Pretty lovely lyrics, right? Maybe a bit self-conscious considering the kid singing them is about to wail his head off in the next verse. But I think we can agree that the white-hot angst of 20-year-olds allows them certain artistic liberties.

That kid, now a slightly less angsty 32-year-old folk musician who no longer screams, was once a part of William Bonney, an Indiana group that broke up in 2013. Bonney are an incredibly prominent name if A. you belong to the sliver of the population with a tolerance for so-called screamo music and B. you happened to be paying attention during the style's initial revival at the turn of the last decade. That is to say, not an otherwise prominent name.

But, hey, fuck a Spotify monthly listener count! It wasn't so long ago that I considered getting those lyrics — which open the group's sole EP — as my first tattoo. (Wiser heads quickly cautioned me: Hey, bozo brain, do not get a lifelong tattoo containing the words "you're a kid.") Bonney's words felt summative, encapsulating a form of punk expression that may very well have saved my life. Here was the promise of earnest, healing passion that draws misfits like me to screamo.

Apologies to the elder millennials who snuck out to VFW hall gigs or slaved away at the county mosquito control unit to mail out for Level Plane seven inches. Screamo came to me by digital happenstance, the same way all the most romantically obscure subgenres of past generations tend to materialize to people born after 1998. All I can say is listen to Alexisonfire on YouTube enough and REAL EMO VIOLENCE playlists will appear like petrichor after rainfall (only that first album, though — the one with that sickass schoolgirl knife fight on the cover).

Though I still found catharsis in the occasional metalcore stomp around our block, screamo's jarring tempo shifts and wild, razor sharp guitars proved a far more topographical match for the peaks and valleys of my mind. The genre became something I could depend on. A safe place where my goofy teenage misery would always be mirrored exactly, even if — heck, maybe because — the specific words were largely indecipherable. Here were kids as anonymous as me, with lungs just as full of broken emotion. It was enough to trust that their feeling was genuine. And in a scene with no stars, no glory, no reason to get involved except the bleeding heart community of it all, trusting was easy.

But now? Now I'm well aware that William and I were both overthinking this screamo shit (please note that none of the four people in William Bonney were actually named William Bonney). When a Nuvolascura gig fills a 150-cap venue, the psychic bond unifying that room is more likely than not pretty banal. After all, what are the odds that each of us — you, me, the girl up there soaking the microphone in phlegm, the dude behind her about to unleash fury with his fuzz pedal — feel things deeper than everyone else in the heavy music world? A blown-out human voice, its capacities maxed by savage anguish, is gonna get the blood pumping no matter what genre name you try to silo the meatheads out with. There will always be those for whom screamo is nothing more than an excuse to "SEE YOU IN THE PIT."

The latest round of screamo reunions can't be discussed without addressing the allegations against Jamie Behar — and Behar's response. Behar is arguably the sonic architect of modern screamo. More than City Of Caterpillar (pictured above) and Jeromes Dream — the other two foundational bands that have reunited in the last few years — you can draw the clearest line to today if you start with Saetia, the group Behar and some fellow NYU undergrads formed in February 1997. Not only are most of their winding, chaotic compositions attributable to Behar, his jagged lead lines were decisive in moving the genre past its hardcore punk origins towards a more intuitive, if no less muscular, emotionality. Upon his exit from Saetia last month, he wrote that the band is debatably "my greatest artistic legacy," which was about the only part of the statement that rang true.

