- Warp

- 2013

I wish I could say that I loved Daniel Lopatin's 2013 masterpiece R Plus Seven the first time I heard it. But, in all sincerity, it's an album that scared the absolute shit out of me for many years. As a teenager, I religiously watched Animal Collective live videos on YouTube. This habit tapped me into an algorithm of popular 2010s hypnagogic experimentalists like Battles, Gang Gang Dance, and, of course, Oneohtrix Point Never. While a lot of those artists went over my head at that young age, I was usually able to at least mesh with their colorful psychedelia. Yet whenever I would press play on R Plus Seven, I felt like I was doing something illicit; the cyber-dystopian album evoked hacking into some cryptic, ugly website loaded with government secrets.

Raised in the Boston suburbs, Lopatin's musician parents nourished his creative side. Access to his father's gritty cassette collection and Roland Juno-60 synthesizer allowed him to start exploring an interest in electronic music as an adolescent. Lopatin went off to school at Hampshire College but eventually transferred to Pratt Institute. Although he studied Archival Science there, life in Brooklyn thrust him into a circle of forward-thinking DIY artists. He started making music in the duo Games — alongside high school friend Joel Ford — which put an ambitious spin on the clunky tropes of vaporwave. (Ford, an impressive artist in his own right, went on to produce albums from artists including How To Dress Well, Jacques Greene, and Autre Ne Veut.) Lopatin also released work as Infinity Window and Astronaut, before ultimately settling on the moniker Oneohtrix Point Never (commonly abbreviated as OPN).

Early OPN albums were hazy and bleak, presenting a moody contrast to Games' '80s-inspired pop. Records like Betrayed In The Octagon and the Rifts compilation beg to score afternoons killed at bland office parks — meditative sounds for the screen-lit slog of day-to-day American existence. An immediate critical darling, Lopatin was already receiving comparisons to Tim Hecker and Emeralds when he put out his fourth album, Returnal, in 2010. After he launched the label Software and released Replica in 2011, he firmly cemented his place as an off-putting outlier in a musical landscape dotted with carefree chillwave and indie rock bands.

