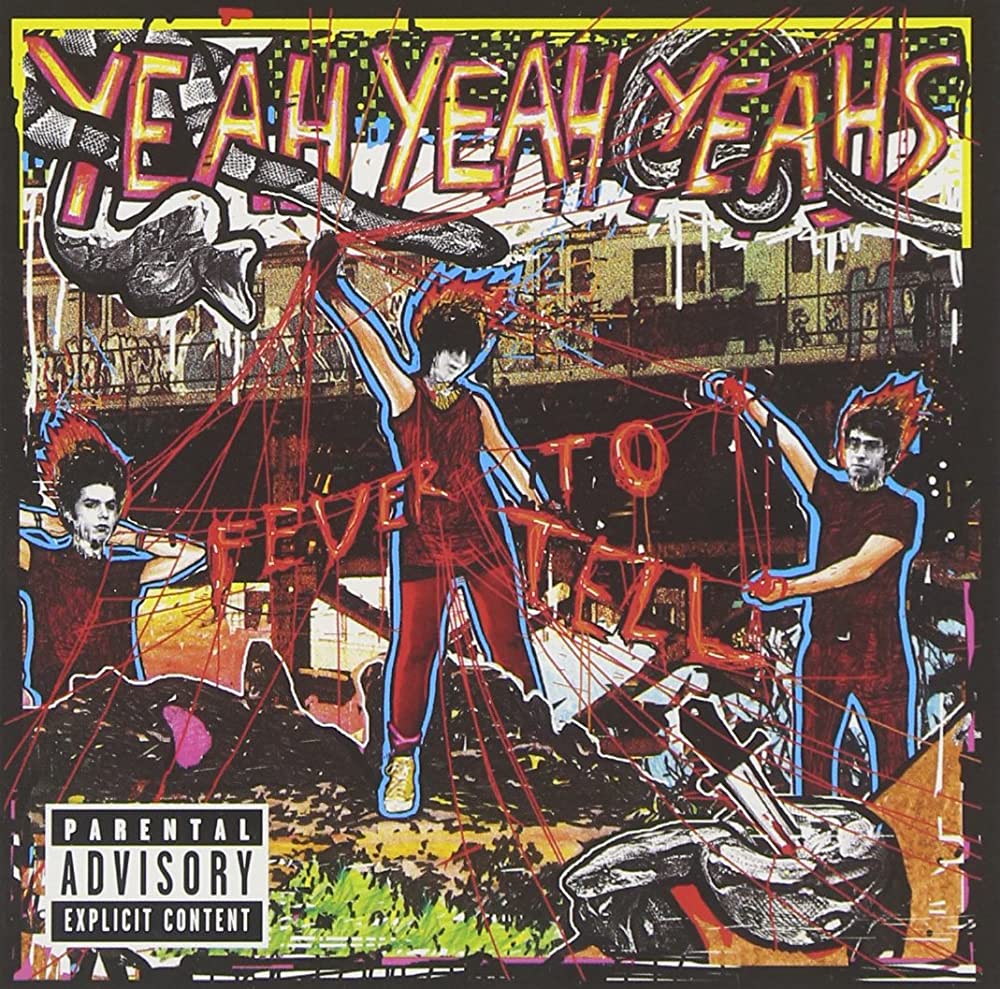

- Interscope

- 2003

"I'm rich." It's the first thing that Karen O sings on the first Yeah Yeah Yeahs album. Karen delivers that line in a sleepy murmur, over a Nick Zinner guitar riff that sounds like a malfunctioning sonar machine and a Brian Chase drumbeat that sounds like an ogre smashing two boulders together. Karen O extrapolates: "I'm rich, like a hot noise. Rich, rich, rich!" Then, her voice suddenly veers into a roar: "I'll take you out, boy! I'll take you out!" This was how the Yeah Yeah Yeahs introduced themselves to the larger world. As introductions go, that's pretty good.

Karen O wasn't actually rich when she recorded those lines, but she was working on it. The Yeah Yeah Yeahs were riding a deafening, overwhelming tide of hype, but that hype had not yet transformed into cold, hard cash. The YYYs' self-titled debut EP came out in summer 2001, and it turned them into the toast of the town. This was in the midst of the British press losing its shit over confidently decadent American bands like the Strokes and the White Stripes, and the YYYs rode that wave. Karen had been a shy college kid, but she knew how to present herself as a larger-than-life character -- wheeling across stages while whooping and screaming and spraying beer in every direction. Her bandmates played the background, but their scuzzed-up gutter-glam, built on the skeleton of '90s noise-rock, radiated electric-shock danger.

