- Interscope/Geffen

- 2002

Regardless of era -- and there are many at this point -- Weezer might be the most confounding rock act of the 21st century. The more insight you try to gain by reading old album reviews and interviews with Rivers Cuomo (or even newer ones, for that matter), the more your brain starts to feel like a martini shaker. Reading this 2002 SPIN cover story, I'm suddenly reminded of a boss I once had who was one of the smartest people in the room, and he knew it. In conversation with him, It didn’t matter how sure you were of your feelings on any subject -- he could verbally twist any cogent line of thinking (and look totally harmless while doing so in a mussed-up hoodie and five o’clock shadow) until you started questioning the nature of your own reality like a Westworld robot. In Weezer's Maladroit era, Rivers Cuomo reminds me a lot of that guy.

Let me backtrack by saying that Maladroit, Weezer's riff-packed fourth album, has been rightly embraced by history as the band's most heavily underrated project, and possibly its most divisive. In 2002, it followed Weezer's blatantly polarizing self-titled, aka "The Green Album," which I don't need to remind you was a deeply intentional pivot away from the heart-in-a-blender Pinkerton. After a whiplash like that, I wouldn’t blame anyone for not quite knowing how to absorb Maladroit when it came out. Nor would I blame anyone for letting it Homer Simpson Into The Bush years later.

I will admit to not knowing what to make of Maladroit in 2002. I have a vivid memory of buying the album the week it dropped -- 20 years ago this Saturday -- racing home, closing the door, hitting "play" on my CD player, and waiting to have my hair blown back. (I liked "The Green Album." I also liked Pinkerton. I was a real swing voter.) My hair wasn't blown back. I don’t remember loving Maladroit; I mostly remember confusion. The album had precious few cheery nerd-rock anthems a la "Buddy Holly" and no isolationist ruminating on the wavelength of "The World Has Turned And Left Me Here." There were no burned-out blasts about being "Tired Of Sex" with groupies or whines about isolation or falling for underage Japanese fans or LGBTQ+-identifying women. As a middle-school student who shamelessly loved 'NSYNC and the Backstreet Boys, and was a huge "Green Album" fan with zero qualms about that, I personally would've been open to another one of those. But the vibe shift Maladroit gave -- walls of guitar-solo cheese referencing rock eras I had not yet cared to indulge in -- I didn't know how to absorb that. I think I listened to Weezer’s fourth record a few more times and then retreated back into the comfortable, familiar arms of their first three.

Listening to Maladroit 20 years after its release offers a vastly different experience because we have so much more perspective. The self-produced Maladroit continues Weezer's interest in hooks and only hooks, but diverges from "Green" by upping the distortion and going full-on, cartoonishly rawwwwwk across the album's 13 tracks. Maladroit, like its predecessor, portends a two-decade future of aggressive mediocrity laced with moments of brilliance. It is, like Weezer's bespectacled leader, brimming with ideas and frustrating contradiction. It is the first album to feature bassist Scott Shriner (who replaced the late Mikey Welsh, who replaced Matt Sharp) and marks a fascinating moment where Weezer embrace a punk/DIY ethos by sharing Maladroit’s songs on their website as it was in production, much to their label's chagrin.

Even if Geffen Records wasn't happy about Weezer sharing new music free of charge on the still-young internet, the strategy did show how much the band understood their fan base, who spent ample amounts of time debating their work on message boards, both official and unofficial. As that 2002 profile reminds us, Weezer's fans have always been extremely engaged and outspoken. Tossing their new material out like feed in a chicken coop was a really forward-thinking move considering the various ways bands would go on to cut record labels out of the equation. So was using that process to partially crowdsource the tracklist; a 2000 track called "Slob" made it onto Maladroit at fans' urging. It's easy to see why listeners would've rallied for that cut: "Slob" marks an especially vulnerable point on an otherwise surface-y album where Cuomo is feeling agoraphobic, lashing out: "Leave me alone/ I won't pick up the phone/ And I won't listen to messages/ Sent by someone who calls up and says/ I don't like how you're living my life."

A May 2002 Guitar World interview with Cuomo reflects the frontman's beyond-complicated (to say the least) relationship with his fans, where he tells the interviewer: "Most of the time I'm a pretty cool character." Regarding the fact that his fans may expect him to be "distraught" more often than not, he really goes off:

Cuomo: Yeah, I think most of them would be shocked if they met me, because I'm pretty bland.

GW: Sometimes when you meet the fans, do you feel that they're disappointed because you're even-keeled?

Cuomo: I never meet fans.

