February 28, 1998

- STAYED AT #1:2 Weeks

In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

"I had fully armored myself against having to be crushed by the presence of Céline Dion, but she was the nicest person I’ve met in a while." That was Elliott Smith, the beloved late singer-songwriter, talking to Rolling Stone in 1998. The mere fact that Elliott Smith had been in the presence of Céline Dion was a crazy accident of fate. These days, we're used to seeing indie buzz bands on TV; people jump straight from college radio to The Tonight Show all the time. In 1998, this was not the case. When Elliott Smith sang "Miss Misery" at the Oscars, it seemed deeply improbable -- this paragon of a fragile underground going up to sing his song on the biggest stage imaginable.

Smith had contributed "Miss Misery" and a few other songs to the soundtrack of Good Will Hunting, a not-huge prestige movie from the arthouse auteur Gus Van Sant. Good Will Hunting went on to become a massive surprise hit and an awards-show darling, and it launched Matt Damon and Ben Affleck straight into superstardom. When Smith got nominated for the Best Original Song Oscar, the nomination itself felt like an out-of-nowhere victory. But Smith never stood a chance at winning the award. How could he? Céline Dion was right there, and she was singing her Titanic song on a sort of fake ship-deck, amidst clouds of dry ice, with a white-clad orchestra behind her. She was a motherfucking buzzsaw. She was Tom Brady. She was Roman Reigns. If you had even the slightest flicker of hope in your heart that Elliott Smith would leave that night with a statue in his hand, you were a sucker.

Some of us took this personally. Céline Dion, to some of us, was a living avatar of glop-encrusted mainstream baby food. The monoculture still existed, and she was its walking symbol. But Elliott Smith never saw her that way. Here's what Smith said about her: "Afterward, I'd get these indie rock kids saying, 'I can’t believe you had to hold Céline Dion’s hand.' I said, 'I liked holding her hand because she’s a nice person. In fact, right now, you’re being much more narrow-minded and shallow than she is. You’re in a very backward position here. You should rethink it.'"

Elliott Smith was talking about Céline Dion the person, not "My Heart Will Go On" the song, but the same lesson applies to both. Elliott Smith didn't go to the Oscars as a representative of some seething subculture. He went there to sing a song that people liked. When he was at the show, Céline Dion, who must've been plenty nervous herself, helped to make Elliott Smith less nervous. If you like, you can hear "My Heart Will Go On" as a towering example of ugly, schlocky mainstream sentimentality, but what does that help? Especially now that mainstream sentimentality is essentially extinct? Instead, I'd argue that "My Heart Will Go On" is a ridiculous thing that's offered a certain comfort to millions upon millions of people, and that it might one day offer comfort to you, too, if you let it.

"My Heart Will Go On" wasn't supposed to exist. James Cameron, the maniacally obsessive auteur behind Titanic, didn't want a pop song in his movie. Working on Titanic, Cameron made sure he controlled every little thing that was happening. He repeatedly visited the wreck of the real Titanic in submarines, eventually spending more time on the ship than the actual passengers had done. He helped invent whole new cameras that could shoot deep underwater. He drew the basic-ass sketches for Leonardo DiCaprio's character Jack -- the ones that convince Kate Winslet's Rose that he's the next Picasso. Cameron kept that focus on Titanic even as the budget ballooned out of control, making it the most expensive film in history at that point. Even as people predicted massive failure for the film, Cameron kept his hold on Titanic. If he didn't want a pop song for the Titanic soundtrack, there wouldn't be one.

Cameron wanted the mysterious Irish new age musician Enya to score Titanic, but she turned him down. (Enya's highest-charting single, 2000's "Only Time," peaked at #10. It's a 9.) When Cameron couldn't get Enya, he went to James Horner, the veteran film composer who'd gotten a well-deserved Oscar nomination for scoring Cameron's Aliens. Talking to Horner, Cameron made his intentions plain. Titanic was a period piece, and he wanted nothing modern on the soundtrack -- nothing that might take the audience out of the thing's sweep. Horner had other ideas, and he made plans for those ideas in secret.

To that end, Horner went to an old collaborator, the bafflingly successful lyricist Will Jennings. Jennings has written a whole lot of songs with Steve Winwood, including Winwood's chart-toppers "Higher Love" and "Roll With It." Jennings has also been in this column a bunch of times for co-writing grand, hammy ballads: Barry Manilow's "Looks Like We Made It," Joe Cocker and Jennifer Warnes' "Up Where We Belong," Whitney Houston's "Didn't We Almost Have It All." Jennings hadn't seen Titanic; all he had to work from was Horner's description of the story. But Horner had written a love-theme melody that played throughout the film, and that melody was ready to be shaped into pop-song form. Jennings came up with some lyrics, and he had a specific inspiration.

