Drop Nineteens are back.

For three decades, singer-guitarist Greg Ackell was absolutely sure that those four words would never exist. Never. Ever!

"The one thing I was certain of, more than anything in my life, was that I would never make music again," Ackell stresses, vibrating with enthusiasm like a college professor mid-lecture. "I knew that more than I knew anything. And having now come back, it just goes to show me — that I know nothing!"

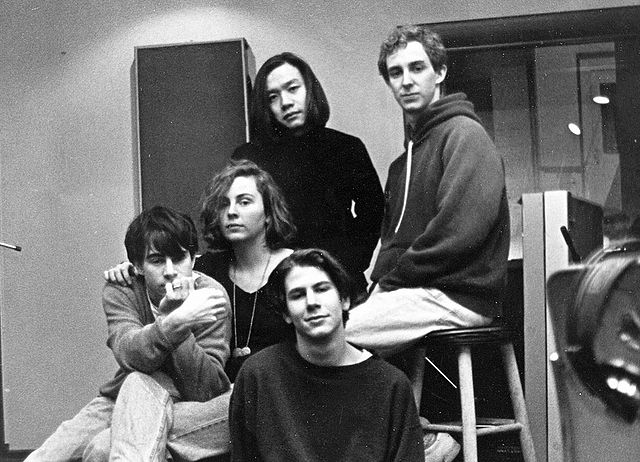

After forming as Boston University students in 1990, Drop Nineteens released two albums and a couple EPs before breaking up in 1995. In that time, they endured significant lineup turnover, and their sound changed dramatically between 1992's shoegaze pillar Delaware and 1993's largely forgotten National Coma. It was a whirlwind five years. Radiohead and the Cranberries opened for them. They toured with Blur and PJ Harvey. Their single "Winona" got played on MTV. They did coveted live sessions on BBC Radio One. They covered magazines. They were a big deal — and then they weren't.

But now they are again. In the intervening years, and the last half-decade in particular, scores of millennials and Zoomers have discovered their music online and become enraptured by it. Drop Nineteens boast nearly 140,000 monthly Spotify listeners, with millions of streams on tracks like the eight-minute bliss-binge "Kick The Tragedy" and the noise-pop dollop "Winona." All of that attention for a band who haven't performed since 1995, and whose records have never been reissued. Last year, London T-shirt boutique Jerks™ released a hyper-limited Delaware merch collection that sold out before the band's family members could even place their orders.

"After a roughly 30-year absence, we are learning daily what sort of audience we have and what to expect from them," the band wrote in a bewildered note to fans who missed out.

No Drop Nineteens lover ever expected the band to be up-and-running again, but then the bombshell arrived in January 2022. That month, Ackell posted an unprompted letter on Instagram announcing he and Drop Nineteens co-creator Steve Zimmerman had gotten the band back together. More than that: The whole reason for their re-emergence was because they'd written a brand new album, titled Hard Light. It arrives November 3 via Wharf Cat Records. They'll be returning to the stage later this year. And yes, Delaware and their other early material will be finally getting the long-awaited reissue treatment (eventually). But first comes the lead single from the new album, "Scapa Flow," out today.

Drop Nineteens' comeback was a monumental announcement for shoegaze-heads, but no one was more surprised than Ackell. The guitarist-singer-songwriter swore up and down for decades that despite enjoying his run as a musician, it was something he would never do again. Even when Drop Nineteens' popularity spiked on the internet. Even when so many of their pioneering shoegaze peers reformed in the 2010s and were welcomed back with big festival appearances and warm reviews. He didn't even consider the possibility of doing it again.

"It would come up," Ackell said of potential Drop Nineteens reunions. "I just would always completely shut it down. I didn't know how it applied. It didn't seem to be relevant to my life. I was very content and proud of those early days."

