We’ve Got A File On You features interviews in which artists share the stories behind the extracurricular activities that dot their careers: acting gigs, guest appearances, random internet ephemera, etc.

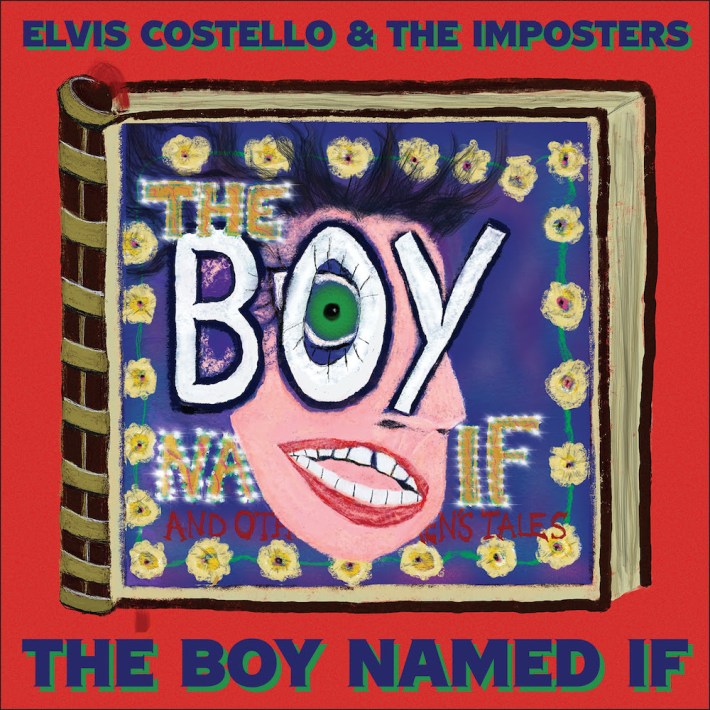

Earlier this month, Elvis Costello released The Boy Named If, his 32nd studio album. Oftentimes raw and bracing and tapping into a core strain of Costello's songwriting, The Boy Named If looks all the way back to childhood, to imaginary friends and the excuses we make for our own bad behavior. This being Costello, he twists and complicates that premise, carrying it forward through more adult misdeeds and the eventual reckonings, perhaps even decades on, that prompt someone to grapple with exactly what growing up looks like.

With a career that now stretches well beyond 40 years, Elvis Costello knows something about different lives, and the discrete chapters we live within them. Aside from his influential run of early albums, he's also produced '70s and '80s peers, collaborated with heroes from Paul McCartney to Burt Bacharach, guested on a whole bunch of TV shows, and even filled in for Letterman once. Just the fact he has 32 albums to his name is daunting, but the list of his extracurriculars and other projects is truly staggering.

On the occasion of The Boy Named If, we called Costello up via Zoom to talk about some of those odds and ends from across his career. The other thing about him: He's quite a storyteller. One topic leads to half a dozen, with connections that span decades. There was so much more we could have asked him about, and the list we did get to is still a dizzying zig-zag across the years. Read our conversation below.

The Boy Named If (2022)

The name of the album comes from the idea of an imaginary friend, and this sort of innocence that gets complicated and lost over the course of the songs. What led you to writing about the past in that way?

ELVIS COSTELLO: I don’t really know where it comes from. It’s very tempting for people to go, "Well, you were working on Spanish Model so maybe hearing that rock ’n’ roll music again..." No, we’d finished that record. I’d made a record with some very weird-sounding rock 'n' roll on it, but it wasn’t played with the band. We were on tour when everything started to go into chaos. We could see the approaching crisis. The last couple nights, friends of mine were staying home, saying, "I don’t know whether I want to come to a theater." So, I’d better take the responsible view because the government wasn’t doing anything in England, and cancel the rest of our dates. Suddenly I’m back with my family in Canada, going, "Where did the world go?" I was in mid-stride, literally. I went into the wings at the last show in London and said, “Hey guys, let’s play 'Hurry Down Doomsday (The Bugs Are Takin' Over),' a song from 1991. 'It’ll be funny.'" It wasn’t very funny a couple weeks later, was it? [Laughs]

