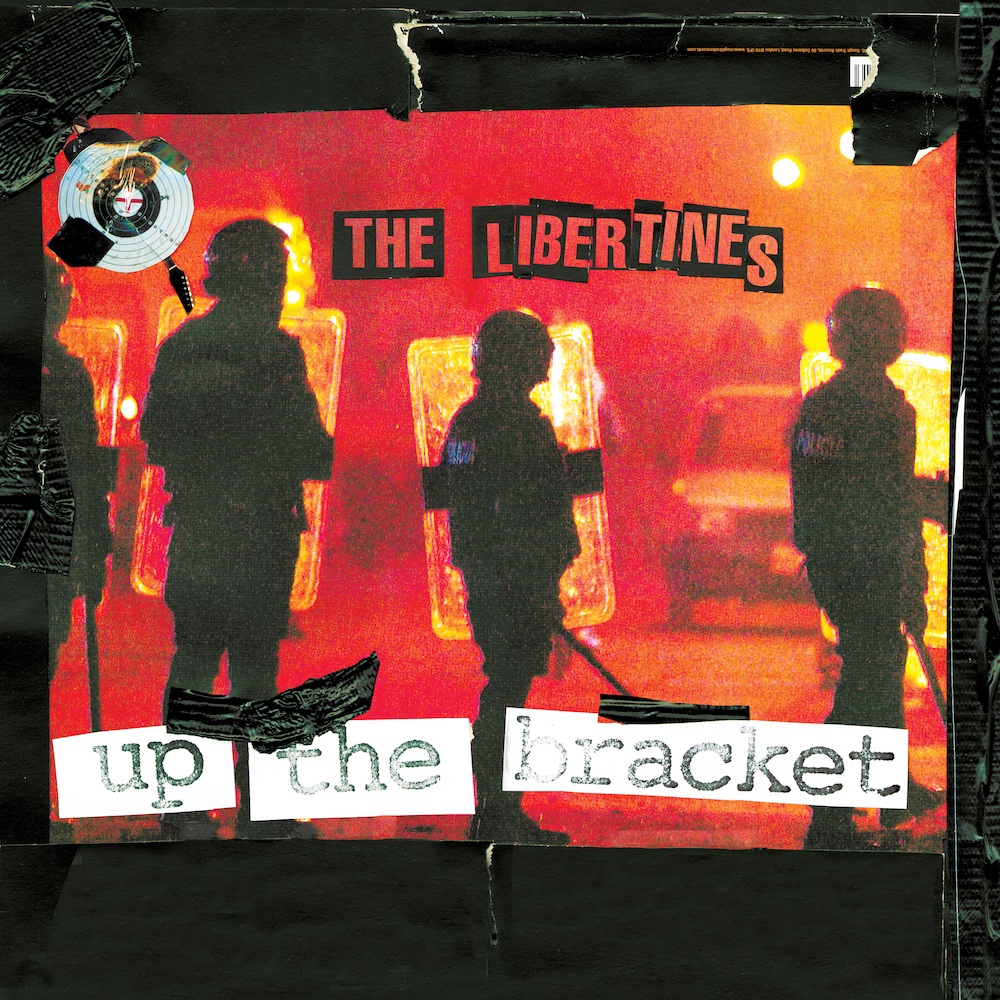

- Rough Trade

- 2002

If you play the Libertines' scene-rejuvenating debut Up The Bracket all the way through on Spotify, I’ll give you one guess as to what auto-plays next. Yes, it is the Strokes. In October 2002, when Up The Bracket first came out via Rough Trade, the Libertines were being hardcore marketed as the UK’s Strokes. Big-city roots? Check. Ratty T-shirts? Check. Rock revivalist ideations? Check. ...Drugs? Don't include in the press release, but yes, also check.

Two decades later, it's still easy to see why the industry wanted those London rapscallions to mirror Julian Casablancas & Co.'s rock savior shtick. In the early 2000s, both bands, in their own way(s), helped generate a renewed interest in garage rock and a downtown-cool aesthetic, when, for the last five or so years, popular music was mostly giving boy bands and, depending on your side of the Atlantic, either butt rock or Radiohead clones. The UK hadn't had rambunctious, tabloid-friendly guitar bands (and the attendant rock-star stereotypes and infighting) since the '90s Britpop churn sputtered and gave way to the Spice Girls. While the Strokes-Libertines parallels are so easy to make that even an algorithm will immediately group them together, the Libertines were not coattail riders – they were very much their own thing. For better or worse (and there was a whole lot of drug-addicted worse), the Libertines — bolstered by the perennial love-hate relationship between Pete Doherty and Carl Barât — helped set a raucous, belligerent, I-love-mess precedent for a whole new wave of UK rock pioneers.

