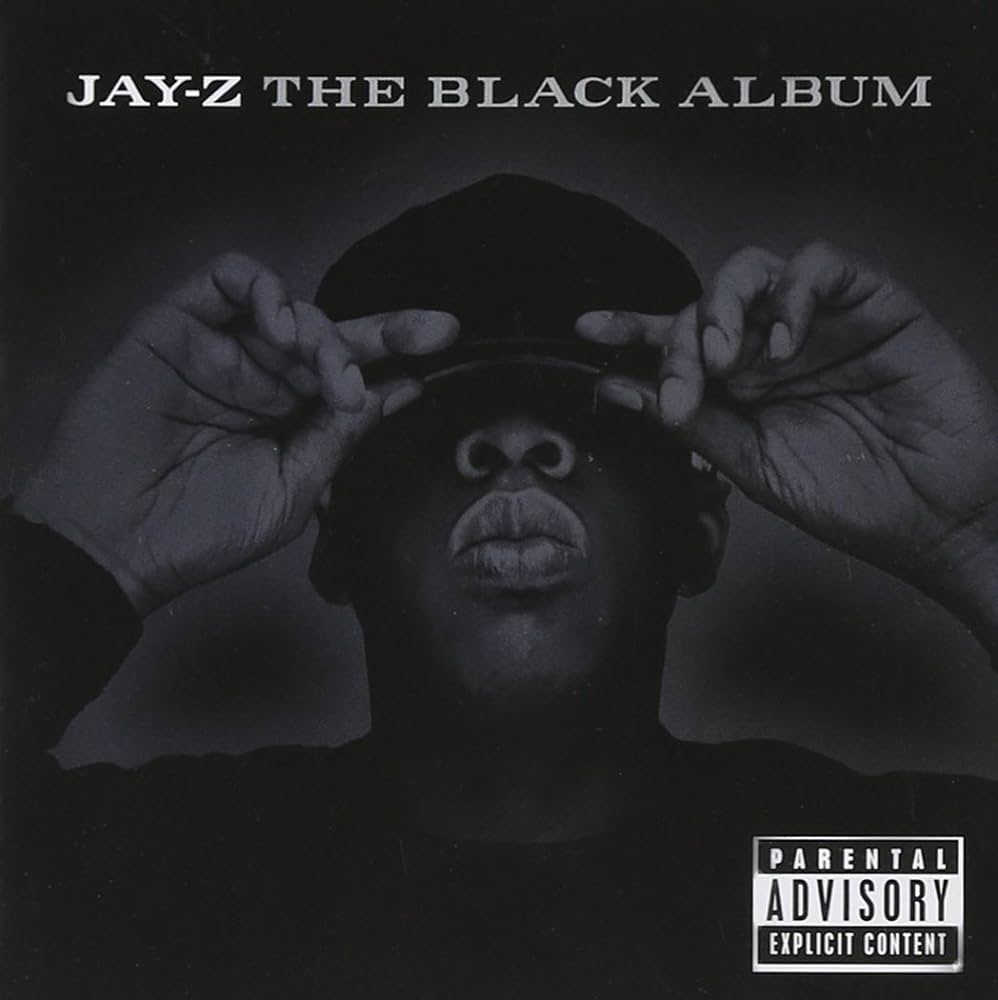

- Roc-A-Fella/Def Jam

- 2003

October 27, 2005. East Rutherford, New Jersey. The building then known as the American Airlines Arena. My first Jay-Z show. (I was pretty late. Can't believe I didn't see the Hard Knock Life tour.) It was deep into Jay's fake retirement -- two years after The Black Album, the fake-goodbye record that turns 20 today. In his fake retirement, Jay didn't really stop doing anything -- he didn't even stop touring -- but this was billed as a special evening. Jay had some things that he wanted to get off his chest. No opening act that night. Instead, the lights came up on a mocked-up Oval Office, with a presidential seal of the floor and Jay sitting behind a massive oak desk. While the crowd was still reacting to what it was seeing, six piano notes ran out -- the "PSA" intro. When the drums kicked in, giant jets of flame shot up from the floor. To this day, it's one of the coolest things I've ever seen.

Here's the thing, though: The first time I heard the drums drop on "PSA," I wasn't in that arena. I don't remember where I was. Maybe I'd just run home after beelining to the record store on release day, throwing the CD on as soon as I could reach a CD player. But I can tell you that jets of flame shot up inside my brain when those drums hit. When I hear "PSA" today, the same thing happens. "PSA" comes on, and I'm a barbarian on the battlefield, pulling my axe out of somebody's skull and howling at the sky. I'm a torpedo, crashing into the hull of a destroyer. I'm a piano, falling out of the sky and landing on Yosemite Sam's head. That track does something to me, and it always will.

