- Stranger/Interscope/Polydor

- 2012

"There's backlash about everything I do. It's nothing new." That's Lana Del Rey talking about her instantly infamous Saturday Night Live performance only a couple weeks after it happened. That she was already so jaded following a scant few months in the public eye speaks to the amount of vitriol that Del Rey garnered leading up to her major-label debut album, Born To Die, released 10 years ago today. There's no moment during that SNL performance where it looks like Del Rey thinks that her career might be on the verge of being over. Since the very beginning, she has always played defense. Even a decade later, she is still addressing that one performance. "It wasn't terrible," she told Elton John in 2019, and in a tragic twist straight out of a Lana Del Rey song: "It was the one night in all my time performing that I wasn't nervous."

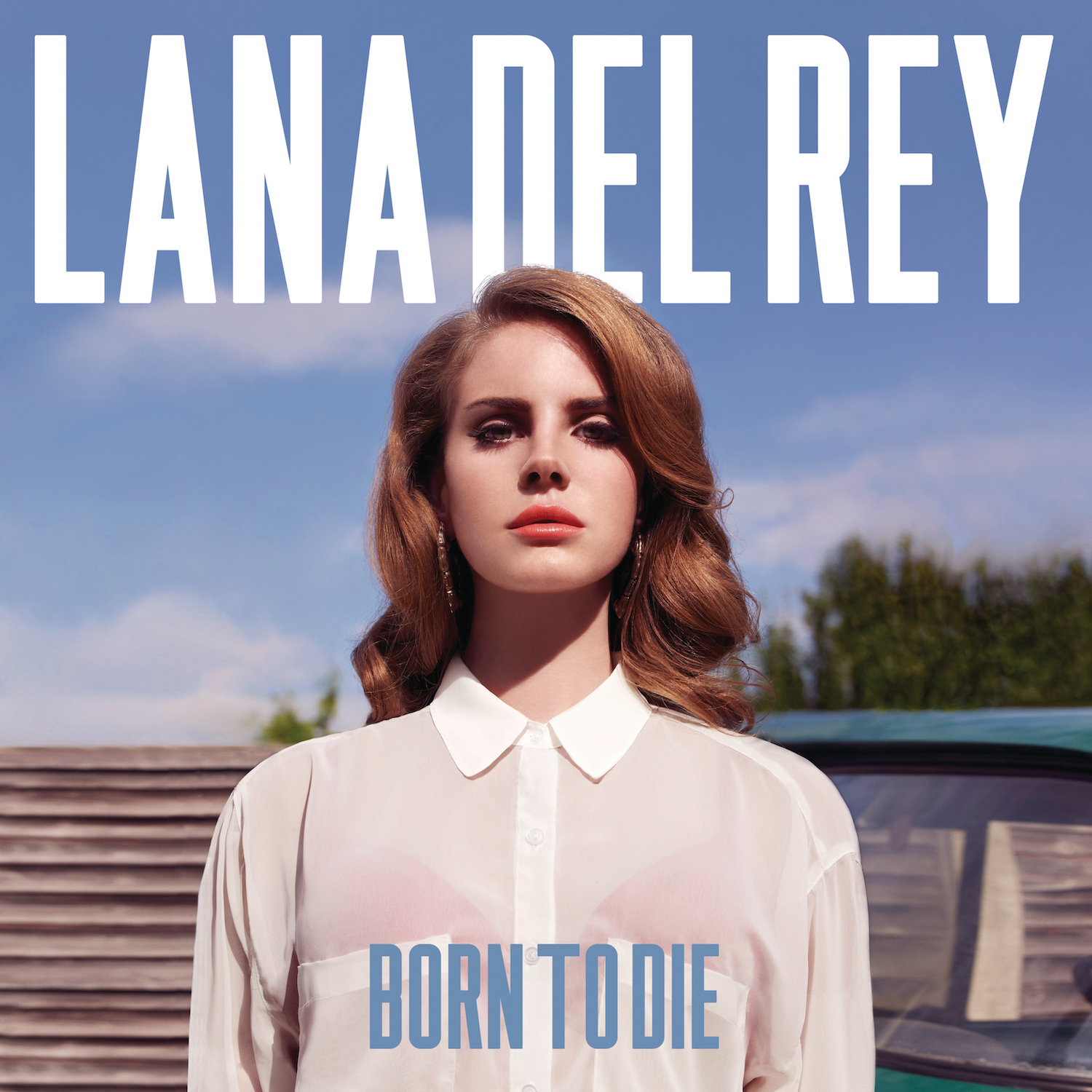

Said performance, though pitchy and all over the place, really isn't that bad -- especially on a show notorious for having awful sound for its musical guests. But judging by the immediate reactions on social media and in the comment sections of blogs like this one, you would think Del Rey committed a war crime. At that point, Lana Del Rey frenzy and fury was at a fever pitch. After the release of her first proper single "Video Games" in the summer of 2011, she became a lightning rod for debates about authenticity and good taste. Del Rey didn't cower away from the criticism; she leaned into it, fought back against it. On the cover of Born To Die, Del Rey stands stock-still and stares at the camera, as if lined up for a firing squad. She was ready.

Lana Del Rey arrived to most of the public as a persona fully formed, but Born To Die was not her first album or her first attempt. It's hard to determine how much of Del Rey's self-mythologizing to take at face value but the generally agreed upon narrative goes like this: Elizabeth Woolridge Grant, with a name straight out of an Edith Wharton novel, was born in New York City. She was raised upstate in Lake Placid. When she was a teenager her parents sent her to a private prep school in Connecticut after she exhibited some rowdy behavior. After she graduated from there but before she attended Fordham University, Grant lived on Long Island with her uncle and worked as a waitress. It was then that she learned to play the guitar and started writing songs and performing in clubs around the city. After attracting the attention of a small label and receiving an advance for her first album, she said that she moved to a trailer park in North Jersey. By 2010, Grant