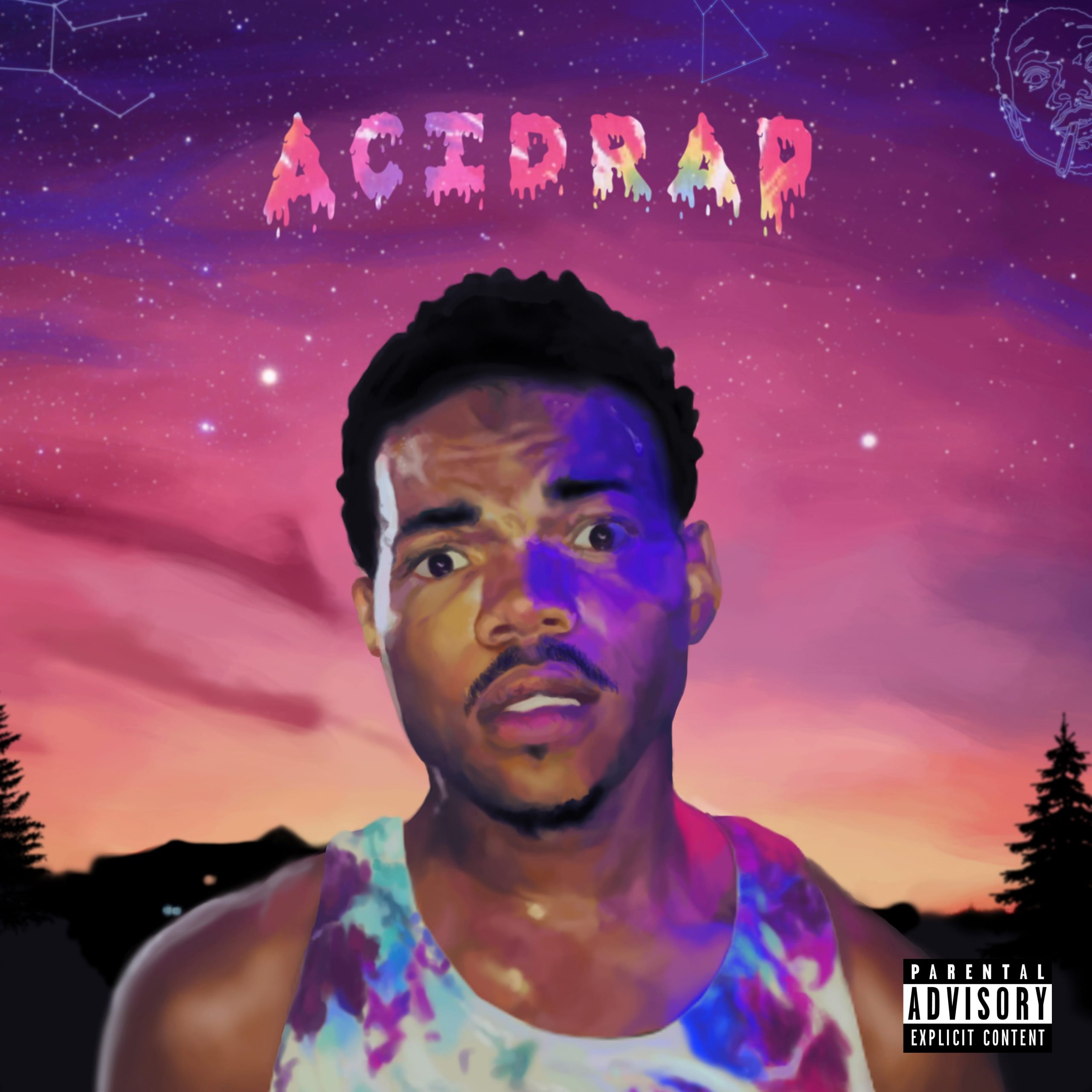

- Self-released

- 2013

Has anyone ever fumbled the bag as badly as Chance the Rapper?

Ten years ago this Sunday, a young Chicago native named Chancelor Bennett flipped the zeitgeist with his after-school special spectacle Acid Rap. The precocious rapper's second mixtape (we'd still be four projects and six more years away from a "debut album") was both a critical knockout and about as commercially successful as a free project could be, crashing download links upon release, charting on the strength of unaffiliated bootleg sales, and eventually going diamond on Datpiff. At 20 years old, it would have been understandable if the young creative turned into a recluse upon being thrust into fame, his appearance beggetting mobs in his city and drawing him instant, high-expectation comparisons to the likes of Lil Wayne, Eminem, and Kanye West.