GW: You never meet them?

Cuomo: Never. I like talking to them over the internet, but that's it.

GW: You guys don't do in-store record singing or after-show meet-and-greets?

Cuomo: Hell no! Fans are annoying. They all want something.

GW: Whether it be asking you to sign something or expecting you to act a certain way...

Cuomo: Yeah, or asking me to play a certain song. They're all little bitches, so I avoid them at all costs.

I admit, it must be very mentally uncomfy to not only know that you have but to be painfully aware that those fans care A LOT. (That 2018 Weezer-themed SNL sketch with Matt Damon encapsulated this mania perfectly.) Meanwhile, you're the type of person who cares so much that the caring metastasizes to build a tumorous wall that fortifies your heart against any and all criticism. That just sounds like a really awful way to live. No wonder Cuomo went into a self-imposed exile -- the stuff of indie-rock legend at this point -- after Pinkerton got panned upon release.

So it appears that Cuomo developed -- or always had -- a severe love-hate relationship with his followers, valuing their input enough to let it influence Maladroit’s tracklist but dubbing most of their choices "whack" to his A&R guy. (Again, what a lonely existence, being the smartest person in that proverbial room.) Cuomo was similarly at war with his label, Geffen/Interscope, who asked that radio stations not play any songs sent from Weezer until a formal release. It was also around this time that former bassist Matt Sharp sued the band, alleging that he was owed money for his contributions to their self-titled debut ("The Blue Album") and Pinkerton. Cuomo said the accusations were "completely without merit," but he still settled out of court.

In terms of actual album content, Maladroit is so much better than most remember. It's a peculiar kind of aging, and what you think of the album may have everything to do with how old you are. For those '90s die-hards who won't accept anything after Pinkerton, Maladroit represents a broken, unacceptable band on a perma-decline. For the younger sect -- say, anyone born in or after the '90s -- Maladroit is early enough in Weezer's overall catalog that it represents an acceptable entry point before things got really bad. (To be fair, lots of people do legitimately enjoy their latter- and present-day material too, and Maladroit probably sounds like a masterpiece to those people.)

