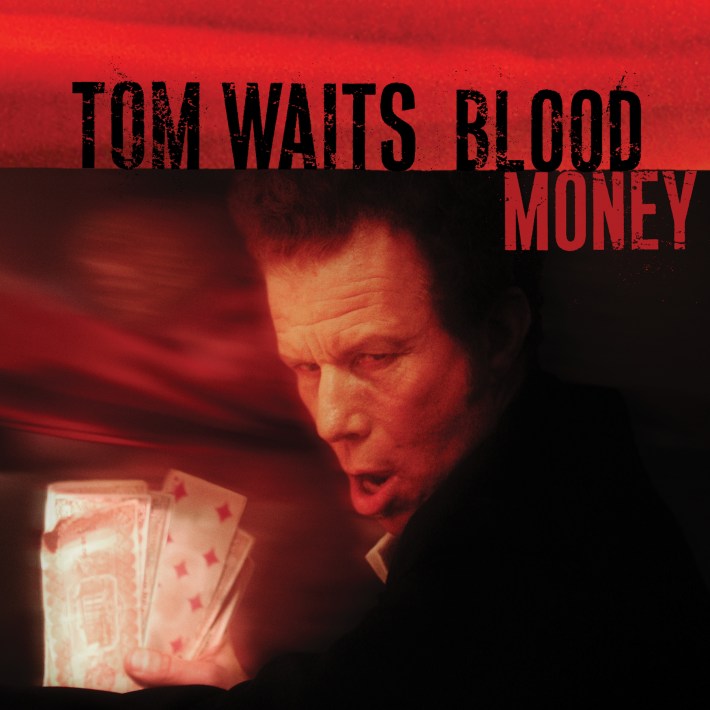

- ANTI-

- 2002

I've been at this game a long time. My first paid byline was in 1996. And in the last quarter century, I've interviewed a lot of musicians, some underground or up-and-coming, some "jazz famous," and some very famous indeed. I always feel a little bit nervous going into an interview, but preparing to talk to Tom Waits in the spring of 2002 was nerve-racking.

I had heard Rain Dogs and Franks Wild Years in high school, and Bone Machine (still his best album) in my early twenties, and I thought he was an absolute genius: a fantastic lyricist, a unique performer, and a conceptualist unlike anyone else in pop music. Waits' albums were portals into an alternate universe America that had more in common with the poems of Charles Bukowski and the novels of Harry Crews than the world I saw out my window. And although I listened a lot to his major albums -- the ones listed above plus Swordfishtrombones and Mule Variations -- I hadn't read many interviews with the man. I had the impression that he didn't like doing press, that he'd prefer to let the albums do the talking.

And indeed, when my phone rang at the appointed hour, it was immediately obvious that this was going to be a performance, with me as his scene partner. I once interviewed the late Dave Brockie, aka Oderus Urungus from GWAR, and when he picked up the phone, he asked me, "Do you want to talk to Dave, or do you want to talk to Oderus?" I opted for Dave, but Waits didn't make the same offer. He was in "Tom Waits" mode from the moment I said hello. I'd ask him about songwriting, or production, and he'd give me a wry, somewhat surrealistic one-liner or aphorism that contained a little bit of insight, but if I asked him something he didn't want to discuss, he'd tell me a weird fact about bears or some exotic insect from South America. It was fun, but I came away thinking I didn't know any more about the actual man named Tom Waits, or his art, than I had before we'd spoken.

But then something strange happened. Twenty-four hours later, Waits called me back. It turned out that he wanted to clear a few things up. Specifically, he wanted to talk more about his creative partnership with his wife, Kathleen Brennan, who's been his artistic soulmate and co-writer since they married in 1980. That second conversation wound up being just as long as the first, and much more interesting.

"When it comes to ideas, what you should do here, what you should do there... she knows a lot, and she's the only one of us that knows how to read music," he said. He didn't even seem to think he could write without her if he tried. "When it comes to who does what, we kind of throw it all in the pot, I guess. But when you locate certain things in the music, whether it's the meadow or the cruise ship or the dive or the rapture or the clouds or whatever it is, it's something that you kind of share evenly, you know. Alice and Blood Money are kind of like twins, or like Cain and Abel a little bit, and we wrote and recorded them together and endured the arduous process of recording these things together, which is a long process."

Waits didn't reveal his deepest secrets to me on that second call, or anything like that, but he was much more willing to talk about his methods, and the thinking behind some of his choices. For example, the second track on Alice, "Everything You Can Think," opens with the sound of a steam locomotive, but it's not a pristine digital sample from a sound effects library; it's taken from a crackly LP. "It's like knocking things out of focus just a little bit, just enough," he told me. "I love hearing that. It's interesting how it's something that everyone used to complain about with records. 'Don't scratch your records, keep 'em clean,' and all that. But now it's become part of the journey back, in order to spin the part that we bring forward with us."

Alice and Blood Money were released simultaneously on May 7, 2002 -- 20 years ago this Saturday -- but they were written almost a decade apart. Alice was originally a play which capped off an extraordinarily busy year for Waits. He released the almost entirely instrumental soundtrack to the Jim Jarmusch movie Night On Earth in April 1992, followed by Bone Machine in August. Alice, his second collaboration with avant-garde theater director Robert Wilson, premiered at the Thalia in Hamburg, Germany in December.