Suddenly, like a holy message beamed into his conscience from the god of glide-guitar, Ackell wondered what a modern Drop Nineteens song would sound like. The thing was, he hadn't owned a guitar for years. Ackell reached out to Zimmerman, who had unsuccessfully tried to coax his old bandmate into reunion mode for eons, and the bassist promptly overnight-shipped Ackell a shiny new Jazzmaster. From the moment Ackell took it out of the box, he started writing what would quickly shape into Hard Light. Still, he was apprehensive about publicly committing to a prospect he'd smacked down for years. But when outlets like Stereogum treated that humbly-posted return letter as breaking shoegaze news, he knew there was no turning back.

"It meant that I was doing this thing whether I liked it or not," Ackell admits. "I had to stick to it."

After all these decades stubbornly denying this moment, now that it's here, Ackell couldn't be more excited. So what the hell was he doing all these years that was so important that it consumed the attention he could've been giving to Drop Nineteens? Flowers.

"I sold a lot of flowers," Ackell says. "I had a flower company in New York City and different stores. I like to tell people that I've sold three things in my life: music, ice cream and flowers. That's why I sleep well at night. Who can argue with those three things?"

Ackell is on a Zoom call with me and fellow Drop Nineteens co-founder Paula Kelley, whose svelte sing-song provides the boy-girl balance that make Drop Nineteens' quintessential material so otherworldly and beautiful. For the entirety of our near-two-hour talk, Ackell is an eccentric chatterbox bursting with endearingly awkward zeal, his mind generating so many Drop Nineteens thoughts that he frequently stumbles over his words and has to regain his verbal footing. He only recently started speaking about this stuff in-depth for the first time in three decades, and he clearly has a lot to unload.

Kelley is bubbly and kind, with a squeaky voice and a bright blonde bob that glimmers in her soft office lighting. She doesn't talk as much as Ackell, but her bandmate repeatedly underscores her indisposable talents within Drop Nineteens, and praises the undeniable chemistry the two have as co-vocalists. In Ackell's words, the reunion couldn't have happened without getting Kelley onboard, which she quickly accepted after hearing the demos Ackell and Zimmerman sent her way.

"I knew it was going to be good. We don't suck!" she quips.

The rest of Drop Nineteens' current incarnation is effectively the Delaware lineup — Ackell, Kelley, Zimmerman and guitarist Motohiro "Moto" Yasue — minus OG drummer Chris Roof, whose role is amicably filled by National Coma-era drummer Pete Koeplin. The band recognize that Delaware is their definitive album, and they certainly had it in mind while crafting its 31-years-late sequel.

"It's the proverbial follow-up to Delaware," Ackell says of Hard Light. "It's different than Delaware, but it's every bit the ride that Delaware was. That is definitely paramount and testament to me, Paula, Steve, Moto and Pete doing this together."

Even when Drop Nineteens were still active, the prospect of those five people making another record was off the table. Three of the band's founding members left in the year after Delaware, including Kelley, who went on to play in other bands, make solo records and eventually put her classical piano background to use composing and arranging other people's songs. After that major exodus in 1993, Ackell and Zimmerman carried on with fresh recruits for their decidedly un-shoegazy follow-up, National Coma. Compared to the singular, squally brilliance of Delaware, National Coma is bland and unremarkable, with a very different alt-rock sound that's way more akin to Pixies than Pale Saints. It wasn't reviewed well after its release, and when the intra-band fighting ultimately resulted in Zimmerman departing, leaving Ackell the only founding member, the frontman glumly dragged Drop Nineteens to an unceremonious halt in 1995. From there, he decided to quit music.

"I was so down on the National Coma thing that I recorded something for myself, not even for release," Ackell reveals of the sophomore album's aftermath. "I knew that I was done and I wanted to stop making music, but I didn't want National Coma to be the last thing I ever did — just for my own listening purposes. And pretty much after that I just [stopped], and I seriously didn't touch a guitar."

The whole rise and fall of Drop Nineteens played out over a mere five-year timespan, and there wasn't a dull moment from the jump. Before they had played a single show or were even a functional band, they threw together their first demo (later included on the Mayfield demo comp) on a rented eight-track machine, recording mostly in dorm rooms. The band's biggest influences were English titans like the Cure, New Order, Echo And The Bunnymen and, of course, My Bloody Valentine, so Ackell shipped off cassettes to London's twin shoegaze empires, Creation Records and 4AD, with faint hopes of piquing their interest. Drop Nineteens were dumbfounded to get a positive call back within a mere week-and-a-half. Doubly so when, just a couple weeks later, the premier shoegaze bulletin, Britain's music weekly Melody Maker, gave them the coveted "Single Of The Week" slot for their cruddily-recorded demo song "Mayfield."

