no doubt that the Silk Sonic project is part homage, part parody -- and clearly self-aware. But if you can get beyond the devilishly smooth retro façade and tongue-in-cheek lyrics, you’ll find that the tunes contain truly challenging and inventive musical constructs. While Mars and .Paak are plainly channeling the refined harmonic language of Stevie Wonder and Holland-Dozier-Holland, it would be foolish to dismiss this effort as a mere nostalgic indulgence. Silk Sonic may be superficially steeped in the 70s, but they’re also forging new paths compositionally.

“Blast Off” is the last song on the LP, An Evening With Silk Sonic, and it beautifully encapsulates this adventurous spirit. Its underlying musical architecture contains many surprises, and even some harmonic innovations—things I’m not sure I’ve ever heard before.Check it out.

The Suspense Is Killing Me

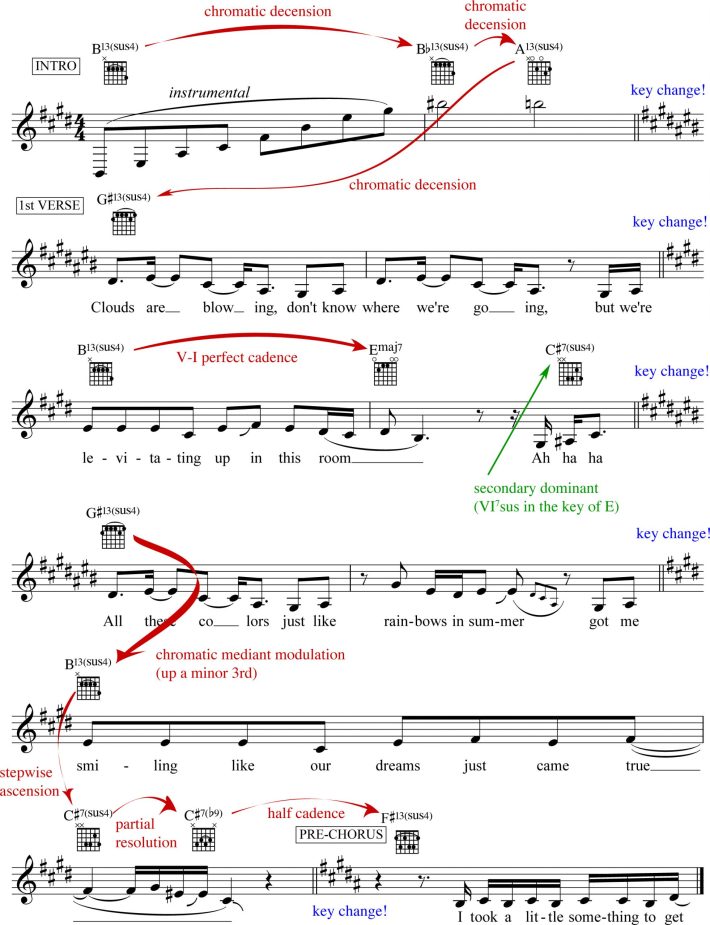

“Blast Off” opens with a suspended chord, a B13sus, played with strings and vibraphone, using an arpeggiated spread voicing over three octaves. It’s a kind of harmonic announcement that builds anticipation for what’s to come. Indeed, this opening passage soon reveals itself to be highly predictive:we discover that the central characteristic of the song, the thing that makes it so alluring, is its prodigious use of suspended chords.“Blast Off” uses suspended chords everywhere, even in places you would least expect to hear them.

What are suspended chords? Previous In Theory columns discussed how different kinds of chords using various scale degrees can invoke a feeling of tension and release, a sense of moving away from, and back towards home. The classic example is the “V7-to-I” perfect cadence, where the dominant (V7) chord is highly “unstable” and yearns to resolve to the unflinching tonic (I) chord. Suspended (or “sus”) chords are also unstable, but they don’t possess much tension on their own. They can sound rather consonant while still feeling unresolved.They sort of “float” -- as though needing to be grounded. See Figure 1 below.

