It's a Saturday afternoon in late October in New York City, and the Grammy winning jazz pianist, producer, writer, and arranger Robert Glasper has a problem that has plagued bandleaders for generations: With little notice, a crucial piece of his ensemble has bailed on an upcoming gig, and he now needs to find a fill-in on the fly.

The band member is the Bed Stuy-born rapper Yasiin Bey, formerly known as Mos Def, one of the founding fathers of the backpack era of conscious rap in the late '90s, for whom Glasper has served as an off and on music director since 2005. Glasper knew something was up because he'd been playing phone tag with the rapper all week, and Bey never uses the phone. He didn't even own one until three years ago when he got an iPad, which he still only uses sparingly, so when Bey is calling, you know it's urgent business.

Yasiin expatriated years ago due to enmity he has towards his country of origin. He was calling Glasper from his home in Barcelona to apologize, explaining that with everything going on in the world — referring to the current genocide/ethnic cleansing being carried out with American complicity in Gaza — he wouldn't be making it to America. "As we say, Mos be Mos-in," Glasper said, conjugating the rapper's moniker to verb and punctuating it with the mock-exasperated, good natured laugh you might have explaining an old friend you love but can count on occasionally flaking.

The "gig" is 10 sets, two shows a night over five nights. It's part of Robtober, Glasper's annual month-long residency at the Blue Note, the venerated 42-year-old jazz venue on MacDougal Street in the still dingy heart of the West Village. Glasper explains, "My goal was to get some people that I've already rocked with, that I know will be cool with doing two sets a night. And they're already family. So it's like, 'Hey, I'm in a bind. Can you bail me out?'"

His first call was to Wasalu Jaco, or Lupe Fiasco, whose working relationship with Glasper dates back to the first installment of his groundbreaking Black Radio series in 2012 (or as Lupe puts it, "I can't really remember but def a long ass time ago"). The Chicago native is currently living in Cambridge, serving as a visiting professor and scholar teaching courses in subjects like "Rap Theory & Practice" at MIT. He said he'd drive down, but could only cover the Tuesday/Wednesday sets.

That left Friday, Saturday, and Sunday, so Glasper called an old friend, Tariq Trotter, or Black Thought, who he knew would be in town because he serves as the frontman for Philadelphia's Roots Crew, the house band for The Tonight Show. Glasper and the Roots have a deep, lasting, symbiotic relationship, and Thought immediately stepped up for the weekend. So miraculously, in the span of an hour or two, Robert Glasper had traded one rap legend for two. The ease with which he pulled this off, the global network of talent he now has at his fingertips — all of whom have come up from humble beginnings alongside him to reach impossible heights of accomplishment — is a testament to the institution his Blue Note residency has become.

Robert Glasper was born in Houston in 1978 and came to New York to study at the New School in the late '90s. He was mentored by the Roots and J Dilla, but in his ushering of jazz into a new age of radical pop experimentation, his spiritual forefather is his GOAT, Herbie Hancock. Over a 25-year career he's collaborated with Kendrick Lamar, Brandy, Nicholas Britell, Common, Kamasi Washington, Chaka Khan, Snoop Dogg, Rakim, Killer Mike, Norah Jones, Maxwell, Terrace Martin, Ty Dolla Sign, Jill Scott, and his onetime roommate Bilal among many, many others. He's currently a member in approximately 13 bands. Two of his three transgressive Black Radio installments have won Grammys by melding the entire history of Black music into one smooth and cohesive expression. And for the past five years, every October he's continued to push that project forward with Robtober, a funky and wildly unpredictable jazz/rap/R&B laboratory that remains one of the hottest tickets in New York, which attracts onlookers like Mary J. Blige and Scarlett Johansson and unannounced performers such as Kamasi Washington, Q-Tip, and Dave Chappelle.

The Blue Note might surprise a visitor who only knows it from myth, legend, and live recordings. It's on a block branching off what could be thought of as a downtown Times Square, bisecting the IFC Center, and The Cage off the West 4th subway hub, and the crush of NYU-student-friendly takeout eateries and bars on the narrow, off grid, one way streets around the university and Washington Square Park. The club is tucked into the middle of one of these streets, and if it wasn't for its distinct marquee, curved like the tail of a grand piano, with the Blue Note's name embossed in gold lettering, you could miss it. Inside is just as surprising: low ceilinged and cramped, somehow a 200-seater with long, thin tables pressed together, creating tight angles for servers to navigate and little legroom for guests who'd better be comfortable making new friends. Each table is embedded with a sunken gold emblem that features the names and signatures of legendary artists that have played the club etched into it, like a Hollywood Walk of Fame, or a synagogue.