So anyway, I finished off the record I’d been working on, Hey Clockface. I suppose I wrote very quickly with a guitar in my hand. Because I’d been working on some very piano-based, melancholic ballads in Paris, it’s just a natural thing to want to do something different and lift your spirits, particularly given I was outside in the garden with my guitar. Before I knew it, everything was picking up tempo, everything was major keys for the most part initially. By the summer of 2020, Pete Thomas said, "Well, it doesn't look like we’re going back to work." Our job is really playing music onstage. Nobody's making a living from making records, I don't think, unless you're called Adele or Taylor Swift.

So, why not make a record? Let’s keep connected. I’ve got these songs, and the minute I send them to Pete he sends them straight back to me with the drums on it. I thought, "That sounds great, let's just keep going." It's as simple as that. For all the reasons you’d do it when you were a kid. It was playful in that sense. Before we knew it, we’d gone round the four of us. Steve [Nieve] lives in France, so we had a couple days waiting for him to chime in. [Producer] Sebastian Krys had agreed to pull all this into one place. About three weeks later we had the record.

It came together very quickly. At one point, the Roots album aside, there was a very long gap between albums, and now it’s been a pretty prolific stretch.

COSTELLO: The Roots, they had to lure me in -- as they say -- out of the hills with a hunk of raw meat. I had made this maybe slightly melodramatic statement I was going to concentrate on presenting... I had this vision I could be a rock 'n' roll George M. Cohan. He's Irish blood. I thought, "I'll be a showman." By the time I got to 2010 or 2011, I had so many songs. My dad had just passed in 2011, and maybe I had him in my mind. I thought, "I’ll do what he did." Sometimes that’s the reaction to the passing of a parent. I wasn’t trying to honor him, it was nothing sentimental, but I thought -- he just went out and played whatever he played in his show every night. I’ll do that, I’ll create a framework, so I revived the spinning wheel concept. That was a lot of fun. Then you’re throwing all of your songs into the wheel of chance.

Then I created Detour, with the television set. I’d been working on this book. When that came out, that tour seemed to link with storytelling. I have to say, before Bruce Springsteen did Springsteen On Broadway, that wasn’t scripted like Bruce’s piece -- which was beautiful, I didn’t see Bruce’s show until the last night of the second run. I was afraid if I went along I’d think, "Why did I carry that TV set around the world when I could’ve just stood on the stage and tell stories and sing songs?" [Laughs] I had a lot of complicated architecture I personally had fun with. I could talk about my family without it becoming too sentimental. Tell some truth, some lies.

I did versions of stories I'd written out longform in my book. I’d boil them down and use them as my introduction. Those things would sometimes be repeated. Occasionally I’d find myself saying, you know, "I speak about my father every night in this very kind of romantic way, but in fact he wasn’t a very good father and neither was I." Then I’d sing "Toledo," which is a song about coming back to your hotel room and finding the red light going and you know you’ve been found out. You’ve been somewhere you shouldn’t have been. That was my dad’s life as well as mine at some point.

That’s when I realized not everything had to happen in song because it happened to you last week. It could be something anytime in your experience. The better you get at writing, the less selfish you get about it being your diary or your last will and confession. Maybe it allows the listener's imagination in a bit. Because of some of the collaborative things I’ve done I’ve had to cede some of the invention to those people, whether it'd be Paul McCartney or Burt Bacharach -- where I was co-writer and co-lyricist, so I had to understand the implication of music coming to me. I had to recognize the distance of songs written on the piano and all the harmonic possibility and the mood and the dramatic possibility piano brings, relative to the way guitar tends to pull the words out of you in a rush.

The initial thing with these songs [for The Boy Named If] was, when they were lying in bits on the table, I recognized them all to be different times in life all emerging from the title. The imaginary friend, which is a charming alibi for a seven-year-old breaking a cup, and a less endearing... "Yes, I had to stay out all night dear, because my other self told me to." That’s what the songs turned out to be. What it's about is what you hear. You can listen to the songs and they explain themselves.

