We've Got A File On You features interviews in which artists share the stories behind the extracurricular activities that dot their careers: acting gigs, guest appearances, random internet ephemera, etc.

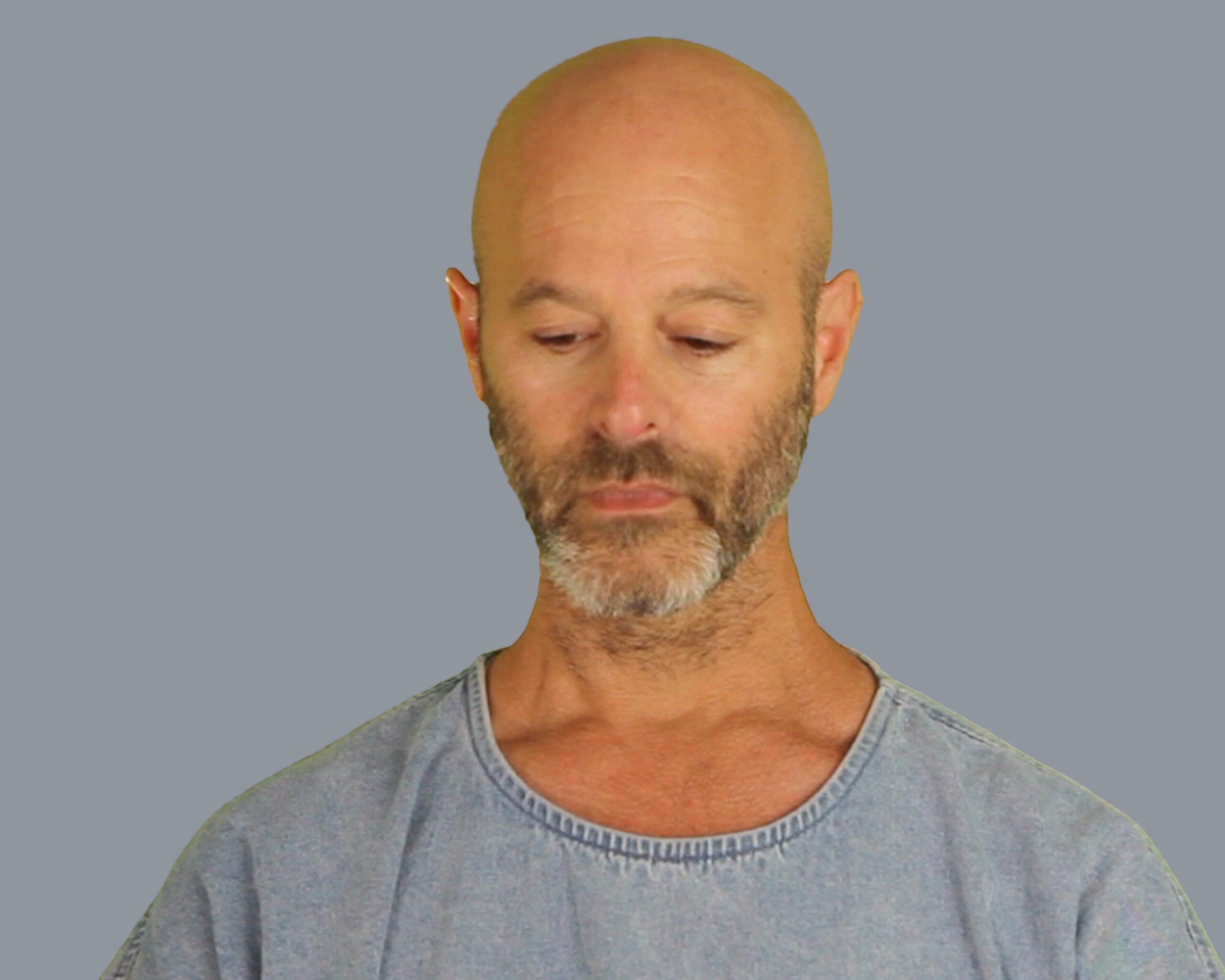

He walks into the artfully dingy laundry room, and just before he steps aboard one of those elevators that only existed during the MTV heyday (you know, the type that somehow lets you peek into every room you pass) he turns to the camera. His shirt is skintight, his scalp is bald, both ears are tastefully pierced, and his goatee is simply the ne plus ultra of adventurous '90s facial hair. He's hot, he's confident but vulnerable, he's intimidating, and he's perhaps a bit perplexed, judging by his opening line of "Say what?"

Or perhaps he's just helpfully expressing what every viewer will think the first time they watch the "X-French Tee Shirt" video or encounter the more outré moments of the Craig Wedren catalog, of which there are many.

Shudder To Think's video for "X-French Tee Shirt" was one of the stranger moments of the '90s Alternative Rock boom, a disorienting visual for an even more disorienting song, one that managed to be sexy, disquieting, and bombastic in equal measure, completely indifferent to traditional pop structure and powered by Wedren's operatic, post-hardcore Freddy Mercury wail. The single is the most well-known salvo from the DC-via-New York band's 1994 Epic debut Pony Express Record — proof positive that even the weirdest bands could get a major label deal post-Nirvana, and could use said label money to make a masterwork of alternate dimension progressive pop.

Wedren grew up as a classic rock and pop kid in Ohio and was already singing in cover bands by middle school. He moved to DC to live with his dad just as the city's hardcore scene was undergoing a mutation that would bring forth the first waves of emocore and post-hardcore. As a teenager, he joined a friend's hardcore band, which slowly evolved into Shudder To Think, and as he got older he split his time between band practice in DC and his studies at New York University.