Waits and Wilson had previously worked together in 1989 on The Black Rider, based on a German folktale -- author William Burroughs also contributed to the libretto. When we spoke, Waits described Wilson, whose productions are weirdly lit and glacially paced, as "one of those innovative guys that's more like a surgeon or an inventor. He slows everybody down so it's like an underwater ballet." See what I mean? Evocative, but veiled.

Alice was based on the relationship between grown man Charles Dodgson (aka Lewis Carroll) and Alice Liddell, the neighbor girl who was his inspiration for Alice's Adventures In Wonderland. The songs Waits wrote are a mix of declarations of doomed love, observations of a fallen world, and pieces describing freaks and deformed people ("Table Top Joe," "Poor Edward"). He actually lost them after the play's premiere; his car was broken into in 1992, and a CD of demos was stolen and widely bootlegged. Supposedly (with Waits, every story should begin with "supposedly"), he had to buy a copy himself years later, to rework them for the final album.

The music, in its officially released form, has some of the junkyard qualities of everything he's done since the early '80s, but it's dominated by dark, late-19th/early-20th century European sounds. The influence of Kurt Weill on the songs is obvious. There's a lot of French horn in the arrangements, and a lot of Stroh violin, a 19th century instrument with an attached horn allowing string players to be heard over an orchestra's brass section. Many of the tracks sound like an operetta recorded on period instruments. It's Waits' least "rock" album by far, and filled with melancholy and loneliness.

Blood Money was also the soundtrack to a theater piece. Waits' third (and, to date, final) collaboration with Wilson was an adaptation of playwright Georg Büchner's Woyzeck, which he left unfinished at his death in 1836. Like Alice, it was based on a true story: a German soldier murdered a woman with whom he'd been living, in a fit of jealousy. In the play, the soldier is humiliated by his superior officer and subject to medical and psychological experiments that drive him insane. Meanwhile, his girlfriend (and the mother of his child) is cheating on him. Eventually, he kills her. The story's been adapted and presented many times, most notably as an opera by Alban Berg and a movie by Werner Herzog, starring Klaus Kinski as Woyzeck. The Wilson version premiered in 2000, and when Waits decided to release the songs as an album, he figured Alice deserved to be out in the world, too. As he put it to me at the time, "I'm just glad to have all these people out of my head that weren't paying rent. I'm tellin' 'em, ‘Go on out there and make Dad some money.'"

Blood Money sounds more like a typical Tom Waits album than Alice. The arrangements feature his latter-day palette of guitar, bass, drums, piano and horns, plus various clattering percussion devices -- musically and sonically, it sits comfortably beside Rain Dogs or Bone Machine. And removed from their dramatic context, the songs stand up quite well. Several of them are about how everything sucks ("Misery Is The River Of The World," "Everything Goes To Hell," "God's Away On Business"), while others are declarations of doomed love ("Coney Island Baby"). There's one song, "Calliope," that features the titular instrument, typically heard at carnivals. Waits bought himself one, and seemed to really enjoy telling me about it.

"It's got 57 whistles. The sound is incomparable. You can scream right at the keyboard of a calliope and not be heard... There's a motor in another room. Actually, a background in car repair is gonna help you more in working on a calliope than a background in music... I'm not allowed to play it around here. I have neighbors. It's like a car up on blocks right now."

Alice and Blood Money were recorded together, with the same pool of musicians, but they're completely different albums. And over the years, I've gone back and forth on which one I like better. In 2002, I thought Alice was more interesting, just because its Weimar atmosphere was atypical for Waits, but over time, the songs from Blood Money are the ones that have stuck in my head. He delivers some really brilliant vocal performances on it, too -- he sounds like Leonard Cohen on "Everything Goes To Hell," and like Rowlf the Dog on "Coney Island Baby." And "Knife Chase" is one of the best instrumentals in his catalog.

It's not at all surprising that Waits has had such a successful career in the theater (and in movies). He's an actor playing a singer-songwriter; "Tom Waits" is a character, one he plays every time he steps into the world in a professional capacity. Preserving the integrity of that character -- committing to the bit, as comedians say -- is crucial, which is why he and Brennan have a hard-earned reputation for being intensely private about their real lives. And it's why his explicitly theatrical/conceptual albums (Franks Wild Years, The Black Rider, Alice, and Blood Money) sit so comfortably alongside the ones that are supposedly "just" collections of songs. Because even on his "regular" records, he's playing a character.

The idea of authenticity in music is bullshit. Just writing a song about something is artifice. But pop listeners have been programmed to read lyrics as autobiography (call it "Taylor Swift syndrome," though she's far from the only one playing the game). Waits rubs the listener's face in the artifice, writing songs that are explicitly "in character" or about other people -- the original song "Frank's Wild Years," from 1983's Swordfishtrombones, is a story about a guy who can't handle his quiet suburban life, so he burns his house down and drives away. Four years later, that short story became an entire play. Waits is music's ultimate unreliable narrator, a carnival barker luring you into the tent with the promise that you'll get much more than you eventually do. And ironically, that's one of the reasons his records are as captivating as they are. He makes you want to believe.