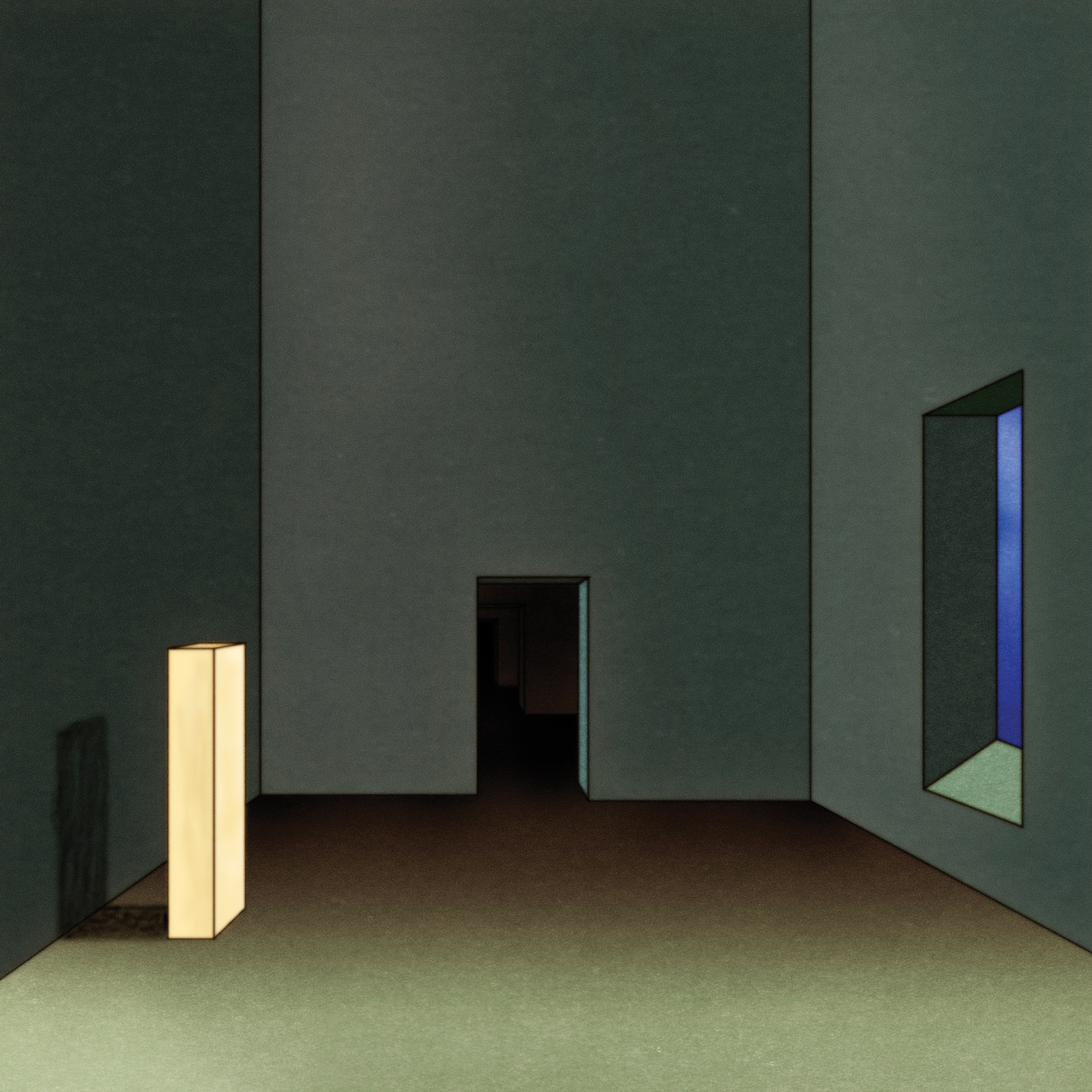

Lopatin soared to new heights with R Plus Seven, released 10 years ago this Saturday. His prior releases, while certainly great, played a bit like the output of a 20-something provocateur making weird noises on the computer. His Warp Records debut feels more like the work of a conductor leading an orchestra of VSTs and keyboards. Based on the aesthetics of its oft-memed, Georges Schwizgebel-indebted cover, many might be inclined to pigeonhole R Plus Seven as a relic of early vaporwave. But it actually has more in common with 20th Century minimalism and German ambient from the '90s, thanks to a tracklist that traverses cathartic peaks and desolate valleys. At some points, listening to R Plus Seven is a full-body experience; at others, things are so quiet that I've had to check to make sure the volume on my speaker hasn't been turned all the way down. There was a metallic quality to the OPN material that came before R Plus Seven, as if it was crafted from a sheet of stainless steel. On Lopatin's sixth album, it sounds like he's taking a sonic buzzsaw to that same silvery material, capturing the essence of the sparks it kicks up.

R Plus Seven eases in with meditative organ chords on "Boring Angel," before thick arpeggiations and melodic vocal chops emerge just past the 90-second mark. It slowly builds to an epic climax that sounds like what might happen if Black Dice covered Terry Riley's A Rainbow In Curved Air. "Americans" chaotically shifts between curt samples and peaceful, mallet-like flourishes. "Zebra" kicks off with a chorus of warbled voices, which gradually disintegrate into a foggy outro. "He She" is one of the glitchiest songs in Lopatin's entire catalog, centered on pitched vowels and the strange, distant twang of what could pass for a banjo. "Still Life" and "Inside World" are the most ethereal tracks on R Plus Seven, bathing chintzy, New Age textures in a fluorescent hue.

It all leads up to the stunning "Chrome Country," which opens with a cloud of analog chords. Robotic choir and piano motifs eventually emerge from the ether, growing sharper and more dissonant until they give way to a droning bed of strings and church organ. By the time it's fading out, the composition has wandered into unpredictable, borderline-neoclassical terrain — more similar to the sound of Philip Glass than Tangerine Dream. Looking back a decade later, I don't think it's unfair to call R Plus Seven’s closer one of the greatest electronic tracks ever made. It marries overwhelming digitalism and human emotion in a captivating, singular way. I can't help but put it on whenever I'm walking through the downtown of some unfamiliar city, staring up in disoriented awe at the buildings looming overhead.

