September 6, 2003

- STAYED AT #1:4 Weeks

In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

I wonder if Will Smith felt weird. In 2003, Smith wasn't the box-office colossus that he'd once been. The Independence Day and Men In Black days were over. With Robert Redford's inexplicable 2000 magical-golf-spirit travesty The Legend Of Baggar Vance, Smith had starred in a true mega-bomb. Smith got his first Oscar nomination for Michael Mann's 2001 biopic Ali, but that movie lost money, too. 2002's Men In Black II was a huge hit, but that was a gimme, and nobody liked it. A year later, Smith returned to the sequel well for the maximalist action spectacle Bad Boys II, which basically put Smith's movie-star career back on track. But what did Will Smith think of the Bad Boys II soundtrack? Was he bewildered?

Four years after Will Smith landed at #1 with "Wild Wild West," another Will Smith summer movie soundtrack featured another energetic, eager-to-please rap song that topped the Hot 100. This time, though, Smith had nothing to do with the song. Smith's run as a crossover-friendly pop-rap star was over; his 2002 album Born To Reign had flopped hard. The painfully awkward "Black Suits Comin' (Nod Ya Head)" peaked at #77, proving that a Will Smith soundtrack song could no longer sell a summer blockbuster. Smith had to accept that. But what did he think when Nelly, P. Diddy, and Murphy Lee didn't even rap about the plot of Bad Boys II? When they just rapped about butts instead? For the former Fresh Prince, that must've been a moment of culture shock.

When he announced the Bad Boys II soundtrack, executive producer P. Diddy said that he'd actually called Will Smith, as well as Jerry Bruckheimer, the film's producer. So Will Smith presumably had to sign off on the idea of Diddy putting together the soundtrack. As much as I like joking about Will Smith rapping the plots of movies, it was probably a no-brainer to get the former Puff Daddy involved. Sean Combs launched Bad Boy Records in 1993, and the first Bad Boys movie came out two years later. The film was named for the Inner Circle song that served as the Cops theme music, not for Puffy's record label, but there was some mystical convergence at work there. When Will Smith scored a pair of #1 hits in the late '90s, he was pretty much doing a family-friendly version of the flashy and sample-heavy pop-rap that Puffy had pioneered.

When Diddy heard that another Bad Boys movie was coming out, he was attempting to relaunch Bad Boy Records, to establish the label as a new version of the rap dynasty that it had once been. The timing was right. The Bad Boys II soundtrack is basically a Diddy album. He raps on three songs, co-produces a bunch of others, and plays hypeman on a few more. Some of the tracks showcase early-'00s Diddy proteges like Loon and Mario Winans. The whole compilation reflects Diddy's approach: brisk, funky, star-driven club-rap tracks that never aspire to be anything more than fun earworms. That's not exactly a recipe for artistic greatness, but it can make for a fun diversion. That's what the Bad Boys II soundtrack is. For that matter, that's also what the Bad Boys II movie is.

In many ways, P. Diddy and Bad Boys II auteur Michael Bay are a perfect match. Michael Bay probably doesn't sit around listening to club-rap; one of his big early breaks came when he directed Meat Loaf's delightfully preposterous "I'd Do Anything For Love (But I Won't Do That)" video. But Bay, like Diddy, has a sensationalistic signature style so singularly shallow that it can almost feel deep. Both artists are fully committed to explosive spectacle, and both have reaped a whole lot of commercial rewards. Plenty of critics consider both of them to be total pariahs, but they're both fun to have around.

Bad Boys II might be the purest example of Michael Bay's whole cinematic vision. It's utterly incomprehensible, way more concerned with whip-pan dazzle and dick-grabbing brinksmanship than any kind of logical plot movement. Diddy's Bad BoysII soundtrack probably isn't the purest example of his vision, but it helps give the movie a bit of a pulse, a sense of glamor. (The first Bad Boys also had a rap-heavy soundtrack, but it was a much more haphazard collection of tracks.) Diddy really worked his contact list for the Bad Boys II soundtrack. It's got Jay-Z and Beyoncé and 50 Cent and Justin Timberlake and Mary J. Blige. It's also got the last #1 hit of Diddy's career to date.

