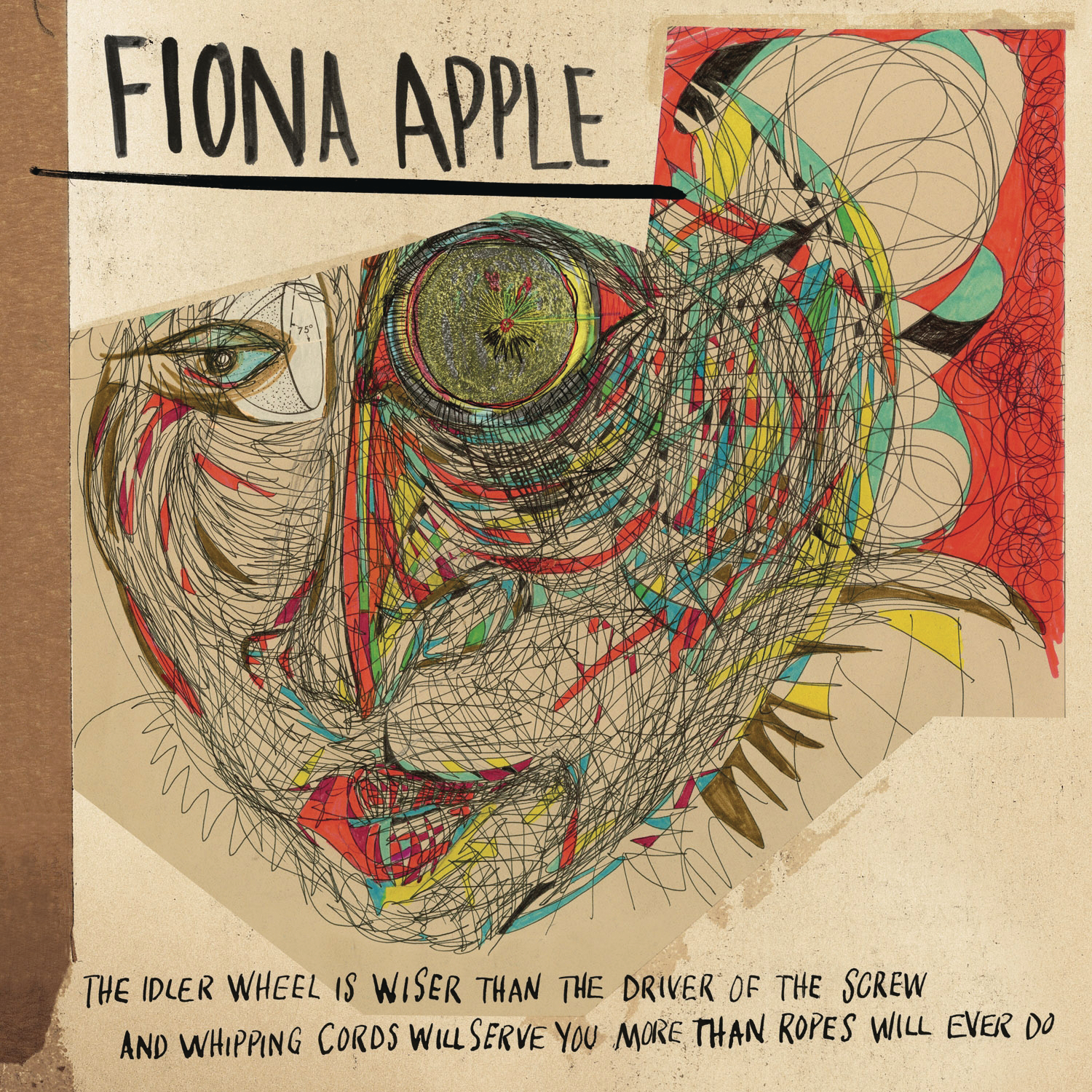

- Epic

- 2012

Seldom seen on social media, Fiona Apple appears warm, answering questions via a Tumblr fan page as part of her occasional "Happy Sunday" videos, which she films when not court watching. In response to the question asking what lyric she is proudest of writing, Apple remarks wistfully that "off the top of [her] head, it's always 'the ants weigh more than the elephants'...because it's true in nature, it's true outside and it's true inside." Citing a TV special by British biologist David Attenborough as inspiration, the line from The Idler Wheel’s "Left Alone" is indicative of Apple's continuous search for truth in a society that is consistently inauthentic.

The Idler Wheel…, which turns 10 this Saturday, battles with this concept but on a more insular level, fully cutting to the core of what it truly means to be human. This body of work really influenced my own introspection and self critique in a way that Apple's previous albums hadn't. As someone born in the 1990s, I missed the first wave of Fiona Apple's career. My earliest exposure to her was when I visited America as a teenager via the most credible source for pop culture comprehension, VH1's I Love The '90s. Focusing on Apple's infamous "this world is bullshit" speech at the 1997 VMAs, something she reflects on in a Vulture interview as "the best thing [she's] ever done," I was instantly dazzled by her astuteness and haven't looked back since. It awoke my inner cynic, an unrelenting critic who would give Jay Sherman a run for his money.