When Jennings wrote the lyrics for "My Heart Will Go On," he was thinking about Beatrice Wood, a California potter who was more than 100 years old. Jennings had met Wood after going to see a documentary about her life, and he was hugely impressed at her vitality. Jennings thought Wood might be something like the older version of Rose, the one that the former silent-film actress Gloria Stuart played in Titanic. From a lyrical standpoint, "My Heart Will Go On" is Rose looking back on her life, remembering her short time with Jack. Jennings' lyrics are terrible -- "Love was when I loved you/ One true time I'd hold to" -- but it's nice to know that he was trying to capture a specific thing when he wrote them.

After they wrote "My Heart Will Go On," Horner and Jennings went to Las Vegas to meet with Céline Dion and her husband/manager René Angelil. They had history. Horner and Jennings had worked together to write "Dreams To Dream," a ballad for the 1991 animated film Fieval Goes West. Céline, who wasn't super-famous yet, had recorded a demo for that song, but it didn't make it into the movie. Instead, former Number Ones artist Linda Ronstadt sang "Dreams To Dream." Céline didn't like "My Heart Will Go On," and she thought she'd already done enough movie themes. She didn't want to record it, but Angelil convinced her to reconsider. So Céline agreed to record a demo of "My Heart Will Go On," laying it down in New York with Horner playing piano. She knocked it out in a single take.

Horner overdubbed an orchestra onto the "My Heart Will Go On" demo, and then he finally brought the song to James Cameron, who'd previously had no idea of its existence. Horner waited for a day when Cameron was in a good mood, and he put the song over the end of Titanic. Cameron had to admit that it worked. Cameron still wasn't sure about using a contemporary song, but "My Heart Will Go On" didn't really sound that contemporary, and he also knew that a big song would help sell the movie -- a crucial thing, since by that point everyone expected Titanic to bomb. Cameron also thought that the lyrics fit the Rose character perfectly. When he finally met Will Jennings and learned that the song's lyrics had been inspired by Beatrice Wood, he was a little dumbfounded. He told Jennings that Wood had been the basis for the character all along. That one-take Céline Dion demo is the version of the song that appeared in the movie.

You already know what happened next. Titanic did not flop. Instead, it became an insane runaway smash, easily the biggest cinematic cultural phenomenon that has happened during my lifetime. It took me weeks to see Titanic. I'd thought it would be melodramatic garbage, but once it started to resonate, I didn't want to be left behind. When I decided that I did want to see it, though, it wasn't that easy. Every single showing near me would sell out almost instantly. Finally, my dad and I went to the theater hours before showtime to buy tickets. We still had to watch the movie while sitting in an aisle, since enough people had bought tickets to other movies and snuck into Titanic instead. That shit went crazy.

A couple of years ago, I wrote an AV Club column on the Titanic phenomenon, but I'm still not quite sure how the whole thing happened. I was right about Titanic being melodramatic garbage, but it's transcendent melodramatic garbage. The movie works as grand-scale spectacle and as operatic romance. The story of Jack and Rose is pretty clearly just a vehicle for Cameron to tell his story about hubris and greed and tragedy and the things that icebergs can do to ship engines, but the love story is what resonated, at least with the kids I knew. People would go see Titanic again and again, sobbing ritualistically over the ending. In retrospect, maybe the whole deal was that we were in a place of national peace and prosperity that felt strange and alien. Maybe things were too comfortable. Maybe people needed to feel something.

If the Titanic love story was a vehicle for all the other stuff that James Cameron packed into the movie, then "My Heart Will Go On" was a vehicle for that love story. The "My Heart Will Go On" melody is threaded all through the film, and it becomes a sort of lullaby mantra. When the end credits finally come in and the actual song arrives, it's almost a delayed-gratification climax, a final reward after we've watched Rose flashing back on her entire life. It's like we're hearing that this lady's heart will go on even after the movie is over. Among my age group, "My Heart Will Go On" resonated hard. I saw kids welling up with tears when the song came on the radio. Maybe "My Heart Will Go On" served the same mass-mourning function as Elton John's "Candle In The Wind 1997," but instead of a real person, people were mourning Leonardo DiCaprio's fictional character.

A few months after the movie came out, my graduating class voted "My Heart Will Go On" as our prom theme. At the prom that year, we all got little candles with the song's title and a boat on them. I thought the whole thing was so stupid. I probably spent years rolling my eyes at "My Heart Will Go On." But over time, I melted.

When I finally accepted "My Heart Will Go On" into my heart, it wasn't Stockholm Syndrome -- or, in any case, it wasn't just Stockholm Syndrome. The song, I came to learn, has absolute confidence in its sincerity. That little flute-whistle calls out mournfully, and Céline Dion answers it with so much softness and warmth in her voice: "Every night in my dreams, I see you, I feel you." The song follows the time-honored movie-ballad arc, building the big finish where Céline Dion howls out the chorus one final time, and it works. On a certain level, the song's drama is irresistible. It demands a theatrical hand-on-heart singalong: "Near! Far! Where-evvvv-er you are!" I put up so many defenses against this thing, but it finally got me anyway. I was not unsinkable.