Like the OPN albums that preceded it, R Plus Seven was met with widespread acclaim. Pitchfork gave it a powerful Best New Music designation. In the review, Editor-in-Chief Mark Richardson praised Lopatin's ability to explore new ground while retaining his established artistic fingerprint. In a review for NPR Music, veteran electronic journalist Ruth Saxelby called it "Lopatin's most colorful record to date, almost delightful at points, as well as delighted with itself." Even mainstream-oriented Rolling Stone chimed in, describing the album as "holy music, even if wholly weird." (In an interview surrounding the record, Lopatin fittingly told Stereogum that he was interested in exploring tension between religious and non-religious timbres while making R Plus Seven.) It may have left my spine tingling when it came out, but R Plus Seven quickly proved to be the rare avant-garde record that commercial publications could get behind.

R Plus Seven clicked with me over the course of a strange Orange County winter, when I was a college sophomore. I had just declared a Film Music minor. This had me taking a course on synthesis, where our professor encouraged us to show up stoned on the day our soundscape homework was due. It also coincided with a period of unwanted change, after many of my best friends had either abruptly decided to drop out or transfer. As I balanced my austere angst and rabid newfound excitement about LFOs, I found myself genuinely vibing with academic-sounding music. I spent most of my free time — and, frankly, a few hours that I was supposed to be in class — loitering outside of the warehouses and strip malls that dot Southern California, challenging soundscapes singing the cans of my headphones the whole time. It's not that some hidden beauty had randomly decided to reveal itself to me — I was just finally able to appreciate the ways in which albums like R Plus Seven made me cinematically terrified.

Lopatin has long been influenced by arty films, and R Plus Seven came out shortly after he and Brian Reitzell soundtracked Sofia Coppola's cult-favorite 2013 film The Bling Ring. "I was always screwing around with music, but I really wanted to go to film school when I was in high school. I guess what happened was that I didn't get into Tisch, that's what happened. I got deferred. And I went to Hampshire and ended up making music like everybody else there," he told Pitchfork in a 2010 interview. "I don't think I could make a good film, but I could definitely score a good film."

It's appropriate that Lopatin's true breakout moment came after he soundtracked the Safdie brothers' films Good Time and Uncut Gems. The A24 cosign thrust him into an even brighter spotlight, transforming Lopatin into an unlikely C-list celebrity. Through his work on Uncut Gems, he caught the ear of debauched popstar Abel Tesfaye aka the Weeknd. Their partnership that ensued opened even wider doors for Lopatin. He wrote three tracks for 2020's After Hours and 13 of the cuts on 2022's Dawn FM. He also acted as the musical director for the Weeknd's 2021 Super Bowl halftime show. All of a sudden, Lopatin was pulling the strings behind Billboard-charting records and major television events — an unusual career pivot for a guy who came up putting out noise collages with titles like "Child Soldier" and "Woe Is The Transgression II."

One might expect the quality of Lopatin's music to have taken a hit in the wake of his stardom. Against all odds, though, he's managed to stay fairly true to his signature sci-fi formula. For evidence, look no further than this 2020 Fallon performance of Magic Oneohtrix Point Never single "I Don't Love Me Anymore." Backed by a band that includes left-field percussionist Eli Keszler, Lopatin performs the guitar-driven track in front of a kaleidoscopic, cavernous backdrop. It's one of the most bizarre late night television nuggets I've ever encountered — an extension of Lopatin's freaky, baffling roots, broadcast on one of the most prominent stages available to a musician today. The moment was evidence of how far Lopatin has risen since R Plus Seven; like Brian Eno and Aphex Twin before him, he's the rare ambient musician who has been able to transform into an actual celebrity.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!