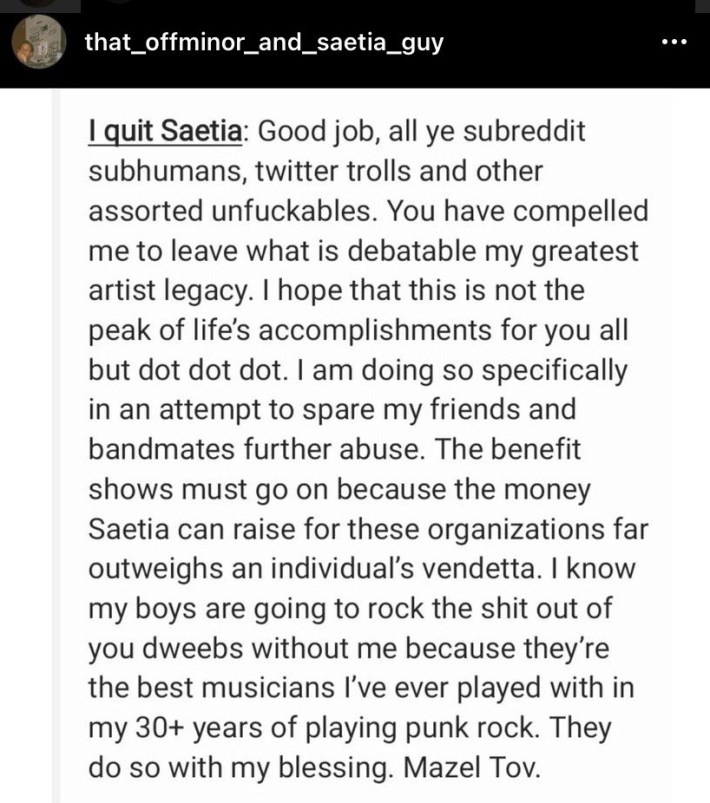

Behar left Saetia amidst a cloud of controversy. In early August, Becca Cadalzo, vocalist for the Boston hardcore band Cerce, accused Behar, her former romantic partner, of a lengthy pattern of emotional abuse. The other members of Saetia swiftly extricated him from their upcoming reunion shows. Behar, who had initially posted an apology, followed his dismissal with a combative, defensive statement on his personal account, in which he asserted that he hadn't been forced out of the band, he'd quit. Both Cadalzo and Behar have since deleted their accounts, but as documented in screenshots and on the No Plus Ones podcast, Behar's message began, "I quit Saetia. Good job all ye subreddit subhumans, Twitter trolls, and other assorted unfuckables."

Behar's absence makes it easier to compartmentalize and buy a ticket to the Saetia gigs if you wish. But there's also no need to see this particular band to experience music like theirs anymore. Jazzy guitar phrasings or no, plenty of bands sound like Saetia — they're the genre’s Model T. After I read Behar’s "you can’t fire me, I quit" Instagram temper tantrum, his music ceased to have any function for me. If screamo at its best can be reduced to one band’s self-laceration in service of a broader community’s emotional release, the statement revealed Behar as basically the least screamo dude of all time. It’s almost impressive. Behar, a 46-year-old man, concedes not one inch of personal failing, ruthlessly flouts his accuser’s experience, and any time he’s not threatening to beat up former fans he’s threatening to sue them. How did the guy who helped pioneer the only music that’s consistently as aggressive as it is vulnerable totally forget the second half of that equation? Talk about lungs full of hot air. It made me wonder; was the wind power that generated Jeromes Dream and City Of Caterpillar similarly blusterous?

It can be easy to forget, but therapeutic outreach wasn't really a part of the 1990s screamo blueprint. Instead, the bands who started building from it in the early 2010s were really the first ones to explicitly offer themselves as candidates for melancholy lyric tattooing. They made concept albums about dying loved ones and gave themselves names like Unable To Fully Embrace This Happiness. Some of them seem to have straight up become emo bands.

By contrast, the so-called skramz groups (a term I use reluctantly, if only because several musicians from those bands have now told me they hate it more than they already hate "screamo") were far more emotionally remote, even unknowable outfits. There's a real standoffishness to, say, Pageninetynine issuing all their releases as untitled "Documents" or the smartass track title humor that defuses each lacerating Orchid song ("No, We Don't Have Any T-Shirts" is a favorite).

For a while, the most immediate extramusical indicator of how passionately the skramz flame once burnt was how utterly extinguished it was. Each band — without exception — broke up prematurely,leaving behind only a stark single-disc discography compilation as a headstone. Here were bands as deep in the ground as a goofy teenager is sometimes gonna want to be — their pain so awesomely authentic they had willed themselves right out of existence. "Reversal of Man is Dead, 1995-2000" — that's literally one beloved Florida band's entire Spotify bio.

"If you told me back then that people would one day find emotional solace through our music I'd have gawked at you," Erik Ratensperger explains to me. He's the 43-year-old drummer for Jeromes Dream, the disconcertingly savage New York powerhouse that's a heck of a lot harder to rip off than Saetia. "Our passion wasn't driven by someone else's theoretical catharsis. It was three fucked-up dudes, alienated from their surroundings — channeling that into the most authentic possible expression to find security for ourselves."