"PSA" almost didn't happen. Just Blaze wasn't supposed to have multiple beats on The Black Album. Nobody was supposed to have multiple beats on The Black Album. At a certain point, The Black Album was supposed to be a full-length collaboration between two men, Jay-Z and DJ Premier. Then, later on, it was going to be 12 songs with 12 different producers -- Jay's wishlist of the best beatmakers in history. Jay even took out magazine ads for that one. The image was a cassette tape inlay card, with "Untitled" repeated 12 times and names of producers next to every track: Premier, Dr. Dre, Swizz Beatz, the Trackmasters. In the end, The Black Album was more of a patchwork than a masterplan coming together. Premier, Dre, Swizz, and the Trackmasters weren't on the record. A few total-unknown producers did appear, and the experience did not turn them into household names. "PSA" made it onto the album at the last minute, after Just Blaze made the track and then ran down the studio hallway to show it to Jay.

Jay-Z knew how to plan, and he knew how to change his plan on the fly. The Black Album was a grand cultural event right down to the Gladiator sample. Jay-Z started teasing his retirement almost from the moment that he arrived at stardom. It was part of his mythos. From Reasonable Doubt on, Jay rapped like nothing could possibly ever bother him. He was above it all. The story was that Jay had made so much drug money that music was simply an indolent hobby. He dabbled in crazy weight, without rap he was crazy straight, still spending money from '88, etc. In rap, confidence is everything, and nobody has ever sounded more confident than prime Jay-Z. When Jay called himself the best rapper alive, you believed it, because you knew that he believed it. The constant retirement-talk sent a message: You don't deserve me. You might take me for granted, but before you know it, I will be gone. And then he had to make good on it, at least for a little while.

The Black Album had expectations. Even if the tracklist didn't come together in quite the way that Jay had envisioned, he still got most of his all-time great wishlist producers. He recorded without a single guest-rapper. He spent whatever money he wanted to spend on sample clearances. Jay already had a massive career. Since 1996, he'd released an album every year. Since 1998, those albums had all been blockbusters. Jay had amassed maybe the greatest rap crew of all time around him. He'd founded a massively successful clothing line and opened an uptown sports bar. He'd become half of pop music's greatest power couple. He had hits on hits on hits. There were missteps -- the previously year's occasionally great but inarguably baggy double-CD The Blueprint 2: The Gift And The Curse, for one -- but his career was already legendary. He knew that. He knew it before anyone else.

Jay was always aware of his own legend status, and The Black Album was the moment that he made it literal. A week after the record's release, he made that status as literal as he could, throwing himself an all-star goodbye show at Madison Square Garden. As the evening began, Michael Buffer boomed out a royal introduction as a Jay-Z jersey sailed into the Garden's rafters. It was almost hilariously overblown, and that's why it was awesome. In that moment, everything that Jay did felt like some great feat of American grandeur.

But how does a mere album live up to all that showmanship and ballyhoo? How does it even hang together as an album? How do you avoid the noise drowning out the music? Easy. You make "PSA." You make "99 Problems" and "Dirt Off Your Shoulder" and "Lucifer." You rhyme "I put hands on you" with "I dig a hole in the desert, then build the Sands on you." You don't coast on past glories. Instead, you come up with some of the coldest lines of your entire career, and you organize and deliver them in ways that will get lodged in people's heads for decades. Individual sentence fragments from The Black Album will live in my heart forever. Grand opening, grand closing. Curse the day that birthed the bastard. Hustlers, we don't sleep, we rest one eye up. I check cheddar like a food inspector. Bounce on the devil, put the pedal to the floor. Screaming out the sunroof: "Death to y'all." Even the ad-libs -- "You crazy for this one, Rick!" -- take up entire stacks in the permanent collection of my mental library.

The Black Album opens with a crackly speech about all things coming to an end. (It sounds like an old recording, but it's really Just Blaze talking through a filter.) Then: A cascade of horns and choirs ring out from an old Chi-Lites record while Jay's mother talks about how she didn't feel pain during his birth. It's Jay tooting his own horn, and then he does that same thing again and again. "December 4th" is Jay pushing his legend harder than he'd ever pushed it, telling the origin story about the sycamore tree where his parents conceived him and Spanish José introducing him to 'caine. It should be numbing and overblown -- a wedding-toast PowerPoint slideshow set to a fireworks display. But it works. For the next hour, almost everything works.

There are things about The Black Album that never worked. "The Martha Stewart that's far from Jewish." The terrible fashion trends that sprang directly out of Jay stumping for jeans and button-ups. The two baffling soft-batch Neptunes tracks that I still skip whenever I play the album. There are other things that don't really work now. You can't be Che Guevera with bling on anymore. You can't explain that your own obscene personal wealth is a net positive for society. You can't talk about how you'd really like to be Talib Kweli if market forces didn't demand total pop stardom. (Kweli was never half as good as Jay in the first place, anyway.) You can't humblebrag about dumbing for your audience to double your dollars, since your audience might notice that and object.

