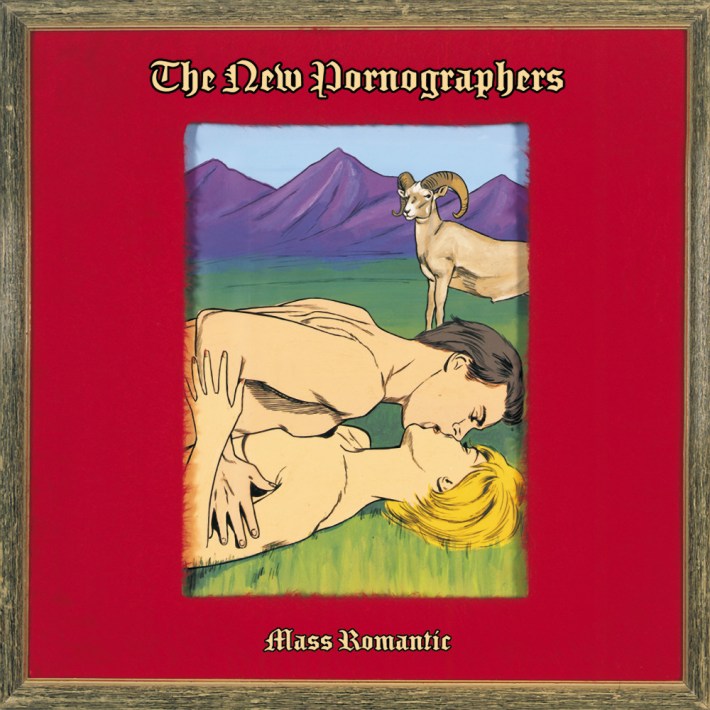

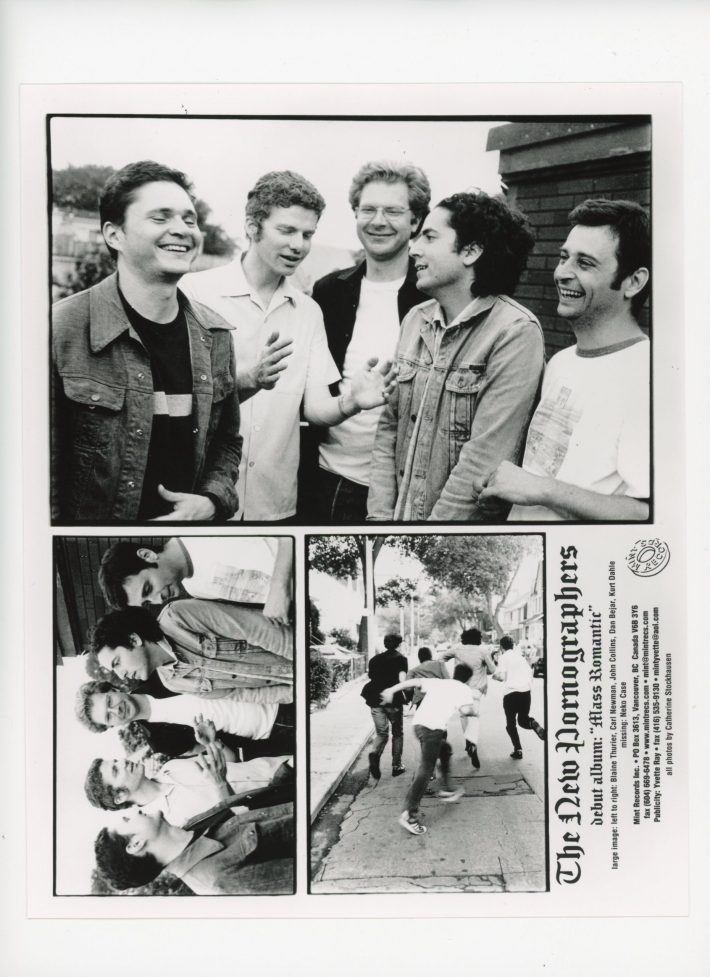

Mass Romantic, the incredible first album from the New Pornographers, turned 20 years old last year. For pandemic reasons, the Vancouver-founded power-pop supergroup was not able to properly celebrate that anniversary. This month they're making up for lost time: A deluxe reissue of Mass Romantic is out this Friday on Matador, and the New Pornos have been playing the album in full at a series of 21st anniversary shows with both Neko Case and Destroyer's Dan Bejar in tow.