Eventually, Shudder To Think mutated from a very good post-hardcore band, as documented on their 1988 debut Curses, Spells, Voodoo, Mooses to something much more singular on their beloved trio of Dischord dispatches: Ten Spot, Funeral At The Movies, and Get Your Goat. Released between 1990-92, they documented Shudder To Think's transition into a post-everything group, incorporating bits of sleazy glam rock, opaque prog, byzantine art-rock arrangements, and serrated post-punk riffs mixed with R&B grooves, all topped off by Wedren's distinct vocals. By the time of Pony Express Record, founding guitarist and drummer Chris Matthews and Mike Russell departed. Guitarist Nathan Larson and drummer Adam Wade joined Wedren and bassist Stuart Hill for the MTV era.

Shudder To Think is the sort of band often deemed a grower, where nothing makes sense until it finally does, and once you crack the code you wonder why more bands can't sound this forward-thinking. Of course, this approach often meant they went over many people's heads, which led to certain kinds of aficionados deeming them the most underrated band of the ‘90s. They were also the consummate band's band, as no other group can boast that they recorded for Dischord, opened for the Smashing Pumpkins on the Siamese Dream tour and Foo Fighters on the Colour And The Shape tour, and worked with Jeff Buckley and Liz Phair, amongst many others.

Following the soft reception to 1997's somewhat more pop-friendly 50,000 B.C., Shudder To Think became a boutique soundtracking operation for a bit, overseeing and contributing music to three films in 1998. They provided the score for Lisa Cholodenko's debut High Art. For former Lemonheads member turned director Jesse Peretz's debut First Love, Last Rites, they recruited friends such as Buckley and Billy Corgan to make an album-length mash note to classic rock and pop. They also teamed up with members of Radiohead and Sonic Youth for a series of glam-rock covers and soundalikes for Todd Haynes' Bowie fantasia Velvet Goldmine.

While Shudder To Think were enjoying their Buzz Bin moment, Wedren's NYU friends in the State were busy redefining sketch comedy for Generation X. He provided the theme song for their MTV show and later contributed music to their DVD box set. MTV had a deal with bands that they could use their music for TV shows such as The State and Daria, but that deal didn't account for home releases. When The State arrived on DVD in 2009, Wedren contributed facsimiles of songs like the Breeders' "Cannonball," which originally scored scenes.

After Shudder To Think ended, Wedren split his time between film work and his solo career, scoring TV shows such as United States Of Tara and Reno 911! and writing songs for the State's cult classic Wet Hot American Summer. He also kept collaborating with younger artists such as Bright Eyes' Conor Oberst while making solo albums, and he's continued to experiment by making 360 degree drone videos for his 2011 release Wand and virtual reality experiences for his 2017 release Adult Desire. His latest solo release The Dream Dreaming is one of his most sumptuous releases yet, a true melding of his skills with orchestral arrangements and love of electronic pop.

And in a strange twist of fate, one of the most elusive figures of the '90s has recently found his greatest mainstream recognition for providing, alongside That Dog's Anna Waronker, the theme song for Showtime's Clinton-era cannibal thriller Yellowjackets, which he recorded in the home studio he Zoomed in from. It's another unexpected highlight in a career full of them, and a tribute to Wedren's tendency to pop up where and when you least expect to find him.

Below, stream The Dream Dreaming and read our conversation, edited for clarity and concision.

The Dream Dreaming (2024)

So you started The Dream Dreaming album during the pandemic, right?

CRAIG WEDREN: Yeah, it didn't start off as a record. It started off as a series of singles. I didn't want to have to think about theme or sonic continuity or this or that style. I just wanted to make whatever I wanted to make because we were just stuck up here going crazy. And personally, I just needed to have some fun. But then, of course, as is often the case, you start seeing connections between things, and it felt like more of a single canvas than a bunch of little portraits.

When did it evolve into the synth pop orchestral thing? It feels more akin to your soundtrack work than anything else I think I've heard from you.

WEDREN: I think at this point everything just bleeds into everything else. The Dream Dreaming is not a not a collage or an amalgam of everything, but just a point at which everything that I've ever done has kind of all synthesized together, to mix my metaphors, in one sick gumbo.

You have a song called "You Are Not Your Feelings." That sounds like a variation on a comment that you hear a lot in therapy circles. Can you tell me more about writing that song?

WEDREN: That's so funny. I literally was just talking about this with my wife, Megan, a few minutes ago. We're living in this era, and I'm a pretty emotional guy or human. And I'm bored sick and nauseated by the out-of-whack over-importance it feels like we've been putting on feelings over thought lately.

For me, it was a reminder to myself of keeping my feelings in the passenger seat as a navigator with the map, not in the driver's seat with the hands on the wheel. I don't want my feelings operating heavy machinery, but I just want them to help me pick what machinery I want to operate.

You have a song with the refrain "Nothing bad will ever happen again." Was that a way to make yourself feel better during the pandemic?

WEDREN: The reason I kept it and it became the mantra song "Nothing Bad," is in 2018, I had a pretty massive heart attack.

God, I'm sorry to hear that Craig.

WEDREN: Yeah, thank you. I wound up getting five stents put in. It was a real shocker, especially because I'm generally a pretty healthy guy, and I take care of myself, and I eat well. I suspect it was long term tissue damage or compromise from when I was radiated in my 20s when I had cancer because they treated my neck and chest area. And that can have long term deleterious effects.

That said, I think that to, again, going back to being stuck in the pandemic with thoughts rolling and cycling over and over... the line is, "I survived and nothing bad ever happened again," which of course is impossible, and also what we wish for. And there was something sort of darkly amusing about that, and sweet. No matter how many hurdles or visits to the ER, you're like, "Okay, well that's that. I've cashed in all my drink tickets for bullshit, and now nothing will ever happen again."

How are you feeling these days?

WEDREN: I feel great.

Glad to hear it.