Yet Chance took to stardom with eager abandon, capitalizing on every opportunity made available to him with so much exuberance he retained his charm rather than seeming craven. He used his new status to boost singles by local friends and peers, work with hip-hop icons like Erykah Badu and Busta Rhymes, and put on such euphoric live shows that every college campus in America raced to book him (he sadly outpaced my own university's budget before we could secure the deal). As an independent artist, Chance saturated markets across demographics in a manner the best PR teams could never dream of, performing everywhere from Saturday Night Live to Bonnaroo's SuperJam and establishing brand partnerships with everyone from Dockers and Adidas to the MySpace relaunch.

All his antics could have distracted from the music, but the music was too rich and fully realized to be overshadowed. As a writer, Chance was as prodigious as Nas on Illmatic, but infused his street tales with a hard-preserved sense of childhood wonder. In doing so, Chance showcased a thriving open mic culture that fit simultaneously within the loaded rage of Chicago's then-primary export of drill. Both scenes were fueled from the same dissatisfaction with the current state of their reality, but expressed those frustrations across opposite axes: defiant optimistic vs. revolutionary ignorance. The difference between a track like Chief Keef's "I Don't Like" and "Acid Rain" is more in diction than sentiment; Chance simply spelled out his terms more didactically, in a way that made the song more palatable for Obama to include on his annual summer playlist.

The overwhelming atmosphere of Acid Rap might be defined by the sing-along positivity of something like "Everybody's Something" or the incessant refrain of "I love you!" on "Interlude (That's Love)," but Chance frequently complicated this "easier-sang-than-acted-on" philosophy with moments of clarifying complexity. "But if you touch my brother/ All that anti-violence shit goes out the window along with you and the rest of your team," he huffs on "Acid Rain". Elsewhere he buries similar penchants for retribution in writerly exercises: "See them showing they teeth, that's just them flapping they gums/ If they bite and I'm snapping, clap clap, collapsing they lungs."

Chance rolls off Seussian flows like this constantly across Acid Rap, consonants cartoonishly smashed together using his squawking register, which might have been a barrier for some listeners but ultimately was received like a calling card. His technique was rigorous, yet the form was never a distraction from the content, which painted vivid portraits of psyches fractured between an infectious hometown pride and a seen-too-much sobriety. For as many of his dizzying stunts of dextrous syllable-slinging – "Tobacco-packing acrobat back-to-back packin' bags back and forth with fifths of Jack and fourths of weed, I'm back to pack on hands" – Chance would then hit you smack in the chest with a blunt passage of pained prose.

On "Cocoa Butter Kisses," he yearns to retain the image of innocence with his family that he is losing to his experiments with drugs. He wrestles with what it means to only have one life on "Chain Smoker," recognizing the incompatibility of his desire for a legacy with the risks of his lifestyle. "Paranoia," originally tied together with the more boastful and free-wheeling "Pusha Man" before the tape hit streaming, has so many gut-twisting couplets that I am tempted to just drop the lyrics below in full. But as a young rap fan, few verses stuck with me as much as the stoic interruption at the halfway point, set to a rickety and spacious Nosaj Thing production:

They murder kids here

Why you think they don't talk about it?

They deserted us here

Where the fuck is Matt Lauer at?

Somebody get Katie Couric in here

Probably scared of all the refugees

Look like we had a fuckin' hurricane here

The stark contrast of "Paranoia" following the one-two pop-rap punch of "Good Ass Intro" and "Pusha Man" was an intentional line in the sand to ensure listeners couldn't ignore the cracked concrete in which Chance had to grow himself out of. It was a provocation, something Chance has rarely allowed himself to issue towards listeners as his persona has further sanded down his contradictions. These days, he raps more like a condescending youth preacher than the aspirational older brother he first appeared as. With every feat of rap acrobatics he can still manage, he has never delivered a bar as affecting and insightful as the simple hum at the end of the song, "I know you scared/ You should ask us if we scared too."

Acid Rap was a rare consensus moment in rap, uniting fans across underground factions regardless of whether they were more geeked to hear a Twista or Childish Gambino feature. There was a little something for everyone's tastes, from a Slum Village interpolation to a Donny Hathaway sample (initially uncleared for streaming, but arriving on DSPs next week) to a Frank Ocean shoutout. The voracity of Chance's musical knowledge never felt forced, but like a true expression of love for a genre with such limitless possibilities that it contained room for all of Acid Rap’s dabbles into psychedelic soul, sunburnt jazz, and musical theater.

It's hard to remember today given the divergent paths of their careers, but Chance The Rapper was once lauded in the same breath as Kendrick Lamar as rap music's leading young innovator. Acid Rap was simply that remarkable upon arrival – a document of vibrancy within a city largely typecast for its history of violence and economic inequality. Chance was a folk hero, a man of the people who became the fixation of an online call to run for mayor of Chicago. He even came with the almost too-perfect mythology of recording his prior tape and first moment of spotlight 10 Day while suspended during his senior year for smoking weed. Despite occasional missteps in language or collaborators, there was an abundance of faith in him, and a sincere desire to see him succeed against the traditional music ecosystem that he positioned himself in opposition against.