R. Whites Lemonade Commercial With His Dad (1974)

As far as I can tell, your first recording was this lemonade commercial with your father in 1974. What do you remember from that?

COSTELLO: My father had a really unusual career, in the sense he began as a jazz musician and when I was born... I don’t know, out of expedience or responsibility, he was hired to be a vocalist for a very successful dance band. He had a very successful career until about 1969, when I think he got a bit disenchanted with singing whatever song was put in front of him that week. In those days, dance bands just had to interpret the hit parade. He wanted to make his own choices. He grew his hair really long and kinda looked like a hippie. In this period, he had friends who were younger musicians. The places a man of his age -- now in his forties -- could play were working man’s clubs and social clubs in the north of England. He still had a name from having been on the radio. He had covered an awful lot of musical ground both from that band and under aliases.

He would record at nine in the morning, these cover records. One of the founders of pirate radio -- Allan Crawford, who’s less celebrated in the history of pirate radio, the partner of Ronan O'Rahilly. He took it a stage further than his partner. He ran a ship moored in the Thames Estuary, and he actually believed not only could he subvert the BBC with a pirate radio station, but that he could subvert the record companies by recording soundalikes and playing them on that station exclusively and they wouldn’t have to pay royalties, only to publishing. He was from publishing. My father would go in and record four titles for these little EPs.

This is 1964. He’s recording "I Wanna Be Your Man" by the Rolling Stones under the name the Ravers. He's singing "If I Loved You" from Carousel. He’s singing "Blowin' In The Wind," as a member of the Foresters, who were supposed to be Peter, Paul, And Mary. Nobody knew he was the singer on any of these songs, because he changed his voice and he had a different name. Do you get a clue of how I ended up being Elvis Costello? [Laughs] It's like a hidden history of English pop music. We heard everything filtered one way or another.

When I was a teenager, I picked up the guitar. I started writing songs almost immediately. When I was 15, we moved to Liverpool and I went to school for the last two years there. I started playing in folk clubs, I had just started playing in public. We got to Liverpool, there was a divide between the traditional music and writing your own songs. I formed a duo there with a boy I met. We played together for two years and believed we were going to conquer the world the way you do when you’re 17. By the winter of '72, I decided I was going to go back to London and live with my dad and try to make a career in music. When I got there, my dad picked me up at the station and told me, "You’ve got a brother." I said, "When did that happen?" He said, "Four weeks ago." So I stayed until I could get somewhere else to live, because I felt really awkward living with my dad and his young wife and my brother, who I love.

I fell in with a group of musicians and I played with them a while and that didn’t work out. My dad all the time was making money doing this secret work. He used to do commercials. One day he said, "I've been asked to do this lemonade commercial, they want me to do an Elvis Presley voice." They'd written this silly jingle. "They wanted the background vocals to sound like a Merseybeat group, would you come to the studio? I'll do the lead Elvis vocal, but the professional backup singers can’t sound like the Swinging Blue Jeans." I can do that all day long.

I'm in the studio, and then the ad men come in. "We're going to do two versions of this commercial, one is this guy's having a fantasy about being a pop singer, he goes down to the kitchen, gets a bottle of pop out of the fridge, and bursts into it. That’s the pitch, 30 seconds. We also want to make a version where he actually sees himself onstage." The piano player looked too old to be in it. My dad who had long hair -- he’s exactly the same age -- they put him on piano. Bass player was also an older guy. So I got stuck on bass. If you see that commercial, I'm in a red T-shirt. Not very flattering. I was maybe 18. That was my first recording session.

Writing With Paul McCartney (Late '80s)

You were writing with McCartney in the late ‘80s, with songs appearing on each of your records in the late '80s and into the '90s.

COSTELLO: It's the connection between me and Kanye. The next top 20 record is Kanye and Paul. Paul had a lot of hit albums. But his next top 20 single after "My Brave Face" is Kanye and Rihanna. If only he’d thought to put all three of us in the band, imagine! We would’ve gone to #1! Kanye, Rihanna, Paul, and me. Come on, there's still time.