The Blue Note opened in 1981. It hasn't been renovated in years, and it shows, even beyond the two neon signs — one above the bar and one on the club's far wall — that both depict Manhattan's skyline with the Twin Towers standing shoulder to shoulder. The club is charmingly "preserved" in a way most city proprietors won't allow their spaces to be anymore. The walls are layered with slats of mirror and black padded vinyl; the black carpet, featuring a repeating geometric Trapper Keeper pattern, is well-worn; the entrance area around the bar is lined with wood paneling and black marble tiling. If you didn't know any better, you might confuse the Blue Note for an event space suited for '90s quinceañeras or amateur-friendly open mics, rather than arguably the most storied landmark music venue in New York south of the Apollo and Radio City.

Glasper's relationship with Blue Note goes back decades. Over time, it has become a true partnership, more than the typical impersonal transaction between a musician and a performance space. In addition to Robtober, in the last two years he began programming the Blue Note Jazz festival in Napa. It's a dream come true for Glasper, who as a child, would listen to his favorite album, Oscar Peterson's Live At The Blue Note. When he came to New York, as a young student, he had a gig playing organ at the Canaan Baptist Church in Harlem on 116th, and would save the little money he made to go see his heroes, like Chick Corea, at the venue. When Glasper started playing the Blue Note, he brought a sound the club had never seen before, bringing unconventional talent that brooked with the traditional roster and style of play. It quickly found an audience.

Of how the relationship evolved over time, Glasper says, "I was pretty much doing Robtober, just not for a month. So I would always have an R&B artist or a hip-hop artist that had never played there before, and we would do two shows. And then those two days turned into, 'Oh, let's try five days.' And then the five days turned into a week. At one point, I did two weeks. And I rocked it, it was sold out. So that's when someone said, 'Do you want to try a month?' And I was like, 'The fuck? That's crazy. How does anybody do a month anywhere?' But I said why not, we mapped it out, did the first one, and I was like, 'Oh, shit, it can be done.'"

Speaking to the happy byproduct of the security and the freedom the residency provides, he continues, "Blue Note has become a hub for me. It's like a playground, and we know it's going to be sold out no matter what I do. Like, last year, we didn't even put the guest on the flier when we first announced Robtober was happening, and 75% of it got sold out in the first week." Alex Kurland, the longtime talent booker of the Blue Note, explains their relationship, and what draws artists and crowds into the residency with a reverence that borders on quasi-religious idolatry:

It's hard to measure this, but I think it's just his vibe. He has this unbelievable vibe, and it's very inspiring. It's very open, it's very free. And I feel like Robert's greatest quality is how giving he is as an artist and how inspiring he is as an artist for other artists. When you're in the room with Robert Glasper, when you're breathing the same air as Robert Glasper, you feel amazing. And I say that as a fan, he just has this superpower that transcends even just his playing. It's just how he makes you feel. It's how he makes the fans feel. It's how he enables his artists around him.

The author, music historian, and Tisch professor Dan Charnas, who featured Glasper prominently in 2022's seminal Dilla Time, has a similar, if not slightly more measured take on how Glasper's shows have become a kind of summer porchlight for disparate talents: "I get it more from when he's on stage. He has a really great sense of play. I don't mean playing like playing a piano. I mean… he plays, he's having fun. He loves music. He loves people. He's funny. It's not like, 'Oh, I'm doing serious music,' even though it is very serious music, but it's fun for him, and you get that sense of fun. And so people want to be around that, and people want to play with him when he's playing."

https://youtube.com/watch?v=cxbqdI4gtZg

I was fortunate to be in attendance for one of Glasper's shows — the late show on Friday night, Nov. 3, featuring Black Thought. I don't mean that in the typical fawning journalist sense, as in, what a privilege it was to be in the presence of greatness, although that's also true. What I mean is I was fortunate to simply make it through the door, as it was a mob scene, people in an unruly line stretching down the block were demanding they were on one list or another, waving their tickets and shouting at the door, that had to be closed and locked as the venue attempted to seat a throng of guests and bring temporary order to abject chaos. To quote Thom Yorke, as Glasper once did, it was packt like sardines in a crushd tin box. I overheard a manager and a guard working the door debating whether one large party of well dressed young men were part of Rakim or Maxwell's crews. Hardly the type of demand one might expect in 2023 for one of 50 ostensible jazz performances crammed into a single month.

This is because to refer to Glasper's residency as purely jazz is misleading. The show I watched that Friday night was somewhat bifurcated. It began with a half hour of instrumental jilted rhythms with Glasper's band, composed of lifetime friend and drummer Chris Dave, bassist Derrick Hodge, and guitarist Isaiah Sharkey. Glasper opened with a display of technical mastery, playing a keyboard with each hand, in complete and total discordant harmony that would clash then resolve. It sounded like two different musicians were each playing both instruments separately with two hands. The band then laid down a laconic, digression rich dreamscape that sonically landed somewhere between Terrence Blanchard and Bruce Hornsby and generously granted each member of the crew ample solo time to cook. The band quoted phrases and melodies from jazz and rap history; the DJ scratched in whispers of verse and tags that had the effect of trying to listen to Hot 97 just beyond the radius of its terrestrial signal. Charnas describes their reference-laden performance style as "a very postmodern way of looking at improvisation, meaning that it's almost like listening to somebody sampling themselves, in a way."