"I got a call and I was like, 'Single of the week? We don't have a record! We're not a band!," Ackell remembers. Before this, they weren't sure if Drop Nineteens would ever make it out of the dorm room, but Melody Maker’s plug sealed their fate. "It was like, 'OK, well I guess we're doing this now,'" Kelley recalls.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=DbJ2f9kaiQI

From there, a small-scale bidding war ensued, and Drop Nineteens ended up signing with Caroline Records in the US, despite their growing buzz in the UK, where the style of shoegaze they were making was at its apex. Their rapid ascendance to indie label signees and media darlings didn't make them any friends in Boston's alt-rock scene, which was swimming with bands who had spent years grinding for the success Drop Nineteens achieved overnight.

"We didn't pay our dues," Kelley half-jokes. Ackell elaborates. "Bands who were trying to make it, which was basically everybody, were out to get us," he says. "I think that's totally reasonable, I totally understand it."

They'd quickly earn the hype with Delaware, a shoegaze monument that ranks among the best in the genre's history. In Melody Maker’s shining 1992 review, the writer praised Drop Nineteens for how "menacing" they sounded compared to their "fey, drippy English counterparts like Chapterhouse, Verve, Slowdive, et al." Songs like "Happen" and "Reberrymemberer" have a Sonic Youth-ian bite, the latter even featuring pained screams in the post-hardcore style of Unwound and Unsane. Listeners in the UK regarded them as a sort of wild-west alternative to the dulcet English bands, but Drop Nineteens were commonly mistaken for anglos when they toured the US.

"It was just kind of considered British music," Ackell says of the way Americans perceived shoegaze in the early '90s. "So when we toured the US people assumed we were British. And it would annoy the fuck out of us. We were basically the American outlier in a largely British scene. When we played in Europe and England and stuff, they would delight that we were American, because it made us unique."

Of course, there were other American shoegaze bands existing parallel to Drop Nineteens (Lilys and Velocity Girl in DC, Medicine in LA, Loveliescrushing in Michigan, among others), but Ackell and Kelley earnestly admit that they weren't aware of most of those groups during their time — or at least didn't perceive them as part of an interstate shoegaze network. They didn't even tag along with their fellow Bostonians the Swirlies, who also cranked out ragged, decidedly un-British-sounding shoegaze concurrent to Drop Nineteens. In fact, Ackell has fond memories of working at an ice cream shop with Swirlies guitarist-vocalist Damon Tutunjian, where they bonded over music in between scoops. Even so, the two bands kept their distance.

"This was not a perceived scene at the time," Ackell emphasizes. "Looking back, I totally get it. Swirlies and Drop Nineteens in 1992 in Boston, that was a fucking scene. I'm telling you it wasn't. We never played together. This all got realized years later. Like, oh, that was a thing."