I don't know when you’d first met him, but obviously this sounds intimidating, to say the least.

COSTELLO: Again, it goes back further than you would imagine. I don’t want to tell you the whole story of my life, but. The first time I met Paul was for the Concert For Kampuchea in 1979. It was Wings' last gig. There was a massive cast. Rockpile opened up with Robert Plant singing for them, we played, Wings, and it ended with this giant thing called the Rockestra, with like three drummers. I wasn't in the band. But I did get to meet Paul briefly. I didn't know Wings were breaking up. That wasn't announced at that point. Paul didn't tour for a while after that.

Obviously, I'm exactly the right age to have been hit full force by the Beatles. The big event of 1963 -- three months before they came to the US, they had played the Royal Variety Show. Annual benefit show, sponsored by the Royal family. My dad had played it in 1963 with the band he sang with. Also on the bill, the new sensation of that year, the BTS of 1963, the Beatles. And lots of other jugglers and conjurers and belly-dancers, just like all variety shows. Marlene Dietrich, and her accompanist Burt Bacharach. If you were to be spooky about these things: Two people on that bill in 1963, I ended up writing 15 or more songs with.

I get this invitation eight years later, after [Concert For Kampuchea], would I come and write with Paul. During the '80s, we had done two records at their studios, the first of them being Imperial Bedroom. That was a record where we were almost shamelessly saying, "Let’s give ourselves the space." We read in a book, "Didn’t the Beatles go to Abbey Road for weeks and weeks when they made Sgt. Pepper?" Wasn’t that three months? Maybe if we just do 12 weeks. That's enough to make five records in our book. Bear in mind, This Year’s Model was made in 11 days. My Aim Is True was made in 24 hours of studio time total. None of our records took more than three weeks. To do 12 weeks, and to have Geoff Emerick, the man who had engineered Sgt. Pepper... But what I didn't know, when we agreed to do it in there, was that Paul McCartney would be in the other studio the other end of the hallway, working with George Martin on what I think was Tug Of War.

We'd see Paul in the hallway, this is only two years after [that show]. One day, a little kid ran into our control room, about seven. A little blonde kid, then a blonde girl ran after him, then a dark-haired girl ran in after her, then their mum and it was Linda. It was like, "Hi, I'm meeting the family!" It's like come to work with your dad day and they ended up in our studio. That was a break in the ice. We were trying not to bother them. We didn't want to be starstruck. I'd see Paul and we’d talk. We'd be playing Asteroids in the lounge.

I got this invitation [years later], which I thought was a prank at first. I was invited down to his studio on the south coast. I took a pretty good sketch of “Veronica.” I was afraid if I got there and nothing happened, it would just be terrifying. I took a bit of a sketch that didn’t have a proper chorus or bridge worked out. He took to writing that. I told him it was a happy tune with a serious story, and he seemed to like that. We immediately struck it off. The next thing we did was something he prepared. So we both had the same idea: Let's not stare at a blank page. After we wrote those two songs, they flowed very quickly. We had three or four writing sessions. We had a big stack of songs, and we started recording.

We were co-producing the tracks, which at first was tremendous fun. It was really raw. I was sometimes singing lead, leading the band so Paul could play bass. Sometimes I'd play piano, which I can't really do. I was just hammering stuff out. It was very free. At some point, he started to want it to be bit more developed, and I wasn’t equipped for that. The record was a long time coming. When it came out, I had made Spike with T Bone Burnett. It was very widescreen, like Lawrence Of Arabia with less camels. It was very expansive. Four cities. It was a sort of, "Let's have everything." Let's have an Irish ensemble, let's have a New Orleans -- everything I’d dreamed. Meanwhile, Paul was making this record [Flowers In The Dirt] bigger and then smaller again. When it came out, it wasn’t really so far away from what we’d started to do. I thought it was going to come back very very shiny, but it didn't. "That Day Is Done" was really soulful, I thought, the way he sang it. I got one kind of co-vocal on it.