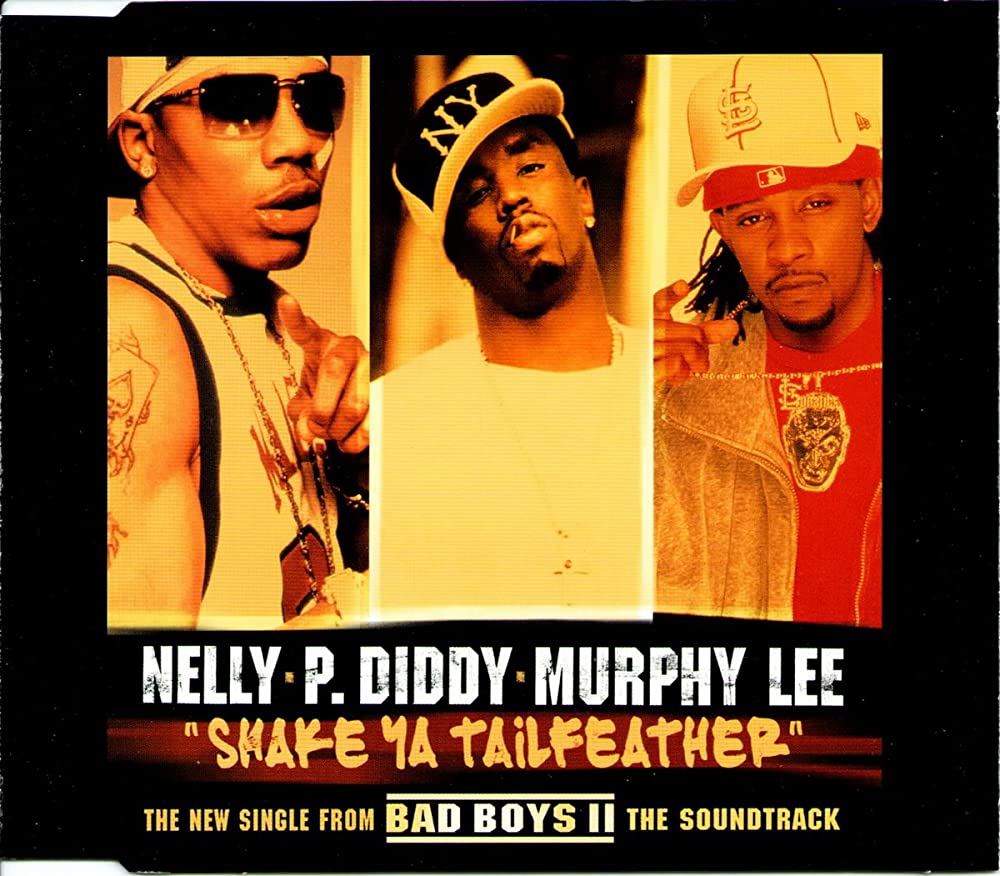

When Nelly teamed up with Diddy for "Shake Ya Tailfeather," he was cruising. The previous year, Nelly had released his sophomore album Nellyville, and it had gone sextuple platinum. "Hot In Herre" and "Dilemma" went back-to-back at #1, and they stood as that summer's two biggest hits. A year later, Nelly was in between album cycles, and a movie-soundtrack single was the perfect way to keep his name in rotation. It also gave him a chance to help launch Murphy Lee, the youngest member of Nelly's St. Lunatics crew.

Nelly never made stars of his fellow St. Lunatics, but it wasn't for lack of trying. In 2001, shortly after the release of Nelly's massively successful debut Country Grammar, the St. Lunatics released the group album Free City. It flopped, but Nelly kept featuring his friends on songs, including the infectious #3 posse cut "Air Force Ones." (That one is an 8.) The St. Lunatics kept showing up in Nelly videos, and they developed their own visual signatures. Hypeman Slo Down didn't even rap, but he had a nice little run as the guy with the Phantom Of The Opera mask in all those Nelly videos. Murphy Lee, a slight teenager with a chirpy voice and a left-of-center swagger, seemed to have some real star potential.