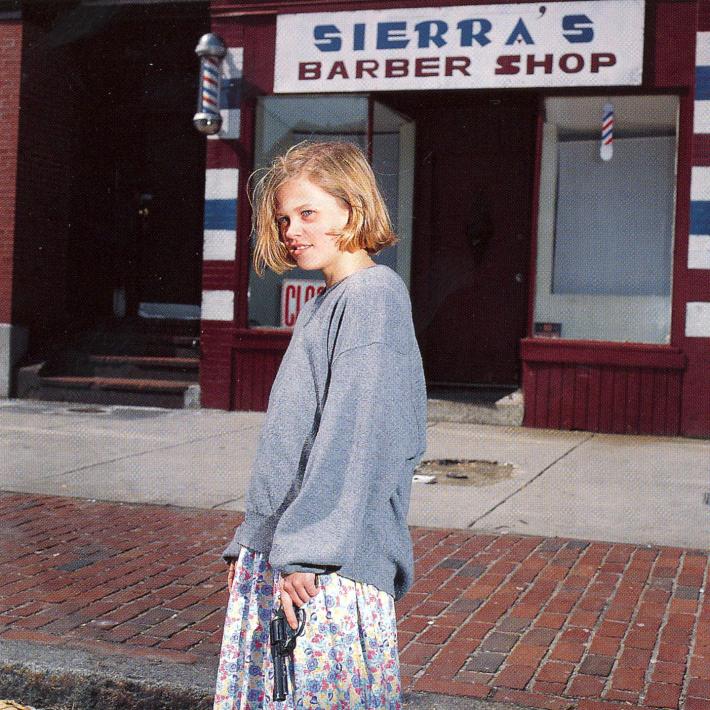

Ironically, the band have a firmer sonic and aesthetic foothold in today's American shoegaze landscape. The strikingly aggro cover art for Delaware — a photo of a tween girl holding a revolver in front of a barber shop, grinning like she just did something irreversibly bad — looks more in-touch with the present-day shoegaze vibes than the plush mosaics that adorned early-90s classics like Loveless, Just For A Day, and Nowhere.

Today, shoegaze breakouts like North Carolina's Wednesday relish in indecent tales about cops seizing "guns and cocaine" from neighbor's houses, and Philly trend-setters They Are Gutting A Body Of Water plaster their flyers and merch with abrasive graffiti fonts and murderous artillery of all calibers. Unlike shoegaze's foundational years in the early 1990s, the US is ground zero for shoegaze's explosive new wave, and it's no wonder that Delaware’s hard-edged look and sound resonate with modern-day audiences. (Notably, Drop Nineteens have pledged to change the iconic cover art for the upcoming Delaware reissue, as they feel a kid holding a gun rings distasteful in the mass shooting era.)

As indebted as Delaware is to My Bloody Valentine's particular blend of gale-force guitars and bleary, seafaring rhythms — especially "Kick The Tragedy," which rides its hypnotic groove for over six minutes in a blatant nod to Loveless closer "Soon" — Delaware really did carve Drop Nineteens' own niche into a genre that was nearing its first creative plateau.

Part of that may have been due to the album's construction. While there was plenty of worthwhile material to mine from their first couple demos, the band explicitly vowed to not re-record any of those early songs, and instead built the entire album as they were recording in the studio. Therefore, Ackell characterizes many of the tracks as "experiments" rather than traditionally written-out songs. What they cooked up is exactly what you hear on the record. There were no first drafts.

"No demos exist of any of those [Delaware] songs," Ackell says. "We kind of wish we had some these days because everyone's talking about re-releasing Delaware and what the extras will be. But there's no demos or unreleased material from Delaware. Doesn't exist."

Even though it was released just one year later, National Coma doesn't feel especially relevant to Drop Nineteens' legacy. Like so many of their across-the-pond contemporaries who eventually stripped away the effects for a polished Britpop sound, Drop Nineteens took a radically different, more streamlined rock approach on National Coma, losing their signature magic in the process. Both Ackell and Kelley feel that the Your Aqarium EP they released right after Delaware (featuring a roiling full-band version of the euphonious Delaware delight, "My Aquarium") represents where they would've gone if Kelley and Co. had remained in the band. One of their main goals for Hard Light was to give Drop Nineteens fans — and themselves — the next step they never took on National Coma.

"I didn't really want to make it like Delaware," Ackell says. "I wanted to follow up Delaware in a way in which we never did. Technically, National Coma is the follow-up to Delaware, but it doesn't follow it up in any manner. It's not a natural progression from it, it's a complete inversion of it. On this one, I wanted to follow the ethos of it."

The band succeeded. Hard Light’s 11 songs don't sound like Drop Nineteens attempting to regurgitate the same creative ideas they spawned in their late teens, but it sounds reverent of Delaware’s eminent charm. To once again invoke My Bloody Valentine — another shoegaze band who released two albums and then dipped for several generations before returning with a follow-up — Hard Light feels spiritually akin to 2013's m b v. There're new ideas. It's obviously a maturation. But it sounds like a logical progression of their artistic evolution, whereas National Coma was a rejection of it.