It was a very funny feeling, because the way the lines worked out I got all the sarcastic lines and he got all the dreamy lovelorn lines. He stopped during the demo and the look on his face was just kind of, "I think I've seen this movie before." I would never dream for a minute I was being John Lennon, that's ridiculous. They were teenage fans that went to outer space. There's no way anybody could be John Lennon. But because of where my voice lies, I would end up singing the low end of the harmony, which was how Lennon sang most of the time. As you can hear, there's some Liverpool accent in my voice from my parents. Not very pronounced, but of course the more I spoke to him the more it came out, as often is the way. It got worse and worse until he just went, "Hold on, stop the playback." [Laughs]

Little did we know the horrors that lay ahead in the '90s, but there were already quite a bit of people copying the Beatles in 1988. Paul McCartney could occasionally refer to a cadence that put you in mind of his other work. If you think about Wings, it was a very dramatic shift. I don’t know what your sense of harmony is, but it wasn’t just mood and production style. It was a completely different language of music. Which is an amazing thing to achieve. But by the time '88 came around, he was maybe ready to make a couple passive references without being a pastiche. I really enjoyed it.

When Linda passed, it was very devastating of course. Chrissie Hynde and another friend of Linda’s put together a tribute concert at the Albert Hall. A bunch of us played. I was at the side of the stage, and John, Paul's assistant, said, "This is actually really difficult for him." As it would be. It doesn't matter how famous you are. You don't get anything to protect you from that kind of sadness. I went and sang harmony, and he liked that, and it gave him another person onstage. He turned to me at the end of it -- this is at the rehearsal -- and he said, "Do you want to stay up for the next one?" I said, "What is the next one?" He said, "'All My Loving,' do you know it?" Uh, yeah, I know it. [Laughs]

He just kicked it off. To do that, and get to the second verse and take the low harmony -- I could've done it in a coma. It was so second nature to me to go exactly where that was supposed to phrase. In the evening, it wasn't anything like that, it was everybody up onstage all bellowing into different mics, all out of tune. That magic moment went away. One of the only two times we’ve been onstage. I did "One After 909" with him one night when he was given an award, it was just the two of us hammering it out like a skiffle group. I know what that thrill is, that's seen in Get Back. Not that you’re being someone else. But it’s thrilling to sing with him. It’s tremendous.

Making Wise Up Ghost With The Roots (2013), Dopamine Supergroup (Present)

One of the other collaborations I wanted to talk about: You did this album with the Roots we mentioned earlier, back in 2013. In 2020, Black Thought was saying there was a supergroup called Dopamine with him, you, Nathaniel Rateliff, T Bone Burnett, DJ Premier, Cassandra Wilson. Are you still pursuing that?

COSTELLO: It made a guest appearance the other night on my pirate radio show that I did from the basement from an independent record store in Liverpool, on Smithtown Road where my mother's from. In a store called Defend Vinyl. I found out the shop is about half a mile from my mom’s old neighborhood, this one continuous road that stretches up from her place near the city all the way to Penny Lane, funnily enough. I asked Graham, the owner, if I could come do something in the shop to celebrate the release of The Boy Named If after he told me there was some recording equipment in the basement. So I set up there with a turntable and a laptop and a microphone and I went on YouTube. I think everyone anticipated a half an hour promo appearance. I did three and a half hours.

I said to T Bone a couple days before, "That Dopamine record, can I play any of them on the air?" It's not going to be something where it’s going to be on a website. It's just going to be in the air for the duration of the record. He said, "Let me think about that for a minute." The next day he sent me a mix, it’s not even necessarily the mix -- there are lots of mixes of this piece, by its nature.

You asked me a question before about stopping recording at one point. I can't exactly remember how this came about except it must've been in the immediate aftermath of the release of National Ransom. I’d worked with a group of largely acoustic musicians for two years, and we played everywhere in the world. It was a different feel. It didn't have a drummer. I had some songs from that record that were never played, as a consequence. I didn’t have any assembled band and I went in to do the Fallon show and we learned a couple of tunes. We learned this song "Stations Of The Cross," which was a very intense song, partly based on the experiences of a friend of mine in New Orleans. I played Wurlitzer, which is unusual for me.

