In September, the shit really hit the fan(s). Brittany Aldean, wife of country star Jason Aldean and owner of her own fashion brand, posted a video of herself getting her hair and makeup done, and she punctuated it with some transphobic bullshit. She thanked her parents for not changing her gender when she went through her tomboy phase. Pushback was swift and merciless. Country singers Cassadee Pope and Joy Olakodun called Aldean out on her ignorance, but the most damning response came from Maren Morris, who tweeted, "It's so easy to, like, not be a scumbag human? Sell your clip-ins and zip it, Insurrection Barbie." In response, the former tomboy complained to Fox News, and non-country person Tucker Carlson slapped Morris with the sickest burn he could come up with: "lunatic country music person."

The dustup became a dividing line in Nashville. Fans at Aldean's October show in Nashville booed loudly when he mentioned Morris, while others criticized Miranda Lambert, presumably an LGBTQ ally, for sharing the stage and singing with him that night. Aldean's press company, the Green Room, dropped him as a client. To her credit, Morris owned up to what is essentially true — aren't we all lunatic country music people? — and printed her new slogan on T-shirts, along with the toll-free number for Trans Lifeline. She raised more than $150,000 for that organization and GLAAD Transgender Media Program. She was even affectionately enshrined in that Spirit Halloween meme. Morris handled the controversy well but never let folks forget that there were real stakes and real people imperiled by such a grievous misunderstanding of these issues.

Otherwise, it was a pretty slow year for country music. There was nothing like Tomatogate or Lil Nas X to make the genre take a good, long look at itself in the mirror. Instead, the Morris-Aldean kerfuffle only reinforced the rifts we already knew were present — between the left and the right, between the genre's reactionary history and its progressive potential. In the wake of the mass shooting in Uvalde, Texas, several country acts — including Lee Greenwood and Larry Gatlin — backed out of playing an NRA conference, but even that was more about optics than ideology. We might want to believe that Morris and Pope and Kacey Musgraves and Jason Isbell and the Highwomen (together and separately) and Margo Price and so many other country badasses have succeeded in pushing Nashville toward a less rigidly conservative stance, one that embraces rather than excludes non-white, non-cis, non-het artists and fans. We hope that books like Marissa Moss' Her Country and Francesca Rosyter's Black Country Music — two nonfiction standouts this year in any category — are changing the way people understand this beloved genre.

Check the charts and you'll find a very different story of contemporary country music. Disgraced singer Morgan Wallen, whose career took one big hit when he flaunted COVID protocols at Saturday Night Live and took an even bigger hit when a video leaked of him using a racist slur, spent nearly the entire year at the top of the album charts with Dangerous: The Double Album — a release that by now is almost two years old. It's not unlike Louis CK winning a Grammy or Dave Chappelle hosting SNL, all while pundits gripe about cancel culture. Wallen's chart reign would be a remarkable feat even for an artist who hadn't alienated so many listeners, but it doesn't speak well of any genre when one act can so thoroughly dominate for so long. Success in country music — real commercial success — is limited to smaller and smaller groups of artists, who it should go without saying are mostly male and mostly white. There is fine music on the charts, including excellent singles by Jimmie Allen ("Down Home") and dependable Cole Swindell ("She Had Me At Heads Carolina"), but it does feel like the industry gatekeepers are keeping the gates a little more tightly closed.

Those old rifts — between right and left, between struggling and successful — seem to be getting wider, although a few artists did try to bridge those gaps. HARDY, a Mississippi-born songwriter who's penned songs for Florida Georgia Line and Blake Shelton, hit big with the single "Wait In The Truck," a duet with Lainey Wilson, a self-proclaimed "hillbilly hippie" who makes wood-paneled country music. It's a Southern-gothic story-song about a regular dude who gives a ride to a "bruised and broke" young woman and ends up killing her abuser. It didn't drum up the same controversy that Garth Brooks' "The Thunder Rolls" did in 1992 or the Chicks' "Goodbye Earl" did in 2000, despite having very similar storylines. Is that a sign that Nashville has loosened up? Or maybe radio isn't too concerned when it's a regular dude playing the hero and dispensing the justice? Those older songs had the audacity to let the women off their tormentors themselves, but Wilson just waits in the truck and then visits her avenging angel in prison. It's a deeply regressive song masquerading as a deeply progressive song.

