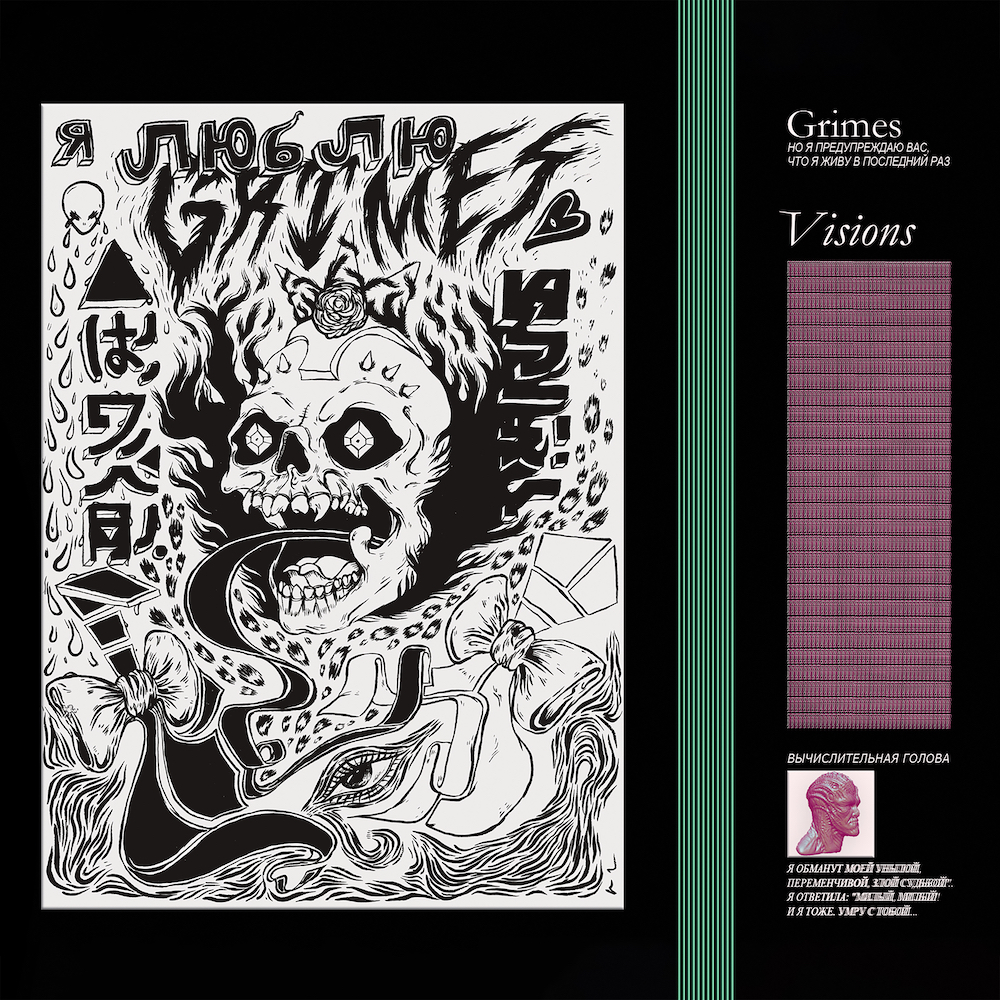

- 4AD/Arbutus

- 2012

It's a tale as old as time: Artist goes on a weeks-long amphetamine binge, blacks out all their windows, isolates themselves from their friends, doesn't come up for air, and ends up making a weirdo art-pop album that catapults them from internet curiosity to contentious public figure. The origin story of Grimes' landmark album Visions, which turns 10 years old this Monday, is mythic in its way. The narrative that Claire Boucher spun about Visions painted its creation as a sonic vision quest, a way to plumb the depths of her soul and her creativity. "Once you hit day nine, you start accessing some really crazy shit," Boucher explained. "You have no stimulation, so your subconscious starts filling in the blanks. I started to feel like I was channeling spirits. I was convinced my music was a gift from God. It was like I knew exactly what to do next, as if my songs were already written."

In some listening notes that were recently written by Boucher and included on a 10th anniversary reissue of the album, she admitted that Visions was less a spiritual possession and more the result of "learning how to make music and just utterly loving every minute of it." There's a purity in Visions' desperation to land on something concrete: "I miss the insane version of myself that made this and was totally confused about how humans perceive music," she wrote. She described her mentality at the time as "super disconnected from everyone and laser-focused on being an artist."

Grimes is more rooted in a physical community than one might think given how her actions nowadays seem to take place exclusively in the metaverse. She came up in a very specific scene: the drug-addled art world of Montreal. Though originally from Vancouver, Boucher moved to Montreal to study at the prestigious McGill University, pursuing a dual degree in neuroscience and Russian language. But it wasn't long before Boucher, still in the throes of her rebellious teenage years, found herself taken in by that idea of being an artist. (Before she was ever known for her music, the first time Boucher's name appeared in the press was when she was held by the US government after a rickety houseboat she constructed with her then-boyfriend was impounded after a failed attempt to sail down the Mississippi River.)