Moving To DC And Coming Of Age During Hardcore's Revolution Summer (1985)

I'd like to start at the beginning. What are your memories of growing up in the hardcore scene in DC in the '80s?

WEDREN: So actually, most of my formative years were spent in Cleveland, Ohio from about age, I don't know, probably four to 16. My dad moved to DC because he bought a hamburger chain. It's a slider chain in DC called Little Tavern; anybody who lived in DC in the Beltway area in the '80s will know it. It's sort of iconic, but gone now. I needed to get the hell out of Dodge aka Cleveland in the '80s, so I moved in with my dad in '85 or '86.

So I was only there for a couple of years. But I had been going to visit him on vacations like you do. And so I was passingly familiar with the hardcore scene on a surface level, the biggies, you know, Minor Threat, Bad Brains. By the time I got there, it was at the end of what came to be known as Revolution Summer. So Rites Of Spring became my instant ultimate favorite band. I only spent, like, two years full-time in DC, because then I went to college at NYU.

And so I was so I was going back and forth for a bunch of years through college. The band was in DC, I was in New York, so I was taking the Amtrak. So over those years, I became very familiar with, I guess at that point you would call it the post-hardcore scene, because things are getting more experimental and less like strictly "whack, whack, whack." I feel like when people say the DC hardcore scene, what they mean is (Ian MacKaye's label) Dischord, usually. But it was really much broader and more varied than that. Obviously Shudder To Think wound up on Dischord, and that remains very near and dear to my heart.

I read a profile of you in Magnet and learned that you and Shudder guitarist Nathan Larson ran an ice cream stand at hardcore shows.

WEDREN: It wasn't at hardcore shows. So basically, the summer before college, my dad encouraged me to do something entrepreneurial, and I wanted to do something where I could hang out with my friends and hire my friends and we could all hang out and talk about music. So we settled on an ice cream stand, and at the time, you could just get a little Ben and Jerry's ice cream cart that you could then fill it with all sorts of different companies. And my dad had all these restaurants, including one right in the bull's eye of Georgetown on Wisconsin and N street.

I set up this ice cream stand, hired my best friends Nathan Larson and Chris Matthews, the other guitar player in Shudder To Think. And basically no one would buy ice cream from us because we were blasting like Bad Brains and Minor Threat and Misfits and whatever else. And everybody had funny hair. It was a very commercial corner, so people were a little bit afraid of us. But mainly, we ate the profits.

So even in the early days, you had a really commercial lane, but you still were too weird for the masses.

WEDREN: Exactly.

Shudder To Think's First Album Curses, Spells, Voodoo, Mooses (1988)

On the first Shudder album, you're doing more singing than is common in the post-hardcore genre. There's some weird touches, but it also still kind of feels like the era and scene. But from the start, were you still trying to differentiate yourself? And what were the early days of Shudder To Think like?

WEDREN: So Shudder To Think, before I joined, was a band called Stüge. They were very much a DC hardcore band. And their singer Bobby went off to college. I was in high school with Chris Matthews' girlfriend, he was the guitar player in Shudder To Think for the first six years. Anyway, she passed me a cassette of her boyfriend's band who was looking for a singer. I listened to it. It wasn't really my style. I was, again, coming from Cleveland, there was less delineation between sort of underground scenes there because there just weren't that many of us. So I was coming from New Wave and goth and post-punk and punk and hardcore and disco and pop and whatever else.

So I had been singing largely in cover bands in Cleveland from like seventh, eighth, ninth, 10th grade, and that stuff was just more melodic singing. I just was never really much of a screamer. There were some screamers that I loved listening to, like Germs or Black Flag or whatever, but just honestly, I just never understood how to do that. And it didn't feel good to me. I come from a melody family, too. My mom is like Simon and Garfunkel, not Bob Dylan, you know what I'm saying? And they were sort of opera people.

So I grew up in a house where melody and prettiness was paramount, and I think it just came through in my singing. So what I was coming with was this very melodic sort of singing at the top of my range, probably from singing Steve Perry and Ozzy Osbourne songs. So I went and auditioned for Stüge. They were a hardcore band. I was this kid coming from Cleveland, and it just was a chocolate in your peanut butter moment where, at first we were sort of cringe, then by the end, we're like, "This is kind of rad. This is really something unique happening here."

And I think once we once we all realized it... because everybody who's ever been in Shudder To Think are very thoughtful, aesthetically broad-minded characters. So everybody was into literature and film and music of all kinds. It just so happened that hardcore was the thing that was happening at the time. So that's what we were doing. But then I think once we all heard this kind of synergy, that there was this newness and an unexpectedness to what we were doing, that became our M.O. and then it just mushroomed from there. So even on the first record, you're still getting the kind of two sides a little bit, but it's starting to come together. We're still feeling our way through.

Early New York University Days, Funeral At The Movies/Get Your Goat (1991-92), And Becoming An Unofficial Member Of The State

So for a while, you're going back and forth between NYU while also working with Shudder To Think. Were you still at NYU during the Get Your Goat and Funeral At The Movies era?

WEDREN: I was at NYU during Get Your Goat and Funeral At The Movies. We'd recorded Curses by the time I went to college, I don't think it out yet.

But anyway, we had some pretty neat, unique stuff recorded by the time I went to school. Ten Spot and Funeral At The Movies were very much dorm records. I was living in the Brittany dorm on 10th Street and Broadway with (future members of the State) David Wain and Ken Marino. And I was very involved with the whole crew that would become the State.

I was about to ask.

WEDREN: I was studying experimental theater with some really amazing, interesting people in the experimental theater program. Anohni was in my program. So there was this experimental side of abstract voice and sound installation stuff. And then on the other hand, there was the span that I was in that was very much song based. And so then the whole film scoring and sound environment and sound design for theater was happening at the same time.