You couldn't blame Nelly for thinking he could turn his friends into stars. After Nelly's success, a whole lot of fake Nellys started showing up. Chingy, a squeaky and awkward young St. Louis pop-rapper who knew his way around a hook, signed to Ludacris' Disturbing Tha Peace label and made it to #2 with his debut single "Right Thurr" in 2003. (It's a 6.) More Nelly wannabes would follow. In 2004, J-Kwon, another St. Louis hopeful, reached #2 with the stomping, elemental club track "Tipsy." (It's a 9.) In 2006, Huey, yet another fizzy club-rapper from St. Louis, got to #6 with "Pop, Lock & Drop It." (That one is an 8. Huey was shot dead in 2020 at the age of 32.) In the '00s, anyone watching BET got pretty used to seeing videos open with establishing shots of the Gateway Arch. If everyone else was going to come out with fake Nellys, maybe Nelly figured he could introduce a fake Nelly of his own.

Murphy Lee wasn't really a fake Nelly. I always liked Murphy, who rapped with a ton of enthusiasm and who had a gift for random, unexpected punchlines. That energy was on full display on "Shake Ya Tailfeather." P. Diddy might've been the architect of the whole Bad Boys II soundtrack, but "Shake Ya Tailfeather" is very much a Nelly song, with Diddy mostly trying to stay out of the way. "Shake Ya Tailfeather" is an absolute trifle, but nobody ever needed to hear anything deep out of a Nelly track. Instead, Nelly was great at a very narrow type of thing -- honking simplistic beats, berserker singsong hooks, lyrics about girls dancing.

"Shake Ya Tailfeather" is such a simple song that it almost doesn't have a concept. It's just Nelly, Diddy, and Murphy Lee talking about how much they love watching girls shake asses. This was not a new concept. In its title, "Shake Ya Tailfeather" was practically a clone of the Five Du-Tones' "Shake A Tail Feather," a wild and energetic dance-craze jam that peaked at #28 in 1963. Seventeen years later, Ray Charles sang "Shake A Tail Feather" in The Blues Brothers. "Shake Ya Tailfeather" doesn't sample or interpolate "Shake A Tail Feather," but the spirit is the same.

"Shake Ya Tailfeather" does interpolate something a little more unfortunate: the War Chant, the crowd call famously associated with the Florida State Seminoles. That whole "whaaa-ohhhh" thing is racist as fuck, just like its cousin, the Atlanta Braves Tomahawk Chop. People weren't really thinking about the origins of those chants in 2003, but if you're still Tomahawk Chopping today, you're a dick. I'm giving Nelly and friends a pass on this one, but maybe the War Chant is the reason that I never hear "Shake Ya Tailfeather" anymore. Or maybe "Shake Ya Tailfeather" was just built to be disposable. That doesn't mean it's bad, though.

The "Shake Ya Tailfeather" video opens with the three rappers talking about which parts of women's bodies they like best -- pretty tone-deaf, especially considering that people were already mad at Nelly for swiping a credit card between a woman's asscheeks in his porny "Tip Drill" video. (Nelly would later be accused of rape and sexual abuse, and we'll get to all that in a future column.) On "Shake Ya Tailfeather" itself, though, Nelly never comes off as an asshole. Instead, he delivers all his pickup lines with yelping singsong urgency, and those pickup lines take some strange turns: "Is that your ass, or your mama half reindeer?/ I can't explain it, but damn sure glad you came here." There's charm in his weirdness.

Nelly co-produced the "Shake Ya Tailfeather" beat with frequent collaborator Jayson “Koko” Bridges. The track mimics the cadences of HBCU marching bands. The syncopated synth-horn blats land with funky precision. The rappers chant about "them Bad Boys comin'"; that and the occasional siren-whoops are the only connections to Bad Boys II. Everyone is just having too much fun to worry about maximizing the corporate synergy.

As with B2K's "Bump, Bump, Bump," P. Diddy didn't even bother to pretend that he'd written his "Shake Ya Tailfeather" verse. Instead, he gave songwriting credit to Varick "Smitty" Smith, the Miami rapper who also wrote his "Bump, Bump, Bump" lyrics. (Smitty's highest-charting single, 2005's "Diamonds On My Neck," peaked at #25.) On "Shake Ya Tailfeather," Smitty doesn't work too hard; you couldn't make up a line lazier than "I like how you dance, the way you fit in them pants." Later in his verse, Diddy goes back to the "pants" thing: "Mama, you're dead wrong for having them pants on/ Capris cut low, so when you shake it I see ya thong." It's all dumber than hell, but it's fun, too. Diddy mostly serves as a breather between the two St. Lunatics.