Before they shared guitar and vocal duties, the Libertines’ Doherty and Barât shared a flat with Doherty's older sister Amy-Jo. Doherty and Barât were college students then, with Barât studying drama at Brunel University and Doherty studying English lit at Queen Mary College (where yours truly did a semester abroad!). Eventually, both Barât and Doherty, having bonded over shared love of songwriting, dropped out of their respective courses and moved into another flat on Camden Road in North London, a space they lovingly referred to as "The Albion Rooms." (I picture a furniture-less Young Ones-type scenario when I think of Doherty and Barât rooming together.)

Along with their neighbor "Scarborough Steve" Bedlow, Barât and Doherty called themselves the Strand, and, eventually, the Libertines, named for Marquis de Sade's unfinished novel Lusts Of The Libertines, which, per Wikipedia, is about four men who go to extreme lengths to achieve "ultimate sexual gratification." Has there ever been a more fitting band name? (We’ll expand on that thought a bit further down.)

In the summer of 1997, Scarborough Steve introduced Doherty and Barât to students John Hassall and future Razorlight founder Johnny Borrell, who soon rounded out the Libertines’ lineup. Around this time, the band's lineup becomes exceedingly difficult to pin down — Steve had initially been the band’s singer, but because he was absent during an early demo-recording session, Barât and Doherty began sharing vocals, setting the stage for Up The Bracket’s dizzy call-and-response cadence. Also around this time, the Libertines played with a 54-year-old jazz musician named Paul DuFour, who filled in on drums, plus a cellist named Vicky Chapman. "We were like the Bootleg Beatles with a 70-year-old drummer and a fucking weird cellist. [DuFour] was looking for wedding gigs. We'd play god knows where, old people's homes. We were going to play 'Hey you, get off of my cloud' to the old folks," Doherty said in Pete Welsh's 2009 book Kids In The Riot: High And Low With The Libertines.

After a couple of years gigging wherever possible (basements, flats, kebab shops), the Libertines got their first-ever live review in NME, and it's a rave. The writer of that review, Roger Morton, at one point offered to be the band's manager, but the job eventually went to music lawyer Banny Poostchi, who helped the Libertines compile an eight-song demos EP called the Legs XI sessions. Few of those demos would show up as studio recordings on Up The Bracket, but a couple, like "Music When The Lights Go Out" and "France," did make it onto their 2004 self-titled second album.

Unsurprisingly, Poostchi quit her management role after struggling to get the famously ungovernable Doherty to play the right gigs to the right industry people. Once the Strokes exploded overseas, however, Poostchi began working on a UK publishing deal for the NYC band and wanted the same success for Barât and Doherty. Just do what I say, she told them, and the Libertines will be signed to Rough Trade in a matter of months. Under Poostchi's oversight, the Libertines got a new drummer — Gary Powell from New Jersey — and Borrell came back to play bass.

Despite Doherty's devil-may-care attitude, he did have high hopes for his band, and both he and Barât were frustrated at their overall lack of momentum. And now their potential rock 'n roll glory was being commandeered by a group of Americans? Nonsense. In this exceedingly thorough breakdown of the Libertines' history, Sarah Murphy outlines how Barât and Doherty channeled their simmering resentment into Up The Bracket and, as a direct result, got themselves signed to Rough Trade in December 2001.

Now, this is the part in the retrospective where I apologize if I got any part of the above timeline wrong, re: the Libertines’ revolving-door bass/drumming lineup. The lineup switcharoos are so sudden and so many, no one could legitimately be blamed for mixing up names and dates. At this point, all you really need to know is that the label-signing quartet would be: Doherty and Barât (guitars and vocals), John Hassall on bass, and Gary Powell on drums.