To address it by its Christian name, The Idler Wheel Is Wiser Than the Driver Of The Screw And Whipping Cords Will Serve You More Than Ropes Will Ever Do, puts Apple firmly in the driver's seat, a position that she orchestrated for herself as a consequence of the messy release of its predecessor, 2005's Extraordinary Machine. The 23-word title, taken from a poem by Apple, was ridiculed by some due to its perceived verbosity. "Because that's what you do with me, right?" Apple retorted to the New York Times, fully aware that the metaphor of the 'wise' idler wheel being a reflection of those who "feel everything at once," despite their perceived immobility, would be lost on those who daren't interact with an album title that exceeds three words — unless those words are "The Very Best Of."

It's by no means an easy listen, even disconcerting at times. The lead single "Every Single Night" is a challenge compared to some of her earlier crossover hits such as "Criminal" and "Paper Bag." Despite the foreseen sneering, reviews at the time were almost overwhelmingly positive, suggesting it was worth the seven-year wait. Stereogum rated it the year's best album, while Consequence regarded it as "one of the most daring pop records in recent history."

Such plaudits were impressive even by Apple's standards, though this acclaim was to be eclipsed by the follow-up, 2020's Fetch The Bolt Cutters. I would argue, however, that Fetch The Bolt Cutters would not be met with such resounding praise without its older sister. The Idler Wheel... whet the appetite of those eager to dive headfirst into the complexities of the human psyche and provided levels of critical thinking that made it just about possible to cope with the malaise that comes with navigating a post-Trumpian world. Apple defiantly expressed that the process of making the album was to echo the sentiment: "I'm in charge, I can do whatever I want." Even the label bosses at Epic Records were kept in the dark until she presented it to them in 2012, despite recordings going back to 2008 or 2009 — Apple herself is admittedly unsure.

Electing to work alongside her touring drummer, Charley Drayton, credited as "Seedy" to Apple's "Feedy" — as opposed to her usual producer Jon Brion — she is closely guarded both sonically and lyrically, whilst simultaneously baring all in a stream of consciousness that is contradictory in in pointedness. The choice to lead with predominantly percussive and wholly acoustic production is further enhanced by the use of unconventional instrumentation, with "thighs," "pillow," and the mildly concerning "voice of pain" among those credited in the album's liner notes. As someone whose body was tabloid fodder early in her career, Apple's reclaiming of the physical frame to be used on her terms doesn't go unnoticed.

Opening song "Every Single Night" puts both the body and mind at center stage, the fragility of which is evidenced in the line, "That's where the pain comes in/ Like a second skeleton, trying to fit beneath the skin." The mental strife is skin deep and oozes through every orifice, to the point of rumination. "What'd I say to her? / Why'd I say to her? / What does she think of me?" — you'll be hard pressed to find anyone who hasn't gone to bed after a social interaction with the same thoughts, and despite the anxiety, it forms part of Apple's desire to "feel everything," as running away from exactly what she feels would diminish her own humanity. The aforementioned thighs in particular are a central part of "Daredevil," its hambone-esque cantering stopped in its tracks by Apple's demanding battle cry for attention: "Seek me out! Look at, look at, look at, look at me!" This very basic human need to be seen, in the midst of self-constructed chaos, is Apple at her most shameless. Many of us, myself included, are loath to admit, not only when we have been the architects of our own destruction, but also when we need saving from ourselves.

"Jonathan" similarly demands attention, in more ways than one, and is emblematic of the grim reality demonstrated throughout the album that romance unfortunately incompasses far more than swiping right. Written by Apple about her ex, You Were Never Really Here author Jonathan Ames, she remarks that she wrote it because "in the most affectionate way, he loves attention." With a narrative that takes place on New York's Coney Island, sonically reflected in its haunting wandering minor chords that sound like a fairground ride that is about to go off course, it effectively serves as the antithesis to "You're So Vain." Apple is equally critical and complimentary, treating her ex as a multifaceted human being and presenting both as equally fallible. Quelle horreur — accountability in a failed relationship! What will the patron saints of Tinder think?!

Fail not, she drops the better person-ism in "Regret," but is no less uninhibited with her feelings. Referring to another ex's frequent rebuttals as "hot piss," Apple is exhausted, yet still cutting, following this pillory with a guttural roar. The sparse "Valentine" however, stands out to me in regards to the opines on romance. Listening as someone who is a member of the Janis Ian Lonely Hearts Club, being those who have "never known" Valentines, Apple's comparison of herself to a "still life drawing of a peach" is particularly striking. Peaches are juicy, flavorful and with that little bit more vitality than a plum, but despite being ripe for picking, this one is "out of reach." Not for lack of trying, but rather to avoid being consumed. Why exist for those who will swallow you whole as opposed to those who will savor you for all you're worth?

The intensity in which I have increasingly felt seen with every listen of The Idler Wheel… isn't unique. Many of a generation even younger than me have discovered the album since its release and are similarly captivated. Fiona Apple's music is slowly creeping into the 'Gen Z sad girl' genre, a pejorative that would be offensive in its misogyny if it wasn't so boring. Some have bemoaned the 'TikTokification' of music, eager to gatekeep artists who are multiple Grammy Award winners and currently have several million monthly Spotify streams. It's almost inevitable at this point, so I say, if the kids want to be bombarded with a dose of stark realism to a timpani beat, let them! They'll be all the better for it.