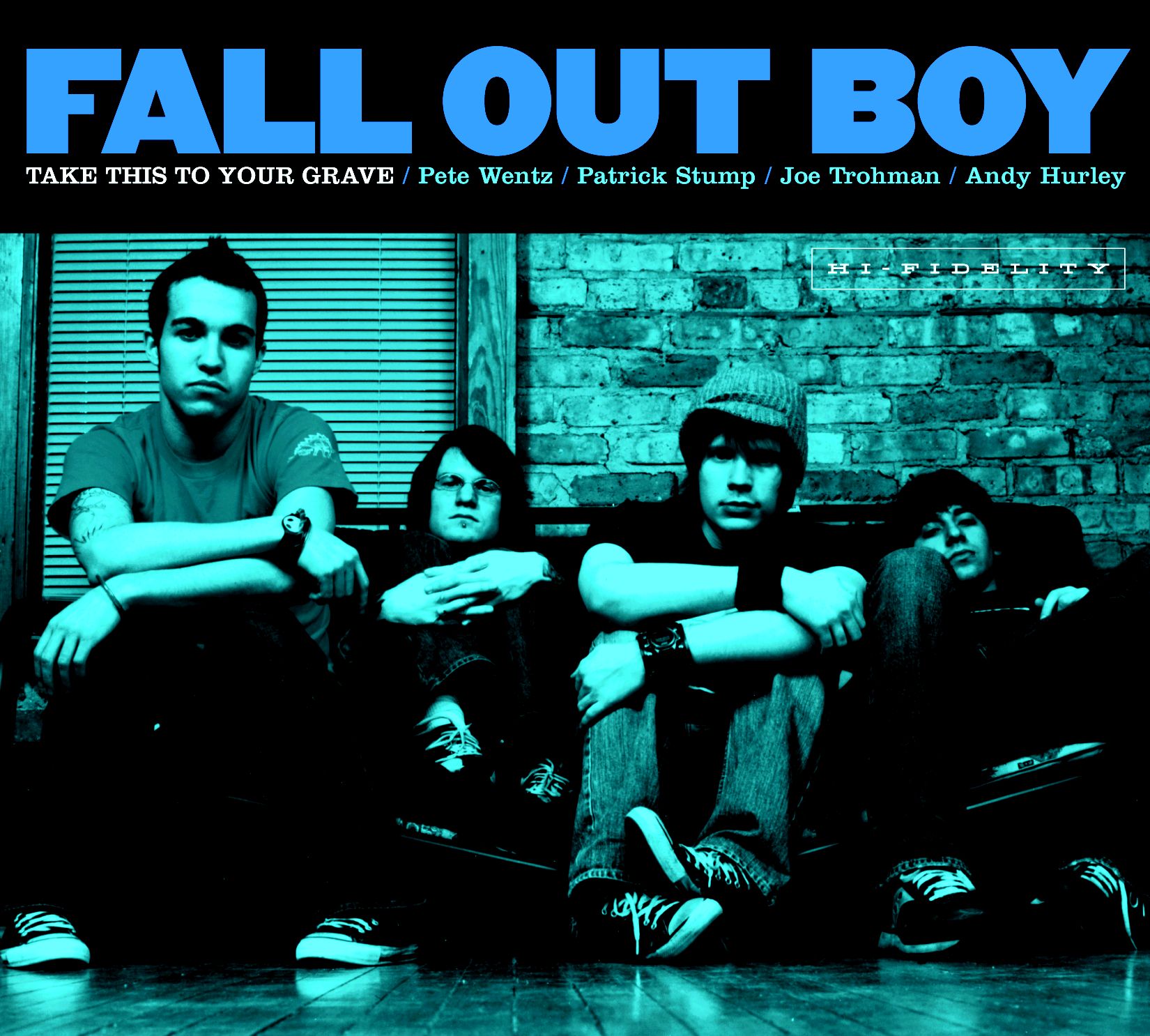

- Fueled By Ramen

- 2003

If you ever find yourself in Winnetka, Illinois, locate Sheridan Road and head due north. Keep walking; you’ll cross state lines before the street turns. As you approach Wisconsin, you might start to understand the maddening sameness that made Pete Wentz write songs about wishing his ex would drive off a bridge.