"We didn't set out to make a great shoegaze record," Ackell says of Hard Light. "We set out to make a great record."

Below, Ackell and Kelley discuss more Delaware memories, the band's tumultuous first run, why they finally got back together, what to expect from Hard Light, and whether or not they'll go away for another 28 years.

Delaware just turned 30 last year. Many people consider that a shoegaze classic today. What do you make of that pedigree?

ACKELL: I didn't know what to think about that record for a long time, or really any of our records. I certainly didn't feel that way about it for a long time. I appreciate that it's kind of come back and gets recognized as such. It got recognized at the time as well, it was very well-reviewed. Of course, I learned that because we released another record that was not well-reviewed, and I have something to compare it to.

Delaware was highly lauded at the time, but in the early days, a band like us would come along, release records and then slowly but surely they'd go out of distribution, and everything about it would fade away. And it would be gone, and I was kind of always accepting of that. I liked it, even. That I did this thing earlier in my life and I was proud of it, but it wouldn't be my whole life.

The internet comes along and now you can discover everything that ever existed. And that is what has brought Delaware back. But it's interesting to me because it meant dealing with something that I wasn't thinking about for a long time. So Delaware is something now that's on a lot of people's minds, but for a very long time it wasn't on anyone's mind. Including my own.

KELLEY: I was really surprised [about the comeback]. At the time I had no idea, it was such a whirlwind. In retrospect I'm really glad I was able to be a part of [Delaware]. When we were in the studio talking about it, I was so sick, I had the flu and I remember just being there trying to sing "My Aquarium" just croaking it out.

Back then, you guys had this hype in England, and you signed to a legit indie label. Did you want to be a career band with Delaware? Did you want to become a band on MTV or did that just happen?

ACKELL: Here's what I'd say about this: Be careful what you wish for. I was very, very driven to make a record and be a band.

KELLEY: He was up 'til five in the morning working all the time.

ACKELL: What never occurred to me is whether I wanted to do it for the rest of my life. It didn't occur to me to think of what would happen if I made a record, because all I wanted to do was make a record. So then you get to that point and you make a record, and then it even does well! Now what do I want? I just never considered any of those things and it's one of the reasons why I stopped doing it. It's one of the reasons why I took a 30-year break. I don't think I did want to do it for my life.

So after Delaware, there's a big lineup change. What happened there?

ACKELL: Being 19, on the road, having a successful record, and I didn't think past getting a record out. I was a little lost, I think.

KELLEY: I quit the band.

Why'd you quit, Paula?

KELLEY: I don't think I admitted this then, but I don't think I really enjoyed being on the road in a foreign country. I didn't know shit about life and I just kind of freaked out. If I had my wits about me I never would've quit in the middle of a tour. I finished out the tour but I said I was gonna quit.

ACKELL: I wasn't handling things that well. We were ridiculous kids. You get in a spat with the drummer and say, "Well fuck you, I'll replace you!" That kind of mentality. So then there were all new people, and that kind of fell apart and I didn't even treat those people that well. Again, there just wasn't a lot of foresight on my part. I wasn't planning to do this, and I don't think I was really built to do it.

Sound-wise, National Coma is a big departure from Delaware. Was that because of the new members or were you like, "Oh, fuck the sound of Delaware."

ACKELL: A little bit of both. I was always trying to run in another direction. I think my idea was, "Oh, you like Delaware? Fuck you. You don't like it for the right reasons." Which is kind of insane. That was my mentality back then. I don't think it was skirting some kind of fashion to change up the sound, so much as it was trying to explore another thing.

Coming back now, we recognize that Delaware is the indelible sound of the band. I probably could've called [National Coma] a side project and Drop Nineteens never made a second record.

When did you realize that Delaware had taken on this new life long after the band had broken up? The mid-2000s? The 2010s?

ACKELL: I never wanted to hear about it. It wasn't because it was a sore subject, I just wasn't interested in it. Steve would reach out to me and say, "Hey Greg, people are listening and talking about this," and anytime he sent me anything I wasn't interested. I really didn't want to know. It's appreciated, don't get me wrong. There's no doubt that it's flattering. I don't know how it applies to me, is what I'm getting at.