So the State would need a little piece of music and I would put something together and I would go back and forth on weekends to DC to rehearse or play shows or record or Shudder To Think. And then there was this more experimental stuff. So it's all always been there, it was just a question of when things started hitting, but most of the vocals and lyrics for Ten Spot and Funeral At The Movies were written on the Amtrak between New York and DC, specially Ten Spot. It's very dreamy in that respect. And you can sort of hear the classes that I was taking because I took, like, a surrealist class, and you start hearing very sort of 19-year-old surrealism 101 imagery creeping in.

One of my favorite Shudder To Think songs is "Day Ditty." Could you talk about that one a bit?

WEDREN: Yeah, sure. "Day Ditty" was interesting. I want to say it was 1989. Shudder To Think was on tour in Europe and we were staying in straight-up squats. It was a lot of hardcore political European punk squats.

Right.

WEDREN: Which really wasn't our music. It wasn't really us. There were some lovely people and some really fascinating encounters. But we were in some squat, I want to say it was in Germany, everybody was staying up all night, smoking hand-rolled cigarettes and talking about anarchy or whatever. I don't mean to be dismissive, but it was sort of Greek to me. I had really long hair for a really long time, and it was starting to thin. I could tell it was starting to thin. I don't know if anybody else could. And I was exhausted, because you would play these shows extremely late at night, I would be having to shout as loud as I could to be heard on the weak PA systems relative to the Marshall amplifiers that we were carrying and it was just very hard to find a comfortable place to rest.

And somebody was always sick. So I was feeling really depressed and so far from home in so many ways. Chris Matthews, the guitar player, was sitting in the corner. He was playing an acoustic guitar and he was doing that C-F motif, very sort of Velvet Underground thing, and talking politics and drinking espresso and smoking hand-rolled with the German squatters. I went into the bathroom and I just shaved my head, just really fast. It was the first time. And my hair had always been a very defining part of my identity for me. So it was a big deal to me, and I walked out of the bathroom and everybody stopped. The conversation stopped. Chris stopped playing. I think it took people a sec to even kind of put together that I had walked in there. I was feeling very inspired and kind of wired, and I was like, "No, Chris, keep playing that thing." And he started playing that c-f thing, and five minutes later we had "Day Ditty." It was one of those little dreamy gifts.

Working With The State And Writing The MTV Show's Theme Song (1991-1995)

Let's go back to what you were mentioning earlier. Could you tell me about when you first met the members of the State? Were you there when they formed? Because you've always been one of those unofficial members and more or less their musical director.

WEDREN: So David Wain and I grew up together in Cleveland, and we went to NYU together. So we were roommates. We met Ken Marino on the very first day of college. We all fell in love and became roommates.

And then gradually, this comedy group called the New Group, which is what the State was called before it was the State, formed. Tom Lennon, Kerry Kenney, Joe Lo Truglio, they were all a year younger than us. So maybe it didn't start until David and Ken and I were sophomores. But it was just our crew. It was our group of friends. And Kerry and I dated when she was a freshman, and I was a sophomore, which was right around when the New Group was starting, I think. I always thought they were brilliant. And the funniest thing going from the get go.

I was just sort of a part of the posse and one of the musical go-to guys. Eventually, Theodore Shapiro, who went to Brown and also scored a lot of the State stuff, he and I collaborated on the Wet Hot American Summer score and songs and soundtrack and things. If you're lucky, you have this posse of magical weirdos in college, and mine happened to be that crew, and we were just all very well-suited because we were all kind of psycho driven and ambitious, me with music stuff, they with comedy and theater and just general brilliance.

So I was just always around, and when they started for the first handful of years, before the MTV stuff happened — which was, I think, right when we graduated — they would just do theater shows in black box theaters around NYU, and they would need sound design or someone to run lights. And I was happy to oblige.

I interviewed you a million years ago when I had a job at CMJ, right around when The State DVD box set finally came out, and I told you that I always thought the lyrics to the show's theme songs were "Boys and girls/ Spatula!" But it's not.

WEDREN: [Laughs] Action, go!

So tell me about making the theme song.

WEDREN: "Boys and girls, spatula?"

Yeah.

WEDREN: At the time, I guess it was like, I don't know what it was, but if memory serves, which it sometimes does, I was living with my friend Jesse Peretz. I had this Akai S950 sampler, which to this day is my favorite sampler, and it was a mono thing. But something about the compression that it did to everything, it just made everything rip. And so I was just constantly in a very kind of sampledelic phase of writing, not for Shudder To Think stuff, but for just my own bedroom experiments. They asked me to come up with some theme song ideas because they had just signed this deal with MTV. I think I got like $500 for it or something like that. So I had sampled... my ear at that point was just very attuned to anything that would make a good clip, and that included [DC band] Nation of Ulysses.

I don't know what the song is that has "boys and girls and action," but it's two separate lines, I think, from the same song. Definitely from the same album. [The songs are "The Kingdom Of Heaven Must Be Taken By Storm" and "The Hickey Underworld" from the 1992 album Plays Pretty For Baby.]

So they were just Nation Of Ulysses samples that I had cut up at a certain point, and I was just messing around. I mean, there's so much illegal shit in that theme song that I did not get permission for. I was able to call Ian Svenonius and be like, "Dude, I'm doing this thing."

But there's so many beats in there which if they ever came to light, it would be really bad because I just did not care. And at that time I was in my early mid 20s and the creative act and the creative process and the quality and magic and energy of the music was much more important to me than the law.

So I was just like, "I don't care." And so there are all these really, really neat, strange samples in there. And I mapped it all out on my keyboard for the samplers so I could essentially play all the samples in the shape of The State theme song. And I also sampled myself playing ukulele and singing the "No, no, no, ohhhh" stuff. And I just really just smushed it all together, spat it into like a DAT tape or... no, it was probably inside my sampler or something.

