September 9, 1995

- STAYED AT #1:3 Weeks

In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

The term "gangster rap" dates back to 1989, when Robert Hillburn used it in an LA Weekly cover story on N.W.A. At that point, it was just a descriptor. N.W.A, like Schoolly D and Ice-T before them, rapped about doing gangster shit; one of their first singles was 1988's "Gangsta Gangsta." N.W.A and their contemporaries never used "gangsta" as a genre name; they preferred to talk about what they did as "reality rap." But you couldn't start a moral panic by talking about reality rap. With "gangsta rap," the Newsweek editorials practically wrote themselves.

The moral panics probably started with N.W.A, who found nationwide cult fame by rapping bluntly and forcefully about drugs and sex and violence and hating cops. That panic got louder after Ice Cube left N.W.A and positioned himself as a cold-blooded rap revolutionary. At the end of 1992, shortly after N.W.A splintered, Dr. Dre, another former member, released The Chronic, an irresistible widescreen blockbuster that effectively turned reality rap into pop music. Dre and his Death Row comrades did nothing to water down their music, and the sheer magnetism of their sound made them pop-chart fixtures. "Nuthin' But A 'G' Thang," the lead single from The Chronic, got as high as #2 on the Hot 100. (It's a 10.) But Dre made unreconstructed street music, and it didn't get the kind of radio airplay that its sheer popularity warranted at the time. For a long while, Dre and his Death Row labelmates couldn't make it all the way to #1. (Dre and a couple of other Death Row artists will eventually appear in this column.)

By 1995, a few rap songs had managed to top the Hot 100, but all of those conquering hits were novelty songs in one way or another. Vanilla Ice and Marky Mark were goofy white boys making dance-rap. PM Dawn were starry-eyed, melody-loving neo-hippies. Kris Kross were little kids who wore their clothes backwards. Sir Mix-A-Lot liked big butts, and he could not lie. None of those artists had much to do with the violent and profane near-nihilism that had come to suffuse a huge part of the rap landscape. For the moment, that stuff was too harsh for pop radio. That finally changed when Coolio, a Compton rapper who'd gotten famous by making a funky good-time variation on Dr. Dre's G-funk, recorded a sweeping, gothic street-life lament over a Stevie Wonder sample, and when that street-life lament became the theme for a hit movie.

Coolio didn't use cuss words on "Gangsta's Paradise," and he didn't really glamorize the criminal life. Instead, he delivered weirdly catchy street confessions over a melody that plenty of radio programmers would've recognized. Coolio's "Gangsta's Paradise" became a global phenomenon. In the process, it acted as a crucial bridge record. Coolio never made another #1 hit, but a few unflinching street-rappers soon followed him to the top of the Hot 100.

Coolio was born Artis Leon Ivey, Jr. in Compton. (When Coolio was born, the #1 song in America was Jan And Dean's "Surf City.") Coolio was a sickly kid with bad asthma, but as he got older, he started running with local gangbangers, and he spent a few months in jail for larceny as a teenager. Later, Coolio studied at Compton Community College and discovered rap. He took his stage name from Julio Iglesias, and he released a couple of local singles, but a cocaine addiction derailed his career. Later on, while straightening himself out, Coolio worked as a firefighter and a security guard.

In 1990, Coolio joined South Central LA rapper WC, formerly half of the '80s duo Low Profile, in a new group called WC And The Maad Circle. Coolio was all over the Maad Circle's 1991 debut album Ain't A Damn Thing Changed, a minor West Coast classic, and he rapped on the single "Dress Code." (The Maad Circle's highest-charting single, the 1995 Ice Cube/Mack 10 collab "West Up!," peaked at #88, but Coolio wasn't in the group anymore by then. As a solo artist, WC's highest-charting single is 1997's "Just Clownin'," which peaked at #56. As a third of the supergroup Westside Connection, WC got to #21 with the fuck-somebody-up 1996 classic "Bow Down.") The Maad Circle toured with Ice Cube, and one night at First Avenue in Minneapolis, the group rushed out into the crowd and beat the shit out of the soundman. For a while, Coolio was probably more famous for his role in that fracas than for any of the music that he made.