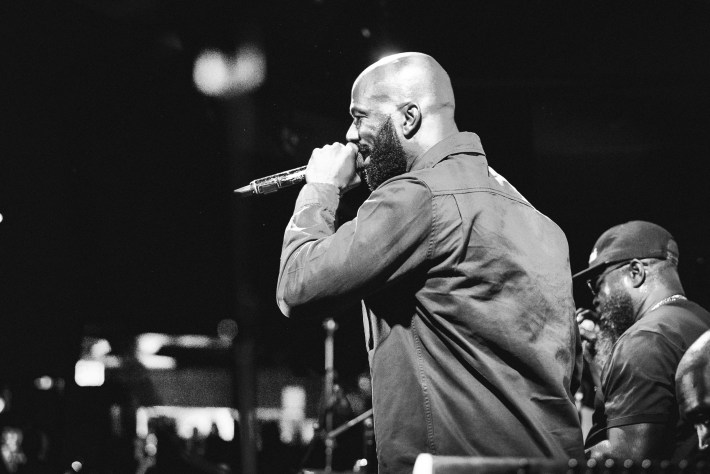

Then for the second half, Black Thought came out spitting gutbucket hellfire over a Dilla interpolation, spending 45 virtuosic minutes now firmly in his Louis Armstrong, biblical salt-and-pepper-bearded old master era. It wasn't a "Black Thought Set." There were no proper songs. The band would establish a base rhythm, and Thought would answer with snippets of verse, some his own, some not. One minute he's freestyling acapella, the next he's doing a verbatim rendition of "Liquid Swords" over a beat that in no way resembled the source material. (As Glasper told me, when he reached out in an attempt to plan out something like a song list with Trotter, "I was like, any specific songs you want to do? He said, 'Man it don't matter, I'ma rap for 45 minutes. Switch it up under me and I'm going to just go with it.' And I was like, bet.")

It was all unrehearsed, built off spontaneous collaboration, reaction, and improvisation. It was less a "concert" than a highly skilled but unstructured, fluid conversation held between musicians and vocalists, between generations of Black artistry and genres therewithin, an insane freewheeling survey of jazz and rap simultaneously, arbitrarily plucking legends and melodies decades — if not centuries — apart, mixing it all in a paint bucket and splashing cosmic slop across a spinning canvas, somehow producing a smooth postmodern product that contains everything and sounds entirely original. It's perhaps the most realized and crystallized praxis of the Soulquarians' diverse, over-educated, Black music history quizkid pastiche.

I asked Charnas if he could help me define what Glasper is actually doing with his music and performances, if he could help me make sense of what I'd seen: "Well, look, there's lots of debate about the validity of genre in the first place. And I think one of the things that Robert Glasper has been trying to do is to not be pigeonholed in genre, and have lots of different descriptions and crossovers. If I were to expound on that, it would almost be antithetical to what Robert Glasper's mission really is, which is to break down genre. That said, I think that just like all American music, his home base is jazz and blues. That's whence he comes. But his importance for me is that he is one of this particular generation, maybe the first to really have grown up on hip-hop, and to see the commonalities that great hip-hop musicianship and jazz share."

The conversation I saw being conducted on the stage at Blue Note, that style of performance and its seamless blending of traditions, doesn't begin with Glasper. It may not even begin with the Roots, but for Glasper, it began with them, at a club called the Black Lily in Philadelphia. As college students, Glasper and Bilal would take a Greyhound bus from New York to Philly for the performances, not necessarily to play, just to soak in the vibes. "It was a place where they would have these jam sessions. And that's where the sound of neo-soul came from. That's where the Jill Scotts and the Musiq Soulchilds came from, that Philly sound. The Roots were cutting their teeth there at that club, that's where everything started. I saw Jazmine Sullivan there when she was still a teenager. It was like the breeding ground for so many artists." These jams migrated over the years, from Philly to New York at Wetlands, where Glasper really got to know the group and began sitting in with them. For a while, he became a de facto member, even receiving an invitation to join them when they took the Fallon gig in 2007.