Few bands have ever been hyped the way the Yeah Yeah Yeahs were. But when it came time to finally make a full-length album, to stretch their legs and show what they could do, the YYYs didn't necessarily have full-on pop stardom in mind. Originally, they'd assumed that Fever To Tell, their debut LP, would come out on Touch And Go, the storied and doomed Midwestern indie label that had released the band's two EPs. They paid for the recording themselves, and they enlisted a friend as a co-producer.

Dave Sitek is famous now, but his band TV On The Radio hadn't even recorded their first Young Liars EP when he signed on to work on Fever To Tell. Instead, Sitek had been Karen O's co-worker at a Brooklyn clothing store, and he'd tour-managed the Yeah Yeah Yeahs on their first trips out of New York. In Lizzy Goodman's Meet Me In The Bathroom, Karen O says, "I guess he was just a buddy, and we immediately felt like we were family with him. And we didn't know anyone else. That was probably one of the biggest reasons we worked with him, because we didn't know anyone else." Sitek thought maybe the band was making a bad decision, but he rented a cheap Brooklyn studio, and they got to work.

At the time, the YYYs' hype was so overwhelming that the band was starting to crack. Karen O wouldn't take care of herself on the road; she'd drink like a fish and eat like a five-year-old. Eventually, after being whomped in the head by a falling stage monitor, Karen realized that she'd have to reel herself back in while performing, before she did any more serious damage to herself. The band toured as openers for Girls Against Boys and the Jon Spencer Blues Explosion, '90s underground bands that had helped develop the sense of swagger that would take the YYYs and their peers to the big time. Jon Spencer says that he and his friends referred to the openers as the "Maybe Maybe Maybes." That was because they had a habit of flaking out and cancelling shows, but you could also see it as a statement on the band's potential, on the questions about whether that potential would be realized.

Hype like that guarantees backlash, and the Yeah Yeah Yeahs had plenty of that. You can see it in the early reviews, even the ones that praise the band. The YYYs' swagger was, at least to some extent, affected. They were playing characters, archetypes. That's what virtually every successful musician does, but in the cosmology of that era's indie rock morality, that kind of theatricality might as well be the basest sin. Eventually, the hype got to be too much. At the last possible moment, the band backed out of a European tour, as well as an appearance at the UK's Reading Festival, so that they could finish Fever To Tell. Nick Zinner later remembered, "Karen totally put the brakes on and cancelled that shit. She was like, 'This whole thing is spiraling out of control, and we need to get a solid foundation first.'"

Fever To Tell did not come out on Touch And Go. Instead, the YYYs took an Interscope deal that guaranteed them both money and creative control. (Karen later said that Sonic Youth's Lee Ranaldo had advised them to go with a major.) The amazing thing about Fever To Tell, an album that will turn 20 on Saturday, is that it sounds like a band with a solid foundation that's also happily spiraling out of control. Most of Karen O's lyrics on Fever To Tell aren't linear, but they speak to some visceral emotional truth. She communicates through vivid imagery: thighs squeezed tight, sweat in the winter, a black tongue found at the mortuary, a man that makes you wanna kill and die, boys who are stupid bitches, girls who are no-good dicks. It's all over the place. It's great.

It wasn't immediately clear that the Yeah Yeah Yeahs were ready for prime time. I remember seeing the video for first single "Date With The Night" for the first time on late-night MTV2, thinking both that it ruled and that it might not work as a promotional tool. "Date With The Night," like a lot of the songs on Fever To Tell, is clearly the work of coked-up New York art kids who don't know or care much about selling pop music to the world. It's less hooky and immediate than most of the stuff on the first EP, and it presents the band as a force of giddy, sleazy, frenzied chaos. There's no structure, no sense of control. It's a wild-out anthem for the sake of wilding out -- "Ante Up" for kids with liberal arts degrees and H&M wardrobes.

What was the Interscope marketing department supposed to do with this? You couldn't even present the YYYs as a garage-rock band, since they really weren't that. They sounded less like the Kinks, more like the Fall. Nick Zinner's guitars flared and splintered. Brian Chase played drums like he'd imagined an alternate reality where John Bonham replaced Moe Tucker in the Velvet Underground. Karen O screamed about doing it to each other like a sister and a brother. "Date With The Night," the first single, has a chorus that's literally just Karen screeching, "Choke! Choke! Choke! Choke!" (For many years, I thought it was "Chop! Chop! Chop! Chop!" Same difference, really.)

Karen later said that the album was a product of post-9/11 anxiety: "There was this urgency, all of a sudden, for release. I was all about urgency, which was why we called that first record Fever To Tell. You never knew how long anything was going to last; every moment was ephemeral." Most of Fever To Tell stands as a monument to that urgency and ephemerality. It sound like being lost in the moment, like one of those nights where you find yourself running in a million different directions, never quite sure whether you're about to find yourself at an after-hours party where dudes are taking turns lighting each other's hair on fire. (I have vivid memories of ending up at a party like that around the time that Fever To Tell came out. Don't ask my why I was there; I don't remember.)