With Mass Romantic season upon us, I got in the spirit a few weeks ago by connecting with New Pornos leader Carl Newman over Zoom to go track by track through his band's classic debut. He was happy to oblige: "For whatever reason I think I probably remember more about this album than any other album," Newman told me. "It just felt like a special time in my life. I guess it was, in retrospect. It changed everything for me. I was just an unemployable musician, and then I became cool. It was nice."

1. "Mass Romantic"

How did this become the opening blast?

CARL NEWMAN: It just had that obvious gallop and vibe that just seemed to work well. That was one of the middle songs. When I'm writing a song it's always a long process. I couldn't tell you how I wrote that song; it kind of came together slowly. But the initial idea, I'm pretty sure it was just a burst of being super high. You know when you smoke pot, you have about a 20-minute window where you're of any use? I think I was really high and I had this idea. I think it was that initial kind of [sings verse melody] and I somehow got it down before I fell asleep or started watching TV.

The main thing I remember about that song is -- that song has a big ending that's always very effective live. It breaks down, and people go, like, "Yeah! Cool!" But when we did it live in the studio, it just went straight from that Beach Boys-y section into that sort of [sings "This boy's life..."], that rock section. And when we were mixing it, John and I just thought, "It sounds clumsy. It just sounds like we tacked another part onto the end of the song." So we thought, how can we make it work? So we inserted I think about eight bars, and I just played an unplugged electric, and I sang into the talkback mic. It was almost as if I had recorded it on a Zoom call.

So if you listen to it, it has that kind of lo-fi feel. It has that unplugged electric and me going, "This boy's life among the electrical light!" And then, that worked. When you broke it down into that weird lo-fi section and then had it build up into this big outro, it was very effective. But that was an example of arranging after the fact. I felt like we really saved that one. And when we play that part, I always remember it. It's like, "Wow. This song is so much better because we inserted this little breakdown." That was so effective, we realized, people love that shit. People love it when you break down, and get quiet, and then get loud again. So I think we probably used that trick a bunch of times.

Let's back up for a second. Where did you make the album? Who all was there?

NEWMAN: There were many separate sessions. It was not always the same people. It was always John and I. There was a huge amount of me and John Collins. Everybody came in and out. Neko was the one who was never there. She was the one where we had to just somehow get her for a day or two. But the rest of us lived in town.

Dave Carswell who's part of JCDC [Studios] with John Collins, he used to have a studio set up in the basement of his parents' house. So we did a lot of the earlier work on the record there. That was very much just a basement hangout. We would drink a lot of gin and tonics and record. Later we moved into our friend Rodney Graham's art studio. He's actually a pretty famous conceptual artist, and he had a great art space right in the middle of town. It was right at Granville and Robson Street, which is as central in Vancouver as you can possibly get. We spent a lot of time in there, John and I.

It's funny, I have this weird memory. The first X-Men movie came out when we were making Mass Romantic. My life was nothing but going to my job and leaving my job and going to the studio and working on this record. And that was literally all I did. And after about four or five days of burning the candle at both ends, I would just call off work. I just couldn't do it anymore. I just couldn't exist on no sleep anymore. But I remember going to see X-Men and feeling like, "I'm being lazy." Like, "This is three hours that I should be using to make this record. I shouldn't be watching this X-Men movie." I remember feeling guilt as I watched it. And it seems funny looking back because we didn't have a deadline. It was just I wanted to get it done, and I felt like, "I've got to devote all my time to making this record." It wasn't like when it was done I was going to quit my job and everything was going to be great. But I remember feeling like, "This is important." And looking back, I can't remember why.

Well, I guess it was.

NEWMAN: Yeah, it was.

What was your job at the time?

NEWMAN: I worked at a place called Larrivée Guitars. They make acoustic guitars. It was a decent job for a musician to have. My job was basically to set up guitars. So I probably wrote a few things while I was just sitting around at work slacking. It was a funny job because if you were slacking and you wanted to pretend that you weren't slacking, you'd just start playing guitar. It was very much a win-win.