From there, Glasper began proselytizing, taking the gospel he found at the Black Lily and making it his own with jam sessions he'd host, most notably, at the Up Over Jazz Cafe (between 2000-2004) on Flatbush, above a Wing Wagon, in an unlicensed club with no liquor license. Glasper reminisces, "They couldn't pay me nothing, really, because there was barely anybody. I wasn't bringing in a big crowd or anything, and I was young, so they were like, hey, you can do whatever. So it was just me and my trio, some stragglers coming in and out, a bartender and a waitress. It was a place for us to practice, work out our sound. Then on Thursdays, they gave me a hip hop jazz night. So we would have microphones on stage. And if you'd come up to sing, you couldn't suggest a song. You had to literally go with whatever the vibe was and just jump in. And if you're a rapper or a poet or a singer or a musician, it's the same thing. There were no songs allowed. It was only vibes." It's a history he's honored with Robtober, with legends and celebrities taking the place of random, courageous Prospect Heights artists who would drift in.

On how Glasper has honored that tradition and moved forward with it, both on wax with Black Radio, and at the Blue Note, Charnas says, "It's Robert Glasper, in many ways, who confirmed a lot of the notions of the Soulquarians, that there's this place beyond giving music completely over to the machine, that there's this place beyond the fetishing of synthesis and the fetishingof the relentless new. I think, certainly, because D'Angelo hasn't had much of an output, Glasper is the one who's really carrying that concept forward. But he doesn't just play. He curates. I think what's really important about the Blue Note residency is that Glasper is taking an active role in curating what jazz is going to be in terms of popular music."

Alex Kurland believes the brilliance of Robtober goes beyond performance, that the loose framing of the month, the allowance for sudden, improvised programming of the residency speaks to the nature of jazz itself, stating, "Glasper is completely unique and original with how he facilitates the residency and how we present it at the Blue Note. We're trying to open up these moments that are spontaneous. There's the openness, the freedom, the spontaneous improvised experiences that are often a result of collaborations or of moments that occur based on artists coming together..It transcends genre. It creates an open space for music to have its freedom. That's why the residency is drawing in culture-bearers from the standpoint of comedy, from the standpoint of film and television, even in the athletic world, he just draws in champions, great individuals that transcend just music."

Glasper has taken the freewheeling nature of his jam sessions and organized them, making every October a tour inside his consciousness, a leafing through his scrapbook, or a spin through the streaming app on his phone. It's an homage to the legends that inspired him, and the artists, friends and collaborators that he's picked up on his journey. So here's a three-day, six-set tribute to Roy Hargrove, who took Glasper on his first tour as a college sophomore, or Mulgrew Miller, or Wayne Shorter, or Art Blakey, bookended by "fusion" nights with one or two Wu-Tang Clan members, with a surprise appearance from a neo-soul legend like Jill Scott, and maybe Chris Rock will pop in to shoot the shit and fire off a few jokes while waxing rhapsodic on Glasper's brilliance.

Glasper's Black Radio series, as well as 2019's Fuck Yo Feelings, can be understood as an attempt to consecrate the in-the-room, anything-is-possible spontaneity of his Blue Note performances, committing the texture and unpredictability of life to wax. Each project has its highlights — and, as critics like to point out, moments that could've been left out — but this is the point of experimentation and leaving it all in. Glasper's output should be considered less by the album, and more as a life's work broadening the borders of hip-hop, jazz, R&B, the blues, funk, indie rock, and wherever else his curiosity guides him. Charnas adds, "What he's doing is super important. Something new is being born and that he has a lot to do with. The Beatles may have been the first to create popular music out of collage, out of sonic collage. But it took hip-hop producers and DJs to make it real, to fulfill the promise. In the same way, Dilla pointed to a new way of relating to time. But it's Glasper, in many ways, who has taken that mantle forward. There's a reason that the narrative of Dilla Time ends on that Blue Note stage with Glasper and T3. There's a reason."

Robtober remains one in a rapidly diminishing number of events New Yorkers use to continue thinking of themselves as God's Chosen People in Mecca. Even now, in Eric Adams' washed city of real estate developers and six-figure, members-only social clubs, we can say here, in the West Village, every autumn, we get access to a kind of sprawling, nightly jazz festival/historical preservation society meeting/time machine that moves both backwards and forwards you won't find anywhere else on Earth. Robtober is a one of a kind cultural institution, a living museum, a gymnasium for the most talented artists on Earth.

For the late show on Sunday night, Nov. 5, to close out this year's festivities, Black Thought was joined, unannounced, by the RZA, Common, H.E.R., and of course, Flavor Flav. I asked Glasper how the fuck that random collection of incredible talent was assembled. As is par for the course, he told me, "When I woke up Sunday morning, I had no idea any of this was going to happen. I didn't know Flavor Flav was going to be there, my dentist actually brought him. He hit me and was like, 'Yo, I'm rolling through. Can you put me on a list?' at like, 6 o'clock, FaceTimed me with Flav from the dentist office because he does Flav's teeth. Flavor plays piano, too. So me and him talk about piano shit. But anyways, that's how the day unfolds sometimes with this shit man. Any given night, something can pop off."

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!