We also saw a lot of dudes with almost comically husky voices, some of whom stylize their names in all caps, like HARDY and ERNEST. It's bro-er than just bro country, an exaggerated macho twang where every note has to remind you that it's a real man singing. Even the usually reliable Luke Combs raised his voice this year: His big hit was "The Kind Of Love We Make," one of the least erotic slow jams ever committed to tape. How sexy is it hearing somebody yell at you, especially when he's yelling lines like, "Girl, I want it, gotta have it"? This kind of shoutiness gets mistaken for soulfulness, but more often than not (Zach Bryan being a notable exception) it just sounds shallow.

So 2022 is yet another year when fans had to do a little digging to find the most innovative and most fearless country music. The year was lousy with great albums and singles, yet most artists still have to hope the almighty algorithm puts their music into new ears. Same as it ever was, right? Not a single one of these complaints is new. Also not new: those glimmers of hope, those artists and singles to get really excited about. We got some excellent debuts from New Jersey's Breland, Arkansas' Bailey Bigger, California's Emily Nenni, Ireland's CMAT, Texas' Kimberly Kelly, and Plains, the country-leaning superduo of Jess Williamson and Waxahatchee's Katie Crutchfield.

Perhaps they'll be around as long as Willie Nelson and other veterans still making essential contributions to their sprawling catalogs. Nelson has barely slowed down lately, and while there's a little more grain in his voice, he remains a nimble guitarist even as he approaches 90. His latest, A Beautiful Time, is a meditation on aging and mortality — his own and everybody else's — but it's so generous and spirited that it never sounds morose or depressing. "I don't go to funerals," he declares, "and I won't go to mine." Lone Star stalwart Robert Earl Keen retired from the road, which is truly the end of an era, and his old friend and tourmate Lyle Lovett returned with his first album of big-band country in a decade, which bravely declared "Pants Is Overrated."

What are the odds that two of the finest country albums of 2022 would be tributes? Typically, those are among the most disposable releases, and you're lucky if you play as many songs as you skip. But Something Borrowed Something New celebrates the unspeakably sad songs of underrated troubadour John Anderson, with Dan Auerbach producing and John Prine covering "1959" in one of his final sessions. Two years after he took that fast train to heaven, Billy Joe Shaver got a tribute featuring a slew of Texas artists like Steve Earle, George Strait, and Amanda Shires (who got her start playing fiddle in Shaver's band). Each cover speaks to his graceful, simple melodies and sentimental lyrics, but the biggest surprise is a lovely version of "I Couldn't Be Me Without You" by Dallas-area native Edie Brickell (whose 1990 album Ghost Of A Dog belongs in the pantheon of great Lone Star albums).

We also got the welcome returns from artists too many years out of the spotlight. Sunny Sweeney released her first album in five years: Married Alone is a heartbreaking depiction of a relationship falling apart and the loneliness that follows. It's been just as long since we had a new Nikki Lane album, and her new one, Denim & Diamonds, was produced by Queen of the Stone Age Josh Homme — an odd pairing, but the glam-country strut of the title track made for one of the best singles of the year. Caitlin Rose released her second album back in 2013, and she finally followed it up with CAZIMI, an indie-country song cycle about everything that makes a follow-up so late.

Perhaps the unlikeliest trend is the rise of bluegrass, as a new generation of musicians with astounding chops shows just how malleable that form can be. Billy Strings marries the genre's instrumental derring-do to jam-band exuberance, but his new album, ME/AND/DAD, is a collection of family favorites that's both celebratory and deeply poignant. Crooked Tree, the new album by guitarist Molly Tuttle & Golden Highway, is a star-studded project in which the stars (Gillian Welch, Margo Price, Billy Strings) augment rather than obscure Tuttle's deft playing and sensitive songwriting.

From bluegrass to the Bluegrass State: This year it seemed like every mid-size city in Kentucky had its own amazing singer-songwriter: Joan Shelley from Louisville, S.G. Goodman from Murray, Ian Noe from Bowling Green, Kelsey Waldon from a place that's actually called Monkey's Eyebrow. Tyler Childers from Paintsville released a triple album featuring the same eight songs in three different settings — gospel, roots, countrypolitan — which makes it either a monument to indecision or a testament to just how wide his definition of country has become. Remarkably, most of these artists have resisted the urge to relocate to Nashville (maybe because Tennessee's politics are even more batshit than Kentucky's) and continue to find their inspiration close to home.