And then I got together with [Girls Against Boys member] Eli Janney and we polished it up and mixed it. And that was the State thing. There were a few others that were really cool. There was one that was very kind of Devo-like, and there was one that was very kind of Captain Beefheart, but they liked the Nation Of Ulysses one.

Graduating NYU, Leaving Dischord, Signing With Epic, Releasing Pony Express Record (1994)

So around this time period, you've graduated, your friend Nathan Larson has joined Shudder To Think, and you signed to Epic Records. Back in the '90s, there was a huge fear of selling out. When telling younger people about that sort of thing, they tend to roll their eyes. But you were leaving Dischord Records, one of the most hallowed major independent labels of all time. Were you afraid of a backlash? And what made you decide to sign with a major?

WEDREN: I was not afraid of that. Eh, you know, I shouldn't say that. I don't remember if I was afraid or not. I would say Stu, the bass player who founded Stüge, and it was really his band, he would have been the most staunchly political about it. Probably Mike Russell, the drummer for the first five or six years, had something to say about it. I'm sure we talked about it a lot. The original lineup went all the way through to Get Your Goat, which would have been like '91 or '92, '92 I think.

By that point, I was graduating college. Everybody else was joining the workforce. Everybody had jobs, right? They were all older than I was by at least a year. So it was sort of shit or get off the pot. And I was never shy about my ambition, which was I want everybody to hear my music, our music, this music. Whatever music I was involved in, I wanted it to reach as many people as possible. I think I was just raised in that kind of a household where it was like, "No, you go for it." There wasn't any there wasn't any sort of indie...that thing that artists put on themselves about selling out. "Is this selling out? Is this not selling out?" Especially because no way were we selling out artistically.

So that's what was important. As long as we weren't selling ourselves out, musically, you can put us on the tip of a rocket and shoot us into space and put a Coke label on it, I don't care.

What do you remember about making Pony Express Record? Because you have that kind of thing that Pink Floyd or Soundgarden or Sonic Youth had, where it's like really strange chord changes, arrangements, tuning, all that stuff. But it still somehow scans as pop music, at least to me. Was there any kind of push to make it more easily accessible?

WEDREN: No, I mean, that was what we were working on after Get Your Goat. It's interesting, I think of Get Your Goat and Pony Express Record as sort of two sides of a coin, even though it's sort of two different bands or half different bands because, Get Your Goat was the last one with Chris and Mike. Pony Express Record was the first one with Nathan and Adam. But at least what I was working on as a songwriter, it was very similar stuff. It was about this tension that I think often still is with some of my music, this sort of titillating thrill that I get when something embeds itself, the way hooks do, but also kind of destabilizes you, the listener. I just love that feeling.

I might liken it to the way I feel or used to feel watching David Lynch movies. There are all sorts of movies and literature and art, and it's sort of a dream sensation or a thrill ride sensation where you're in a dream, everything's off, but it somehow makes perfect sense. You bring the information back home and the next morning, you're conscious again. You still have the kind of dream dust that's slightly sickening and slightly thrilling. It's sort of like falling in love or sort of like lust or something like that. And so we just knew when we all felt it, when we all felt that way.

That was the kind of stuff I was writing and at the time, we were all on the same page. So Nathan's contributions were very much in that realm. And the things that Nathan and I were into, we were sort of joined at the hip, the things that we were talking about, the things that we were into: movies, magick, beauty, John Cage, whatever it is, it was just all getting in there and there was a mind meld. So we were working on all of that, while the whole Alternative Boom was happening. And bands were getting signed left and right everywhere, post-Nirvana. We were thrilled and excited to try and step it up and reach more people. One can argue in the rear view in retrospect whether that was a good move or a bad move. But we were like, well, lightning like this isn't going to strike twice.

Of course.

WEDREN: Because we are getting offers from really good record labels based on arguably the most difficult music we've ever made. And some of the more challenging pop music or rock music stuff out there. People seem to be loving it. So it was this really great moment, and we were not about to let a conservative mindset hold us back.

With Help From The Likes Of Jeff Buckley And Billy Corgan (But Not Björk And David Bowie), Shudder To Think Make Or Contribute To Three Soundtracks In One Year: First Love, Last Rites, High Art and Velvet Goldmine (1998)

I want to jump ahead a little bit. In 1998, Shudder To Think released three different soundtracks. What do you remember about making the First Love, Last Rites soundtrack? I really mean no disrespect to Jesse Peretz, but I'm willing to call your work the best soundtrack to a movie almost no one's ever seen.

I couldn't find the movie on streaming, and I know it got mixed reviews, but maybe it holds up. I can't say. But I know the soundtrack really holds up.

WEDREN: Thank you. What do I remember about that? Well, that was actually a really nice moment. So Pony Express Record happened. We signed to a major label. We did the whole thing. It was, predictably, like a mixed bag. There were wonderful things about it and difficult things about it. It didn't perform commercially as well as it needed to in order to justify investing in us at that level again, unless we were going to make some hits.

So we made 50,000 B.C. Well, so we started working on the new record. The band really started pulling apart at that point. It's no longer a mind meld. No matter what I brought into the rehearsal space, it was like molasses. It's just some stuff that I thought was great... but I don't know what was going on, but everybody, everybody wanted different things, especially Nathan. And then I was diagnosed with cancer, Hodgkin's Disease. It was '96, I guess, maybe. And that really pulled us back together. Because we were and remain very much a family, even if we're not in touch that much anymore. Like, we love each other a lot. And it's really just a good, good bunch of us.