Fall Out Boy was meant to be a side project. Wentz was already a minor star in the Chicago hardcore scene by the time he and guitarist Joe Trohman started Fall Out Boy in 2001. He had become disillusioned by the community’s bands and fans, who he thought were too focused on “moshing and breakdowns” and had lost a “political” edge. At the same time, bands like Saves The Day and the Starting Line were breaking big with a softened variant of the genre, rooted in the same chugging riffs but tempered by clean vocals and hyper personal lyrics. Take This To Your Grave, which turns 20 this Saturday, was the outcome of Wentz’s desire to make something “easy and escapist.” The album opens with a song depicting highly detailed murder fantasies, but hey, we all have our own ideas of fun.

The band called Chicago their home — both in featuring their Roscoe Village apartment on the album cover and in direct references in songs — but they were really a product of the city’s northern suburbs. Wentz bonded with Trohman over growing up in the wealthy enclave of Winnetka. Trohman met singer Patrick Stump at a Wilmette Borders bookshop, where he interrupted a conversation to correct Trohman’s classification of the band Neurosis. And though its members played in bands with names like Racetraitor and XgrindingprocessX, Fall Out Boy’s sound was in a musical lineage — the Movielife, Taking Back Sunday — that captured the suburban monotony that amplifies heartbreak into visions of violent revenge.

Fall Out Boy released a split EP and a longer follow-up, Evening Out With Your Girlfriend, on the California hardcore label Uprising. The songs sounded rough — compressed, rushed, out of time and tune — but they introduced the irreverent self-deprecation that would come to define their lyrics, and more importantly, a glimmer of Stump’s outsized vocal ability. The band largely disowned the album, recorded in two days and released by Uprising without their approval. Commenting on Evening Out With Your Girlfriend in an Alternative Press oral history of Take This To Your Grave, Wentz said, “NASA didn’t go right to the moon: They did test flights in the desert. Those are our test flights in the desert.”

Logically, that would make Take This To Your Grave Fall Out Boy’s Apollo 11. Wentz, despite his insistence that the band was merely a way to blow off steam, was serious about finding a bigger label for their second chance at a first album. After a few near-deals with mid-sized shops like Drive-Thru, Fall Out Boy came to an unusual “incubator” agreement with Island Records: Island would fund their real debut, which would be released on Florida emo upstart Fueled By Ramen. If the record sold, they’d have the first chance to sign Fall Out Boy before they talked to competitors.

The deal was as cynical as it was charitable — indie credit was priceless social capital. Fall Out Boy had already recorded three songs with producer Sean O’Keefe at Smart Studios in Madison, which were originally meant for a split 7” with fellow Chicagoans 504 Plan. (Fun fact for anyone playing Fueled By Ramen bingo at home: 504 Plan’s later lineup included future Panic! At The Disco bassist Jon Walker.) With $18,000 from Island — and the addition of Project Rocket drummer Andy Hurley, who had drummed in the Smart Studio demos — Fall Out Boy returned to O’Keefe in Wisconsin, where they’d spend the next nine days writing the rest of the album.

By all accounts, it was a tense creative process. Stump had written most of the band’s lyrics until that point, and while his emphasis on cadence and syncopation made sense as a drummer and a vocalist, he in turn deemphasized the words themselves. Wentz wouldn’t stand for it, and after enough nitpicking, Stump snapped: “You just write the fucking lyrics, dude!” He did, writing about half the songs on the record. Still, Stump’s contributions became the majority of the album’s singles, likely because they relied on short hooks over verbosity (“Dead On Arrival”) and showcased his talent for elongating vowels until they become unintelligible (“Grand Theft Autumn”). Another Stump cut, “Chicago Is So Two Years Ago,” was a last-minute addition after O’Keefe heard Stump singing it to himself in the studio’s lobby. Stump and Wentz argued over every word, but the resulting song transcends their conflict; “There’s a light on in Chicago/ And I know I should be home” is their version of a hometown anthem, and as far as songs about Chicago go, it certainly has to be the only one that features vocals from Motion City Soundtrack’s Justin Pierre (whose verse was a surprise from O’Keefe to the band on the album’s final cut).

