We’ve Got A File On You features interviews in which artists share the stories behind the extracurricular activities that dot their careers: acting gigs, guest appearances, random internet ephemera, etc.

Just over 40 years ago, childhood friends Roland Orzabal and Curt Smith formed a band called Tears For Fears. You know what happened next. The duo released a trio of '80s albums that made them one of the most iconic artists to emerge in that decade, with a series of indelible pop hits that were themselves something of a Trojan horse for albums that were darker, weirder, and more complex than might be expected. Even if the story had stopped there, Tears For Fears' influence would've been solidified.

At one point, it did almost stop there. Smith left Tears For Fears in the early '90s, and Orzabal carried on with the moniker as a solo project. Smith spent some years away, figuring out his life and starting new projects and acting every now and then. Then the two got back together in the beginning of this century, eventually releasing a reunion album fittingly, winkingly titled Everybody Loves A Happy Ending.

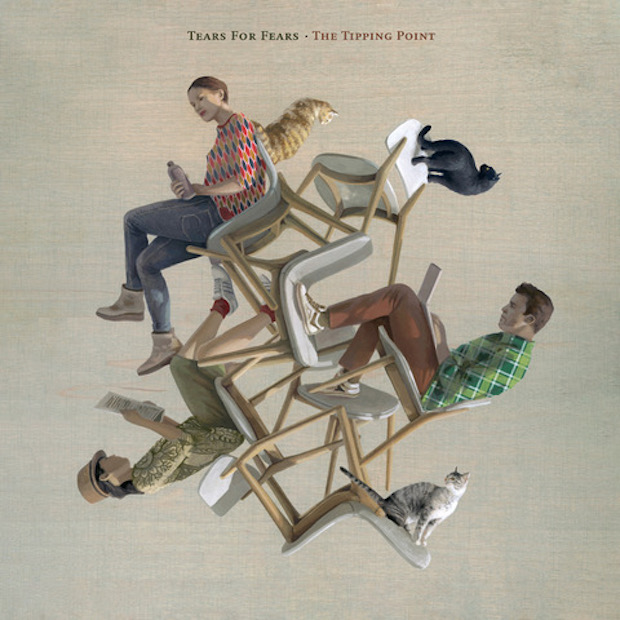

That album arrived over 17 years ago in September of 2004. There are a lot of reasons Tears For Fears didn't release another album in all that time, but now that's about to change. Next month, Smith and Orzabal are once more returning with a collection called The Tipping Point. In the interim, Tears For Fears have evolved as a live band, but they've also had multiple recurrences in pop culture that has reframed their legacy -- not just beloved '80s hitmakers, but adventurous songwriters who have woven through the years at their own pace and according only to their own muse.

Ahead of The Tipping Point's release, we caught up with Smith, calling via Zoom from his home in Los Angeles. We talked about the new album, and all sorts of other odds and ends from across the years.

The Tipping Point (2022)

Obviously it’s been a while between releases. How long was the actual gestation of the album? Was this a process through all those years or something that was started and ended a few times?

CURT SMITH: It was pretty arduous, looking back on it. I’ve also been qualifying it by saying without that part that didn’t work, the arduous part, we probably never would’ve gotten to where we did. In that sense, I think it was necessary to a certain degree. The actual process really started about seven years ago. If you go back 17 years, since the time of the last album, we’ve been playing live every year consistently and actually getting much better at what we do live. We didn’t feel the need to go record new material at that point in time.

Outside of touring, our primary concern was our families. My children were younger then. The last album we released before this one was released on my oldest daughter’s fourth birthday. She’s now 22. [Laughs] That tells you something. The importance of being a present parent was more prime in our minds at that point in time. We didn’t have any intention of spending most of our time away, being on tour too much. Even when we were touring, I never spent more than two weeks away from my children. It was always a conscious thought and desire to be there for them. I think even more than Roland, because my wife works. One of us always has to be around. Juggling the two was very hard for me, but it was important.

About seven or eight years ago, we got to the point of being on tour where we were getting a little bored of doing the same songs all the time. I think it was at that point where we sat down and thought, Wouldn’t it be nice to introduce some new songs at some point? We didn’t want to put in cover songs or anything like that, so we thought it might be nice to write some more. We sat down with our then-management to discuss the way to do that and go ahead with the recording process.