In European classical music, sus chords served a predefined role: to set up an inevitable musical resolution.This tradition is based on what we call “tertian harmony,” where the fundamental building blocks comprise stacked 3rd intervals (Major and minor), as shown in the first measure of Figure 1 above. When a 4th scale degree displaces the 3rd, as in the second measure of Figure 1 above (with the note C displacing the note B), what usually follows is that the 4th resolves back down to the 3rd, as though it’s being pulled by a magnetic field to a more stable position.

But in 20th-century Western music (whether we’re talking about pop, rock, and jazz -- or even Stravinsky, Debussy, and Bartók), sus chords often don’t function in this traditional manner. Indeed, sus chords don’t need to carry out any particular function. This is where “quartal harmony” comes into play, in contrast to tertian harmony. Suspended chords -- whether the sus4 variety we’re discussing here, or the alternate sus2 type -- are essentially built from stacked 4th intervals, and they don’t possess the same air of predictability as chords based on stacking 3rd intervals. Employing sus chords in a quartal harmonic structure can lend itself to a less controlled sound, one with greater emotional ambiguity and more room to explore complex themes.

Joni Mitchell frequently uses sus chords in precisely this way, and specifically for their unresolved character. Great examples include her songs “Sistowbell Lane,” “The Dawntreader,” and “Marcie.” In Herbie Hancock’s iconic 1965 modal jazz tune “Maiden Voyage,” he deploys dominant sus chords (i.e., sus chords with a flat 7th degree) almost exclusively -- and in a manner that doesn’t comport with traditional demands of tertian harmony. These chords neither suggest where the harmony is coming from nor in which direction it’s headed. In essence, like with a lot of Joni Mitchell’s music, the sus chords in “Maiden Voyage” operate not as musical plot points in the story, but more as splashes of color on the canvas.

A few years ago, Robert Glasper explored this concept using quartal harmony in his exquisite version of “Maiden Voyage,” which he beautifully blended with Radiohead’s “Everything In Its Right Place.” It’s worth checking out. And Silk Sonic? “Blast Off” songwriters Bruno Mars, Anderson .Paak, and D’Mile are using sus chords in a similar manner: combining mostly quartal harmony with a little bit of traditional tertian harmony. See Figure 2 below.

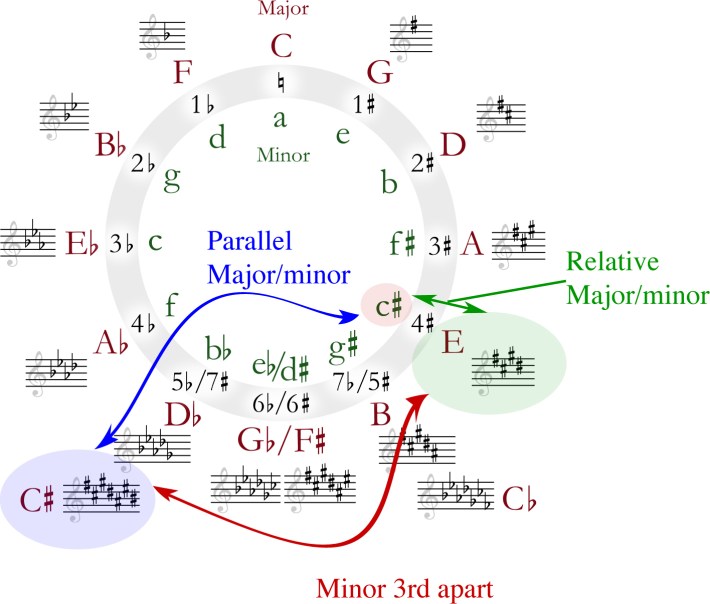

The G#13sus to B13sus motif creates a huge lift, and even though it’s a recurring theme, it feels unexpected every time it happens. This is because the modulation has the effect of a minor 3rd key transposition, which is one type of “chromatic mediant” modulation.(For more on this, see the In Theory article on Nirvana’s “In Bloom.”) Changing key centers upwards by the distance of a minor 3rd sounds so dramatic because it’s akin to shifting the axis of the song from a Major key to its parallel minor key.For example, going from C# Major to E Major feels like going from C# Major to C# minor (because E Major and C# minor share the same key signature, as the latter is the “relative minor” of the former). See Figure 3, below. While the key centers of C# Major and E Major share some common tones, the really crucial ones (the 1st, 4th, and 5th scale degrees) are different -- and this is what makes the shift so effective.(For more detailed background on this, see the In Theory article on Lorde’s “Solar Power.”)