Before we move on: Why is this the title track?

NEWMAN: Somebody in the band just said, "Why don't we call it Mass Romantic?" 'Cause we knew "Mass Romantic" was the first song. And somebody just said, "Mass Romantic's a good title." And I thought, "Yeah. It is!" So it was Mass Romantic. And then it became a pattern, a kind of unintentional pattern. Mass Romantic started with "Mass Romantic." Electric Version started with "Electric Version." Twin Cinema opened with "Twin Cinema." And then we didn't do it again till Brill Bruisers. It felt like returning to the tried-and-true formula: We're gonna open with the title track.

2. "The Fake Headlines"

Was this inspired by any particular media experience or something that you had read?

NEWMAN: I think I just had a random idea. The idea was it was just a pathetic love song where a guy goes to a carnival and gets one of those fake newspapers made. I'm not sure what it says in the fake newspaper. I guess it must say "COME BACK" or something like that. I still like the idea of the carnival, you know? There's something about trashy low-rent carnivals. When you're a kid they seem sort of mythic and magic, and then later you realize, "Oh. It's just kind of trashy and scuzzy." Maybe that's applicable to a lot of other things in life.

A lot of these songs, I was never concerned at all about any kind of narrative, really. I mean, "Fake Headlines" had sort of a narrative, but I was just trying to make music that sounded cool. Like I'd listen to old Eno records and think, "Eno's just mumbling some cool word salad. This fucking rules!" So I think I thought to myself, I wasn't going to be overly concerned with trying to be Springsteen or some sort of narrative storyteller. I just wanted to make cool rock music. And I think I was taking some notes from Bejar. I'd listen to the lyrics in his songs and I thought, "Maybe I should do stuff like that. Maybe I should write more about revolution in the streets." Because it will tie the record together a little bit more.

There was a certain freedom there, when it doesn't feel like anybody's listening. You feel like, "Well, who cares?" You're not wondering what people are going to think because those people don't exist. You're not second-guessing. Now I do that. Now I know there's this phantom audience, and I don't know anything about them. And I can give them a personality. I can think they love me or hate me or are out to get me. But there was no audience back then. It was a self-contained record. So I thought, "Whatever!"

This was another one where I played an unplugged electric through the talkback mic. That was the intro to "Fake Headlines" as well. That was the intro into the medium-fi band kicking in. So it was definitely a pattern. Now it seems absurd. Now it's the kind of thing I wouldn't do because I would think, "That's wrong." If I played a part into a talkback mic or did something in a really lo-fi way, I'd think, "I can't do that. We're supposed to be a pro band. I can't be working in this lo-fi way." But yet, working in that lo-fi way was what got us our foot in the door. It's what gave us our little career. So I try to remind myself things like that. We were purposely lo-fi in the beginning, and it worked. Maybe not purposefully -- maybe it was just laziness. Like we didn't feel like walking into the next room and setting up an electric and getting a good guitar sound. So it was like, "Why don't I just sing it into this mic here and we're done?"

3. "The Slow Descent Into Alcoholism"

Autobiographical or nah?

NEWMAN: Yeah, very much! Again, I wasn't overly concerned with the narrative. Although the song title tells you about 75% of what you need to know. I was thinking about the fact that there are so many sad songs about alcoholism. Obviously it destroys people's lives and it causes anxiety, despair, depression, so much sorrow. But I also thought, so many good things in my life came from me being drunk! Because it just kind of loosened me up. I think that's why people drink. When you're a shy person, you have a few drinks and all of the sudden it's like, "Wow, I'm funnier! I'm more charming! I met a girl last night that I probably wouldn't have said hello to if I hadn't had a few drinks." It was basically a song about that dichotomy, that it can be such a horrible thing, but hey, there's no denying that there's fun to be had there. So I thought I would write this kind of fun sad song about, "Yeah, I'm doomed. I'm doomed but I'm having fun." Which was like "Salvation holdout central" -- it was like, when am I going to save myself? Well, not today. Now I feel a little guilty about it 'cause I wasn't trying to glamorize it. But again, I didn't know anybody was listening. It just was what it was.