The decision was arrived at that we should maybe try doing these songwriting sessions with some more modern producers. I’d say it came primarily from our management but we weren’t in disagreement. We went along with the process. That was the arduous part. We did all these sort of speed-dating sessions with hit songwriters du jour. We did them sporadically. It’s not like we did months of it. We did them a few weeks at a time. Over the years we ended up with this record -- probably in 2017 we finished what could’ve ostensibly been an album.

Oh, so there was a whole album that came out of those sessions?

SMITH: Yeah, there could’ve been a record. They were all finished and mixed. I just didn’t feel it was that good. I didn’t think it was representative of us. I don’t want to use the words "desperate attempt," but ... just an attempt to become modern and I didn’t see the point in it. I didn’t think it had the depths of normal Tears For Fears albums, the meaning, the lyrical content. I could go on and on. The production, it was all just kind of one level. Lots of attempts at making a modern hit single. And I ended up hating it. [Laughs]

There was a lot of business stuff going on in the background here, because we were with Warner Bros. at the time and they were going to release it and I didn’t like it. In the end we decided to buy it from Warner Bros. and we were going to sell it to Universal, but then that fell through thankfully because I still didn’t like the record. So myself and Roland eventually got together and said, "Well, how do we forge a way forward?" We got to that point of, "We started, so we should finish."

We went through all the old tracks, and there were five we could agree on that were good songs. They weren’t the recordings we’d end up using, but they were really good songs that we didn’t want to lose and we wanted to be a part of a new project. We set about trying to find the other half of the album. Our first decision as to go the completely opposite route of the way we’d been going. Instead of sitting in a room with some modern songwriter, or even another songwriter, for the first time since we were 18 we got together in my house with two acoustic guitars. Let’s see what comes of this. We’ve tried all of that, let’s see what comes of this.

And that’s what gave you "No Small Thing"?

SMITH: That’s what gave us "No Small Thing," the opening track of the album. It sounded completely different. It started with an acoustic guitar, it could’ve been a Johnny Cash song at that point. Then we took it away and we made it into ... it ends up being grandiose and huge, elements of Led Zeppelin and orchestra. We had a blast doing it. That’s when we realized, A) this is what we’re good at, and B) the album should be a journey. It should have highs and lows. We had it in that one song, but the journey in that one song was literally a ramp that went from acoustic guitar to mayhem.

The album should have those light moments, those dark moments, those intense moments, upbeat moments. We set about fixing the old five songs and writing more and finding more songs that would fit into this journey we intended to make. That process started in about 2020, the writing of "No Small Thing." Because of the pandemic, we didn’t get to go into the studio until September of 2020, and we were done by Christmas.

After all that time, then it was done relatively quickly.

SMITH: The recording process to finish this album was literally three months.

The title track and the title of the album -- obviously the last few years have felt like tenuous times. But The Tipping Point refers to personal things as well, right?

SMITH: The Tipping Point works on many levels, which is why we chose it as the title of the album. "The Tipping Point" the song is, itself, about Roland unfortunately watching his then-wife pass away. In that sense, it was about a very personal tipping point. It was about when do you let someone go. When do you know they’ve gone? Is it when they actually die physically? Or have you lost them before that, when they’ve given up? It’s about that tipping point and questioning when that is, when do you let go?

As you mentioned, there were many other tipping points. Socially, politically, ecologically. We were all going through that and we will be for a while. The pandemic, the Black Lives Matter movement, the Me Too movement. We had Trump in power. We had the January 6th insurrection -- they attempted a coup here, effectively. Not to mention climate change. Let’s throw that in there as well. We are at a major tipping point. It wasn’t just politically in America. The rise of the right wing worldwide and the tendency towards dictatorships worldwide was a concern.

Sometimes I've seen people say these recent years were reminiscent of the Reagan/Thatcher era, and this happens to coincide with the resurgence of certain musical styles from that time. Not that Tears For Fears were explicitly political in the past, but in terms of working in the early ‘80s and more recently, do you feel parallels between these eras?

SMITH: I do. I think it’s worse now, having unfortunately been through both. The Reagan/Thatcher years were the beginning of our career. "Everybody Wants To Rule The World" was definitely influenced by those years. It wasn’t always quite as serious. Nobody invaded the government. Nobody tried to shut it down. They didn’t try to stifle people’s voices. We ended up getting both out and it was a peaceful transition of power. There was plenty of anger back then. But [recently] you had, in America, a leader who was encouraging that anger. He was basically making it bigger.