Of course, you have so many great musicians in the Roots. They laid a track down and we did a rehearsal. When I did rehearsal with the Roots in their little TARDIS-like cupboard where they used to record in the hallway, I saw Quest and he said, "I’m so tired, I was in the studio all night with D'Angelo, and now I have to learn this Inner Mounting Flame and Birds Of Fire music. I said, "What the hell for?" He said, "John McLaughlin is sitting in with us tonight so we're going to play that in and out of the commercial breaks." So I said, "Could he play on my tune as well?" So I’m in the cupboard, rehearsing "Stations Of The Cross," with John sitting two feet away from me. I'd never met him. He'd never heard the tune. I said, "Look, it's an E minor or D minor vamp, just go." Of course you get 12 hundred thousand notes, John's just flying all over.

At the end of the rehearsal, Quest and I have literally said about nine words to each other in all of this process. He said, "You know you’re coming into the studio with us." So we plotted this thing out over the next couple of years. The one thing it didn't involve was the whole band, the whole collective of the Roots being there with us. People that love the Roots obviously remarked on Tariq's absence from that record, as you’d expect as it was credited to the Roots. But Roots members came in in parts to build the arrangements. The record was like a collage of sound, really. I’ve been to the [Fallon] show many times since then, to visit as a friend. I’ve been on the show maybe once or twice since then.

Suddenly, T Bone announced he was doing this piece called "Dopamine" that had this repeated chorus about statues and skeletons. I sort of thought I knew what that meant. He said, "It’s DJ Premier and Tariq and I want you do something on it, and then Cassandra Wilson is going to sing on it." Then every time I spoke to him it was like, and now Nathaniel Rateliff is going to sing on it, and Rhiannon Giddens is playing banjo on it. We’ve got a whole section with more singers. I feel like it’s a magazine you’re reading through, where the ideas and personalities are overlapping and people are picking up cues. It's not like we're all singing one song. Tariq did amazing verses, and I hadn’t heard them until after I'd recorded my part. It was extraordinary how they were working on parallel themes but I don't think he’d heard my verses when he did his part. When the mix was put together, it seemed as if we were meant to be in this universe.

Obviously, his delivery is so remarkable. To my ear, he’s the greatest at what he does, in every respect. The ideas, the delivery, the rhythmic command, everything that’s informing it -- the bravado, but also the vulnerability in it. It seems to me, at times, it’s from a deeper lineage way back to spoken records and things that happened in the late '60s. These are all things I've heard, and have had an emotional impact on me without necessarily thinking I can do that. So I started out to sing these words, and it didn’t feel right because of the rhythm. So I just spoke them. I sounded strangely Welsh on some of the songs. Then all this spooky stuff started happening from Cassandra and Rhiannon.

I feel like I'm giving only a hint. I have no idea where all this ends. I don't want it to end. I like the idea it's an open-ended dialogue. One voice is not superior to another. There's a refrain, but it's not like we’re all linking arms and singing. It’s not "We Are The World" just because there’s a lot of people on it. I think the act of people being in one mind, to be inside something and let it develop, is something I haven’t encountered before. I was very grateful for T Bone to allow me to surprise people with it, and it sounded just beautiful on the radio. I went out of that piece into something utterly different, and so it carried on until the end of the night.

Producing The Pogues' Rum Sodomy & The Lash And Working On The Early Versions Of "Fairytale Of New York" (1985/1986)

I knew you had produced the Pogues, but I was surprised to find you were involved in the early gestation of "Fairytale Of New York."

COSTELLO: I produced their second record, and I took the same approach I took to the Specials in 1980. I quit production as a full-time occupation after that [Pogues] record. The first record I produced was the Specials, which was a band I loved and I thought a professional producer could ruin them in the studio by taking away the fire and that raw thing they had live. I knew Jerry Dammers was some kind of genius musician, had a very clear vision of what was supposed to happen. There was such a disparate group of personalities in it, it needed someone to sit in the middle of it other than Jerry. I did that record.