But now I kind of regret that song because people always liked it, and I think people always wanted us to write more songs like that. It didn't take me long to get sick of writing songs that went [mouths jaunty 4/4 rhythm]. Yeah, it's cool. I can see why people like them. But I don't want to do that all the time. But it worked! That Sesame Street feel, it's very effective.

It's funny that you compare it to Sesame Street because the song has kind of a drunken swagger to it. Like you're just kind of pounding along and could topple over at any moment.

NEWMAN: Yeah, I think we always had that, which I like. I always call it the train always coming off the tracks. Like one wheel coming off the tracks. Is it going to go? Nope, the wheel goes back on the tracks again.

There was one thing in "Slow Descent" which was very much an accident. I like to claim it's intentional now, but it was very much an accident. And it was that "My slow descent went something like this" and then the pick slide goes [makes descending pick slide sound]. I did this descent down the neck of the guitar, and only later did I go, Oh, what an amazing happy accident!" It makes us appear smarter than we actually were. But maybe on some unconscious level I knew that would be a cool thing to do.

4. "Mystery Hours"

NEWMAN: That was one of the first four songs we recorded. Around '99 we had a four-song demo, and it was the four songs exactly like they appeared on the record. It was "Mystery Hours," "Letter From An Occupant," "Execution Day," and "Breakin' The Law." And so that one was very much an early song. Remember when I was talking earlier about how I should try to write something like Dan would write? I think "Mystery Hours" was something like that. I was thinking, if we want this record to have any kind of focus, it felt like Dan's songs had this kind of vibe already. And I thought, "OK, let's keep going down that vibe." And I think "Mystery Hours" was one of those.

Also kind of a cousin of "Slow Descent" thematically in that for me the mystery hours were -- it's kind of another way of talking about something like a blackout. Sometimes something good happens in there, but sometimes something really awful happens in there. That was what they were. Looking back, a lot of it is just being a sort of uneasy person with a lot of anxiety, and I think you're trying to get out of that headspace. So some people use alcohol, some people use drugs. And I think music was also like that for me -- a means of escape. And sometimes they would all combine together. Sometimes music and alcohol and drugs would just mix together. And I guess that's what I thought of as the mystery hours.

I'm making it sound like I was a terrible alcoholic drug addict. But I wasn't. I think I liked to dabble in the iconography. It was rock 'n' roll after all. We wanted to make something that was rock 'n' roll. Like, it was not a joke, but we also wanted to play around with rock 'n' roll cliches. That's why there's a lot of things on the record like "Oh yeah!" and "Come on!" and "Uh huh!" That was a very conscious, "We're making rock music." I think I had given up on trying to be relevant. I thought, "Let's just make our warped take on what we think a rock 'n' roll record sounds like."

All of the songs are very blown-out and maximal, lots of stuff happening, very in-your-face. But I feel like this is one of the most. It just keeps getting bigger, and the chorus is just like rockets going off or something. Was that a goal to make it sound as maximal as possible?

NEWMAN: I think we definitely were. And I think we were learning a lesson as we go, that when you're trying to do that kind of maximalism, you lose some things. Like, there's not a huge amount of bass and drums on that song 'cause there's so much stuff happening.

Another thing I forgot to mention but was very important is that Fisher Rose was the drummer on this. Because Kurt [Dahle] didn't join until later. So those four songs I mentioned [from the demo], our friend Fisher was the drummer. I remember that beat on "Mystery Hours" is such a Fisher beat. In my mind he invented that beat. I'm not sure if I'd ever heard it before him. And I thought that really made the song. I thought that hard-driving angular beat -- which I'm pretty sure Spoon took. I swear a few years later Spoon used that beat on a song called, like, "My Mathematical Mind" or something like that. Not that Fisher invented that beat, but I'd like to think Spoon was using the "Mystery Hours" beat, but they probably weren't. They probably just were being Spoon.

But you gotta bring up Fisher because he was very key at the beginning. That kind of hard-driving angular pop music, I think he added a main ingredient that we kept even when he left. I think we had the program in place. When we started we were trying to write this simple computer program that was New Pornographers, and he added that element, and we said, "OK, let's keep doing that." For years afterward I would still hear beats like that and I would think, let's have what I call the hard, angular beat. There's probably a better word for it.