I hate to get overly political, but it’s interesting the right-wing governments in the western world are, really, primarily, England, the US, Australia. What do those three places have in common? They have Fox News, or Sky News. Rupert Murdoch-run news companies. That’s a concern -- where media’s now being manipulated, and it’s so easy to do. That’s a bigger concern now than it was in the Reagan/Thatcher years, because you really did have an independent news. It wasn’t biased one way or the other, normally. The news, in general, was believed by people. I think that kind of helped.

Now you have huge media conglomerates, or certainly one in particular that is stoking the fire rather than helping people rationalize and be objective about what is going on. There is no objectivity left anymore in the news realm, or certainly not much. The only way you can balance out that one news network that is so biased, is to become slightly biased yourself the other way. It’s a difficult time. I don’t know the way out of it. Hopefully when the hierarchy at certain news companies passes on, the next generation won’t be so fervent in their support of what are effectively dictatorial tendencies.

Graduate (Late ‘70s/Early ‘80s)

You and Roland were in this band before Tears For Fears. What did you learn from that project that helped shape what Tears For Fears would become?

SMITH: As is the case with a lot of things in life, before you can find out what it is you want to do, you learn what it is you don’t want to do. [Laughs] We were young and we were writing little cute pop songs. They didn’t have that much depth back then, because we were kids. We were probably thinking about one thing, as 16 or 17 year old boys do -- girls. Being in a band was one of the best ways to meet girls. So, we were in a band.

It was average, to say the least, the band. The songs had their redeeming bits. They certainly were melodic, so we were good at melody back then. But the other three members were really into playing live and getting out there and partying and all those things. We went on a three week tour, I think it was, of Germany. In two vans, humping our own gear, playing clubs to sometimes eight people. By the end of it, myself and Roland sat down in a hotel room in Holland somewhere and we were kind of in tears. We were like, "This is not what we want to do, this is dreadful." It’s too much like hard work, for one. And no returns. The idea of us doing that when we were 40 would be weird, and we were trying to look to having a career doing this.

That was the point we realized we wanted to really hone our craft as far as recording artists went. We wanted to get better at our art, we didn’t want to just go out and play. It was also at the point that certain albums came along that really influenced our views on recording. I want to say it was ’79, ’80 — Remain In Light by Talking Heads, Peter Gabriel’s third album, David Bowie’s Scary Monsters, David Byrne and Brian Eno’s My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts. All in this one period of time. They were all amazingly interesting productions and they were very different for their time, to me.

We sat down and listened to these records and we decided, "We want to get that good." Whether we could is one thing. That would be a question. I don’t think we’ve ever attained something that’s that good. But that was our driving force. We decided to leave [Graduate] because they didn’t agree with us. Playing live was the way to go for them and we wanted to be in the studio. That’s when we decided to form Tears For Fears.

Michael Andrews And Gary Jules' "Mad World" Cover In Donnie Darko (2001)

Obviously there is a very famous cover of "Mad World" used in Donnie Darko. At least how I perceive it, there was a reclamation of the ‘80s around that time and that’s never really gone away since. Did you feel something yourself in that moment?

SMITH: Well, not really at the time I don’t think. I remember I first heard the Gary Jules and Michael Andrews version of "Mad World" on KCRW in LA. I thought it was Michael Stipe. It was only afterwards I discovered what it was, and then I ended up watching the film. I think the more powerful use of our music in that film is actually "Head Over Heels." But it did become a kind of hit, that [cover] song. In England, that version of "Mad World" became #1, around Christmastime. Which tells you something about the English. Weirdly, our version of it only got to #3 but it was also at Christmastime. That’s the only time one of our songs has been #1 on a singles chart in England, and it wasn’t ours.

But it did start a new appreciation I think. I don’t think that effected us as much… I mean, we didn’t see the effect as much as, say, Kanye sampling us or Lorde doing "Everybody Wants To Rule The World" for Hunger Games. They seemed to have more of an effect on how hip we were. Coming up to the modern day, streaming services have had more of an effect of us. If you’re listening to, say, a 1975 record -- because they’ve cited us as an influence, you’ll get recommended our music. These things do give us new audience, because they’re recommended to us and people find us that way.

We only noticed it in the last couple years, when we played Bonnaroo — which is ostensibly a far younger festival. We expected maybe a thousand people if we were lucky, and it was stretched past the tent overhang and went all the way back. I’m looking at the front of the audience and they’re all far younger than me and they’re all singing all the lyrics to every song from The Hurting. It was shocking to me. When you look at it retrospectively, it makes sense, because we wrote it when we were that age. Those lyrics resonate with a younger audience. But that was when I noticed a shift, when we started playing festivals and noticed there was a younger audience we were gaining in America.