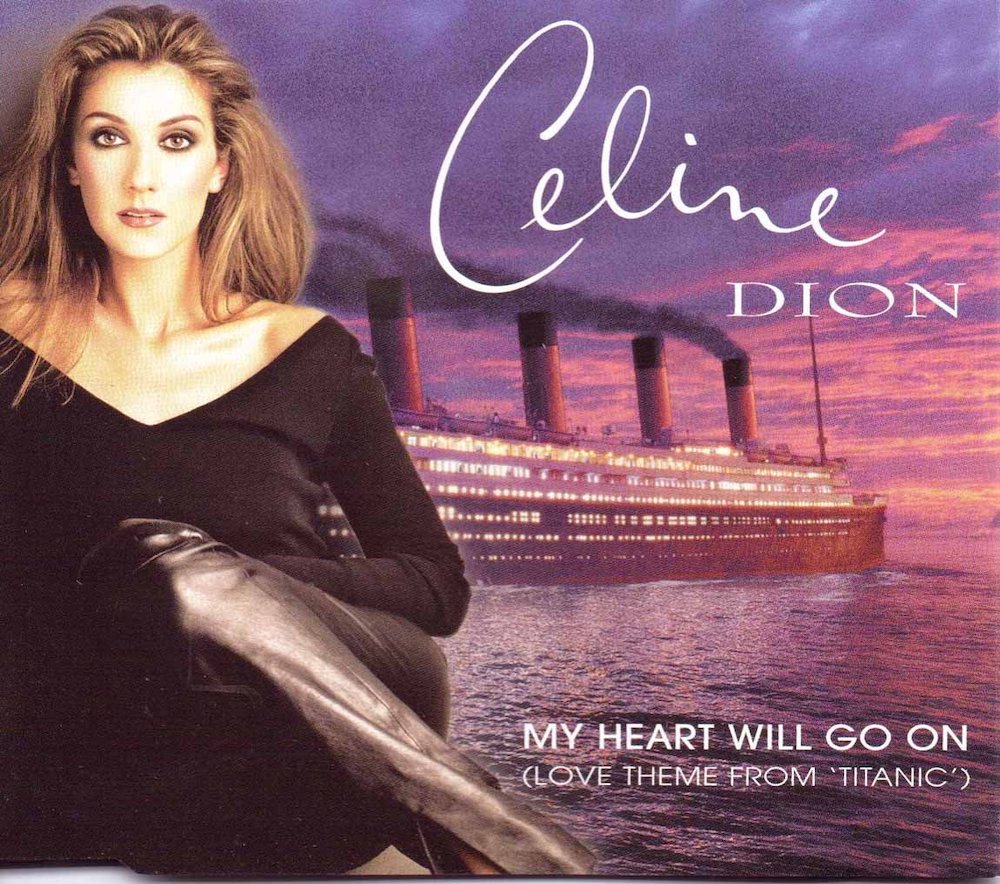

When Titanic was about to come out, Céline Dion re-recorded "My Heart Will Go On" with Walter Afanasieff, Mariah Carey's longtime collaborator. Afanasieff rearranged the song a bit, adding a few hacky pop-song touches. The drums boom a little louder, the backing vocals come in a little bigger, and there's a thoroughly pointless screaming electric guitar in there. That Afanasieff-produced version of the song didn't appear in Titanic, but it did find a place on Let's Talk About Love, the album that Céline released a week before Titanic came out. Céline made a video for "My Heart Will Go On," with future Honey director Billie Woodruff filming her swanning across the deck of the Titanic in a ball gown, with an impossible purple sunset in the background.

In Fred Bronson's Billboard Book Of Number 1 Hits, Afanasieff seems a little sore over his version of the song not showing up in the film: "The one I did is the one that got all the airplay, was released as a formal single, was the one that charted, was the one on Céline's album Let's Talk About Love. It didn't make any sense why the huge #1 worldwide famous song wasn't actually in the movie." Really, though, the version of "My Heart Will Go On" that I always heard on the radio wasn't the official single version. Instead, it was an edit of the song that had dialogue from the movie over all the quiet parts. The song and the film were that tied up with one another.

Let's Talk About Love is a crazy album, an all-over-the-place soft-pop opus that's almost entirely made up of ballads. Céline knew that she was making a blockbuster, so she brought in all sorts of big names. She sings songs with Barbra Streisand, the Bee Gees, and Luciano Pavarotti. Carole King co-wrote one song, and Bryan Adams co-wrote another. Some of the biggest producers in pop history appear in the credits: George Martin, David Foster, Jim Steinman. But since Let's Talk About Love and the Titanic soundtrack both came out at the same time, and since both had different versions of "My Heart Will Go On," Céline Dion was effectively competing with herself on the album charts. For a long time, the Titanic soundtrack was winning.