If all of Fever To Tell worked as a musical expression of that kind of headrush hedonism, that would be enough for the record to embody its moment, to ensure a place in history. We are, after all, in the midst of a revival of interest in indie sleaze, a phrase that nobody ever used at the time. Few records ever did the indie sleaze thing better than Fever To Tell. But the whole album didn't really work that way. One song stood out from the rest of the LP, from the rest of the band's catalogue, and from the rest of 21st-century rock music. You already know the one.

"Maps" didn't come out as a single until nearly a year after the release of Fever To Tell. Up until that point, the album wasn't really selling. It moved about 100,000 units -- tax write-off numbers for a label like Interscope at the time. The band was worried that "Maps" wasn't representative of the rest of the album, and they were right about that. "Maps" wasn't representative of anything else, except for the lost, hopeless, vulnerable-in-love feeling that the song captures so beautifully.

Karen O wrote her "Maps" lyrics about her then-boyfriend, Liars leader Angus Andrew. Both of those crazy kids had bands that were always on tour, and both were getting way more attention than they'd ever expected. Karen missed Angus terribly; the song's key line, "they don't love you like I love you," came directly from an email that she'd written him. The song builds elegantly and tenderly around that line, from the mosquito-buzz of guitar intro to the gentle echoes in the melody. On "Maps," Karen sounds like she's ripped herself open and exposed her guts to a judgment-happy world. In the song's video, a single tear slides down Karen's cheek in close-up, and that tear is very real. In Meet Me In The Bathroom, Karen says, "It was just a love song I wanted everyone to hear. And they heard it."

They sure did. To this day, "Maps" is still the Yeah Yeah Yeahs' biggest chart hit. (It peaked at #87, but still.) It's the song that eventually pushed Fever To Tell to gold status. It's the best YYYs song, and it's one of the best rock songs of this century. Somehow, "Maps" hits even harder in the context of the LP. After eight songs of giddy, sloppy abandon, Karen finally lays all her feelings out on the table, and they sit there, throbbing. A few other songs on Fever To Tell hint at that vulnerability, but none of them will swallow your soul like that one. "Maps" remains a one-of-one, an unrepeatable little miracle.

"Maps" remains the Yeah Yeah Yeahs' defining song, but it's not a pop song by most definitions. So it's funny that "Maps" still had a seismic and unintended effect on pop as a whole. One of the people who heard that song was Max Martin, the mysterious Swedish pop mastermind who'd been the primary songwriting engine behind the late-'90s teen-pop boom. Dr. Luke, Martin's now-disgraced collaborator, was listening to "Maps" with Martin one day. Luke later told Billboard, "We were listening to alternative and indie music and talking about some song. I said, 'Ah, I love this song,' and Max was like, 'If they would just write a damn pop chorus on it!' It was driving him nuts."

"Maps" does have a pop chorus, at least by YYYs standards. When Karen sings that they don't love you like she loves you, time stops. It's hard to ask what more you could want from a song. But that part of "Maps" doesn't explode out of the speakers like a neon volcano, and when Max Martin talks about a damn pop chorus, that's what he means. Dr. Luke suggested writing a song like "Maps," except adding an actual pop chorus. That writing exercise became Kelly Clarkson's "Since U Been Gone," arguably the greatest pop song of the decade. Karen O later told Rolling Stone how it felt to hear "Since U Been Gone": "It was like getting bitten by a poisonous varmint." And then: "Ah, well. If it wasn’t her, it just would’ve been Ashlee Simpson."

This wasn't the last time that "Maps" would inspire a much, much bigger pop song. Thirteen years after the release of Fever To Tell, Beyoncé assembled a group of songwriters that included Father John Misty, Diplo, and Vampire Weekend's Ezra Koenig to work on a track. That track became "Hold Up," and it had a chorus where Beyoncé sang that they don't love you like she loves you. This was Koenig's idea, and this time, the YYYs got writing credit.

Fever To Tell remains a glorious snapshot, a moment in time, and "Maps" is just one part of that. But "Maps" is the part that stuck, that lodged itself in the cultural consciousness forever. Whether or not they meant to, the Yeah Yeah Yeahs wrote something eternal -- something that's not even a tiny bit ephemeral. The Yeah Yeah Yeahs themselves aren't ephemeral, either. They've had a long and storied career, and they just put out a really good album last year. If they never come up with anything that resonates quite as deeply as "Maps," that's fine. Very few people ever will.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!