After Ain't A Damn Thing Changed, Coolio left the Maad Circle and joined another crew called 40 Thevz. In 1994, Coolio signed a solo deal with Tommy Boy, and he released his debut album It Takes A Thief. That LP's big single was "Fantastic Voyage," a goofy and friendly take on West Coast G-funk that became an unexpected crossover smash, thanks in part to a cartoonish video from director F. Gary Gray. Coolio's distinctive hairstyle -- braids twisted up so that they'd shoot in every direction -- probably helped, too; it made Coolio one of the few rappers who could be identified by silhouette alone. "Fantastic Voyage" peaked at #3, and it pushed It Takes A Thief to platinum sales. (It's a 7.)

Before "Fantastic Voyage," Coolio was one LA rap journeyman among many. After "Fantastic Voyage," he had a name, and plenty of the musicians in his scene wanted to work with him. At the time, Coolio's manager Paul Stewart was roommates with a producer named Doug Rasheed. Their house had a recording studio, and it became a hub for rappers from that scene. One of Rasheed's collaborators was Larry "LV" Sanders, a singer who was part of South Central Cartel, a rap group with a Def Jam deal.

One day, while putting together beats, Doug Rasheed pulled out his copy of Stevie Wonder's 1976 blockbuster masterpiece Songs In The Key Of Life and went to work on "Pastime Paradise," a deep cut that had never been released as a single. "Pastime Paradise" had been a hugely advanced track in its day. Wonder built the song with synthesizers, using them to mimic the sound of the string section that he could've easily afforded to hire. In its original form, "Pastime Paradise" is a lament about the people who idealize the oppressive past. Wonder makes it sound bleak and epic, and as the track builds to its finale, he harmonizes with a wailing gospel choir.

When Doug Rasheed sampled "Pastime Paradise," he took it to LV, who was trying to get a solo deal at the time. LV sang over the track, using Stevie Wonder's melody but singing about a gangsta's paradise instead. LV wanted a rapper to join him on the song, and he offered it to fellow South Central Cartel member Prodeje, who declined. But while they were working on the song, Coolio stopped by the house to pick up a check from his manager, and he heard what they were making. It transfixed him immediately. In a 2015 Rolling Stone oral history, Coolio remembers essentially demanding to take the track for himself: "I walked into the studio and asked Doug, 'Wow, whose track is that?' Doug said, 'Oh, it's something I’m working on.' I said, 'Well, it's mine!'" Since Coolio already had a hit and a name, Rasheed and LV knew that this could turn out well for all of them.

Inspired by that beat, Coolio wrote his "Gangsta's Paradise" lyrics in one sitting. The song is a work of first-person fiction. Coolio himself was past 30 at the time, but his "Gangsta's Paradise" narrator is 23, and he doesn't know if he'll live to see 24. He sees death all around him, and he knows that his recklessness has alienated all the people in his life. He's been blasting and laughing for so long that even his mama thinks that his mind is gone. He tries to explain his circumstances: He can't live a normal life! He was raised by the street!

Sometimes, Coolio's narrator sounds proud and menacing. He's a loc'ed-out gangsta, set-trippin' banger, and his homies is down, so don't around his anger, fool. But when Coolio's narrator takes a look at his life, he's filled with despair, and the knowledge of his own toughness only makes it worse. He knows that he's a seductive figure, and he knows that's a bad thing: "I'm the kinda G the little homies wanna be like/ On my knees in the night, sayin' prayers in the streetlight." As dark as those lyrics might be, they're also catchy, full of memorable little hooks: "Power and the money! Money and the power! Minute after minute! Hour after hour!" It's an easy song to learn, and my entire generational cohort probably still has every lyric committed to memory.