Some of the best country music this year came from well outside Nashville and the music industry, offering deeply complex and conflicted portraits of out-of-the-way places in America. Geography is perhaps the one thing that ties our top ten records together, and maybe that's what country music does best: It allows us to figure out where we come from and what that means. It helps us define home in all its complexity and contradictions.

Any guy from Kentucky who can crack a joke in an otherwise sad song is inevitably going to be compared to John Prine, although few bear up to such a standard. Bowling Green's Ian Noe is never as funny-ha-ha as his hero, but he strikes a similar balance between hardscrabble realism and blue-collar romanticism. River Fools & Mountain Saints, his second full-length, has the rough-and-tumble vibe of a front-porch session, the songs punctuated with rusty mandolin trills and rough-hewn harmonies, as though he and his band are playing by intuition and sheer gumption. With his barbed Bluegrass twang, Noe bears witness to the decay and beauty all around him, recounting the fates of too many river fools and mountain saints as they retire, get drunk alone, swim out of floods, wander around Kentucky and beyond. And in his cleverest flourish, he winds it all up with a heartfelt cover of Bonnie Tyler's "It's a Heartache."

An Iowa-born singer-songwriter with a clear, chiming voice, Hailey Whitters fills the songs on her third album with beautifully observed details about hometown boys who dream of Carhartt and chrome and family dinners where someone ends up preaching in the living room. It's an affectionate reminiscence of the home she left behind for Nashville, but it's a complicated one. Home isn't paradise, and it never sounds like a place she'd care to go back to. Instead, these songs comprise a loving tribute to the place the people that defined her: "If I take this love right to my grave," she sings, "it's 'cause I fall how I was raised."

A nonbinary, pansexual singer-songwriter who's been quietly releasing albums for more than a decade, Adeem is a seventh-generation North Carolinian who explores their sexuality and identity in country songs whose melodies suggest Lucinda Williams, whose wordplay echoes James McMurtry, and whose fuck-shit-up sense of humor brings to mind Todd Snider. Adeem owns up to the history of violence in their family on "Carolina," which ends with one of the most movingly compassionate lines of the year: "Some of us have childhoods that aren't poems on sight, but darlin', you're doin' alright." And "Run This Town" explains the debacle of Nashville politics, which squeezes out artists to make room for more condos: "We gotta run this town… straight into the goddamn ground!" Let the Adeem The Mayor campaign begin right now.

Lambert's evolution from Nashville Star runner-up to country superstar to Texas troubadour has been one of the most entertaining trajectories to watch, as she embraces the steely country-rock of Jerry Jeff Walker and George Strait as well as the song-forward country of Guy Clark and Townes Van Zandt. Palomino builds on the campfire ambience of last year's The Marfa Tapes but punches it up with a full band. In these songs the West is a place so big that she can cut loose or get lost or go skinnydipping in Lake Havasu with an old hippie she just met. "I want to see the desert from a painted palomino," she sings on "Actin' Up," and she makes it sound like her whole world rests on that wish. Lambert has reached a point in her career where her reliability and consistency have made it a little too easy to take her for granted, but Palomino suggests she's not done wandering, either geographically or musically. "I don't know where I belong," she sings on "Tourist," finding promise and defiance in a word that's too often used as a pejorative. "I might sound foolish but nowhere feels like home." Long may she roam.

Sure, it doesn't need to be a double album. And yeah, Wilco's return to country isn't really all that country. Despite the acoustic instruments, it's less about country as a sound and more about country as a concept. Tweedy uses the genre and our expectations of it to make a statement about where and how we're living. "I love my country," he sings on the title track, but immediately calls it "stupid and cruel." The music sounds sadder and sourer for being so lovely, so gentle, so wounded. The album showcases the chemistry between the band members (who recorded most of the songs in one take), especially on "Bird Without A Tail/Base Of My Skull" and "Many Worlds," as they bring Tweedy's musings to life. Best is "Ambulance," a quietly harrowing account of a near-death experience that I hope isn't based on his own life.