These weren't sensitive diarists, but real punk kids, alienated from society and raised on grind, powerviolence, and youth crew. Far from striving to fall off the face of the earth, they wrote letters to scene idols and formed bands as a shortcut to joining that community. Even so, their alienation from hardcore's more mosh-minded trends directly resulted in the headier, more introspective style they developed. When refusal to compromise resulted in soul-draining performances at emptied out DIY spaces, they found themselves alienated from broader hardcore society as well. If death of morale didn't cause their break up, the way it did for California's Portraits Of Past, the reasons were even more mundane. Sometimes, as for Ratensperger, college was starting. In the case of Will Killingsworth, one-time guitarist for happily disbanded Amherst legends Orchid, college was ending. Pack it in. Find a real life.

"When it was new, in the context of hardcore, this music used to be inherently aggressive. Bands wanted to play as abrasively as possible but without any of the usual testosterone behind it, " recalls Killingsworth, today an engineer who has spent two decades recording, mixing, and mastering music by his endless screamo descendants. "But screamo isn't in the shadow of hardcore anymore. It's an insular, well supported scene; it's not gonna be angry music by default."

As fully grown adults returning to screamo, these bands are entering a scene that provides none of the emotional resources that once drove their whole existence. Today, the form is more like the shared, well-understood language of a legitimate community — a means to a more diverse array of expression, with artists bringing their passion to screamo rather than finding passion through it. Quite the happy development for a genre once almost entirely driven by the angst of middle class white men.

"It's really been the last seven years or so I started noticing it, this incredible uptick in bands based around trauma, identity, and social politics," explains Dave Norman, the mind behind Zegema Beach Records, the most consistently excellent and prolific screamo label going. "Very intentionally being, 'this genre is my one vessel to express myself and help others like me.'"

"Discovering screamo through YouTube holes, I was like, oh, it's like a diary." explains Blue Luno-Solaz, 23-year-old vocalist for Foxtails, the Connecticut band opening for City Of Caterpillar in the fall and creator of 2022's most acclaimed screamo album (with, you heard it here first, an EP soon to follow). "Screamo can directly document my experiences with violence and abuse, these emotions too extreme for other music."

Luno-Solaz has also had a bit of experience with the protective insularity of the modern screamo and emo scenes — the way expression stands revealed as fraudulent when the character behind it gets called into question. Though quickly disproven, abuse allegations of their own got Foxtails removed from a Touché Amoré tour this past winter. Even getting past Behar-inspired questions of ethics, Luno-Solaz and I discuss whether a reheated skramz angst can survive in a scene dominated by present-tense emotionality. "I pay respect to the old screamo bands. They opened the door," they explain. "But do we want to see a bunch of old dudes getting up on the stage, still screaming about how they don't know how to manage their teenage emotions? How could they possibly mean it?"

"It's not a genre that offers a lot to compensate if the passion isn't coming from a real place," cautions Norman. "Screamo is only for the fully invested."

Billy Werner, lead vocalist of Saetia, clearly at one time thought something similar. On a 2017 episode of the aforementioned No Plus Ones podcast (shout out Dave Anthony and Dan Ozzi), Werner explained why Saetia would (welp) never get back together. Besides all the usual self-aggrandizing talk of not "exploiting" a "sacred thing," Werner said the idea of emotionally accessing lyrics he wrote in high school "creeps him out" and that he "definitely could not do that with my voice anyway." More significantly, he wants to "allow DIY to thrive for the people it matters most to now," that is to say, not "a 40-year-old straight white dude reliving his glory."

"That's kind of why I don't want to get Orchid back together. Well said Billy," laughs Killingsworth when I read him Werner's quote. "I saw Saetia in a record store playing for 15 people. Put that in a metal club 20 years later, it's not gonna produce the same experience — for band and audience. It's weird to say ‘we are once again this band,' and exclusively do things the band never did."

So skramz past can't be resurrected, but is there still a chance for a meaningful memorial? If bands lean into their age and experience, can they leverage their distance from teenage passion into mature reflection? That's the intentionality with which arguably the very first skramz band, Portraits Of Past, approached the very first skramz reunion way back in 2008.