KELLEY: Yeah, it's like, we didn't really work for this snowballing. It's a passive thing and we look and say, "Oh wow."

ACKELL: Yeah, what have we fucking done for that record for the last 30 years? Nothing! So it's a little bit out of our hands in a way. But that might be changing because we're going to tour and play those songs. So finally we're gonna earn our fucking keep.

KELLEY: We're finally paying our dues!

Were there amends that had to be made between you guys as you all got back together? Any tension to be quelled?

ACKELL: No, not yet.

KELLEY: We didn't sit down to smooth over the relationship, but we did have some conversation that was like, "Ah, I was kind of an asshole then. Yeah, me too, whatever."

ACKELL: I'm having the time of my life being back in conversation with these people in Drop Nineteens. It has been an unexpected turn in my life that's amazing. It hasn't occurred to us to work out some problem because there is no problem anymore. We're adults and know how to treat each other with respect and not be fucking ridiculous people.

So why did it finally happen?

ACKELL: I wish I had an answer for you. I've thought really hard about it and I just don't have an answer, man. It just occurred to me. I can't explain it other than to say that I got a call from someone raising the prospect, like it had happened over the years, and every single time I'd shut it down. This one time I got off the phone and I thought to myself, what would a modern Drop Nineteens song sound like? I wanted to hear it — for the first time.

Then, I talked to Steve, and he had been thinking what it might sound like, and I had some ideas. And then all of the sudden we were going to do it. I had to do it to find out what it would sound like. But why now? I just don't have an answer.

Were you receptive right off the bat when Greg reached out, Paula?

KELLEY: I was trying to figure out why in fact I said yes — and I think I figured it out. When I said I always knew I was going to do music, that's been true for a young age. But I got sober 10 years ago. When I got sober my entire coping mechanism is gone, and I was just terrified of everything for years. I was a recluse and I didn't know if I was ever going to be able to make music again. I wasn't writing songs. I just thought, "Okay, I'm done with that." I could still do arrangements for people, but I wasn't promoting myself. It was dark.

In the last two or three years I finally came out of it. I kind of realized how to be a person again. And I started writing, and I'm just so grateful that that happened. So when [Greg] approached me, it was just the right time. I was like, "Alright, I'm doing music. I'm doing this shit."

Greg, did you basically have to re-teach yourself how to play from scratch?

ACKELL: When I decided to do this, I told Steve, "I don't have a guitar." He overnighted a Jazzmaster to me.

KELLEY: That's a friend.

ACKELL: He wanted to put a guitar in my hand. First time in 30 years I'm saying I'm gonna do this, I think he wanted to close the deal. This is a true story. I get the guitar and I know how to tune a guitar to itself. I know [how to tune each string to the next]. But I didn't know what a low "E" was and I don't have a tuner, so I just tuned it to itself coming out of the box. And it was in drop C#. No, not drop C# the tuning, but the low "E" is "C#."

So this whole album is in drop C#, because when I started writing — literally that moment, when I picked up the guitar and tuned it to itself, I started writing these songs and I started singing to it. And I liked the sound of it. I liked the sound of my voice in a lower cadence, because it's tuned lower. That's how poor a musician I am. I get it done, but I didn't know what an "E" was. But it turned out well, and this album has a particular sound because of that occurrence.

How did you approach Hard Light in a way that feels quintessentially Drop Nineteens to you after all these years?

ACKELL: Like I said, I think Paula and I's voice is a big, big part of it. I think that's the indelible sound. With Megan [Gilbert], who was on the second record, I loved her voice. I thought it was a beautiful voice. But I think the Delaware sound is me and Paula. But don't get me wrong, this is a different sounding record than Delaware.

Delaware is a more live-sounding record. There's a little more rocking out, a song like "Angel" for example. We do some of that here but it's a little more nuanced. And there's some vulnerabilities on this new album that are cool. It's got mood, I think. We bring the feels on it.