5. "Jackie"

The New Pornographers is obviously such a different band from Destroyer in terms of aesthetics. When he brings you one of his songs, what has that process always been like? Does he write it as a New Pornographers song or does he turn it into a New Pornographers song?

NEWMAN: This one was very much turned into a New Pornographers song. I saw him play an acoustic Destroyer show. It was probably around 1999 I guess. Maybe early 2000. You gotta remember we live in Vancouver where there's a lot of pot. Anyways, I was really stoned when I was watching this solo Destroyer show. And he played "Jackie" and "Testament To Youth In Verse." And I was there in the audience, and it suddenly occurred to me, "These songs could be in my band. These amazing songs could be in my band!" So I went to him and afterwards and said, "Those songs! 'The bells ring no' and 'visualize success,' those two, we gotta use them in the New Pornographers." And he said, "Cool."

For whatever reason, "Testament," we sat on that until the next record. But we went to the studio to do "Jackie" and I remember there were things that I added. It was just arrangement. I just love the line "Visualize success but don't believe your eyes." In the original version, he just said that once. It was just kind of a passing line. And I thought, "That's good. Why don't we just hit that really hard?" Like, why don't we have a part where we're just yelling that a few times? That might have been the only thing I contributed.

But it was like that in the earlier days. Starting on Electric Version or Twin Cinema, a lot of his songs were a lot more fully complete and we just played them. But "Jackie" I remember we had to turn it into a New Pornographers song. And it's still one of my favorite Pornographers songs. I remember we had a Wurlitzer around. So much of the Pornographers has been based around what's in the room. When we were recording that, there was a Wurlitzer there, so we thought, "Let's put Wurlitzer on it!" So it became this kind of groovy, Wurlitzer-driven song just because there was a Wurlitzer there. Just like on the next record there was a pump organ there, so there's a lot of songs with a pump organ.

It was great working on the Dan songs because that's when I began to have a sense that "this is good." Like when I'm listening to my own songs I can't see the forest for the trees, but when we're playing songs like "Jackie," I thought, "This is great!" But lots of bands were great that nobody knew about, that lived and died in obscurity. So I thought, it's great, but what's that worth? It wasn't even worth thinking about.

6. "Letter From An Occupant"

When first hearing about the New Pornographers, I remember this being the single, the song you've gotta hear. Did you identify this one early on as a single or a standout track?

NEWMAN: No, not at all! We had that four-song demo. and I gave it to people. I sent it to Sub Pop because [Newman's previous band] Zumpano was on Sub Pop, and I never heard back from them. And I sent it to my friend Nils -- he was at Matador, but I met him when he was at Sub Pop. So I sent it to them and never really heard back. Although years later Nils would tell me that they listened to it. But it was a cassette, and they didn't have a cassette setup in the office, so it was always a big hassle to put on the New Pornographers demo. Nothing came of it. I sent it to the head of Sub Pop and I sent it to my friend at Matador and I sent it to some really tiny labels, and nobody bit. I remember just being shocked, like, "Is it just me?" A couple years later everybody would be telling me what an amazing song "Letter From An Occupant" was, but yet, it was there in the world, and I was sending it to people, and the response wasn't like, "Oh, we gotta sign these guys."

But then, in early 2000, this clothing store in Vancouver called the Good Jacket decided they were going to put out a benefit CD for, I think, the Vancouver Food Bank. And so they asked us to put a song on it. I thought, OK, how about this song "Letter From An Occupant." Nobody else wants it! So we gave it to them, and that was the first song. And it got quite a lot of attention! People went, "Who's this new band?" And we called ourselves "The New Pornographers & Neko," which was a cute way of referencing that classic band and also referencing the fact that Neko was singing it.

Mint Records, when then they saw the reaction to the song, that was when they wanted to sign us. They had also heard our demo. They'd heard our four songs. Their response was also kind of a shrug. But that was when I think people started to realize, "This song has been put out in the world and we're getting a lot of positive feedback." And so because of "Letter From An Occupant" on that compilation, Mint said, "We want to put out your record now." And then we put out the record. So yeah, "Letter From An Occupant" was definitely -- it was our foot in the door, but it was waiting at the door for a couple years before anybody answered.