What follows next is the B13sus to EMaj7 cadence, which is the song’s only recurring instance of a traditional V-I resolution. It’s when Anderson .Paak finishes the line, “levitating up in this room,” and the release of tension feels both relieving and nourishing. But the respite is fleeting, as we’re quickly lifted back into suspension with the C#7sus pivot, returning us to G#13sus. In the transition from verse to pre-chorus, Mars and .Paak deploy a kind of “half cadence.” We hear the C#7sus resolve to the C#7, which craves resolution to F#Maj in a Bach-approved V7-I perfect cadence. But when the F# chord arrives, it comes in the form of ... you guessed it, an F#13sus, resulting once again in meandering, unresolved harmonic tension. This sus chord undergirds Bruno Mars’ line, “I took a little something to get here, yeah, yeah,” and I can imagine him singing that melody with a sly wink and nod, knowing he’s subverted expectations by sneaking in that deceptive cadence. Seriously, these guys know what they’re doing.

As with “Maiden Voyage,” the sus chords in “Blast Off” feature upper extensions — 9ths and 13ths — which add further color to the harmony, imparting a misty complexity to the sound. In the 1940s, Charlie Parker popularized the use of altered chord extensions against V7 chords by playing virtuosic solos using the #9, #11, ♭13, as well as the ♭9 against V7sus chords. When using upper extensions, “Blast Off” mostly avoids the altered variety, but the song does slip in the ♭9 to great effect on the C#7sus at the end of the second verse. It’s a tasty surprise, a kind of amuse bouche to whet the palate and stimulate our musical appetite for the pre-chorus that’s about to come.

Your Chord Doubles As A Floatation Device

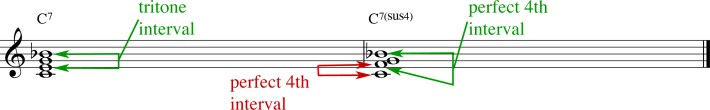

Why do dominant sus chords feel so soothing and “floaty”?Consider that standard dominant 7th chords contain the root, Major 3rd, perfect 5th, and flat 7th. It’s the 3rd that makes the chord feel grounded, because it communicates the chord’s essential quality, or brightness. The flat 7th forms a “tritone” interval with the Major 3rd, which is quite dissonant -- in fact, it’s the most dissonant interval that exists in the Western harmonic system. So the standard dominant 7th chord possess a volatility that craves resolution to a more stable and consonant chord. In contrast, dominant sus chords replace the 3rd with the 4th, so the tritone interval transforms into a “perfect 4th" -- a relatively consonant interval.See Figure 4 below. The resulting sound feels ambiguous, and that’s the salient characteristic that distinguishes quartal harmony from tertian harmony.It possesses a kind of gentle instability, where the chords hover and glide, as though gravity itself has been suspended.

I suspect Mars’ and .Paak’s use of so many dominant sus chords was not a haphazard choice. If your goal, as the lyrics metaphorically state, is to “blast off into the sky,” then suspending gravity can work in your favor. Clearly, everything in this song was deliberate, and not a thing miscalculated.

A Source Of Inspiration?

The chorus of “Blast Off” follows the same harmonic structure as the verses. The chord changes are so savory, I totally get why the Silk Sonic would want to continue marinating in them.Indeed, the progression is unusual and truly evocative ... but is it unique?See Figure 5, below.

When I first listened to “Blast Off,” I assumed I hadn’t heard that progression before ... until I realized it shares the same harmonic structure as the “A” section of Stevie’s Wonder’s “My Cherie Amour.” I’ve always been awestruck by Stevie’s deft harmonic pivots, his ingenious musical phrasing, and the richness of his harmonic vocabulary — and I imagine Mars and .Paak feel the same. So it makes sense that Silk Sonic would want to build on Stevie’s work, which they do cleverly, using the subtle chord substitution shown in Figure 5.

Blast Off To The 7th Degree

The song’s coda is worth examining because it’s here that we find one, and possibly two, stirring musical innovations. Mars and .Paak use this closing passage not to “blast off,” per se, but to glide up gently toward the sky. Each repeating passage cycles up chromatically, by a half step.However, it’s not a perfunctory or gimmicky maneuver, which is how these things are typically executed. (Beyoncé’s “Love On Top” comes to mind immediately.) The way Silk Sonic accomplishes this chromatic ascension is pretty inspired.