"Gangsta's Paradise" is a stark departure from the party-funk antics of "Fantastic Voyage," and Coolio's delivery is completely different. He raps it in a chesty baritone boom, stretching out his vowel sounds like a preacher, and he sounds more than a little bit like Tupac Shakur, one of the defining West Coast rap figures of that era. (Pac will eventually appear in this column.) Whether or not it's imitation, that delivery locks in nicely with the pounding drama of the "Pastime Paradise" sample. LV's chorus ups the drama even more, as he howls out that slightly-flipped Stevie Wonder hook over wordlessly wailing choirs. There are bigger rap songs than "Gangsta's Paradise," and there are bleaker ones, too. (UGK's "One Day," one of the saddest songs ever written, came out a year later.) But "Gangsta's Paradise" hits a kind of pop sweet spot. It's hard and pathos-riddled enough to sound credible, but it's also big and anthemic enough to echo around a stadium.

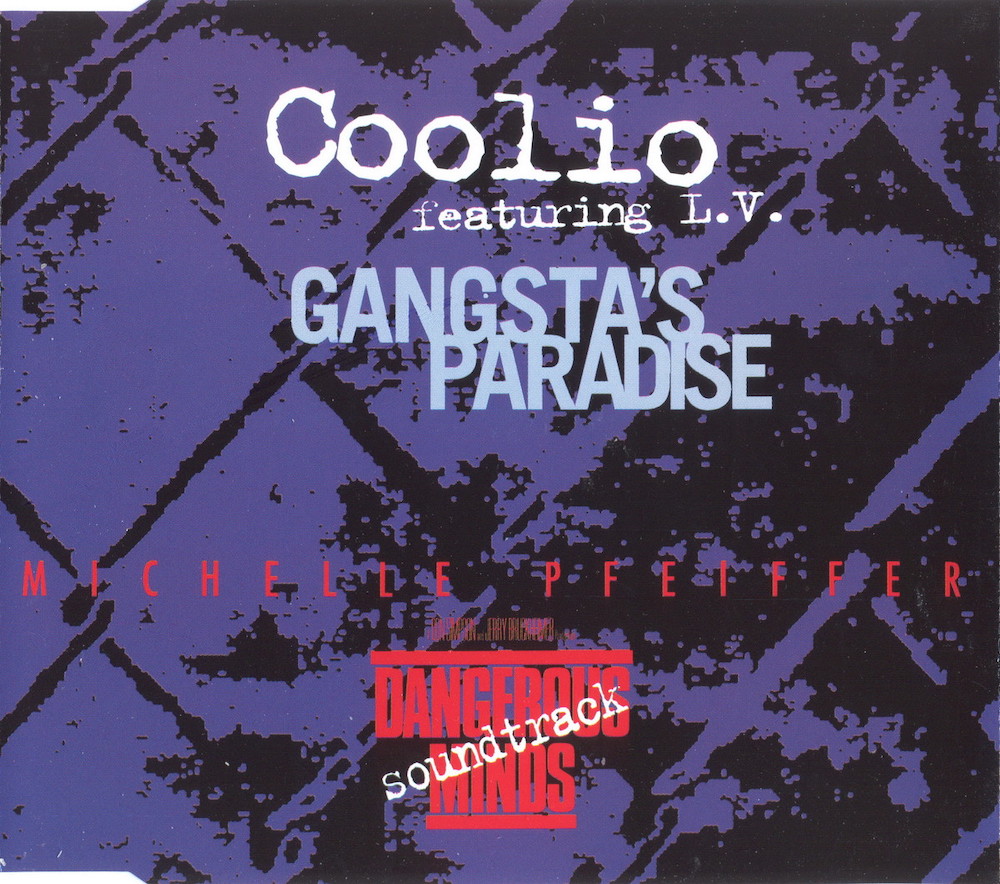

Coolio's A&R at Tommy Boy didn't hear "Gangsta's Paradise" as a single, so his manager shopped it around to different movie studios for soundtracks. It almost ended up in Bad Boys, the hit buddy cop vehicle for future Number Ones artist Will Smith, but it found its way to Disney's classroom drama Dangerous Minds instead. Dangerous Minds is pure cliché-riddled mid-'90s studio fare. Michelle Pfeiffer plays a former Marine who takes a job as a teacher at a tough inner-city high school, and she eventually reaches her hardass students with karate lessons and Bob Dylan lyrics. The higher-ups at the school don't approve of her methods, and one of her students dies tragically, but by the time the movie's over, she's fully bonded with those kids. The film is based on a memoir with the frankly hilarious title My Posse Don't Do Homework, and it's exactly the kind of well-meaning cringey '90s middlebrow fare that nobody really misses.

In the Rolling Stone oral history, Coolio says that Dangerous Minds producers Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer gave him $100,000 for "Gangsta's Paradise," but he first needed clearance from Stevie Wonder for the sample. At first, Wonder turned him down. Wonder didn't want to be associated with gangsta rap. But Coolio had a way to contact Wonder: "It just so happened that my wife, she knew Stevie's brother -- I guess he had been trying to tap that for years." Coolio set up a meeting with Wonder, who said that he could use the sample as long as he took all of his curses off the song. That demand probably helped make "Gangsta's Paradise" much less threatening to pop-radio programmers, and so Wonder probably did Coolio a huge favor there. Wonder's other demand, however, didn't help Coolio too much: "Unbeknownst to me, the other condition was that he wanted 95% of the publishing!"