Did you write that one with Neko in mind? Do you know ahead of time which songs you're going to hand off?

NEWMAN: I know I must have. And I remember very well playing it for Neko and feeling very embarrassed, whenever that was -- 1998? Just feeling like, "OK, here's my shitty song, Neko. Will you sing it?" It's hard to remember what I was even thinking. But the idea that Neko would sing a couple songs, maybe because there was Dan in the band and I was in the band and Neko was in the band and it was hard to pin down Neko for anything, maybe we could only get her to sing lead on two songs and that was it. And that became kind of a model. That continued. Like, "Oh, we can never get her to sing." So we would get her to sing two lead and a bunch of backups because backups we can do more quickly.

Neko had just put out her first record in '97. She seemed really popular to us even though she wasn't. She already seemed like a big deal. I remember touring with her in like '99 and 2000,

and there would be maybe 100 or 200 people at the shows, and thinking, "She's huge. She's so popular." 'Cause I was used to going on tour and there was nobody there. I was used to going on tour where 50 people at your show was the biggest show of the tour. So I couldn't get over how big she was. But now I look back and I think, "She was pretty small at that point." But it seemed big to us.

This seems like another one where the narrative doesn't matter much.

NEWMAN: It was very much, like, a breakup song. It was kind of an "F you." It was written in sort of a circuitous way as an "F you" to a girlfriend. "For the love of a God you sang, not a letter from an occupant" -- like trying to say, "You just didn't like the fact that I was human. You couldn't deal with the fact that I was flawed. So fuck you." Who sang "Fuck You"? Who did

it? Cee-Lo Green. It was kind of a second cousin to "Fuck You" by Cee-Lo Green.

7. "To Wild Homes"

NEWMAN: Dan would just make so many demos. I wish I still had the cassette. I swear he gave me an hour-and-a-half-long tape that was just him singing songs or pieces of songs. And I just listened to it, all these endless Dan songs. And some of them were very tossed-off. And I'd just find the ones that I thought were really good. So by doing that I found "To Wild Homes" and I found "Execution Day, and maybe another one but I forget what it was.

That was a really early song. It would have been on our first cassette, but we just didn't nail it. We recorded "To Wild Homes" way back when we did all the first songs, but something about the performance -- I think we hadn't arranged it yet. It just didn't work. Once again we did that trick where we broke the song down. There's a point where the song breaks down and just becomes an acoustic, which in my head it was a tribute to "Space Oddity" where it breaks down and is acoustic. I might have said that when we were arranging it, "What if it breaks down, kind of like 'Space Oddity' here?" Then that worked.

I remember listening to this one in the studio and thinking, "We're good." This was a song where I thought, "Something's going on here that is unusually good." I just had a moment of focus. I had a moment of clarity where I could hear us for what we were. And I thought, "We're good. We're really good." It's like my brain took a snapshot. I can remember where I was sitting in Rodney Graham's studio when I thought that. Back in early 2000 I was listening to "To Wild Homes" and thinking, "We rule." So I treasure those moments, those rare moments.

8. "The Body Says No"

NEWMAN: This one, I started writing it back in my old band Zumpano. There were parts of it that I think I initially thought could be a Zumpano song, but I just kind of sat on it for a few years. Which I do -- sometimes I have a little piece of good music and I think, "I've got to find a good place for it." Sometimes I just sit on it for a while until I figure out a place for it to go. But I think that chorus, "Man, can you believe she didn't need me/ Any more than I needed..." I feel like I had that back in Zumpano. I just had to kind of rewrite it.

We have to play these songs in less than three weeks. Now I'm thinking, "Oh shit. How does that one go?" It's a lot of work.

So you haven't gotten to rehearse for the tour yet?

NEWMAN: We're just trying to learn them on tour. The cramming basically has to come in the week before the shows. I mean, a lot of them we know. A lot of them I could basically do in my sleep. "Mass Romantic," "Fake Headlines," "Slow Descent," "Jackie," "Letter From An Occupant" we've played so much. Songs like "Body Says No" we haven't played in a long time. Those are the ones where you have to teach yourself the song again. And the songs have a lot of twists and turns. We made our life needlessly difficult.

That's part of the appeal of the songs is all the twists and turns.

