- Warner

- 2002

Even at their goofiest, the Flaming Lips were so goddamned sad. The enduring memory of the band at their peak of visibility centers on their absurd, colorful live show: Wayne Coyne in a suit befitting a traveling salesman or a televangelist, surrounded by dancing furries and streams of confetti, dousing himself in blood and rolling across a field full of festival-goers in a giant plastic bubble. They seemed like living cartoons, and never more so than when singing what could be the plot of an anime. Yet more often than not, the Lips' psychedelic circus was a way for Coyne to reckon with intensely heavy real-life experiences. It was true on 1999's game-changing masterpiece The Soft Bulletin — on which Coyne memorably asked, "Will the fight for our sanity be the fight for our lives?" — and it remained true on that album's hit follow-up.

Yoshimi Battles The Pink Robots, released 20 years ago this Saturday, found the fearless freaks Trojan-horse-ing a record of depressive downtempo pop experiments into the hipster mainstream via a novelty song about a Japanese warrior girl training to fight killer machines. Yoshimi was no concept album; if its songs cohered around a central conflict, it was the struggle for hope in the face of despair, not the war between the title character and her mechanical foes. Yoshimi didn't even really seem like an avatar for anything specific, and at least at first, she wasn't. As Coyne explained to Yahoo years later, the concept originated when Yoshimi P-We, one of the drummers for the esteemed conceptual psych/noise band Boredoms, lent her voice to the squelching, stomping, perennially descending instrumental that became "Yoshimi Battles The Pink Robots, Pt. 2.":