Once Coolio and Stevie Wonder made a deal, Jerry Bruckheimer decided to make "Gangsta's Paradise" the lead single from the Dangerous Minds soundtrack. This was a good call. The Dangerous Minds soundtrack, like so many other soundtracks from that time, is a weird mixed bag of the rap and R&B of its era. It's got a couple of Rappin' 4-Tay tracks, a solo song from former Guy leader Aaron Hall, and "Havin' Thangs," a minor classic from the New Orleans rapper Big Mike. Missy Elliott's old girl group Sista are on there, and so are Wendy and Lisa, the former members of Prince's Revolution. The album's second single is "Feel The Funk," a pretty generic track from the kiddie-rap group Immature; it peaked at #46.

In the context of that soundtrack, "Gangsta's Paradise" stands out starkly. The song eventually drove the Dangerous Minds soundtrack to the #1 spot on the Billboard album charts and to triple-platinum sales. Jerry Bruckheimer recruited the young music-video director Antoine Fuqua, who was still three years ago from making his own cinematic debut with the not-as-good-as-it-should-be Chow Yun-Fat action flick The Replacement Killers. Later on, Fuqua directed Denzel Washington to an Oscar in Training Day.

Fuqua asked Michelle Pfeiffer to be in the "Gangsta's Paradise" video, and she agreed. Her presence in the video felt like a big deal, and Fuqua made it look slick and intense. The "Gangsta's Paradise" video is pretty much just Coolio and Pfeiffer mean-mugging each other while the camera spins around them, but the two of them make a striking pair, and it looks cool. (Two years later, Coolio had a cameo as a guy who runs street races in Batman And Robin. I guess that means he followed Michelle Pfeiffer into the '90s Batman cinematic universe.)

Bruckheimer and Simpson used that video to heavily market Dangerous Minds, and they put the song in every trailer. It worked. Dangerous Minds got middling reviews, but the film earned about $89 million at the domestic box office. It was 1995's 13th-biggest movie, landing on the year-end box-office list right between Waterworld and Mr. Holland's Opus. "Gangsta's Paradise" got a Record Of The Year Grammy nomination, and Billboard eventually named it the year's biggest hit. ("Gangsta's Paradise" only spent three weeks at #1, but it also racked up nine weeks at #2.) At that year's Billboard Music Awards, Coolio, LV, and Stevie Wonder performed the song together.