was going by the slightly alternate spelling of Lana Del Ray. Her debut from that year would be scrubbed from the internet a few months after it was released (and eventually leaked back out once Del Rey took off). With new managers, she relocated to the UK and started plotting a re-introduction, which would involve some surreptitious YouTube uploads, an eventual major-label deal, and a whole lot of buzz, both manufactured and organic.

Even before Lizzy Grant became Lana Del Rey, she displayed a fascination with aesthetics. "I'm very swayed by how things look on the outside," she said in a 2009 interview. "Though I have been burned by what's on the inside of them so many times -- don't get me wrong. But I still have love for something that hits my eye right. A flag waving or a Pontiac Grand Am -- I didn't even have to know what those things stood for to know they were beautiful." Lana Del Rey was an artifice, a name Frankensteined from signifiers of grandeur that also communicated a false exoticism. Del Rey's persona was drawn from old money glamor and Hollywood's golden age; she channeled patriotism for a dying empire. At one of her first live shows after becoming a topic of conversation, she was billed as the Queen Of Coney Island.

That her entire identity was met with skepticism is not exactly surprising. Del Rey has never been a particularly adept communicator to the public; her interviews and dispatches often come across as a combination of overly earnest and woefully out of touch. The breakdown between where the persona ends and the "real person" begins is muddy, especially now after a decade of actual fame has warped some of the project's seemingly more tongue-in-cheek intentions. That has caused consternation and outrage in more recent memory, and at the time it raised much intrigue and ire. In the months leading up to the release of Born To Die, the discourse surrounding Lana Del Rey was overwhelming to those living at a certain level of online. By the time the album actually came out, Del Rey was primed for a fall from (dis)grace.

Born To Die was eviscerated by critics when it came out. Two weeks after the SNL performance, the knives were out for Del Rey. "For all of its coos about love and devotion, it's the album equivalent of a faked orgasm -- a collection of torch songs with no fire," Lindsay Zoladz concluded in the Pitchfork review -- the album landed with a thudding 5.5. "Given her chic image, it’s a surprise how dull, dreary and pop-starved Born To Die is," Rob Sheffield wrote in Rolling Stone. "The whole thing is just a godawful mess," Tom Breihan wrote in our own Premature Evaluation.