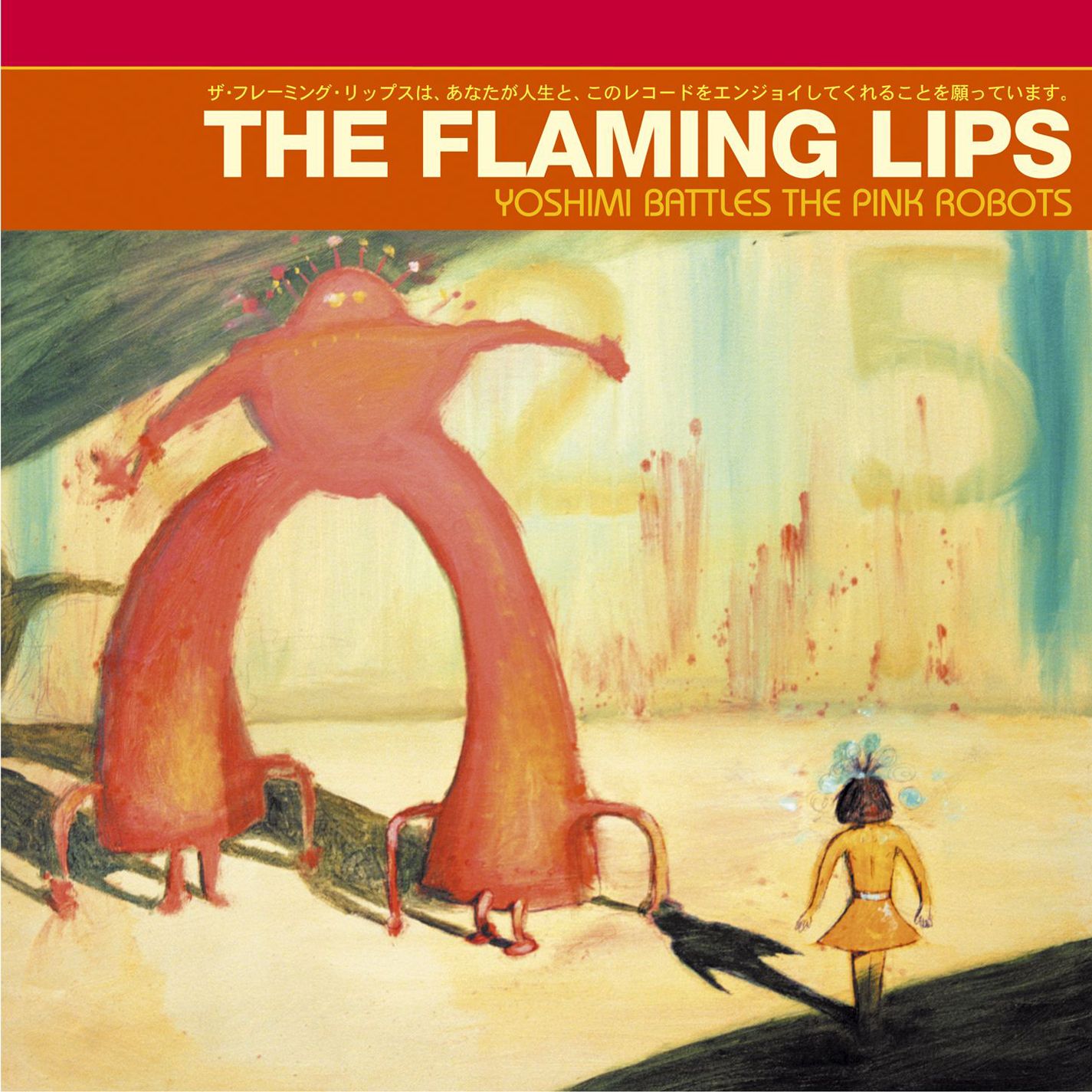

Initially it was just a track that has this woman, a real musician named Yoshimi P-We. We were sprinkling her singing and her playing and her screaming and her ad-libbing through different sections of the songs that we were starting to refine and arrange. "Yoshimi Battles The Pink Robots, Pt. 2" is an instrumental that has a lot of her screamings and these little karate chop sounds. We're putting that in an arrangement that sounds like some kind of machine. When Steve [Drozd] and I went back into the control room, [producer] Dave Fridmann said, "That sounds like Yoshimi who’s screaming and doing all the karate chop sounds is either having sex or being killed by a giant robot." And then I said, "It would be a pink robot." It became "Yoshimi Battles The Pink Robots, Pt. 1." And then we made other songs that related to that theme, and I painted the album cover.

The oil painting that graces the album presents a David-and-Goliath scene; the young Yoshimi is shown from behind staring down a long-legged pink giant. "Yoshimi Battles The Pink Robots, Pt. 1," an earnestly goofy campfire singalong that functions as a fight song for Yoshimi, further frames the album in these terms. To an extent, so do the two songs that bracket it on the album. But it's a stretch to connect most of these tracks to that storyline — which is a good thing because two decades later it feels pretty inane to howl along with lyrics like "Oh Yoshimi, they don't believe me/ But you won't let those robots eat me." The song is attention-grabbing and brilliant in its simplicity, little more than some acoustic chords and a catchy, whimsical hook. From a listener perspective, it's a good reminder not to take yourself too seriously. But a whole album of songs like that would be cloying to the extreme. Fortunately the Lips had a different kind of trip in mind.

Just as the braintrust of Coyne, Drozd, Fridmann, Michael Ivins, and Scott Booker came up with their own distinct musical language on The Soft Bulletin — a hyperreal orchestral psych-pop that pulled from across music history and the outer reaches of the imagination — they once again concocted a unique aesthetic for Yoshimi. Drozd's bashed-out drumming was largely replaced by programmed beats, a self-imposed restriction of superpowers comparable to Radiohead's sparing deployment of guitars on Kid A. Ivins' darting melodic basslines came to the forefront, essentially functioning as the hook on tracks like "Ego Tripping At The Gates Of Hell" and "One More Robot / Sympathy 3000-21." Acoustic guitars and loosely zany keyboard tones figured in prominently, as did samples and sound effects, with interstitial returns to Soft Bulletin drama sometimes gluing songs together at the seams.

In that Yahoo interview, Coyne talked about taking inspiration from the mainstream pop, rap, and R&B of the moment, comparing their own work with innovators like Timbaland — a commonplace trope now, but a radical departure for an alternative rock band at the time, even on the heels of the so-called "electronica" boom.It was certainly a twist within the Flaming Lips catalog, which had always been melodious but had never delved so deep into the digital realm. "To us, we were experimenting with pop music," he explained. "We would listen to things like Nelly Furtado and Madonna and we would say, 'Why don't we try to do that to our music?' Like, 'Wouldn't it be funny if?' Not thinking we're making commercial-sounding music — we're thinking, 'We're gonna put these big beats and these funny, quirky sounds to our simple little songs about robots. And wouldn't that be interesting?' And it was!"