I love Murphy Lee's "Shake Ya Tailfeather" verse. Murph crams in multiple references to '80s cartoons: He-Man, Thundercats, Voltron. He makes puns out of the names of all four Hot Boys. He appreciates a "bangin' personality, conversate when the time right." (That "when time time right" almost seems like a legal disclaimer.) Murphy's rats come in packs like Sammy and Dean Martin, and he's got so many ki's you think he's valet parking. He sounds like he just loves rapping. I love it when rappers love rapping.

Diddy made plenty more hits after "Shake Ya Tailfeather," but he's never returned to #1. In 2004, Diddy rapped on his protege Mario Winans' heartbroken #2 hit "I Don't Wanna Know." (It's a 7.) In 2006, Diddy -- he'd dropped the "P." by then -- released his clubby Press Play album, which only sold gold. The biggest Press Play hit was "Come To Me," a collaboration with lead Pussycat Doll Nicole Scherzinger that peaked at #9. (It's a 6.) At that point, Diddy had made so much money from his Sean John clothing line that rap was basically just a hobby.

Press Play was Diddy's last solo album. In 2010, Diddy teamed up with singers Dawn Richard and Kalenna Harper to form a group called Diddy - Dirty Money and to release Last Train To Paris, a shockingly excellent album of futuristic electro-soul that didn't really sell. (Diddy - Dirty Money's biggest hit, "Coming Home," peaked at #11.) Diddy has kept himself culturally relevant, rapping on remixes and showing up in gossip pages for romantic entanglements and random-ass fights. He could always come back with another big hit. Earlier this year, Diddy reappeared on the Hot 100 for the first time in years when his Bryson Tiller collab "Gotta Move On" peaked at #79. He recently tried to change his name again -- to just "Love" this time -- but nobody listened.

Nelly followed "Shake Ya Tailfeather" with a Use Your Illusion-stye heat check. In 2004, Nelly released two albums, Sweat and Suit, on the same day. The idea was that Sweat would be all the uptempo club-jams while Suit would be the ballads. Both albums sold way less than Nelly's previous two. Sweat was an outright flop. It went platinum, but its biggest hit, the excessively horny Neptunes production "Flap Your Wings," peaked at #52. Surprisingly, Suit sold three times as many copies, and Nelly got to #3 when he teamed up with country star Tim McGraw for the graceful, low-key "Over And Over." (It's a 7.) Nelly's momentum had slowed, but it hadn't died.

As for Murphy Lee, he released his debut album Murphy's Law while "Shake Ya Tailfeather" was still at #1. "Shake Ya Tailfeather" also appeared on Murphy's Law, but that didn't seem to help sales. (The Bad Boys II soundtrack was already platinum by then.) Murphy's Law was a relative flop, and Murphy never became a star. But I've got to take a moment for Murphy's single, the Jermaine Dupri collab "Wat Da Hook Gon Be." Great song. The whole concept is Murphy claiming that he "don't need no fuckin' hook on this beat," but him saying that works as an amazing hook. It's a total magic trick. "Wat Da Hook Gon Be" peaked at #17, and Murphy Lee hasn't been back on the Hot 100 since.

Murphy Lee got to be famous for a summer or two, but he didn't get to stay famous. It's just one of those things. When a rapper first arrives as a supporting player, that rapper rarely gets a chance to become a proper star. Nelly arrived as a star, and he got to continue being a star. In this column, we'll see Nelly one more time.

GRADE: 8/10

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!

BONUS BEATS: You know what's funny? "Shake Ya Tailfeather" disappeared completely. You'd expect at least one prominent mixtape freestyle or something, but I can't find a thing. At the 2004 Super Bowl Halftime Show -- the Nipplegate one -- Nelly and Diddy performed together, but they didn't do "Shake Ya Tailfeather." Weird. If you like, you can relive that Halftime Show here:

The Number Ones: Twenty Chart-Topping Hits That Reveal The History Of Pop Music is out 11/15 via Hachette Books. You can pre-order it here.