I think a song like "Scapa Flow," for example, does sound like it could be on Delaware. It has those guitars, it has that amazing bass sound that Steve gets. He does this thing with his bass, we call it kind of a flutter, and the way he strums it. There's just nobody who does that.

The thing I recognize about Delaware is that it's an eclectic ride. You don't know what's coming next. I would say that on Hard Light, there's a little less experimentation. Because we were just more interested in songs this time. They're just more developed than some of the things on Delaware.

KELLEY: It's more cohesive. And also I think it's more earnest. Not that Delaware was phony, but there were a couple tongue-in-cheek things and it was "cool." You mentioned a vulnerability [on Hard Light]. It's warmer.

What about this record feels vulnerable to you?

ACKELL: The way I write lyrics is… I'm pretty guarded.I don't always want people to know what's going on, even Paula…But on this record, there're some love songs. "Tarantula" is a straight-up love song to my girlfriend, and so is "T." A song like "Lookout"... that's some pretty heavy lyrics, and it's pretty revealing for me. Even the opening track, which is one of Paula's favorites…It's just emotional sounding.

KELLEY: Even without the lyrics, the music itself [is emotional].

When did you decide that you were going to play shows again?

ACKELL: It just sort of follows. It certainly wasn't [the plan] at the beginning of this. It's just, this is what bands do now. We want to play some of these songs for people. And we're also acutely aware that a lot of people that care about this band were convinced they were never going to get to hear us play these songs. And they were right about that! The fact that we're together again and that we're going to do it is, to me, not a miracle, but it's very unexpected. And so I think that's something to treat seriously. We appreciate that opportunity.

We're playing a handful of dates, East Coast and West Coast — we only want to play in cities that want us. And we'll see how it goes. For example, "Kick The Tragedy." We basically never played that song live. That song has legs, I don't have to tell you. It's hard to avoid hearing about that song if you're Greg from Drop Nineteens. So going out live, we have to play that. And that is a curious thing for us. We're going to fucking make that shit work because we never really tried before. We dismissed that song back then. I remember a few people asking for it in audiences, but we didn't fucking play it. And we're gonna play it on this tour, and it's gonna be good.

And this could be it. I remember Robert Smith of the Cure constantly saying that all the time, "This is it." Every night he'd say, "That's the last time you'll ever see me."

KELLEY: I've seen so many "last" Cure shows.

ACKELL: And I don't think he's lying, I think he means it. And I'm not lying here, this could be it. Maybe our promoter doesn't want to hear that, but we could do these shows and that's it forever, and I'd be fine with that. Because we did not expect to be doing this in the first place.

Obviously you haven't even put Hard Light out yet, but is the door open for more music?

ACKELL: Steve will not stop talking about new music and I'm like, "Steve, what new music?" He's like, "On the next one," and I'm like, "This one isn't out, there's not even a this one! And by the way, if what you have is so fucking good, why isn't it on this one?" I tease him.

I could absolutely see [us] doing this [more] because like I said, what's been surprising and good for me is to realize I had something to offer. And that's been rewarding for me. Because I didn't know before I did this that I still had something to offer, musically. And it turns out I did. So based on that, maybe there's something else after this.

KELLEY: If people want us, that's a gift. So I'm not gonna rule anything out.

TRACKLIST:

01 "Hard Light"

02 "Scapa Flow"

03 "Gal"

04 "Tarantula"

05 "The Price Was High"

06 "Rose With Smoke"

07 "A Hitch"

08 "Lookout"

09 "Another One Another"

10 "Policeman Getting Lost"

11 "T"

TOUR DATES:

October 10 - Washington, DC @ The Atlantis w/ Greg Mendez

October 11 - Philadelphia, PA @ Union Transfer w/ Horse Jumper Of Love

October 12 - Boston, MA @ The Paradise w/ Greg Mendez

October 13 - Brooklyn, NY @ Warsaw w/ Greg Mendez

October 19 - Los Angeles, CA @ The Belasco w/ Winter

October 22 - Oakland, CA @ The New Parish w/ Winter

Hard Light is out 11/3 on Wharf Cat. Pre-order it here.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!