- Record Collection

- 2004

"The Rat" is a masterpiece. Everyone knows that.

Not many indie rock songs — or rock songs, or songs, period — have ever captured the explosive feral energy the Walkmen harnessed on their signature song. Paul Maroon hits those distorted guitar chords so fast that they almost blur into Walter Martin's organ drone, creating a sound so beautifully violent it sends a tingle down my spine. Matt Barrick bombards his drums as if engaged in competition with Maroon to see who can strike their instrument harder. When Peter Bauer's bass kicks in, the whole thing coalesces into a tidal wave of melodic noise, barreling forward without heed for tact or safety — and that's before Hamilton Leithauser jumps on the mic with one of his most ferocious performances, angrily screech-wailing about broken relationships of many kinds, via lyrics so powerfully concise they almost overshadow the glorious racket.

There are very few words in "The Rat," and Leithauser makes every line count, both as a writer and a singer. The strangulated-Dylan intensity he brings to every "you've got a nerve" and "can't you hear me" is a superpower reserved for an elite class of peculiar rock ‘n' roll vocalists. The one time he quiets down, it's even more memorable. ("When I used to go out I would know everyone that I saw/ Now I go out alone if I go out at all": that's a bar.) With one heaving four-minute eruption, the Walkmen preceded peers TV On The Radio's "Wolf Like Me" on the "indie songs for driving dangerously fast" Mount Rushmore and beat kindred spirits the National's "Mistaken For Strangers" into the "elegantly rumpled New York suit-and-tie guys lamenting their social alienation" hall of fame.

This is a song that clenches my muscles, pauses my breath, raises my blood pressure, and, yes, really makes me think. It both slaps and rips. It is, without hyperbole, an actual work of genius. It deserves to be described with fanatical enthusiasm, at excruciating length, before ever mentioning anything else its creators ever did. All that is true about "The Rat" and is accepted as gospel by most in the orbit of 2004 indie rock. And yet Bows + Arrows would still be basically a perfect album without it.