That was, I wouldn't say a wake up call, but it reminded us about what's important, as that will. At the same time again, I think I was still living with Jesse at that point, maybe not, and he was making his first movie. It was a very low-budget indie, and one of the main characters had a collection of 45 singles that were to be essentially the soundtrack to the movie. They didn't have a licensing budget to license all these oldies. And so he asked if we wanted to write all of these genre songs, and we were thrilled. We were in a good place again. It was after 50,000 B.C. because we made that while I was undergoing treatment. And it was actually really great. We found a harmonious little break in the weather there. Then afterward, 50,000 B.C. did not... like our A&R guy had left Epic Records, there had been a big turnover, shakeup, whatever. Music< was changing, it was starting to become, like, on the alternative side, it was like Tool and Korn, and then it was like boy bands.Real '97 vibes.

WEDREN: Yeah. '97 vibes. So we weren't, we just weren't really going to fit. We had already decided at that point that we wanted to start focusing on film soundtracks, and to sort of turn Shudder To Think gradually into almost like a soundhouse where we would make our records, when we wanted to make our records, we would tour and perform when we wanted to tour and perform, we would compose music for movies and TV shows and fashion shows or whatever else it was, and produce things for other artists to. Essentially what I do now and what Nathan does now, but together as a group.

We just weren't really able to hold it together for that long. But the first two soundtracks, we did were First Love, Last Rites and then High Art, which was Lisa Cholodenko's first movie, were really just extraordinary experiences. They were wonderful, wonderful ways to sort of wrap up the band or begin to transition into whatever it was we were going to become. So Nathan and I really hunkered down for First Love, Last Rites.

He wrote a bunch of songs, I wrote a bunch of songs, and then we wrote a bunch of stuff together and just worked on it very much in like four-track mode, like in his place or at my place. And then for a few of the bigger songs that we knew were going to have features, we went into a proper studio and recorded "I Want Someone Badly" and "Speed Of Love." Also, I was obsessed with the Cardigans. They just put out First Band On The Moon right during, I think, the Pony Express Record promo time, and I got the CD and I remember it was just like, "This is it. This is like the future." Or it was what I wanted to be. The future of pop music.

I had written this sweet little kind of Hawaiian lullaby that we knew we wanted to use, and I was like, well, "I want Björk to sing it." Because we had some clout at that point, so we could sort of pick and choose people we wanted. And we were friends with Billy Corgan, and we were friends with Jeff Buckley, and so those names really opened up a lot of doors and gave us entree to all these other great people. And I was like, well, I want Björk to sing this song and if not Bjork, then Nina Persson from the Cardigans.

So I was given an audience with Björk at this little bar one evening because her tour manager or assistant or something was a Shudder To Think fan, which was incredible. So I was at the Buddha Bar, I think, and the manager, she was like, "Okay, listen, you got 10 minutes with Björk, make sure you have your shit together. Have your pitch down, have the song, do the thing. Great." So, like, I walk up, I go in there, I have my manila folder with probably a copy of "Appalachian Lullaby" on it with me singing. And I love Björk.

Of course. Who doesn't?

WEDREN: Yeah, exactly. And there are only, there are only two times where I've utterly choked. And that was one of them.

Ooof.

WEDREN: I went into this back room and it's just Björk sitting at a table. I'm like, "Hey, Björk." And I just sat down and just bit it for 10 minutes, so that never happened. But it turned out to be a blessing in disguise because we've got the song to Nina from the Cardigans. And then she and Nathan met and they fell in love. And they've been married ever since and have a 13, 14-year-old.

Amazing. Now, what do you remember about working with the late Jeff Buckley?

WEDREN: I remember the day in the studio with him. I mean, it's so extraordinary to listen to, to be a part of as an artist, that I don't even know how to put it. He was just brilliant.

It's an incredible song. One of his very best vocal performances, which says a lot.

WEDREN: He's just the best singer that I've ever had the privilege to work with or know. And as I said, like, I went to college with Anohni and I toured with Chris Cornell. But Jeff was operating at a once-in-a-generation level, in my opinion, and was just like a hilarious idiot in the best way. I mean just funny and weird and smart and a big nerd. It was thrilling and... intimidating isn't the right word. It's just more jaw-dropping, like when he just started putting those harmonies on and Nathan and I were like, "Wait, what? How do you know how to do that?" It took me 20 more years to figure that shit out.

That same year, 1998, you also worked with Todd Haynes on the soundtrack for Velvet Goldmine because, famously, David Bowie wouldn't let his songs be licensed for the film.

WEDREN: He was in a very hetero decade.

The '90s were weird for him. Now, what was that process like for you, and what was it like making those songs that, in the best way, were facsimile or soundalike David Bowie songs? And that later led you to your career where you're like, "Okay, Wet Hot American Summer needs a mock '80s AOR ballad" or "School Of Rock needs a fake post-grunge song for the enemy band."

WEDREN: It was the best. And it was great to have that invitation between First Love, Last Rites and Velvet Goldmine, getting to do these genre songs as an assignment. So remember earlier we were talking about, being totally unwilling to sell out creatively? We would never have let ourselves do that as a band under the Shudder To Think moniker of, like, original Shudder To Think music. Because that band's mandate was to create new original music that didn't sound like any other music. I mean, maybe we succeeded, maybe we didn't. But that was our priority. So it started getting really restrictive. We sort of created our own straitjacket, where we kept having to sort of up our art game.

But one of the reasons we, or at least I, started making music like that in the first place, Shudder To Think kind of music, was because there were a billion people making pop songs. It always felt like we could make a pop song if we wanted to make a pop song. But why do that? Like let's do what isn't being done and do something original.

So to be asked to kind of play in the sandbox of all our influences, because we all grew up with radio, of course, basically '50s through '90s rock and pop and dance and whatever else. Along with that, maybe even in particular the sort of early '70s Bowie, T.Rex, Roxy Music glam era was very deep in our DNA.

