On this day in 1973, a young lady named Cindy Campbell held a back-to-school birthday party in the rec room of 1520 Sedgwick Avenue, an apartment building in the Morris Heights neighborhood of the South Bronx. The entertainment for the evening was Cindy's 18-year-old big brother Clive, who went by the name DJ Kool Herc. Herc was born in Jamaica, where he absorbed reggae's soundsystem culture before moving the the Bronx with his family at age 12. Learning to DJ on his own, Kool Herc came up with a technique where he'd switch back and forth between double copies of the same record, extending drum-heavy breakdowns into infinity. At that birthday party, he demonstrated what he could do.

The truth is that there is no one moment when hip-hop began. Genres of music don't work that way. It's not one person having a moment of lightning-bolt inspiration, or at least it's not just that. Ideas build on other ideas. People steal from each other. Communities form and dissipate. Often, you can hear echoes of a new genre years or even decades before anyone acknowledges that genre's existence. There are many, many people who could claim that they invented rap music, or at least helped to invent rap music: James Brown, Gil Scott-Heron, the Last Poets, Rudy Ray Moore, Blowfly, plenty of others. Rap music flourished as more than just a local South Bronx phenomenon partly because people were able to connect this new music with its most familiar aspects.

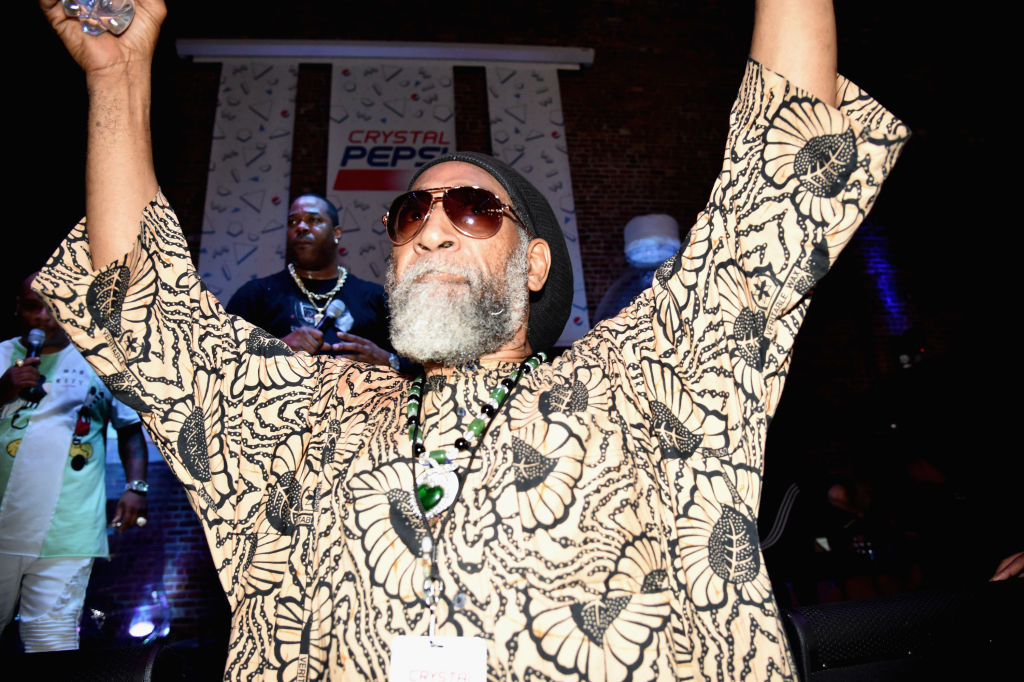

Nevertheless, that 1520 Sedgwick Avenue party was, by all accounts, a huge moment. Kool Herc's idea to extend the break was a real innovation. At that same party, someone -- maybe Coke La Rock, maybe Kool Herc himself -- rapped over those breaks, a new mutation of an old vocal technique. Plenty of pivotal rap figures claimed that they were there on that night. Since then, Kool Herc has auctioned off his memorabilia, and he's attended a ceremony where that stretch of Sedgwick Ave. was renamed Hip-Hop Boulevard. He's about to be inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame.

Within a few years of that house party, crews of DJs and rappers flourished all over the South Bronx, and the phenomenon got a huge boost when the 1977 blackout allowed young creators to loot soundsystem equipment from electronics stores. In 1979, the Sugarhill Gang, a group of rappers who only had peripheral connections to the South Bronx world, released "Rappers' Delight," the first rap song to become a pop hit. Eventually, a whole lot of other things happened, and hip-hop conquered the world.

The 50th anniversary of hip-hop is a slightly arbitrary milestone -- a bit like the idea of years themselves. It's a marketing opportunity. You can buy Sprite cans that are designed to honor 50 years of hip-hop. Lots of old greats built tours out of the occasion. Tonight in the Bronx, a vast array of rap legends -- Run-DMC, Ice Cube, Snoop Dogg, Nas, Lil Wayne -- will perform at a massive Yankee Stadium concert that's intended to mark the big anniversary. DJ Kool Herc and Cindy Campbell will be on hand. I just published the biggest freelance story of my life, a long profile of Too Short, in a New York Times Magazine special issue pegged to that 50th anniversary. People, myself included, are using this anniversary to make money. That's perfectly in keeping with hip-hop history, too.

Does the 50th anniversary mean anything other than a marketing opportunity and media circus? I truly have no idea. But the story of rap itself -- a form of art that was built from bits and pieces of what was available and that became the lingua franca of global popular culture -- is a beautiful thing. If this anniversary gives us a moment to reflect on that beauty, then it's worth something.