Released in October 2002, Up The Bracket actually sounded like its name, which is a term coined by Doherty’s favorite comedian, Tony Hancock. "Up The Bracket" means to get throat-punched. Though no one sounds strangled, Up The Bracket comprises 12 uproarious, vertigo-inducing, pub-crawling anthems stuffed with sing-along choruses and winding guitar-lines that somehow manage to sound both tight and chaotic all at the same time.

Up The Bracket draws considerable influence from British (and American!) rock history, taking cues from the Beatles and Kinks, the Smiths, Chuck Berry, arena-filling '90s Britpop, and, of course, the Clash , whose Mick Jones produced Up The Bracket. (Jones became a longtime Doherty collaborator, also producing The Libertines and Babyshambles’ 2005 debut Down In Albion.) At a brisk 30-ish minutes, Up The Bracket sounds like the work of a basement-punk band who also happen to be pirates and semi-educated college dropouts. The Libertines took all of these elements — plus a little exasperation at their own career roadblocks — and put out a completely boisterous blast of hits that manages to be everything all at once and sets the stage for an equally thrilling future.

While the Strokes paid clear homage to '60s garage rock and proto-punk, the Libertines practically made a rock-history mood board with Up The Bracket — except somewhere along the line, someone got drunk and turned the mood board into a Pepe Silvia conspiracy chart.

It's nearly impossible to choose a favorite Up The Bracket track — the winding and poetic "Time For Heroes" gets name-checked a lot by fans, particularly for its tongue-in-cheek lyric "There are fewer more distressing sights than that/ Of an Englishman in a baseball cap." The harmonizing penultimate track, "The Good Old Days," is a starry-eyed callback to the band's Albion days of yore, likening their old apartment to a ship ("The arcadian dream so fallen through/ But the Albion sails on course/ Let's man the decks and hoist the rigging"). My personal longtime favorite, "The Boy Looked At Johnny," plays out like a sitcom, with Doherty marble-mouthing a slew of comedic one-liners. (The "Johnny" in question is reportedly bassist John Hassall). Meanwhile, antsy riffer "Vertigo" sets the tone for the whole of Up The Bracket. The bawdy "Boys In The Band" stomps, speeds up, and slows down with agile guitar-work and absolutely rips on the bass. The slurring punk parade "Horror Show" is best remembered for Doherty exclaiming, "Oh no, please don’t show me!/ I'm a swine and you don’t wanna know me." (Pretty sure that lyric made its way into my AIM away messages once upon a time.)

Being an American, I cannot claim to know what it was like in London or the wider UK when Up The Bracket dropped in 2002. My most vivid memory of consuming this record was listening to it while sitting in high school study hall trying to disassociate from my peers. But I can speak to what it was like to be in London five years later. Skinny jeans were all the rage. Nights out consisted of knocking back bottles of wine and canned G&Ts before heading out to Tottenham Court Road, where a group of us would dance wildly to the Libertines — but mostly to indie acts that would draw heavy inspiration from them, such as the Arctic Monkeys, the Fratellis (ugh), Razorlight, and the Klaxons. It is thanks to the Libertines that these bands took over the NME and UK youth culture as a whole. Because the Libertines represented more than a band — they were an attitude.

What the Libertines gave us on Up The Bracket was pure lightning in a bottle, and ultimately not fit to last. Doherty's issues with crack and heroin addiction made it so that the band could barely hold themselves together on their best day. Doherty got himself kicked out of the band in 2003 and tried to burgle Barât's apartment before getting arrested and serving a couple of months in prison. He and Barât would reunite for 2004’s The Libertines, but that Up The Bracket-era magic had seemingly been eclipsed by Doherty’s persistent drug issues. Eventually, he leaned harder into promoting Babyshambles, with whom he released three albums.

In 2015, I interviewed Barât and Doherty around their 2015 reunion album, Anthems For Doomed Youth. I remember nothing about that record, but I will never forget how I panicked while listening to the transcript because I literally couldn’t understand a word Doherty was saying. He was a nice enough guy, though, and I will always feel impressed at his and Barât's ability to come back together after more than a decade of ups, downs, and debauched scenarios well beyond my comprehension. (Morrissey and Marr could never.) More importantly, the Libertines at their peak gave Britain a vital bit of post-Britpop pride, and provided a springboard for legions of future DIY creators to follow in their stead. The Strokes might be more immediately synonymous with the aughts rock revival, but the Libs will always be the ultimate boys in the band.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!