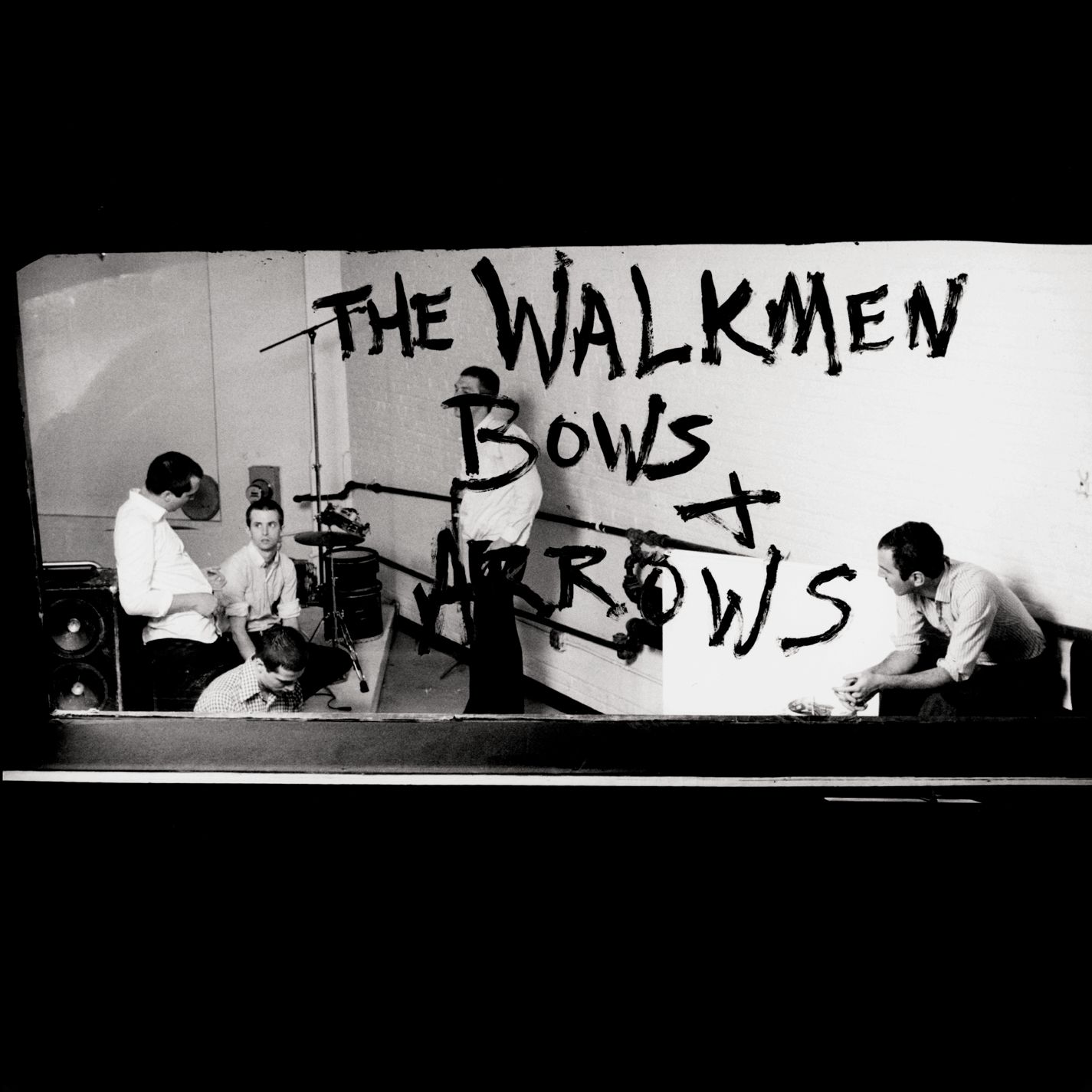

The Walkmen's second LP, released 20 years ago this Saturday in the US, is one of those rare miracle records where so many variables intersect: a surge in intangible energy, a burst of elevated songwriting, a singular aesthetic coming into focus. In terms of exposure, the Walkmen surely benefited from the media-abetted New Rock Revolution (of which they were theoretically a part) and the popularization of indie via The O.C. (on which they performed multiple songs from this album while Seth Cohen's exploits ensued). But Bows + Arrows would be a classic even if it was never on-trend.

On their 2002 debut Everyone Who Pretended To Like Me Is Gone, the Walkmen had introduced an undefinable but unmistakable new sound. Leithauser's vocals, piercing and raw, were only part of what made this band stand out. There were bits of the garage rock and post-punk that was coursing through every hip New York band at the moment, but just as prevalent were off-kilter old souls like Bob Dylan, Tom Waits, Harry Nilsson, and the Pogues, whose influence spiked the music with shades of folk-rock and the Great American Songbook. The result was music that often rocked hard but just as often wobbled with the grace of somebody stumbling home from the pub — jangling, droning songs where old pump organs and parlor pianos shared space with unhinged drums and electric guitar. It was as if they were tuned into the same obscure wavelength, with the shared intuition of friends who'd been playing music together in various configurations since they were teenagers in D.C.

If the debut had introduced the Walkmen template, Bows + Arrows perfected it. Minimalism and repetition loomed large; some songs were built on ceaseless ramshackle grooves, and Bauer played the same bass note throughout all four minutes and 41 seconds of "My Old Man." A deconstructed, Yankee Hotel Foxtrot-style approach to mixing and arrangement lent surreal qualities to songs as different as the shapeless Irish dirge "No Christmas While I'm Talking" and the clanging, glittering finale "Bows + Arrows," a song that seems to levitate but also hits like heavy machinery. Smart production choices made the album irresistible, but so did inspired songwriting — from sparse ballads like "138th St." and "Hang On Siobhan" (based on an old recording by cousins Leithauser and Martin's grandmother) to clattering, combustible triumphs like "Little House Of Savages" and "Thinking Of A Dream I Had" (which really does sound like a train barreling straight for you).

At the center of it all was Leithauser, throwing every bit of his ragged tenor into wild exclamations about a young ruffian's life in the city. The romantic discord ("I've seen you with your new boyfriend!"), the macho posturing ("You're an old friend/ We both know I could take you out"), the annoyance ("You don't have to say it again/ I heard you the first time"), the perpetual thirst for adventure ("Somebody's got a car outside/ Let's take a ride!") — it's all so electrifying when he's yelling it as if hanging out the window of a cab, waving his fist. The moments of quiet, when he sounds like he's curled up in the corner of a bar nursing a bottle of liquor, are nearly as affecting. The band's fragile balance between sophistication and barbarism owes so much to him.

Bows + Arrows came together haphazardly. The band did some writing at their home base of Marcata, a studio near the West Harlem brownstone where several members lived. They also retreated to an Upstate farmhouse belonging to Matt Stinchcomb from the French Kicks, where the shower ran with sulfur water and the band didn't get much done (though it was there that they built the transcendent "Little House Of Savages" out of unused parts from Martin, Barrick, and Maroon's old band, Jonathan Fire*Eater). After recording half the album in Memphis with engineer Stuart Sikes at the famed Easley-McCain Recording, a hurricane knocked out the studio's power, forcing the band and Sikes to relocate to Sweet Tea Recording down the road in Oxford. Leithauser once told Zane Lowe he consumed so much barbecue, Coca-Cola, and bagels with cream cheese during the weeks down South that when he returned to New York, his girlfriend was startled at his weight gain.

At their record label's behest, they tracked "The Rat" three different times in search of a properly emphatic take, which they landed on in a contentious one-off session with producer Dave Sardy. (Perhaps the negative energy in the room gave the track some extra pissed-off edge.) Even after all that, the album still lacked an intro, so back home at Marcata, they pieced together opener "What's In It For Me" out of a previously shelved chord progression at the last minute.On the Life Of The Record podcast, the band talked about running a vacuum cleaner through Martin's Hammond S6 pump organ to create the otherworldly blown-out sound that blurs into Maroon's tremolo guitar, giving you the sense that you're waking up in the Walkmen's world.

It was a place not everyone gravitated to. The Walkmen became both less famous and more consistently great than a lot of their hyped-up early aughts peers. Over the next decade, as indie rock kept getting younger and poppier, this band went in the other direction and became a refined, mature alternative. They never graduated beyond large clubs, and when they reunited last year, they were not headlining festivals. But they built up a devoted following and a discography so strong that many fans cite other Walkmen albums as their peak. They became the kind of band people tend to take for granted, and then they got up, got out, and moved along. But even at their least appreciated, not many would have denied the brilliance of what the Walkmen accomplished here.

Stereogum is an independent, reader-supported publication. Become a VIP Member to view this site without ads and get exclusive content.