Sure, it doesn't really need to be a triple album. It probably doesn't even need to be a double. But credit this young Oklahoman for thinking big. He's got a robust, soulful voice and a sound that leaves some negative space in his arrangements, but his most winning attribute is his songwriting. On songs like "Something In The Orange" and "Whiskey Fever" and "Sun To Me," he rethinks conventional country drama, finding fresh new angles on age-old predicaments — watching a lover's car taillights disappear into the night, getting blackout drunk because numb is preferable to heartbroken, living with memories too painful not to worry over. His breakup songs never sound like one-sided conversations, though; rather, they're full of self-delusion and magical thinking, making clear that he's just as much to blame as the woman he's singing about. American Heartbreak, Bryan's major-label debut, is a grassroots success story, with a groundswell pushing the album to a number-five debut on the charts, despite not getting a physical release. It's clear that the sprawl is the point — not to prove himself as a songwriter (although there are 34 songs that do just that), but because his heart breaks too much for just two sides.

Is Amanda Shires even country anymore? She cut her teeth as a teen fiddler in Billy Joe Shaver's band in Texas, then moved to Nashville with a quirky brand of country. She found her greatest success with the Highwomen, but success as a solo artist has proved elusive. Her songs may have grown out of her background in country and Western, but they encompass Southern soul, torch songs, art-rock, psychedelia, avant-garde what-have-you. On "Hawk For The Dove" she distorts her fiddle until it sounds like a Sonic Youth guitar, and on the title track she emphasizes the subtle trill in her voice to convey mighty resiliency. That's what makes her seventh album so powerful: Rather than bemoan Nashville's disregard for women like her — who have the talent and temerity to remake country music in their own image — she takes it as a challenge, staring you down and daring you not to listen.

There are hundreds of small-town music scenes all over the country, where local players are putting their own spin on country, rock, and hip-hop influences. Murray, Kentucky, is home to Murray State University, a bustling postpunk scene, and S.G. Goodman, a singer-songwriter who combines Gang Of Four with Dolly Parton, angular guitars with high-lonesome Appalachian balladry. Teeth Marks, her second record under her own initials, toggles between the intimate storytelling of the title track and the abrasive working-class screed "Work Until I Die," as though all these different sounds are jostling for attention in her corner of Kentucky. What ties all these songs together, aside from their shared setting, is Goodman's richly grained voice, which sounds angry and bruised and compassionate and determined all at once.