Listening back now, it’s easy to differentiate a Stump song from one written by Wentz — the former compared his friendships to The Goonies (“Saturday”); the latter wrote about new ways to torture the women that scorned him. Take album opener “Tell That Mick He Just Made My List of Things To Do Today” (a Rushmore reference, the band’s second): “Light that smoke, that one for giving up on me/ And one just 'cause they'll kill you sooner than my expectations,” Stump sings on the first line, and it just gets bleaker from there: “Let's play this game called ‘When you catch fire’/ I wouldn't piss to put you out.” It’s cartoonishly violent, but for their hormonal audience, Wentz’s penchant for drama was a draw, and he knew it: “My pen is the barrel of the gun/ Remind me which side you should be on,” he wrote on “The Pros And Cons Of Breathing.”

Fall Out Boy were objectively indistinguishable from the rising wave of scrawny, skinny jean-clad bands coming from the East Coast — a drummer, a bassist, a lead guitarist, a vocalist. But of course, they had a secret weapon: Patrick Stump, a short Irish Catholic man with mutton chops and golden pipes. Stump grew up on Elvis Costello and Nat King Cole; he accented Wentz’s despairing lyrics with bluesy crooning and falsettos that would later be a natural fit in duets with Elton John. When he belts out “Won’t find out!” on the final bridge of “Grand Theft Autumn,” he’s in conversation with Motown, not Midtown.

The band played like they had something to prove, blowing through 12 songs in just under 40 minutes. Hurley’s percussion elevated their sound from the sleepy, off-beat drums on Evening Out With Your Girlfriend, playing every fill like it could be his last. Wentz’s screaming, a vestige of his days as a frontman in metalcore group Arma Angelus, was a serrated edge that cut through Stump’s velvet voice. It didn’t necessarily benefit their sound, and the band would largely move away from harsh vocals in later albums. At the time, though, Wentz’s screams were his way of signaling that he hadn’t forgotten his hardcore roots, even if he’d soon leave them behind. Take This To Your Grave hinted at the heights Fall Out Boy could reach if they stopped fighting and shook off their hardcore baggage. The record’s sales reflected that potential; buoyed by magazine covers and a spot on Warped Tour, the band sold 200,000 copies of their debut while they were still technically just on Fueled By Ramen.

I can’t say I was aware of Fall Out Boy when they released Take This To Your Grave; I was seven years old and devoted to Junie B. Jones and John Mayer. But by their third album, 2007’s Infinity On High, I was the kind of rabid fan who would pull all-nighters on LiveJournal and Tumblr hunting down old interviews and absorbing Wentz’s questionable gender politics like a maudlin sponge. And before you judge me: Have you ever been 12? Fall Out Boy’s Take This To Your Grave is perfect for being 12, when you’re furious but not really sure why or at whom. Trapped in the cultural void of the suburbs, I saw Fall Out Boy’s music as a rich text, full of movie references, sexual innuendos, and the band’s musical inspirations. Between us, I first heard “Love Will Tear Us Apart” as a Fall Out Boy cover on their post-Take This To Your Grave, pre-From Under The Cork Tree acoustic EP, My Heart Will Always Be The B-Side To My Tongue (all right, judge me).

Returning to Take This To Your Grave now, I hear a band shaking off nerves, too busy playing fast to play well. But the songs also have a loose energy that they shed on their major label follow-up, 2005’s From Under The Cork Tree. Fall Out Boy would soon relocate to California, crash the pop charts, and ascend to tabloid celebrity. But on their debut, they’re still four guys from the Chicago suburbs, carving melodrama out of an endless stretch of Midwestern plains.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!