So really, I don't say this in a braggy way, it was just right there. "Of course we can do this." There were some other things like, on First Love, Last Rites, there were some things where we really had to take apart the watch and be like, "so how did the Zombies actually do that?" We know Odessey And Oracle and whatever, but to actually go in there and figure out what was the gear, what were the sounds, what are the harmonic ticks? But with Ziggy Stardust and Diamond Dogs-era Bowie, it required no thought. It was right there.

Wedren's Signature Look And "X-French Tee Shirt" (1994)

So I watched early Shudder To Think videos, including for "Hit Liquor." For that, you have a short haircut, no facial hair, and you're looking like a guy in a post-hardcore band. And then, boom, we get the video for "X-French Tee Shirt." You have the famous goatee. You're shaved bald. You and the entire band have a real grunge-glam look, which one cannot pull off unless you have 100% confidence. You guys are, as the kids say, swagged out.

How do you land upon that look? And what do you remember about making the "X-French Tee Shirt" video? Because it is crazy and looks pretty expensive for such a weird song.

WEDREN: Yeah, it's a crazy video. Uh, what I remember about that was…I'm embarrassed, I can't remember who directed it. [It was directed by Pedro Romhanyi.]

He came up with this treatment, and it was wacky and over-the-top and maximal in that way. And again, we were we were living out our rock 'n roll fantasies, or at least we were hoping to, It was a big-budget '90s video, and they were putting a lot of money behind it, and we were like, "Fuck yeah, let's do it." So they flew us out to LA, and they had built a whole set in a soundstage. I mean, it was like the real deal.

And there was this woman who was there as a makeup person, named Katinka Van Kirk, which I think was her last name at the time. I think it has since changed. Immediately the second I sat down in her chair, we just had an instant rapport with Katinka, it was like she was a member of the band. She was just down to play and explore and she just started painting my face. And two minutes later this eyeshadow glitter character came out and it was like, "Wow, you found me." It was incredible. I consider her a dear friend to this day.

And that was when we first met. As with so many people in my orbit, creative and otherwise, from David Wain and I meeting Ken Marino the first day of college to meeting Nathan in high school, to meeting Katinka, It's just been this sort of parade of magical playmates. And the "French" video had that aspect to it.

What did you think when your friend and fellow State associate, the director John Hamburg, styled the actor Keegan-Michael Key to look like you in the movie Why Him?

WEDREN: Well, I was very, very flattered. And first I was like, "Are you making fun of me?" I know Hamburg through Theodore Shapiro, he was part of that whole Brown contingent. There was like the NYU contingent and the Brown contingent, and then everybody came together after college. So 10 years ago, whenever he made it, he texted me and he was like, "Hey, send me a picture of your look, like your shaved head with chops thing." And so I found a picture. I sent it to him, and then he sent me back a photo of Keegan-Michael Key with the same thing. And I was like, "That's so awesome. He looks amazing. Um, are you making fun of me?" And he's like, "No, totally not. I love it, and I want this character to have that look." So it's very, very flattering.

So what exactly is an "X-French Tee Shirt"? I've wondered for a very long time.

WEDREN: I don't know. It's one of those combinations of words that gave me a slightly sexy sickly feeling.

I mean, it's definitely a tight shirt with short sleeves. But it doesn't mean anything. It's just something that, as with so much of the imagery on that record, if something gave me that feeling like I'd just been on the Gravitron ride, then I then I stuck with the lyric or if it gave me like a, like a Polaroid image, like something vivid in my head that I was like, "Mhm. Don't know what it is, but I know it makes me feel ways," then I kept it.

You said the album didn't do what Epic wanted it to do, but the "X-French Tee Shirt" was on MTV a lot around the time your friends had a TV show on MTV. What was that ride for you like, at least in terms of 1994 and '95?

WEDREN: I was about to say, "Oh, it was the best." And it was in many ways, but it was also really, really difficult. There's nothing I can say about it that you can't read in a million books about the record industry and about bands making their bid for the big time and it sort of splintering things interpersonally in the bands. But if you got to see us then, we were so good live. We were on point. It was really great to play together then all the way through 50,000 B.C., and we were probably even better around 50,000 B.C. It was just sort of a well-oiled machine, and we were very cocky or confident, like that, "X-French," sort of swagger thing, which I'm sure was a big turnoff to a lot of people, but it was really, really fun.

When you were touring with bigger bands like the Smashing Pumpkins or Foo Fighters, who were getting huge at the time, were you like, "I want this,"or were you more like, "I don't know, this looks kind of weird."

WEDREN: You know what? I think that was part of what it was. And it's still something that I think about. I'm like, "Oh, I wonder if we got close enough that we were like, yeah, that seems like I don't want to be strapped to that rocket," you know? I have friends now who, they're in their 50s and they still have to tour. And I assume that they love it. I don't know, but, it started becoming very clear to us around then that we did not want to have to do that treadmill of album promotion. There was so much else that we wanted to do. We wanted lives and families and community and to just make art for art's sake and to be able to do experimental things without having to run it up the corporate flagpole. As much regret as I sometimes regret that Shudder didn't, like, make it big in all caps -- I mean, we did nicely -- but also, the soft part of me is like, "Bullet dodged."

Collaborating With The Electronic Music/Indie Hip-Hop Artist Cex, aka Rjyan Kidwell (2002)

A favorite thing of mine that you did in the aughts, was you did a lot of work on the Baltimore rapper Cex's album Tall, Dark & Handcuffed. A forgotten gem, if you ask me.

WEDREN: Yes! I love, love Cex.

I feel he was so far ahead of his time, in a lot of ways. What do you remember about working on that album and collaborating with the younger indie/underground generation at that time?

WEDREN: I don't remember how I met Rjyan. I think he was probably a Shudder To Think fan because he was a Baltimore kid. I just remember going to see him, and he was just like in his, tighty-whitey underpants like in the middle of the audience, just rapping to some really edgy, progressive electronic beats.