NEWMAN: Yeah, I guess that's true. Sometimes I listen to old songs and I honestly don't know where they're going. And that's an interesting feeling. A song I wrote, the bridge will come and I will think, "I don't remember writing that whatsoever. I don't remember singing it. I don't remember playing it." And I think that's cool. It means you can listen to your own music like a fan. So hopefully I have that feeling when I listen to "Body Says No." Hopefully I'll listen to it and go, "Wow! Cool."

That's one of those songs where it already has one chorus and then you break out into another chorus. I like songs like that, like "Some Might Say" by Oasis.

NEWMAN: The fake-out chorus! I've always loved that stuff. And even in the band, there's never been any agreement on what's a chorus. Somebody'll be like, "That's the chorus." My response is, "Sure, whatever you want. Why do you have to call it anything?" When you start moving away from simple verse chorus verse chorus structures, why even bother labeling it? It's funny -- I enjoyed writing like that, but it didn't take me long to not want to write like that anymore. A few years later I felt like it was becoming like a cliché, like the way my songs would go in these weird directions, kind of asymmetrical. I found myself just wanting to write simpler songs. 'Cause I thought, "I've done that." I've already written "Bleeding Heart Show." I don't want to write it again.

I was just listening to [Newman's 2004 solo debut] The Slow Wonder today. It seems like you were starting to streamline by then.

NEWMAN: Yeah, definitely. Those were songs that I thought were not Pornographers songs, and it's probably because they were a little straighter. I was at a point where I thought, "The Pornographers need to sound like that." And then after Slow Wonder, when that got a really good reaction, I went into Twin Cinema thinking, "Maybe we can sound whatever we feel like. Maybe we don't have to have a formula." So then we started playing mellower songs and stranger songs. And then on Challengers we had songs that are basically acoustic. I think I always wanted to mess around with the formula, which maybe was not the most brilliant business move. When other bands are just trying to perfect their style, I was trying to abandon it. I thought, "No, I don't want to write more songs that sound like our other more popular songs. I want to do different songs."

9. "Execution Day"

NEWMAN: I think it was the first song where we nailed the Pornographers outro. You know the way it just changes gears and changes into that, "On! This!" [Mimics guitar riff.] When I was playing that guitar line, I was trying to do something like "All The Young Dudes," you know, Mott The Hoople. The "All The Young Dudes" line was [mimics slightly different guitar riff]. It was a different version of that. It was an example of things that I thought were obvious.

There are various spots on this record where I threw things in that I thought were such obvious nods to other records, and no one ever spotted them. Like no one ever listened to that guitar at the end of "Execution Day" and said, "Oh, he's trying to do a Mott The Hoople 'All The Young Dudes' thing!" Similarly, on the outro to "Wild Homes," there's a high countermelody. Neko and Dan are singing, "To wild homes we go, to wild homes we return!" And over top of it, I sang, [in falsetto] "Toooo wild homes!" Which I lifted almost verbatim from a Fleetwood Mac song. It was "I Know I'm Not Wrong" from Tusk. I thought, "Oh, this is so obvious." And no one ever spotted it.

I always thought that was interesting. Like, oh, you can get away with a lot in this world and no one will ever spot it. Thought the years, people have said, "You guys remind me of something, but I can't figure out what." I've always taken that as a great compliment. Because I think that's what we're trying to do. We're trying to sound alternately familiar and alien almost all at the same time.

10. "Centre For Holy Wars"

NEWMAN: Our first ever show was '98 or '99, and it was at the Good Jacket. Remember I talked about the used clothing store that put out the compilation? They were a small little space, and they would move the clothing racks and have little indie shows. And that was our first ever show. After we played, there was a guy DJing, and he played "Son Of My Father" by Giorgio Moroder. I'd never heard it before, and I thought, "This is the greatest song I've ever heard in my life." Almost immediately then I thought, "We need a song like that." And that was "Centre For Holy Wars."

Listening back to it, it's so obvious that I was trying to sing like Sparks. The melody has that very [sings the melody] -- it has that kind of arch Sparks quality. To me it seems obvious. Whatever I thought I was thinking, that I was trying to do something like "Son Of My Father." I was trying to give it kind of a Sparks vibe in the melody. That was "Centre For Holy Wars."