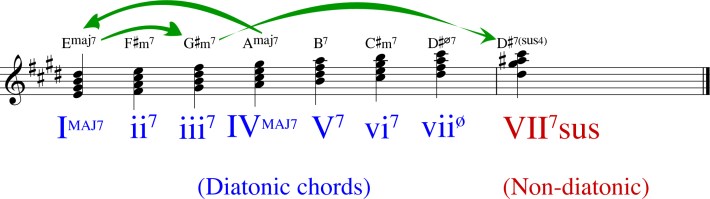

They begin with a repeating progression comprising the following changes: IVMAJ7 - IMAJ7 - iii7 - VII7sus. This passage is in the key of E, so we have:AMaj7 - EMaj7 - G#min7 - D#7sus. The D#7sus chord is the curious one.See Figure 6 below.

As we’ve explored in previous In Theory articles, “diatonic” chords are those that live in the song’s key center. Figure 6, above, shows how we can derive them by stacking 3rds on each degree of the Major scale in order to generate 4-note chords.

In the coda of “Blast Off,” instead of using the diatonic 7th degree of the E-Major scale, which is the D#ø7 (or D#min7♭5), they substitute a D#7sus -- thus, staying consistent with the suspended-chord theme. The musical effect of this chord substitution is quite lovely, and I can’t think of any other pop song in which I’ve heard this before. The Hoagy Carmichael standard, “Georgia On My Mind,” popularized by Ray Charles, comes close: it uses the diatonic chord of the 7th scale degree (the half-diminished, or min7♭5) as a kind pivot chord in a proxy ii-V-type turnaround. So it’s not the same thing as what we hear in “Blast Off.” Another song that comes close is the Beatles’ “Yesterday,” in which Paul McCartney substitutes a non-diatonic minor-7 version for the 7th scale degree chord (an Emin7, in the key of F).Again, it’s similar to what Mars and .Paak are doing, but it’s not nearly as cool. If Silk Sonic’s use of the VII7sus chord is in fact a one-off in pop music, I hope it doesn’t stay that way.It’s such a great sound, and something I plan to integrate into my own compositional vocabulary.

But wait, there’s more ... How does Silk Sonic manage to spiral the progression upward, chromatically, while avoiding the jarring sound of half-step key changes? They further exploit their suspended version of the 7th scale degree by following it with the same chord repeated a whole-step up.In the first iteration, it goes from a D#7sus to an F7sus, with the latter serving as a dominant V pivot chord to lead us to the IVMAJ7 chord in in the new key — a new key that happens to be a half-step up. One reason this is so clever is that we’ve already heard this “sus-chord-whole-step-up” maneuver several times in the song, in a different context (see Figure 2, where the arrow indicates “stepwise ascension”). So when they deploy it here, it feels familiar, not like some ad hoc device they’ve shoehorned in. They repeat this sequence several times, with each iteration resulting in a half-step rise — and it feels totally natural, even inevitable. This is master-level songcraft.

What If?

It’s too bad so much attention is getting siphoned into the superficial trappings of Silk Sonic’s ‘70s soul gambit, while the brilliance of the underlying musical architecture goes mostly unnoticed. Maybe it’s Silk Sonic’s own fault for inviting that kind of focus — what, with the costumes, the lyrics, and the period-accurate production techniques. I do wonder if Mars and .Paak chose the ‘70s soul idiom not just for the fun and nostalgia factor, but also because they understood it’s the kind of musical vessel that can reliably contain inventive and complex harmonic writing. Imagine if they’d composed the same music but without the Motown/Philly Soul veneer, without the vintage instruments and retro orchestration/production style. Would mainstream audiences accept that kind of sophisticated harmonic language minus the old-school disguise? Will any modern pop music that uses rich chromaticism, adverturous counterpoint, chords with upper extensions, and shifting key centers inevitably come across as old-fashioned, even if it arrives dressed in 21st-century clothing? We can ponder these questions, but for now I’m going to take An Evening With Silk Sonic for another spin.Blast off!