Then, so gradually it escaped many listeners as it was happening, Chance's icarus wings began to peel off with his increased proximity to the sun. With age, it's easier to hear Surf and Coloring Book as fun but largely toothless, emphatic in sound but ephemeral in staying power. In the moment, however, critics wanted to coronate Chance so badly that they looked past his emerging limitations, claiming profundity where others heard a star retrenching into caricature. That he had fully lost the plot became unavoidable, however, when The Big Day arrived with the grandest thud in modern rap history, inviting fans to reconsider whether the standard thrust upon Chance was truly just runaway hyperbole.

Despite all that goodwill – which at that point included his own music festival in Chicago's Cellular Field, a feature on a number one DJ Khaled single, and reportedly pissing off the Weeknd because Abel didn't want to billed lower than him at Lollapalooza – Chance swiftly sidestepped the golden ticket laid before him towards a meteoric crater in his career. Critics were largely muted about the The Big Day; Stereogum's own Tom Breihan said it was not a disaster, but would have been more interesting had it been one. But the fan reception to the album was so apathetic to the point of antagonistic that Chance had to cancel an arena tour, fire his manager, and then claw his way back to relevance by playing judge on a Netflix rap competition and, less successfully, the host of Quibi's Punk'd reboot and the COVID-canceled Kids Choice Awards.

Without fully litigating the unproductive debate about whether The Big Day is as bad as its reputation suggests or a victim of an inevitable but unearned public backlash, I will say that it is clearly a demonstration of Chance's sound continuing to run its course to a final diminishment of returns. When it's not outright embarrassing ("Hot Shower," "Do You Remember"), it seems stuck in place, unable to move Chance in any compelling new direction.

Maybe the narrative was too easy to clown; Chance wanted to make an album about the rewards of marriage and family, and ended up getting dismissively labeled a "wife guy," the victim of memes so good they effectively eroded any room for nuance in what he might have actually accomplished (the memes are still coming four years later too; a whole trend unfolded on TikTok just a few weeks ago). The wide-eyed excitability of Acid Rap simply wore less well on the contemporary Chance, a fully grown public figure who now seemed unable to outgrow the childishness that was once an asset, now a crutch.

But if his sound went stale by The Big Day, the recipe has been iterated on since to offer a much longer shelf life. Mavi, MIKE, and ovrkast. all offer a more interesting evolution on Chance's soberly growth-oriented word density, while R&B acts like Yaya Bey and Jamilla Woods developed a more mature take on the cigarette-burned Crayola palette of the Social Experiment's production. As his own music became uninspired and too sickly sweet, more and more music born from the spark of Acid Rap flooded streaming services and festival bookings.

To his credit, Chance appears to have learned his lesson with his latest singles, suggesting a more mature and intentional record is waiting in the wings for later this summer. But even if Chance never fully recovers from his populist reckoning, he was still a net positive for pop culture. Many artists made and continue to make exceptional music pulling from Chance's bag of tricks, both affiliates like Saba and Noname as well as years-later upstarts like redveil and Tobe Nwigwe. His rising tide also lifted and launched several of his hometown boats, even if many of those individuals also proceeded to fumble their bags (Vic Mensa's whole career lives in the shadow of his best single; the less said about Towkio the better). House and gospel influences took on a prominent role in many rappers' sounds following Chance's wake, and while there's little good left to say about his father figure Kanye, his best modern day single was essentially a Chance showcase. It makes you wonder how Chance's career might have fared if his fabled Kanye-produced project Good Ass Job had actually been his next album instead of The Big Day.

Regardless, Chance's prophecy proved false; he met Kanye West and still failed. Very few artists can sustain the fire and intrigue of a world-altering breakthrough; the other proclaimed members of the new vanguard rising in 2013 have in time arguably lost their step as well, with Kendrick's cancel culture obsession turning bitter on (the still very good) Mr. Morale and Frank Ocean's mystique caving in on him earlier this month at Coachella. It's just that few artists have fallen as swiftly, both commercially and critically, with one bad project.

Yet no matter how much the culture has soured on him, Acid Rap still holds up, too packed with rapturous wordplay, heartfelt vocal performances, and ebullient production to rationalize even the staunchest cynic. While Chance is viewed today as an avatar of the perils of being too corny in pop culture, he had once shined so brightly he convinced us all that corniness was the most powerful way of being. I have no doubt what he managed to accomplish with Acid Rap will continue to rattle around in young rappers' music, much the same way The College Dropout or The Miseducation Of Lauryn Hill remain as oft-cited touchstones that license aspiring new artists to trust their instincts in deviating from contemporary trends. He fell off, but was by no means forgotten; what he couldn't sustain himself has continued to live a full life of its own.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!