But the bullshit never stuck. Jay was bigger than his own flaws. I never got bored listening to The Black Album. "Dirt Off Your Shoulder" came right after "Change Clothes," "99 Problems" after "Moment Of Clarity," "Lucifer" after "Justify My Thug." The album had valleys, but you could use those valleys to process some of the unbelievable shit that you'd just hear Jay talking about. "Let me tell you dudes what I do to protect this/ Shoot at you actors like movie directors." "The more you talk, the more you irking us/ The more you gon' need memorial services." "God forgive me for my brash delivery/ But I remember vividly what these streets did to me." "If you can't respect that, your whole perspective is wack/ Maybe you'll love me when I fade to black."

The creation of The Black Album was immortalized on film in Fade To Black, the concert movie about that Garden farewell. Along with some truly great live-show footage, we see Jay traveling around, taking pitches from some of the biggest producers in rap history. There are moments in the documentary that stick with me almost as much as anything that Jay says on the record. There's Memphis Bleek asking Q-Tip if he wants anything from Outback Steakhouse. There's Rick Rubin telling Mike D about how Jay never writes anything down, as Jay practices his racist-cop accent. There's Timbaland swigging from a gallon jug of purple juice, giggling to himself about the expression on Jay's face the first time that Jay hears the "Dirt Off Your Shoulder" beat. It all goes down in dingy studios and featureless conference rooms, and it's all so beautiful.

A few months ago, I interviewed Too Short, the inventor of the fake rap retirement, and I asked him about the thinking that led to his own 1996 goodbye record Gettin' It (Album Number Ten). Short told me that he was turning 30 -- ancient for a rapper back in those days -- and that album number 10 felt like a nice round-number moment: "It was my quarterback Super Bowl-winning season. I retire after I win the Super Bowl. It's that moment." Short also told me that everyone wanted to work with him once he said goodbye: "I did dozens of features after I announced my retirement. Everybody started offering me a lot of money to not retire." Three years later, Short came back with an album called Can't Stay Away. He hasn't stayed away since.

Jay was 33 when he recorded The Black Album, and he spent the next few years attempting to sink back into a record-executive role. Maybe Jay, like Too Short, thought he was getting too old to keep rapping. Months before Jay released The Black Album, 50 Cent emerged as a challenger to his New York rap throne. Jay and 50 toured together that summer, and rumors of tensions were all over the place. On The Black Album, Jay took a veiled shot at 50: "No I ain't get shot up a whole bunch of times, or make up shit in a whole bunch of lines." (Pity Busta Rhymes, who happened to catch a stray because his name fit the cadence.) This wasn't Jay's first time big-dogging 50 Cent, and 50 tried to respond. 50 moved up the release of the G-Unit group album Beg For Mercy so that it would come out on the same day as The Black Album. If 50 won that sales battle, it would be a true changing-of-the-guard moment. But it wasn't. Beg For Mercy sold 377,000 copies in its first week. The Black Album sold 463,000. The margin wasn't huge, but Jay still reigned.

After that, Jay couldn't leave rap alone, retirement be damned. Within a year, he had collaborative albums with R. Kelly and Linkin Park on the market. Three years later, Jay was back with the absolute piece of shit Kingdom Come, and all pretenses at retirement came to an end. It didn't matter. Jay had already built a monument to himself. Everything that came afterward existed in its shadow. Jay has made good records and bad ones after The Black Album. He's seemed unbelievably cool, and he's seemed like the corniest man on earth. (He's closer to the latter now; the world did not need him to turn the central branch of the Brooklyn Public Library into his own personal Colossus of Rhodes.) The image of Jay shot to death at the end of the dazzling "99 Problems" video is still the one that lingers in my head -- almost as if Jay really had died on that sidewalk.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=Rl2I8QjBVRc&ab_channel=Enjoyit%F0%9F%A4%8D

Context matters. When The Black Album came out, Jay-Z was the coolest person on the planet. In the months that followed, younger rappers started making hit songs out of sampled fragments of stuff that Jay said on the record -- T.I.'s "Bring Em Out," Cassidy's "I'm A Hustla." Moments from The Black Album have their own out-of-time resonance -- a mustached and mulleted Colin Farrell, for instance, tracking a pimp across a nightclub dancefloor while the Linkin Park version of "Encore" booms over the speakers in the opening scene of Michael Mann's Miami Vice movie. Danger Mouse built a career from a gimmicky viral mixtape of Black Album remixes. Jay started playing radio-station alt-rock festivals and performing "99 Problems" with Phish and shit. Three months later, Jay's protege Kanye West released his own era-defining debut, and then that record defeated The Black Album to win the Best Rap Album Grammy.

I wonder how The Black Album sounds to people who weren't on board for the moment 20 years ago, who didn't rush home from the record store to rip the plastic from their CDs. Maybe you had to be there. Maybe a young person could listen to the record now and hear a self-justifying billionaire trying to make a case for his own coolness. Personally, I don't care. The Black Album was a moment, and some moments never fade. Sometimes, you can look back on those moments decades later, and you can still feel the jets of flame.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!