The contemporaneous reviews aren't entirely wrong. Born To Die is not a perfect album. It's bloated and overproduced. Del Rey's reflections of transactional relationships and aspirational wealth are let down by some truly clunky lyrics. The string arrangements often sound cheap; her blend of slinking trip-hop and lounge lizard sleaze isn't seamless. "Video Games," with its slow tempo and burnt-out detachment, is restrained compared to the rest of the album. Born To Die is a pop album first and foremost, with a desire to capture listeners in a way that her other albums lack. It's the Lana Del Rey album I return to most often nowadays because of how fun and funny it can be. Most of Del Rey's follow-ups to Born To Die are self-serious and morose, sanding down some of the personality and sense of humor that's so evident on her major label debut. A decade removed, Born To Die really goes for it in a way that Del Rey doesn't often do throughout the rest of her discography.

For all their pomp and fizziness, these are clever and deceptively layered songs. Take the opulent "National Anthem," where Del Rey offers up deference while making sure that the object of her devotion lives in the right zip code. "Money is the anthem of success/ So before we go out, what's your address?" She sings straight-faced about the intoxicating allure of wealth and sex, then cuts herself down with quips and knowing nods. She balances camp with sincerity in a way that manages to sweep you up in the majesty of the American dream of power and fame while also exposing how hollow it really is. "Off To The Races" jet sets from the Château Marmont to Rikers Island, and Del Rey begs for all her sin and seduction to be forgiven in the end: "My old man is a thief and I'm gonna stay and pray with him 'til the end/ But I trust in the decision of the Lord to watch over us/ Take him when He May, if He may." Born To Die is filled with songs that feel like they can only live in this early era of Lana Del Rey: "Diet Mtn Dew"; "Lolita"; the effervescent "Radio," where she somehow winningly forces "cinnamon" and "vitamin" to rhyme.

There are also hints of the more narrative directions that Del Rey would go on her next albums. "Blue Jeans" tells a whole story in its weaving of an everlasting love between a small-time gangster and the foolish one who waits at home for him to return. "Carmen" paints a portrait of a woman who, in Del Rey's lyrics, street walks at night and is a star by day. "This Is What Makes Us Girls" flashes back to those troubled high school years, when she was still drinking "Pabst Blue Ribbon on ice." It takes an effective serious turn at the end when Del Rey laments all the people she's lost: "They were the only friends I ever had/ We got into trouble and when stuff got bad/ I got sent away, I was wavin' on the train platform/ Cryin' 'cause I know I'm never comin' back."

The knee-jerk criticisms of Born To Die are almost understandable, especially if it turned out that Del Rey ended up being some flash in the pan. But she continued to pervade popular culture after Born To Die came out. Later on in 2012, the album was reissued with the 8-song Paradise EP attached; "Summertime Sadness" had a surprising commercial long-tail with a remix the following year that remains Del Rey's highest-charting single. The tides turned back in her favor by the time she released her follow-up Ultraviolence in 2014. If anything, the critical establishment overcorrected in reviews for her next few albums as if to compensate for Born To Die's initial reception -- at least until 2019's Norman Fucking Rockwell!, Del Rey's best attempt so far at some kind of definitive statement. The locus of attention that Del Rey draws, both positive and negative, has also not faltered over the last decade. She still has a bad habit of putting her foot in her mouth, just about as often as she puts out a song that feels truly life-changing. Since Born To Die was released, Del Rey has been in a constant churn of controversy and adoration. But Del Rey has been an attention-grabber from the start and, for better and worse, she has done so on her own terms.

"I know for myself it took years of walking into the same [kind of] labels I'm signed to now to have a chance to be understood as a person telling a story rather than a trend," Del Rey reflected in an interview last year. "I fought very hard for that and I'm so glad I did. People may get caught up now and then in the fact that I have a strong look or presentation, but at the end of the day what’s important to me is the fact that I've been able to tell my life's stories, dreams and encounters for over a decade, and that in itself is a triumph." There's a backlash about everything she does. It's nothing new.