Yeah, he was a wild dude back then.

WEDREN: Toward the end of Shudder To Think, as things were starting to splinter, I was getting more into the sort of late-'90s Warp, electronic stuff and Nathan and Stuart were getting more into rootsy, soul, Americana, things like that. No reason it couldn't all have worked out together. But, there was a pull in different directions. And I remember, I've just always been drawn to new sounds that I don't necessarily understand, but that make my whatevers fire. And Cex had that. His tracks had that. I don't remember how we wound up working together. I don't even remember what I did. Did you say I sang?

Yeah, you sang on a bunch of songs on the Tall, Dark & Handcuffed album.

WEDREN: I just sang on them. I don't think I did any production or anything like that. I don't remember how we did it. I think we just sent it back and forth in that kind of proto send things back and forth way that we all do now, but at the time it was still like half analog and half digital. Because I remember working on it, I was living on Stanton Street across from Arlene's Grocery, starting to work on some movies. I had this sort of dance pop band called Baby at the time. And then I was working on my first solo record and blah, blah, blah, blah.

There's a lot going on, and I'm just looking to collaborate with different people. I was collaborating with Cex. I collaborated with some house music people, and it was really creatively very liberating and very fun. Especially after, like I said, that sort of straitjacket that I think we all felt like we had found ourselves in with Shudder To Think.

Releasing Solo Album Lapland Via Conor Oberst's Imprint Team Love And Collaborating With Him Over The Years (2005-Ongoing)

So in the aughts, you're living in New York, you're soundtracking a lot of films, you're also releasing an album on Conor Oberst's label Team Love, and you've been tight with him over the years. He and other members of Bright Eyes collaborated with you on your album Wand. What has it been like, working with him?

WEDREN: Oh, that was great. So Nate Krenkel and he had this label called Team Love. And Nate was our publisher. He was one of our publishers at Sony Music Publishing. After the band broke up, he introduced me to Conor. And Conor was like, "Hey, if you ever want to put anything out, I have this label." And it was great because at the time, I had a ton of music, some of which was stuff I had started writing for future Shudder To Think things, and some of which were just things I had around.

I was sort of at a low end, right? I didn't really have a musical identity or a framework. I've been in this band since high school, Shudder To Think. And suddenly it was gone. And so everything felt very dislocated. And Kevin [March], who was the final drummer in Shudder To Think, and Carl [Glanville], who mixed 50,000 B.C., they really pushed me and spearheaded making Lapland, which I think I didn't fully appreciate or maybe even recognize at the time, probably because I was stuck in my own, you know, "woe is me"-ness.

That became the record that we did on Conor's label, and we just made it and turned it in, and then they put it out. Then I played guitar in a version of Bright Eyes one time in Brooklyn. It was like in an era where Conor would sort of roll through town and call up musicians that he liked and be like, "Hey, you want to be the guitar player for Bright Eyes?" At this point I can just like step in and bang it out with people. But at that time I was still very much in kind of Shudder mode, which was like, "Rehearse, rehearse, rehearse, make it tight." And his thing was like the Rolling Thunder Revue.

Right. Of course.

WEDREN: So we had a great time doing that. And actually, my wife just produced this movie called Alok, which is a documentary about a trans performer, activist, philosopher named Alok.

@audible The new short film, 'ALOK' offers a compelling profile of the gender non-conforming poet, comedian, speaker, and writer @alokvmenon. The documentary is executive produced by #JodieFoster and directed by AlexandraHedison. For poetic magic from Alok, listen 'Femme in Public' and 'You Wound/My Garden' now on Audible. ?? #Sundance #FilmTok

♬ original sound - Audible

And Alok's favorite artist is Bright Eyes. My assistant, Simón Wilson, and I did the score for the documentary, which is going to Sundance next week. So I had this excuse to call Conor, whom I had not spoken to in years — not for any reason, just because of life — and we just wrote this new song for the documentary, so we reconvened, which was great.

Writing And Recording, Alongside That Dog.'s Anna Waronker, "No Return," The Theme Song For Yellowjackets

OK, last question, and I think this is a great place to end it. We can't finish this interview without talking about your work on Yellowjackets.

What's it like for you having probably the biggest song of your career in a TV show about an era you participated in? What is that experience like for you?

WEDREN: It's so trippy. It's the snake that eats its own ass tail and barfs it back out and keeps eating it again. It's beautiful. I mean, Anna Waronker, my partner on Yellowjackets, she's having the same experience, and we just make all the music right here, and we just crack up about it. It is the best argument for living inside of a dream. I mean, it's like this canvas. This is the matrix, right?

We both have so much experience at this point, and sort of are able to move laterally through genres and ideas and styles and things without being precious about it, which is not something we were able to do when we had our band mind thing, Shudder for me and for her That Dog., in our 20s. It's really pure joy at this point. It's so fun.

Like finally in my life, I get to play music all the time. When Shudder was happening in my 20s, I was very perfectionist, very ambitious. It's definitely a function of being in one's 20s. It was great, but it wasn't fun. And it is mostly fun now. And then also it's like that trick with the Yellowjackets theme. In the '90s I would never have let myself indulge my inner Breeders or My Bloody Valentine or Jesus Lizard, overtly. But when you're doing a theme song or a show about the '90s, let's just pay homage to them. Let's just put all our favorite singers in there. And, and so we're able to do that, trust that it's going to be wholly original and hopefully like a genuine and worthy tribute.

I might be wrong, but I don't think the show has dropped a Shudder To Think needle drop in the actual soundtrack yet, but hopefully we get that in the third season.

WEDREN: I feel like Shudder To Think is ripe for some '90s rediscovery.

The Dream Dreaming is out now on Tough Lover.

Stereogum is an independent, reader-supported publication. Become a VIP Member to view this site without ads and get exclusive content.