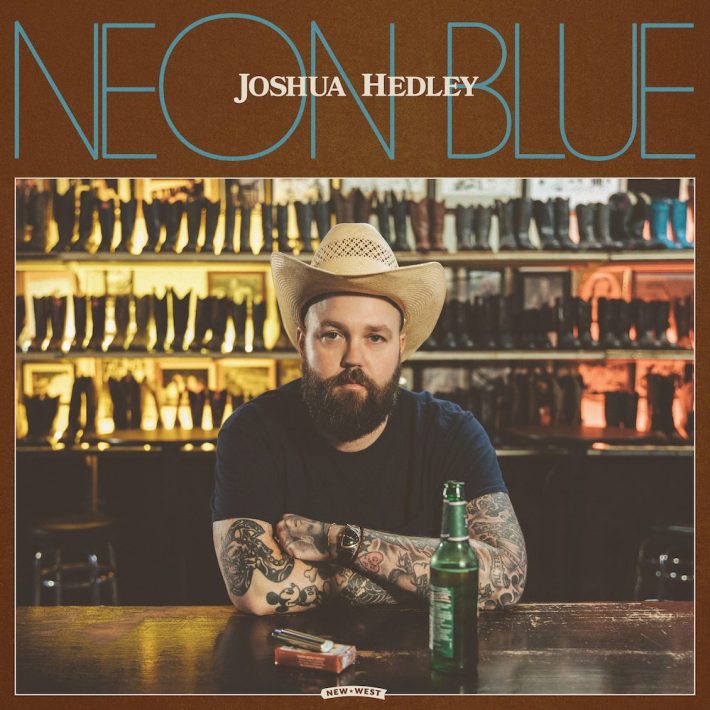

Hedley is both a Nashville insider and outsider. He's been holding down a residency at Robert's Western World for the better part of a decade, playing his old-school honkytonk in one of the city's last remaining old-school honkytonks. Proximity to so many pedal pubs and Instagram backdrops, however, only shows how out of place Hedley is on Broadway — not that he's trying to change that. His full-length debut, 2018's Mr. Jukebox, was a throwback to the classic country of the late 1950s and '60s, but Neon Blue updates his sound to the hat acts of the late 1980s and '90s. Derided by purists at the time, that rock-infused strain of twang, with its crackling electric guitars and unabashedly arena-size hooks, suits him well. With its stuttering chorus, opener "Broke Again" is one of the best singles of the year in any genre, and his cover of Roger Miller's "River In The Rain" ought to make No Fences-era Garth a little jealous. Apt for a guy who call himself a "a singing professor of country and western," he gets all the period-specific details just right, but the music's buzzy energy and his immense love for the form roots every song in the present.

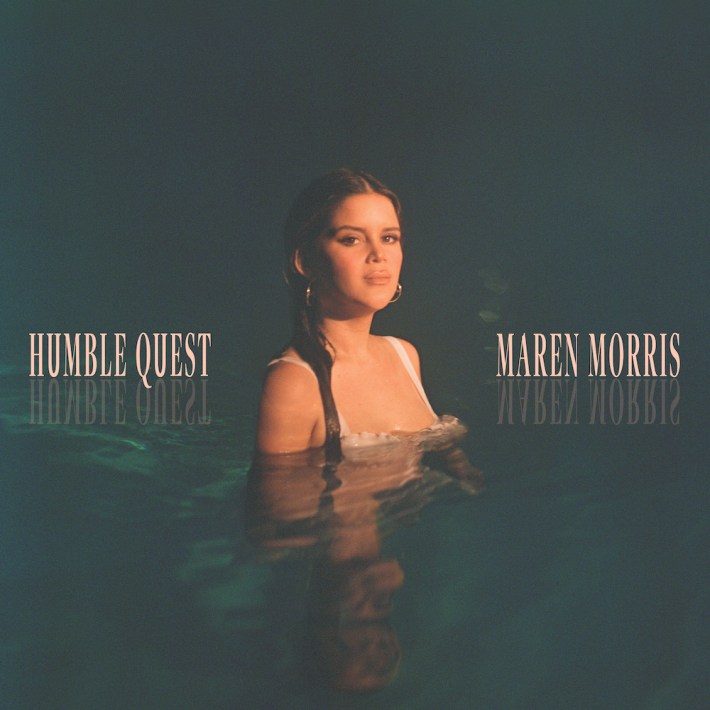

Morris was already a country music veteran by the time she arrived in Nashville. She'd been singing on stages around Arlington, Texas, since she was 10, and she'd released a handful of albums and earned several Entertainer of the Year Awards in the Lone Star State. None of that mattered when she packed up and moved to Tennessee, where she had to prove herself all over again. She commemorates that moment on "Circles Around This Town," in which she drives her beat-up Montero around town listening to burned CDs and writing songs in her head. She was looking for something worth writing about, and her humble quest became something worth writing about. Her sixth album is a loose meditation on the mania for writing songs: why she does it, what she gets out of it, and what those songs become over time. "Maybe all we'll ever be to them in a hundred years is three minutes in a car, in a bar, that says we were here," she sings on "Background Music," and she counts herself lucky to leave such a mark on the world. "Not everybody gets to leave a souvenir." All controversy aside, what made Humble Quest so moving in 2022 is that Morris shows what we all — artist and audience alike — invest in country music. (Bonus points for the In Rare Form version of the album, featuring stripped-down versions of these songs.)

Honorable mentions:

- American Aquarium- Chicamacomico

- Cory Branan - When I Go I Ghost

- Kaitlin Butts: What Else Can She Do

- Charley Crockett - The Man From Waco

- Deslondes - Ways & Means

- Sarah Lee Langford & Will Stewart - Bad Luck & Love

- Miko Marks & The Resurrectors - Feel Like Going Home

- Ashley McBryde - Lindeville

- Old Crow Medicine Show - Paint This Town

- Angel Olsen - Big Time

- Orville Peck - Bronco

- Sarah Shook & The Disarmers - Nightroamer

- Town Mountain - Lines In The Levee

- Lainey Wilson - Bell Bottom Country

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!