She had no formal musical training when she started recording and releasing music as Grimes on her MySpace page, quickly cultivating an avid online group of followers. (The name Grimes comes from the genre dropdown list that existed on the defunct social media site -- multiple "grime"s, if you will.) Her first two albums came out a few months removed from each other in 2010: the Dune-inspired Geidi Primes and Halfaxa, which took its cues from medieval Christianity. Boucher dubbed her sound "post-internet" in an interview, a designation that she would later grow to resent. There was something metaphysical about Grimes' music in those early stages, though. As she honed her skills, performing live and teaching herself the ins-and-outs of production, things started to come together. On 2011's Darkbloom, a split EP with fellow Canadian musician d'Eon, Grimes hit on her first underground sensation with the hypnotic "Vanessa."

That song acts as something of a blueprint for Visions' two most enduring tracks, "Genesis" and "Oblivion." They work almost as polar opposites of each other despite utilizing a lot of the same tools (a looping synth, Grimes' breathy intonations). But where "Genesis" is a gossamer reflection of weightless love that feels like gliding through water, "Oblivion" taps into something far more sinister. The latter was written as a way to process a sexual assault, and Grimes plays out a revenge fantasy with claustrophobic elation. "I never walk about after dark/ It's my point of view/ 'Cause someone could break your neck/ Coming up behind you, always coming and you'd never have a clue," she sings in its opening lines. Its chorus, taking a page out of the theatrical menace of the Knife, is a sly inevitability: "See you on a dark night." Coupled with its iconic music video -- in which Grimes surrounds herself with the stench of masculinity in a men's locker room, at a motocross rally, and at a frat party gone wild -- "Oblivion" was both a political statement and a perfect pop song.

"Genesis" and "Oblivion" are part of the reason why Visions took off the way that it did. The rest of the album is less immediate, more concentrated on introverted electronics that feel more apt to come down to in your room than to blast at a party. As a moodpiece, Visions is still plenty compelling. It's filled with longing ("If you want me to, I will wait for you," Grimes chirps on the introductory track) and it's darkly romantic, even and maybe especially at its most sinister. On "Eight," Grimes rides a shadowy groove and plays up a twinge of confidence: "Go where you want to go/ When you get there, you'll still be wishing you were by the phone." The sprawling "Skin" is gorgeous to sink into but also feels lost and unbelievably sad, someone mourning their loss of definition: "Soft skin you touch me within/ So I know I can be human once again." The gently cascading "Symphonia IX (My Wait Is U)" is about Grimes' relationship with her muse as she strives for perfection: "The need to be the best before the need to rest/ Oh, I would say yes."

But Visions also sounds like the sort of music that someone would, say, compose during a two-week drug binge -- there are a lot of good ideas, but also a lot of repetition, and songs that go on for too long or don't really go anywhere. Her voice, always alluring, helps tie together even her most disparate sounds, but a little too much of Visions is just vapor. Maybe it's just because I know now what Grimes can sound like when she sharpens her songwriting skills, like she does on her true masterpiece Art Angels, or when she takes a more considered approach on Miss Anthropocene, which is more of a mixed bag. But on Visions, although it's clear that Grimes has a way with topline melodies, her production is still rudimentary. With some distance, Visions sounds more like sketches for ideas she'd develop more later on -- there's a through-line between a song like "Nightmusic" and "Kill V Maim," or from "Be The Body" to the thumping "4ÆM."

Grimes has always wanted to be the best at what she does. "There's a psychology to success," she said in an interview around the time that Visions came out. "I was reading all these biographies and watching documentaries about people who are successful. It seemed like the only thread amongst everybody is that unflinching, 'Yes, I can do this and I am the best.' It’s a personal rhetoric that you can develop. Like, if you go and tell journalists, 'I’m the future of music,' then people start printing that. So I’m just going to tell everyone I’m making the future of music. I’m going to force the situation to happen."

That manifestation, and the confidence that comes along with it, has mostly made her wish come true. The most magical moments in her music feel like a battle between introversion and ambition. "I really hate being in front of people. But I'm also obsessed with becoming a pop star," she also said back in 2012. As with another artist who released their breakthrough album just a month before Visions, there has always been a disconnect between what Grimes says and how her music comes across. That's part of what has made Grimes such a fascinating and polarizing figure -- she was genuinely weird and open in a way that was refreshing at a time when musicians were often so guarded and inaccessible. As an early adopter of social media, she spoke directly with her fans, usually without any sort of filter. That lack of filter has gotten her into trouble more than a few times. And over the past decade, as Grimes has become more of a tabloid staple, her worst tendencies have been exacerbated.

But it's interesting to revisit some of Grimes' early interviews now in an age when she has become so vocally technocratic. Boucher always displayed a fascination with the future, but there was also a time she expressed a healthy skepticism of it. "It's really important to be disconnected from the digital world. Or else you give in to fully being a cyborg, which simultaneously intrigues and terrifies me," she once said. Also: "The Internet's just like guns or drugs. It's extremely powerful, and therefore it's extremely dangerous." The power and danger that come with the endless chatter of the online world now courses through Grimes' music -- but Visions felt like an escape from that madness, not an embrace of it. The compressed circumstances under which the album was made are not exactly healthy, but that detachment from the outside world is beneficial to making enduring art. If anything, Visions' legacy underlines the importance of logging off.