I was also really into Lilys. I love Better Can't Make Your Life Better and The Three Way. I think there's something about his -- he was doing something that was clearly indebted to the Kinks, but he was doing his own new thing with it. And melodically it feels not that distant from Sparks. I think that's why I bring it up. I think they were part of the mishmash of influences that definitely became the first record.

Was this one topical at all?

NEWMAN: It became topical. But we finished it a year before 9/11. That's a weird thing about this record, like "Centre For Holy Wars" and "Fake Headlines," they all kind of feel like they were predicting the future of America. Especially "Centre For Holy Wars." I read the lyrics, and I think, "If I wasn't writing about 9/11, what the hell is it about?" So much of it feels like: "Floating in the air at the centre for holy wars, I hope it never comes down again"? It just feels like I was writing about 9/11 before it happened. But I wasn't. I don't know. Maybe I'm psychic. There's something about falling and floating that's always been in my subconscious. Like "Fake Headlines," the second verse is something about falling and floating. I don't know why that is. I might have to go to a therapist.

11. "The Mary Martin Show"

NEWMAN: That was the final song on the record. That one felt pretty tossed together to me. I feel like we recorded it very quickly. I'm not sure anybody else sang backup on it. If there's any backups, I think it's me just singing with myself. We brought in this guy named Davidian Chorley to play saxophone. I guess I got it in my head, "I want saxophone on a song." We were getting to the end of the record, and I thought, "How about this new one?"

I remember when I was writing this one, I really loved the melody. There's that part where it goes, "To aim far too, far too low." When I was writing that, I remember thinking, "This is the best melody I have ever written."

Some of the songs were sitting around for two years. Some of them we recorded them and it didn't work and we recorded them again a year later. But that one we did last, and we knocked it out pretty quickly. Maybe I felt like we needed one more song on the record, so that was "Mary Martin Show."

What got you thinking about Mary Martin?

NEWMAN: I think it was about a girl I knew. Kind of a pixie-ish girl. I don't remember. It didn't matter. It's like what is "Jet" about? It just is. What is McCartney talking about when he says, "Ah, mater, want Jet to always love me"? It doesn't fucking matter. It's just cool.

12. "Breakin' The Law"

NEWMAN: "Breakin' The Law" might have been the song that kind of put the Pornographers together. I remember it was on the first Destroyer record, We'll Build Them A Golden Bridge, and I saw him play around that time, around 1996 or '97. And he did that song, he did "Breakin' The Law." I had this sense that I'd never seen a friend of mine play such a good song. 'Cause everybody sees their friends play and you're like, "My friend's band is cool. I like my friend's band." This is the first time I thought, "This is world-class. Some of what Bejar's doing is absolutely world-class." And I think I got it into my head that maybe I should do something with Bejar because he's really good. And of course, that song might have been the first song on the list. Like, "OK, we're gonna do 'Breakin' The Law.'" That might have been song one for the New Pornographers.

That one was fun. We were in the Carswells' basement. I remember recording the vocals for that and we were just winging it. There's a point halfway through where the vocals come in, and it was just Dan and I around the microphone, and we were doing random takes, not listening to the other takes. We were just winging it. Like, we knew the words but we were just making up harmonies -- singing along making up harmonies but not really thinking if they fit. And we just listened to them all together and they just accidentally fit. And then we did the big gang vocal at the end, which was fun.

That's one of those moments I remember from early Pornographers times where it just felt fun. It just felt kind of joyous and strange. We were probably just sitting around a microphone holding gin and tonics. I always loved the way that one came out. We put a gong in there. We had a sound effects record that had a gong on it, so we put a gong in there, which just seemed hilarious to us. Like a hilariously over-the-top move. Like, "How about we have a gong? A gong goes off and then it turns into a gang vocal?" It's an example of how we thought, "Who cares?" If we thought it was kind of funny and cool, we would do it. Because it was for us. We didn't know it was for the world. Or not the world. But we didn't know there would one day be a few hundred thousand people that know the record.

The Mass Romantic reissue is out 12/10 on Matador. The New Pornographers play Seattle tonight and tomorrow and Vancouver this Saturday and Sunday.