Kanye West Interpolating "Memories Fade" (2008), The Weeknd Sampling "Pale Shelter" Alongside The Romantics’ "Talking In Your Sleep" (2017), Drake Sampling "Ideas As Opiates" (2009)

What has it been like to hear your music recontextualized in various rap and pop songs over the years?

SMITH: It’s great. Not only are you multi-generational then, but without getting too business-y, you’re multi-format. It’s never a bad thing. I always think, if people repurpose what we do, then I’m kind of fine with it. I find it interesting to hear someone else’s interpretation of what we do. It’s when someone copies what you’ve done and tries to do what you did, it’s sort of boring. It’s like doing a straight-up cover version in that sense. It’s not that interesting. What was interesting to me about the Weeknd and Kanye, they both sampled songs from The Hurting, not Songs From The Big Chair. That was the big album; The Hurting wasn’t big in America at all. It was in LA and New York, but it didn’t even break into the top 75 as an album here. I guess they do their homework.

Again, with Lorde and Gary Jules and Michael Andrews -- they’re reimagined versions. Strangely, their recordings are more in tune with the actual lyrics. I don’t think we necessarily realized we have this habit of couching what are quite heavy lyrics with more uptempo and catchy backing tracks. I don’t think it was ever a conscious effort. Those tracks made us realize, "Oh, yeah, that’s what we do."

Have you met any of these younger stars after they’d cited your music?

SMITH: I met Lorde. I’ve not met Kanye... I don’t get out that much, I have to say. Weezer also covered us, but we performed with them. As far as people who cite us as influences, the only one that comes to mind is the 1975. When they played at Coachella, I had a long talk with Matty [Healy], and we’ve met a few times since. I’ve been to a few shows. I’ve become a big fan of that band. I see in them a modern day us, in an interesting way. They’re a lot deeper than people maybe give them credit for. They make pop music, but you listen to an album and they make albums. It is an album. I do appreciate that.

Tears For Fears Covering Arcade Fire, Hot Chip, And Animal Collective (2013)

Some years ago you released covers of younger bands, some that could theoretically be influenced by Tears For Fears. I was curious what the process was to pick those particular songs. Or, similar to what we were just saying about the 1975, how hungry you remain to find new artists out there.

SMITH: You’re always interested in modern music. Whatever may be current. The difficulty is sifting through all the average stuff to get to the good stuff. But that was always the case. There’s a lot more out there now, so in that sense you’d think it’s slightly harder, but because it’s streaming you have everything at your fingertips. When I was growing up, you had to go into a record store and go into a booth and put the record on. There was a certain joy in that, but now I can look it up on my phone — you tell me a band I may not have heard of, I can listen to it in 15 seconds.

As far as choosing those songs, there was a Record Store Day coming up and we were asked if we’d like to participate in any way, shape, or form. I do love vinyl, so helping on Record Store Day was a positive thing to do. We had no new material of our own at that point of time. So you could do cover versions, but picking cover versions of our era was dull. As we’ve discussed, there were a lot of younger musicians who were sampling us or covering us, so we basically just thought we’d return the favor. That was the simple idea behind it. We went surfing around to find songs that spoke to us, and those were the ones that spoke to us.

Going back to the 1975, that seems particularly special in that you actually feel they are kindred spirits. Are there any other younger artists you feel that level of connection with?

SMITH: I don’t know. When I went to see Twenty One Pilots live I did. I wasn’t necessarily the hugest fan of their latest work, but maybe I haven’t given it enough time to grow on me, I don’t know. Also, I don’t have to be a fan of every thing someone produces -- I wasn’t a fan of every David Bowie album. What is more gratifying to me in knowing I’m doing the right thing as far as choosing this as my profession is when I hear an album and I go, "God, I want to be that good." By someone younger than me. The album I would cite in that sense is Bon Iver’s i, i. When you listen to an album and go "Oh my god, I’ll never be this good." That’s good. That’s healthy. If you get to a point where you think you’re better than everywhere else, you need to stop. Because A) you’re wrong, and B) you’re delusional.

Recurring Appearances In Psych (2010-2021)

You’ve appeared in Psych several times, and they kind of put you through the ringer. You’re shot in one episode, you’re eaten by zombies in another.