Within Yoshimi’s world of vibes and textures, Coyne mewls about the pain of heartbreak, the cost of forgiveness, the search for meaning, and the threat of life passing you by. He often sounds weary and depressed, and even when he takes an inspirational turn there's a mournful glint in his voice. On "Are You A Hypnotist??" he laments the loss of intimacy with a former flame: "I thought I recognized your face/ Amongst all of those strangers/ But I am the stranger now/ Amongst all of the recognized." On "Ego Tripping At The Gates Of Hell," he sings about a similarly painful epiphany: "I was waiting on a moment/ But the moment never came/ All the billion other moments/ Were just slipping all away." There are songs about coming to terms with your fate ("In The Morning Of The Magicians") and learning to see the good in the world ("It's Summertime"). In the end, on the album's slowest song, Coyne declares, "All we have is now."

This kind of electro-organic existential reflection comprises the bulk of the album. Most of those chilled-out, heavy-hearted tracks hold up pretty well, and they represent a fascinating chapter in the Flaming Lips' history. The closing instrumental "Approaching Pavonis Mons By Balloon (Utopia Planitia)" won a Grammy against competition like Joe Satriani and Slash. You can make a case that Yoshimi laid groundwork for the extremely vibey indie subgenres that followed in the late 2000s and 2010s, from chillwave to "RIYL Tame Impala." But the album is not a top-to-bottom classic like The Soft Bulletin, and even at the height of my Lips fandom I made liberal use of the skip button. Usually I was skipping to one of three tentpole singles: the lovably goofy "Yoshimi Battles The Pink Robots Pt. 1" or one of a pair of anthems that translated all that ache into soaring transcendence.

The best-loved song on Yoshimi is almost certainly "Do You Realize??," the secular hymn that emerges late in the game to snap the album out of its funk. "Do You Realize??" is not the last song on Yoshimi, but it serves as the album's grand finale and has closed many a Flaming Lips concert. Musically, it blurs together the Soft Bulletin and Yoshimi aesthetics, melding acoustic strums, synthetic burbles, chiming bells, pogo-ing lead guitar, an arching string section, and more into a symphonic psych-folk power ballad extraordinaire. Within the bittersweet swirl, Coyne strikes just the right balance of tenderness ("Do you realize that you have the most beautiful face?"), painful realism ("Do you realize that everyone you know someday will die?"), and pseudo-profundity ("The sun doesn't go down/ It's just an illusion caused by the world spinning 'round"). The result is emotionally charged yet close enough to a blank slate to project whatever intense feelings you're feeling at the moment. In a giant crowd or within the privacy of your headphones, it tends to successfully tug at the heartstrings.

Yet for me, Yoshimi is never more sublime than on "Fight Test," its masterful opening track. Yes, I'm aware that the melody was lifted from Cat Stevens' "Father And Son," for which Coyne apologized in a 2003 Guardian interview. But as Coyne pointed out in the same breath, "There is obviously a fine line between being inspired and stealing," and "Fight Test" is nothing if not inspired. The song stands tall among the many, many examples of thievery in pop music history. It's so beautiful. The "Fight Test" melody is great, obviously, but so is the graceful, glimmering array of sounds the band assembled around it, an interstellar burst that has always struck me as a surreal cousin to Radiohead's "Airbag." And though the track would be spellbinding strictly as a collection of recorded sounds, it's elevated to the stratosphere by some of the most painfully straightforward lyrics Coyne ever wrote.

Rather than any kind of silly robot situation, "Fight Test" is about real shit: specifically, realizing too late that you should have done something rather than let your lover slip away into someone else's arms. There's some loopy stuff about sunbeams on the chorus, but the wonderment works like a charm in the context of the verses, each one more devastating than the next, leading to the dagger: "Cause I'm a man, not a boy/ And there are things you can't avoid/ You have to face them when you're not prepared to face them/ If I could, I would/ But you're with him now, it'd do no good/ I should have fought him, but instead I let him/ I let him take you." I don't know whether those lyrics are based on a true story, but within the song's gorgeous sweep, they never fail to make me verklempt. Even at their saddest, the Flaming Lips were so goddamned beautiful.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!