Coolio hadn't planned to use "Gangsta's Paradise" on his second album, but when the song blew up, he made it that album's title track. Gangsta's Paradise came out in November of 1995, after the single had already finished its run at #1, and that album eventually went double platinum. (The "Gangsta's Paradise" single, meanwhile, sold three million copies.) Coolio followed "Gangsta's Paradise" with the significantly sillier single "1, 2, 3, 4 (Sumpin' New)," which peaked at #5. (It's a 6.)

After "Gangsta's Paradise," Coolio fell out with Doug Rasheed and LV, and LV recorded his own solo version of "Gangsta's Paradise." (As lead artist, LV's highest-charting single is 1995's "Throw Your Hands Up," which peaked at #63.) Coolio did the theme song for the Nickelodeon show Kenan & Kel, and he followed Gangsta's Paradise with his 1997 album My Soul. It went platinum, and lead single "C U When U Get There" peaked at #12, but that apparently wasn't enough for Tommy Boy. The label dropped him soon after.

Since My Soul, Coolio has been cranking out music on indie labels, and he's been a regular on reality shows: Fear Factor, Celebrity Big Brother, Wife Swap. He had an online cooking show for a little while, and he wrote a cookbook. He's also been arrested for a few times, including for cocaine, his old addiction. But since "Gangsta's Paradise" topped charts around the planet, Coolio never stops getting booked for shows.

Coolio isn't a one-hit wonder, but he never really became an A-list star, either. "Gangsta's Paradise" is a bit of an anomaly -- a breezy party-rapper scoring a massive earthshaking hit with a downbeat ode to the dangers of street life. In its time, though, "Gangsta's Paradise" was probably the most credible rap song ever to top the Hot 100, and the track's success opened things up. In the years that followed, the rap songs that reached the Hot 100 weren't the bright, friendly hits of the early '90s. They were rougher and grimier, and Coolio had something to do with that transition. We won't see Coolio in this column again, but a rappers that we will see probably owe Coolio some minor debt of gratitude.

GRADE: 8/10

BONUS BEATS: You get zero points for guessing that "Weird Al" Yankovic would appear in this section. In 1996, Yankovic released his "Gangsta's Paradise" parody "Amish Paradise." Yankovic had a policy of asking artists for permission before spoofing their songs, but he went through Coolio's label, not through Coolio himself, and Coolio later said that he was mad about the parody. (It probably didn't help that Yankovic copied Coolio's hairdo on the cover of his Bad Hair Day album.) Yankovic apologized, and he and Coolio are cool now. In the Rolling Stone oral history, Coolio says that objecting to "Amish Paradise" is "one of the least smart things I've done over the years." Since then, Yankovic always goes directly to artists, rather than going through intermediaries. Here's the "Amish Paradise" video, where The Brady Bunch's Florence Henderson plays the Michelle Pfeiffer role:

("Amish Paradise" peaked at #53. "Weird" Al Yankovic's highest-charting single, 2006's "White & Nerdy," peaked at #9. It's a 7.)

BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's Bubba Sparxxx flipping the "Gangsta's Paradise" beat on his 2006 Sleepy Brown/Duddy Ken collab "That Man":

(Bubba Sparxxx's highest-charting single is the 2006 Ying Yang Twins collab "Ms. New Booty," which peaked at #7. It's a 6. As lead artist, Sleepy Brown's highest-charting single is 2004's "I Can't Wait," which peaked at #40. As a guest hook-singer, Sleepy Brown will eventually appear in this column.)

BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's the scene from the 2011 Michel Gondry film The Green Hornet where Seth Rogen and Jay Chou rap along with "Gangsta's Paradise":

BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's "Gangsta's Paradise" soundtracking an attempted-heist scene in the 2013 Michael Bay movie Pain & Gain:

(Mark Wahlberg has already been in this column.)

BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's the dance scene from Trish Sie's 2014 motion picture Step Up: All In that's partially set to an EDM remix of "Gangsta's Paradise":

THE 10S: The Luniz' weightless, hypnotic smokers' anthem "I Got 5 On It" peaked at #8 behind "Gangsta's Paradise." I got 10 on it.