As vocalist Rob Pettersen tells me, POP received almost nothing but disinterest during their brief existence, finally breaking up in 1995 after a "tough tour with a small turnout." At one low point they were straight up asked by Ebullition Records why they weren't more like Bleed, the forgotten band on the other side of their 1994 split. Reinvestigating the hardcore scene in the mid 2000s, the band were shocked to discover that not only were they the remembered ones, there were entire scores of bands created in their image.

Though the cynical message-board set grumbled that the band were chasing the glory they never got, those who attended POP's brief run of "idealized 1995" gigs found a far more communal affair — bittersweet wish fulfillment for anyone who owed a debt to these pioneers. The venues they opted for were legendary punk spaces like 924 Gilman, research was done to find openers who had carried on their legacy, and the band themselves made a generous effort to honor the fans who had ensured they even had one. In addition to all the material crowds chanted for, forward thinking new material was written with lyrics that Pettersen says "reflected on [his] memories in hardcore and how those experiences had contributed to [his] maturation."

"It was not about us as people," recalled guitarist Rex Shelverton in a 2020 interview with Ratensperger "because nobody knew about us." Indeed, though fans rushed on stage to hug POP when they performed, the band recall being struck by how few stuck around to mill about post show. Vessels for expression they remained, and the band once again disbanded following the release of one EP in 2009.

Despite setting such a heartwarming precedent for skramz revivalism, I'm not confident the POP reunion can be replicated. They got back together at a time well before the screamo revival had revealed the genre's longevity. The gigs were saluting a then-recessive form as much as the band who had originated it. In 2022, what can a skramz revival gig at a posh venue offer us that a no-name band in a YMCA basement down the street can't give us at a fourth of the price?

Kevin Longendyke, bassist and vocalist for Richmond's City Of Caterpillar, first started playing reunion gigs in 2017. The spiraling, post-rock-inspired epics that comprise the band's 2002 debut are about as abstract as screamo gets. I was eager to learn what youthful alchemy had inspired their composition and whether their 20-years-in-the-making follow up, Mystic Sisters (out this Friday via Relapse), was intended to maintain it. The press notes suggested the band wanted to have it both ways. When vocalist Brandon Evans writes the band wanted to "make it show that 20 years have passed, but also make it seem like this record could've come out right after the other one," he sounds like he's preparing us for a low energy retread.

At first, my Zoom with Longendyke seemed to suggest a band with no driving passion. A gruff, unsmiling punk guy wearing sunglasses in the back of a car, he blanked on interactions with fans, professed little knowledge of the modern screamo scene, and described CoC's hallowed songwriting process as just "guys bringing riffs together." Finally, I straight up asked it: What drives them to make such anguished-sounding music and not, like, fucking '60s garage rock. "It's just how we are and it's a natural thing for us," Longendyke shrugs. Then he tells me he does in fact also play in a band that does '60s style garage rock.

It takes me a while, but I do eventually *get it*. Listening to the outstanding Mystic Sisters helps; if anything, that shit goes even harder than debut. But more importantly, I finally get it through my thick skull that CoC aren't doing this for anyone but themselves. Not in the "chasing glory" sense, but in the sense that they genuinely *love* one another and adulthood has taught them how easily loved ones can slip away. "The new music is written from the same desire as the old," Evans tells me. "To simply create and experiment within a social group."

This is a band of pre-existing friends that formed without any material out of desperation to tour with their pals in Planes Mistaken For Stars. This is a band that has never been able to answer the question "Why did you break up?" This is a band that once referred to their reunion tours as being like "family vacations for friends who don't live anywhere near one another." And if you know how meaningful, difficult, and precious it is for these dudes to get together, the fact that Mystic Sisters was galvanized by the 2021 death of PMFS frontman Gared O'Donnell automatically makes it one of the most authentic screamo albums of all time. A howl to bring a community together.

So sure, grouse that CoC are making basically the same music they did as youths. But don't forget they're doing it all again so they can keep doing it forever. "We would never want to mess with something that lets us play music and make art together as friends," Evans says. Mystic Sisters forever.