SMITH: It’s however they can abuse me. It goes to the next level each time I do a guest appearance. It all started when James Roday, who’s Shawn Spencer in the TV show but is also one of the writers, came to one of our shows. He’s a big Tears For Fears fan. He managed to get backstage -- I don’t know how -- and was like, "You’ve gotta come be on our show." I’m like, "Who is this guy?" I didn’t know anything about Psych. I’m not an avid TV watcher particularly aside from certain genres. I went and looked at it afterwards and thought it was pretty amusing, and it’s referential of a certain era. I thought, why not, it’ll be a chance to do something new.

I filmed the first episode, which was me effectively being held hostage even though I was being paid for it, being told to sing on cue by a billionaire. Shawn Spencer in the TV show is a huge fan and is like "Oh my god." What happens with that group of people -- you can speak to any extras, because there are tons of recurring characters on Psych. Once you get sucked in, you enjoy it. They are the nicest bunch of people to work with. They really are like a family. They adore each other. Once you’re a part of it, when they call again and say, "Can you come do another one?" you’re like "Yeah, sure, this is going to be fun."

And every time they were like, "Do you mind if we abuse you this much? We’re going to step it up." As you say, I was shot and mauled by a panther and then I was turned into a zombie. The biggest insult of all was the latest movie. They forced me, in the script, to reform with Andrew Ridgeley as a new Wham! That’s the highest level of abuse you can get.

Worse than getting turned into a zombie?

SMITH: Oh, absolutely. No question. I’m sure James and Steve Franks, who created the show, thought, "How can we just abuse him even more?" Including the really bad ‘80s music video that went with the song they wrote specifically for me to sing.

You had kind of dabbled in acting a bit in the ‘90s.

SMITH: Yeah, but always with friends. I enjoy it, I do. I don’t go out fighting for it, but I enjoy it when it comes along. The Psych thing is easier because one, I’m playing myself, so it’s not a big stretch. There was definitely some kind of acting in it because I wouldn’t join Wham! with Andrew. [Laughs] Maybe it’s far better method acting than I think.

Leaving Tears For Fears And Starting New Projects (‘90s)

I kind of have this perception that the transition from the ‘80s to the ‘90s seems like one of the hardest cuts in pop history. The idea there’s all this new synthesizer music, and then in the ‘90s it’s all these more guitar-oriented bands, then the ‘80s weren't reclaimed again until the ‘00s. Similar to when we were talking about Donnie Darko, did you feel that in your own life in the ‘90s? As in, was there a strange searching period after leaving Tears For Fears?

SMITH: Strangely, for me, the ‘90s were one of the most enjoyable parts of my life. It all depends on your personal circumstances. The reason I left Tears For Fears was fame didn’t sit well with me. I wasn’t enjoying it. My personal life in the UK fell apart. I was married before, went through a divorce. Myself and Roland weren’t getting along, because we had to grow up together as famous people, which is horrible. I decided to leave the band and move to New York, where I met my new wife, and we’ve now been together about 35 years.

My 10 years in New York were undoubtedly, without question, one of the most enjoyable times in my life. The freedom I felt. If you’re famous in England, people tend to follow you around — certainly when you come from a small city like Bath, you’re the most famous person who lives there. People in New York look at fame with a certain disdain. I’ve never been stopped in the street in New York. People don’t notice you, or they know who you are but they would never accost you. That freedom and that chance to just be a normal person is just fantastic.

I did discover music was still a big driving force in my life. Originally I had this syndicated college radio show I hosted, and I was interviewing younger bands or younger bands came in and played live. They ranged from bands like the Meat Puppets to Black Sheep. It was fantastic, and reassuring, that I still loved music that much. I did VJ on MTV for a bit as well -- that was a bit more corporate, so it wasn’t as enjoyable as the college show. Sort of halfway through that decade in New York, I started meeting Charlton Pettus, who still works with Tears For Fears now. He dragged me sort of kicking and screaming into his apartment to write songs. I say that facetiously, but it wasn’t something I was thinking of. He was like, "What are you doing? You should be writing, you should be singing."