Titanic opened wide in December 1997, and it remained the #1 movie in America until April. On the album charts, Let's Talk About Love made it to #1 in mid-January, and then the Titanic soundtrack knocked it out of the top spot a week later. The Titanic soundtrack then kept that #1 spot for the next 16 weeks, dominating the album chart deep into May. Keep in mind: The Titanic soundtrack is all orchestral music, with only the one actual song. But that's what people wanted. By April, the Titanic soundtrack had gone diamond. Back To Titanic, a second soundtrack album, came out in October 1998, and that one went platinum. For a minute there, James Horner was something like a pop star.

Let's Talk About Love sold like nobody's business, too. That album eventually went diamond, as well, though it took a little longer than the Titanic soundtrack. The people at Columbia, Céline's label, did not want to cut into her totals, but they also knew that "My Heart Will Go On" was easily the most popular song in America. So they released the song as a single, but they did it strategically. They only printed up about 600,000 copies of the single. Once those were gone, they were gone, and you would need to buy one of the albums if you wanted to own the song. That's why "My Heart Will Go On" was only a #1 single on the Hot 100 for two weeks. Presumably, the song would've held down the top spot for a whole lot longer if they'd kept the single in print.

Maybe that album-sales strategy is why none of the other songs from Let's Talk About Love ever came out as singles. The Barbra Streisand duet "Tell Him" was a pretty big adult contemporary hit, but none of those other tracks got a big push. "My Heart Will Go On" was all that the album really needed. The song won the Oscar for Best Original Song that year, naturally. Titanic absolutely swept the show that year, winning 11 Oscars and tying the record for the most awards for a single film. (Ben-Hur had set the record, and The Lord Of The Rings: The Return Of The King would later make it a three-way tie.) Horner won his first and second Oscars that night, and they were the only Oscars that he would ever win. Jennings and Horner accepted the Best Original Song award from Madonna, who was definitely rooting for Elliott Smith.

"My Heart Will Go On" also won a grip of Grammys, including Record Of The Year and Album Of The Year. Horner, Jennings, and Mariah Carey co-wrote "Where Are You Christmas," from the godawful Jim Carrey How The Grinch Stole Christmas movie; Carey's ex Tommy Mottola, then the head of Sony Music, blocked her version's release during their divorce proceedings, so Faith Hill recorded it instead. (It peaked at #65.) Horner went on to score more big movies: The Perfect Storm, A Beautiful Mind, Cameron's Avatar. He died in 2015 at the age of 61 when he crashed the small plane that he was piloting.

"My Heart Will Go On" is now, for most of us, the Céline Dion song, but it did not mark the end of her hitmaking period. We will see Céline Dion in this column again.

GRADE: 8/10

BONUS BEATS: Here's the scene from the 2009 film Night At The Museum: Battle Of The Smithsonian where the Jonas Brothers, playing CGI cherubs, serenade Ben Stiller and Amy Adams with "My Heart Will Go On":

(The Jonas Brothers will eventually appear in this column.)

BONUS BONUS BEATS: As you might imagine, "My Heart Will Go On" is a frequent target of snotty pop-punk cover versions. Bands like the Vandals and New Found Glory have given it the pop-punk treatment, but if you're going to pick one pop-punk version, it's got to be the one from Me First And The Gimme Gimmes, who turned the track into a sea chanty that sounds a bit like the Dropkick Murphys. Here's their take:

BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: The EDM DJ Steve Aoki has a longstanding habit of dropping a remix of "My Heart Will Go On" into his sets. At a 2017 club gig in Las Vegas, Céline Dion joined Aoki to "perform" the song, and it was absolutely fucking adorable. Here's the video:

(Steve Aoki's highest-charting single is the 2016 Louis Tomlinson collab "Just Hold On," which peaked at #52.)

BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's the bugged-out, synthy power metal version of "My Heart Will Go On" that DragonForce released in 2019:

(DragonForce's only charting single, the 2006 viral hit "Through The Fire And Flames," peaked at #61.)

BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's the wild remix of "My Heart Will Go On" that post-everything mutants 100 Gecs put into the world in 2019:

THE ASTERISK: The fact that the Backstreet Boys have never made a #1 pop hit is one of those truly strange quirks of chart history. Jive, the group's label, willingly gave up at least one shot at the top. The bright shamelessly catchy ballad "As Long As You Love Me" reached #4 on the Billboard Radio Songs chart when "My Heart Will Go On" was at #1. I don't know if "As Long As You Love Me" would've had what it took to reach #1, but since the song never came out as a single, it never appeared on the Hot 100. It's a 7.