Jeromes Dream, by contrast, are determined to never stop messing their thing up. From the beginning, Ratensperger tells me the band's initial style rendered them the skramz scene's "odd men out." If listeners weren't thrown off center by the discordant riffs attempting to stick a landing onto Ratensperger's manically shuffling drum patterns, Jeff Smith's piercing wail almost certainly did the trick. What few fans glommed onto 2000's Seeing Means More Than Safety were quickly lost with the next year's Presents. (Important lesson: If the world's most apocalyptically passionate band tell you they're about to release their "fuck you" album, don't be surprised when it tumbles out as cryptic mathcore with no obvious emotional application.) After the college-bound Ratensperger surprised his bandmates by disbanding JD on stage, the group finally checked off the last constituents that had previously remained un-alienated: one another.

"Absolute emotional honesty, that's what guides us," explains Ratensperger of his band's trajectory. "Onto the next thing, always. I can respect an approach like City Of Caterpillar, but that's not us. In true JD fashion, we don't give a fuck."

Well, maybe they give a *little* fuck. Like their peers, JD finally found an internet following as a dead band. Not only did the discovery revitalize the band's relationships, it affirmed how "valuable it was for friends to share a legitimate expressive outlet that generates such good will." It's a testament to this pioneering band that their reunion instantly blew it.

"I was like, oh cool, they're not gonna tour first, they're not gonna use a label, they're gonna record a new album and jumpstart this band through Kickstarter crowdfunding," Dave Norman recalls. "And then you go on the internet, and people in the community just lost their fucking mind."

Even mentioning JD's 2019 album LP will raise the hairs on any skramz fan's neck. Initial accusations of "cash grab" were bad enough beforehand; things exploded when skeptical fans actually listened to the record — 33 minutes of feedback-free shufflepunk without so much as a second of screaming. But to hear the band tell it, the album is as much of an authentic document as anything they've ever recorded. The jammed-out instrumentals were expressive of material written remotely and recorded by a band struggling to rebuild their dynamic. Smith's hesitant, mild shout vocals come from a place of frustration — a middle-aged man's failure to "reconnect with his voice." Does that make the album good? Well, no. But it does make it screamo, kinda, in that vague, ethical sense. You are certainly hearing real emotions on record. Honoring them turned out to be necessary for what happened next.

In short: Smith started screaming again. Nobody can explain it rationally. When JD began their first reunion tour, the emotion of once again being on the road together simply pushed them back into the pocket, resulting in shows as rapturously received as any modern screamo band. While the band remain proud of LP as an honest document of "reunion confusion," Ratensperger promises slightly more rambunctious feelings have been chronicled on the as-yet-unannounced new record JD spun out of their revitalized head space.

"It's the record I wish we could have made in 2019, though I understand we had to earn it. It doesn't sound like Seeing Means More Than Safety. It's, how do I put this, heavier." Ratensperger says, an admission sure to startle anyone who has survived the onslaught of that album. "Gosh, I hope we're doing this through our 60s."

Ratensperger talks to me for almost two hours, to the point where I kind of have to hang up on one of my all-time musical heroes. Yet when I hear him analyze the ways he's adapting his youthful mode of expression to the twists and turns of adult life, it's not some punk blowhard clattering on for relevance. Instead, I feel that old faith I used to back when JD's untimely death was all that was screaming for them. It's a lot stronger now. No, these lungs aren't full of broken emotion, but something different. A deeper, more considered intake of air — the kind of cavernous gulp you make when you're planning to stick around burning oxygen for a while.

"Hardcore used to be our whole world. But even more now that we have lives, partners, jobs, kids, we're committed to expressive truth," Ratensperger says. "How could you ever ever pump bullshit from the one facet of life that's wholly your own? It would wreck us."

So. Are these bands shepherding us into a world where emotionally authentic screamo music is as sure a bet from the old as it is from the young? Can we expect to see brand new bands with a mean age of 45 sprouting up on Zegema Beach and hitting the stage of New Friends Fest? Am I ready to suspend disbelief that a dude with a mortgage feels the full brunt of life's confusing passions as vividly as a 21-year-old? Well… I'll let Blue from Foxtails answer that question.

"Gen Z — we're fucked, like, we're totally fucked," Blue says. "You can trust, no matter what, we definitely have shit to scream about."