Then I went with my friends Squeeze and produced a record where you had a tremendous amount of musical accomplishment. It was just a pleasure to sit there. I had Roger Béchirian, who had engineered my records, to be there and make it sound great -- so I could just sit there and make a few suggestions. I would say, "That's the take." "Paul Carrack should sing 'Tempted,' not you." That didn't go down very well at first because of course Glenn imagined him singing that song. But guess what, we had a hit with it, so I guess I was right in that respect. I heard Paul putting it over to a broader audience.

When the Pogues came along, they were a thrilling sound. You could hear right away that MacGowan was a top songwriter, had these incredible songs. A whole idea that was different. They were great live, they opened up for us -- they were chaotic sometimes. Getting them in the studio, my job was, again, not to take the edges off but to have it be musically coherent. Which wasn't always possible. I know Shane didn't like me at all. He never liked me. He was suspicious of me because I wasn't a punk, as far as he was concerned. He held to that. I think he thought I was a dilettante. I think the music I’d made immediately before that wasn't my strongest game, so there was every reason. The fact I’d moved around a lot [stylistically], even in that time. I held in there.

Sometimes I had to pick up an instrument and play it, because it wasn’t all going to work otherwise. But there were some very good musicians in that group as well. There was feel. The main thing was there was tremendous feel and force. I carried on producing for a bit, we did a couple other things. We went to Spain and we were in this awful movie [Straight To Hell], this pastiche of a parody of a Spaghetti Western which is a pastiche of a parody of something else. It was fun to be in the desert with Joe Strummer and a group of actors and Courtney Love. That was a long time ago. We did some music for that. I did a piece with my father playing trumpet, actually, and I produced some of the soundtrack pieces. [The Pogues and I] made one more EP, which was cool, and then we did "Do You Believe In Magic?" which you can't really imagine the Pogues doing.

Then Shane had said this thing about the Christmas song. I must admit, I couldn’t imagine him writing something... it wouldn't be a sentimental song. I wouldn't have imagined, anyway. It's gone in to legend that I bet him. I don't know that that happened. That might've been romanticized. I don’t think we were on that friendly terms at that point that we would've made a joke bet. He barely tolerated me being in there, because I told him he needed an oboe on his record not a trumpet. Shane would describe things in references to other things or movies. You had to listen carefully. One of the things the band was obsessed with: They would do recitations from the script of Once Upon A Time In America. The Ennio Morricone music was obviously a part of that, and I think that set the mood for the opening of "Fairytale Of New York." This elegiac sound. Which is why I said oboe. I thought it should be more orchestral.

The original arrangement was the bass player, my ex-partner Cait O'Riordan, I thought singing it very well. She did very few vocals in the band, but she always sang well. She had a good voice. But somewhere along the way they decided it would be slightly more three-dimensional with Kirsty MacColl. I'd left the scene by then, so I can’t speak for the final record. Steve Lillywhite produced it. Steve, I like and I know him, I would say it to his face -- he kind of poshed them up. It didn't move me. There were some terrific songs on it, but I would've produced it better. There you go, I said it.

When it was all said and done, those are the truly great songs MacGowan wrote. "The Sick Bed of Cúchulainn," "Sally MacLennane," "A Pair Of Brown Eyes." "A Pair Of Brown Eyes" could [have endured the same way] -- and "Rainy Night In Soho" as well, which I did produce. I almost got Rod Stewart to record "The Old Main Drag," which would've been fabulous. That one brief time I was going to produce Rod in the '90s. I tried to persuade him and he wouldn't do that one I said "OK, 'Rainy Night In Soho.'" We didn't quite get there. He stole my two other best ideas and went off and made the record with somebody else. [Laughs] That cheapskate! He couldn’t afford me. It was fun trying to propose Shane MacGowan songs to him. I figured, he's sang Tom Waits songs he must be able to get inside this. "Old Main Drag" might've been a bit rich for his blood, you know?