While the internet perverts our sense of nostalgia on an hourly basis, Daniel Clowes has already done so in print for 30-odd years. The artist has devoted his life to tapping into the subconscious of mass consumerism, filling his books with brightly-colored mascots, haunted humans, and weird sex.

The infinite charm to these worlds often lies in the background details, the most overlooked of which is the music. The author sneaks in ditties about Satan over a road trip that ends in the back of a cop car. The Ramones become the street gang for a teenager as she isolates in her room. Sinatra lyrics belch out in a bittersweet ode to Chicago. The new graphic novel Monica, hitting shelves this week, drops references to the Cure and Steve Miller Band. Every song that pings a little part of our memories elevates a Dan Clowes story beyond the panels.

I caught up with Clowes on Monica’s release day to talk about '70s butt rock, obscure R&B darlings, and the boomerang effect of the Kinks.

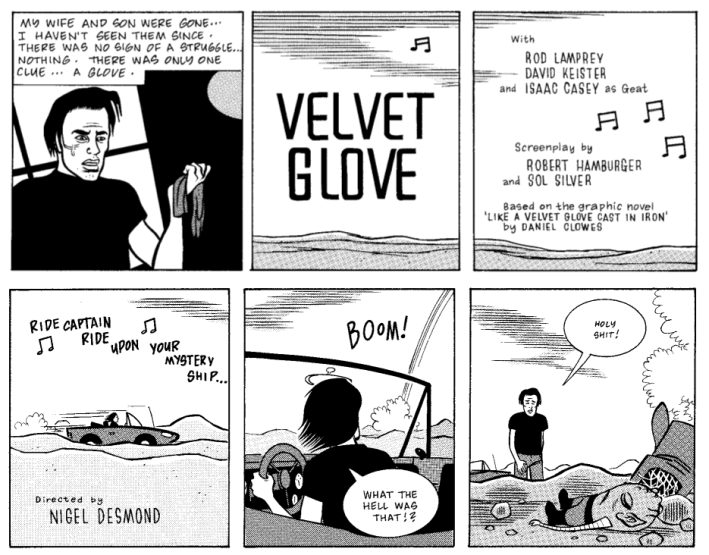

"Ride Captain Ride," Like A Velvet Glove Cast In Iron

Like A Velvet Glove Cast In Iron takes a man through an urban dreamscape of cults and snuff films in search of his estranged wife. The Eightball comic weaves in the gothic folk classic "The Ballad Of Barbara Allen" as a thematic backdrop, dark and dour and lovely.

To shake things up, Clowes created an epilogue that works as meta commentary on lame Hollywood film adaptations. The chapter follows an artist getting wooed by a scumbag producer who mangles the story into an action flop, complete with a butchered title, himbo leading man, and cornball soundtrack. "Somehow, [Blues Image's] 'Ride Captain Ride,' among me and my friends, became the perfect terrible song that was happily forgotten that would have been resurrected for a terrible '80s movie," the author grins. "To this day, that song makes me laugh every time I hear it. It's got such bluster to it that is absolutely unfulfilled by the music."

This is just one in a series of instances in which Clowes marries classic guitar rock with douchebaggery. Issue 13 of Eightball slanders a "disgusting idiot" roommate named Nat who "listened to Kansas."

Clowes elaborates, "When I was in college, Kansas would have been the indicator of somebody you didn't want to hang out with. If somebody was like, 'Yeah, I'm really into Kansas,' you'd be like, 'Next. Moving on.' [laughs]. By the early '70s, all of the guitar solos and the preening with everything turning into a big stadium spectacle with this kind of Dionysian front man strutting around was alienating and not in any way fulfilling to me."

This disdain is fully realized in Ghost World, the 2001 film version of his graphic novel. The main characters go to a bar expecting a night of homespun Delta blues only to be terrorized by the white bro stylings of Blues Hammer:

"Dew Drop Inn," Lloyd Llewellynn

When Howlin' Thurston the Third shows up in Lloyd Llewellyn, cool shit happens. He's tutoring teens in Tigertown! Space punks from Jupiter crash his shows! When asked about the inspiration for the rock god, Clowes smiles, "There was a Little-Richard-like singer called Esquerita who had this giant tower of hair and these wonderful round sunglasses. He had the look of an unapproachably cool character."

Steeped in wonky, martini-drenched neo-noir, the world of Lloyd Llewellyn was a welcome escape from the hair metal and forgettable comics that dominated the late '80s. Although Clowes was publishing in strictly black and white, the gyrations and furious antics of the Howlin' Thurston still manage to leap from the pages.

Clowes muses on digging too deep in the days before the internet, "I was operating under the assumption that anybody had any idea who I was referring to (laughs). My readers became the 20 people on the planet who knew who Esquerita was."

"Carbona Not Glue," Ghost World

Ghost World gives us entrée into the lives of Enid and Rebecca, talking constant shit about all things before the crush of adulthood takes hold. Enid has a deep dive punk day, which Clowes pulls from his own youth: "When I first heard Devo, that was the moment my life changed. All of a sudden I thought, 'Oh, I understand these guys. This is an aesthetic.' And that led to the Ramones." The author moved to New York in 1979, when there was still a vestige of the punk scene left that he got to experience firsthand.

Ghost World has the distinction of being the most overhyped piece of Clowes' catalog while also being his very best. From recurring leads down to the smallest goons, the characters clash like a patch of fragrant wildflowers on the edge of a parking lot.

"Stardust," Monica

Monica cuts a playfully jagged path through a woman's life story. The plot itself is steeped in echoes: of family, of memory, of the bubbles of pop culture that have long since burst, leaving dried rings on the surface of what remains.

We get a rare moment of this when young Monica discovers a beat-up AM radio that transmits a spiritual signal to her dead grandfather. They spend weeks together, at one point singing Stardust to each other in bed; it is a moment of displaced tenderness in that the closest she can get to real love comes from a little plastic box.

For Clowes, the mystic bonds of music and family are similar. One of his earliest memories involves his grandfather playing Leadbelly records on an old tube record player. When Clowes reached to turn off the machine, he accidentally grabbed a red hot glowing tube instead of the power switch. "I got a very severe burn on my hand. From then on, music felt very scary to me. It was somewhat associated with pain and trauma."

Scary childhood experiences aside, I still ask him if he has a favorite band.

"I mean, I find I go through phases. I go through my life and every five years I'll get obsessed with the Kinks," Clowes admits. "I just love them. Their songs are about cats and their sister and the village green as opposed to smoking dope and all that stuff. Ray Davies, especially, has a great sense of humor that I find endlessly inspirational."

After decades spent hunched over a drafting table, lost in vivid worlds and surrealist fantasies, I suggest that Clowes must listen to some wild music while he works. His answer is shockingly simple: nothing.

"When I'm writing or drawing, I can't have any sound or music. I have to hear my own thoughts and feel my own rhythm."

Monica is out now via Fantagraphics. Lee Keeler is a writer and educator living in Northeast Los Angeles.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!