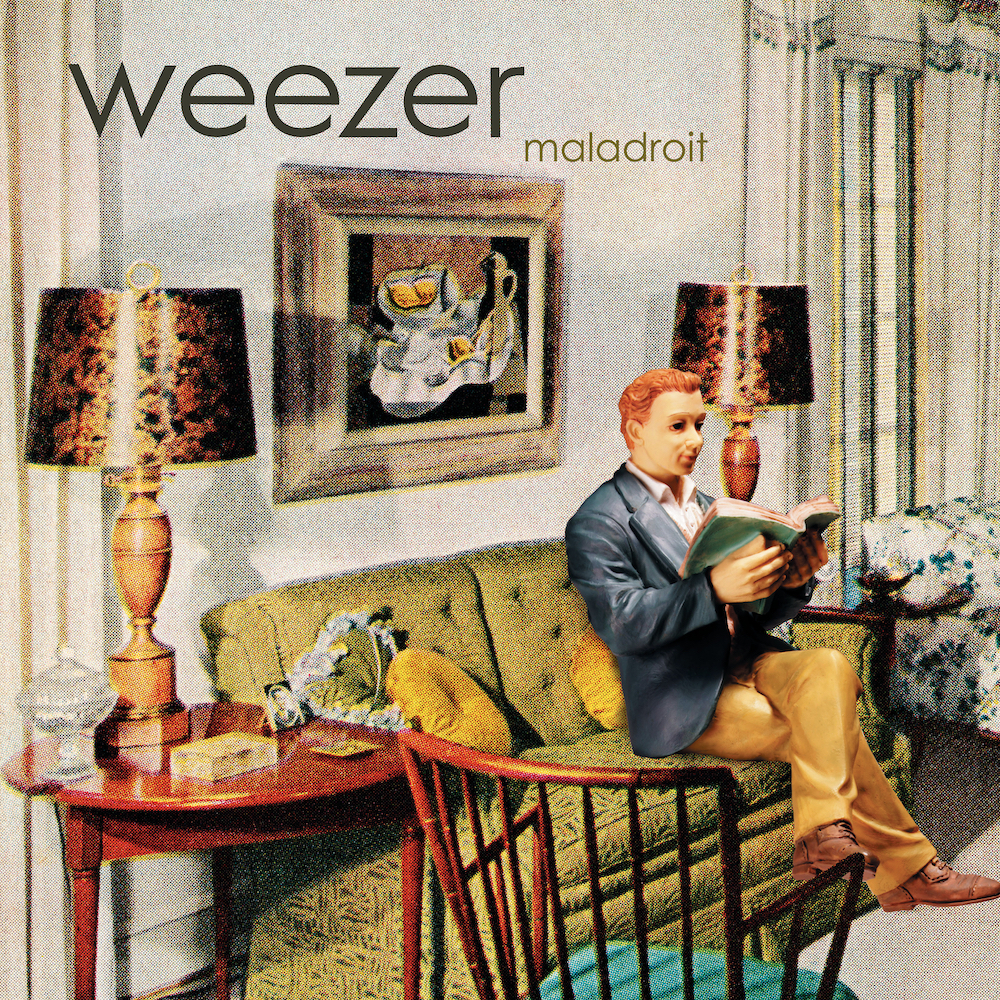

If we can just divorce Maladroit from the layers of lore, I think we'll find that it's a highly enjoyable, well-produced, constantly catchy affair. It openly embraces a heavy-metal edge without sacrificing pop sensibility. Although Cuomo was singing about Ace Frehley and Peter Criss all the way back on Weezer's debut, Maladroit marks the first time the band's well-documented love of '70s and '80s riffers like Kiss, Metallica, and Van Halen is just as represented in the songwriting as their foundational affection for the Beach Boys, the Cars, and Cheap Trick. More than anything, it marks a powerful outreach to fans, for better or worse. In addition to sourcing opinions around mp3s, Weezer hosted a submission contest to decide on the album’s cover and got the title from a suggestion on the message boards. As a thank you, fans were rewarded with a special thank you in the album's liner notes.

Ironically, the album’s contents are the least agreed-upon in the band's entire catalog, which, if nothing else, says a lot about what happens when self-proclaimed underdogs become rock gods in a sellout-anxious era. Lead single "Dope Nose" comes out of the gate with a blast of call-and-response chants overlaid with arena-filling guitar. Lyrically, there is a case to be made that "Dope Nose" is Cuomo admonishing fans, essentially telling them to lighten up about his lightening up: "For the times/ That you wanna go and bust rhymes real slow/ I'll appear/ Slap you on the face and enjoy the show."

The record's standout single, naturally, is "Keep Fishin'," a "Buddy Holly"-esque callback to Weezer's earliest work, ostensibly about a slothing love interest who needs to figure their stuff out. The darker content in "Keep Fishin'" is glossed over with a power-pop melody and a completely endearing music video starring the Muppets. Looking back, it's tricky to tell whose idea it was to bring the Muppets into the fold -- was it the band's? Or the video's director Marcos Siega? It proved a brilliant move, with Weezer playing musical guests on The Muppet Show while drummer Patrick Wilson is held hostage as Miss Piggy's latest love slave and is set free by the Swedish Chef. The band even participated in an MTV Making The Video episode where Pepé The King Prawn takes full credit for having Weezer on and admonishes them for offering sarcastic answers to his questions.

"Keep Fishin'" was such an overarching presence, between the single's radio-friendly nature and its history-making music video, Maladroit didn’t need more than two singles to make a zeitgeisty splash in 2002. The Muppets were even licensed to help market Maladroit on a wider scale, with Kermit The Frog and various other characters in Weezer T-shirts splashed on every image of the band around that time. This no doubt helped make the band appear more likable in general -- Cuomo is not exactly loquacious in his TV interviews, of which there are very few to begin with.

Across the remainder of Maladroit, you have a metal-funk romp like "Burndt Jamb," which rocks a lot harder than I remembered, the excellently yearning "Slave," and the affirmation-filled "Love Explosion," which reads like a note from Cuomo to himself re: those pesky, opinionated fans: "Take a load off and bow down/ To the others, they love to call you their names/ They've been wanting to kill you in your sleep."

It’s worth noting that there is a ton of overlap between the recording of Maladroit and its eventual follow-up, 2005's Make Believe. The band went ahead and shared numerous "A5" demos to their website -- and proceeded to scrap all of them and start over. Though Maladroit stands alone and is possibly forgotten in the greater Weezer milieu, it reaches back and forward all at once. Its inherent experimentalism and moments of raw honesty liken it to Pinkerton, but its pop highs portend future mega-hits like "Beverly Hills" and "Pork And Beans." Weezer will never make another album like it again (the more straightforwardly arena-rockin' Van Weezer doesn't count), if only because Cuomo, now firmly middle-aged, is much more at peace with his band's tumultuous history. Being the smartest person in the room is overrated, anyway.