So we wrote a bunch of songs and it was fun so I formed this band Mayfield. It wasn’t my own name, it wasn’t a "Mayfield featuring..." It was just Mayfield, the joke being "Curt Is Mayfield." We played clubs, and the only criteria was they had to be within walking distance of my apartment. We played the Mercury Lounge, Brownie’s, CBGB’s, Arlene’s Grocery. I had forgotten the fun aspect of playing. By the end of the ‘80s, that had been kicked out of me, because it just becomes a business. I’d lost that passion for it. That’s what New York gave me back, between the radio show and forming a band under the radar. It’s what I was missing in the end of my initial time in Tears For Fears.

"The Hurting" Being Sampled In "Do They Know It’s Christmas?" (1984)

I had no idea "The Hurting" was sampled in this, it kind of blew my mind.

SMITH: It’s the drum intro, it’s half speed. You wouldn’t hear it as "The Hurting," but it’s a slowed down version of the drum into to "The Hurting."

Did you know that was coming?

SMITH: How did we feel about not doing it?

Right like, you’re not on the song but you’re on the song.

SMITH: We didn’t know until afterwards what Midge [Ure] had done with the drum sample. We ended up being on it without being on it. It was fine. It was the best of both worlds. We contributed, but we didn’t have to do anything. [Laughs] All those sort of group things, we tend to shy away from them. And also Bob [Geldof] wasn’t the best. Having said that, I guess he did a great job because he got so many people to do it. But Bob didn't go about it the right way half the time. The initial argument we had about Live Aid a few years later was, Bob announced we were playing Live Aid without even asking us. It’s like, who does that? You know?

It was at a point in this yearlong tour, it was the only week off we had. It was a hard decision. One, I was pissed at Geldof. But we sat down and said let’s be objective about this: Is it going to make more money for the charity? Which was the important bit. We came to the conclusion it wouldn’t matter if we played or not. There were enough people doing it. The only thing it would do would benefit us, and we wanted a week off, so we didn’t do it. We knew it wasn’t going to be detrimental to them.

"Everybody Wants To Rule The World" (1985)

There’s something I’ve always wanted to know about this song. I’ve read online it was supposedly inspired by the bassline from the Simple Minds song "Waterfront." Is that true?

SMITH: It was somewhere between that... "Boys Of Summer" more.

Really?

SMITH: I think. We go back and I remember the conversations, they’re not necessarily planned. We were at the end of doing Songs From The Big Chair and we were missing a song. When I go back to how we made this new album, making a journey... we were missing what was a more light-hearted moment. We had "Shout," which was in your face. We had "Head Over Heels," which was also pretty brash even though melodic. We wanted something that wasn’t so dense musically. If you look at the recording of "Everybody Wants To Rule The World," it’s the least amount of tracks we ever used on a recording. There really isn’t much on it, it just goes together well.

It had a shuffle beat, which we loved. We were thinking "American driving song." That’s where the "Boys Of Summer" bit comes in. It was the rhythm that sold us on it. At the time, we didn’t think it was a hit record at all. We just thought it was part of the journey on the album, that it fit what we needed -- something lighter, breezy. Imagine yourself in an open top car. That’s the video in the end, but that’s what we were missing on the album -- that moment where you feel free. Again, lyrically, that’s not what it’s saying at all. But rhythmically and musically that’s what it is.

Songs From The Big Chair is a big favorite of mine, that I was getting into around the same time I was getting into some of your influences -- those Peter Gabriel solo albums, those Blue Nile albums. Growing up, "Everybody Wants To Rule The World" or "Head Over Heels" were just in the atmosphere. It took getting into it for myself to realize it was a much more complex album -- not just a couple standalone hits. When you were working on that album, did you feel a part of what was going on in the ‘80s, with the new wave moment or whatever? It’s related to its surroundings but was doing something that felt very different too.

SMITH: I think we’re always trying to make something slightly different. If you go back to when "Mad World" came out, nothing was sounding like that back then. You’re always trying to do something that’s slightly out there, but if it clicks with the time, then that’s just an accident. We’ve never been part of a scene or a movement. We’ve never even been fashionable, to be honest. I think in the long run that’s worked to our benefit even though that wasn’t a conscious attempt. I think it’s part and parcel with us being two guys from this small city.

That continues today. You’re normally a part of the London scene, or Manchester, or Glasgow. But there was no real scene in Bath. There was one club that had everyone from us to King Crimson playing in it. It was one club, that’s all it was, and it didn’t play one genre of music. There was no Hacienda. We’ve never consciously tried to be part of a movement. I find the idea slightly alien, but that’s because I’ve never been part of one.

The Tipping Point is out 2/25 via Concord Records.