Camera Obscura owe their reunion to a rock cruise. More specifically, an exceedingly twee indie-rock voyage hosted by fellow Glaswegians Belle & Sebastian. In 2019, Camera Obscura — on extended hiatus since the death of longtime keyboardist Carey Lander — accepted a personal invitation from Stuart Murdoch to join them, Mogwai, Teenage Fanclub, Yo La Tengo, Alvvays, and more, on the Boaty Weekender, a nautical festival around the Mediterranean aboard the Norwegian Pearl.

Lead singer Tracyanne Campbell was hesitant at first. It had been years since Camera Obscura had played together, let alone played without Lander. But today, as she and the beloved indie-pop group prepare to release their first album in a decade, she owes a debt of gratitude to the Boaty. Not only did the experience remind her what Camera Obscura meant to fans from as far away as Japan and New Zealand, it unleashed a fresh bout of songwriting.

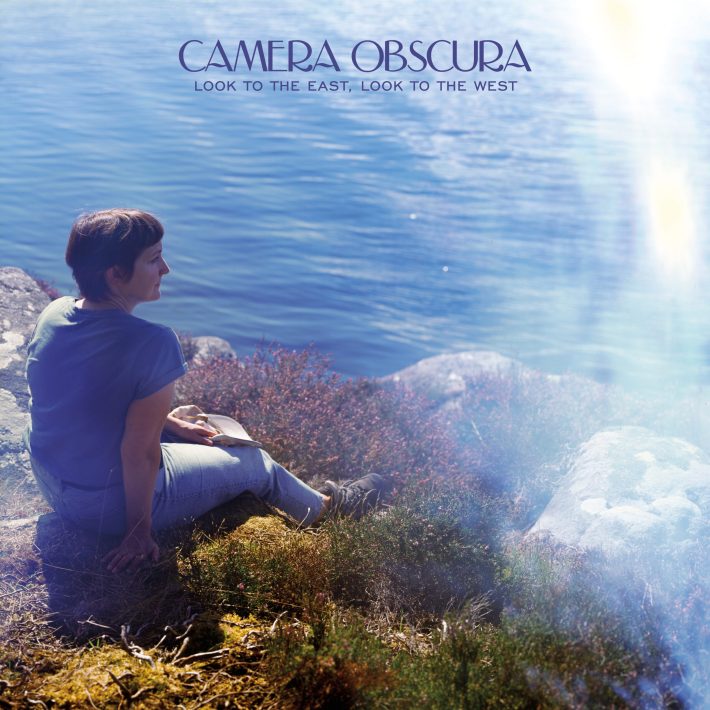

The result is the 11-track Look To The East, Look To The West, a characteristically thoughtful, melancholic, and melodic journey that reunites Camera Obscura with producer Jari Haapalainen, who also helmed the band's landmark albums, Let's Get Out Of This Country (2006) and My Maudlin Career (2009).

Following the release of the album's first single, "Big Love," today Camera Obscura are sharing the tinkling, facetious follow-up, "We're Gonna Make It In A Man's World." Of the track, which is a co-write with new keyboardist and vocalist Donna Maciocia for Margaret Salmon's 2021 film Icarus (After Amelia), Campbell says: "It is a bit tongue in cheek with a serious message at its core. As middle-aged women in the music industry, are we relevant? Who is interested in us? Where's our place in an industry where women are so underrepresented?"

Campbell adds of Salmon, who also shot Look To The East’s cover art: "During lockdown in 2021, Donna and I had collaborated with her by writing 'We're Going To Make It In A Man's World' for her 35mm film Icarus (After Amelia). So, in some ways Margaret was also part of the inspiration for some of the record and part of the process."

Ahead of releasing Look To The East, Look To The West (coming May 3 via Merge), which was put on hold in part due to the pandemic, Campbell hopped on a Zoom call to reflect on Camera Obscura finding their way back to each other, grieving Lander in ways big and small, what the Boaty Weekender inspired in her, and much more.

Below, hear "We're Gonna Make It In A Man's World" and read our conversation.

I'm going to level with you—I literally squealed with excitement that Camera Obscura were putting out a new album. How has the response been on your end?

TRACYANNE CAMPBELL: My sense is that I've not paid too much attention to it really, because I've been busy the past few days. I don't really go on social media a lot, to be honest. I don't find it very helpful for me personally. But I gather that there [are] a lot of people excited about it. When the band went to play the Boaty Weekender with Belle And Sebastian, what was it now? 2019? That's when I realized, "Wow, we really are loved as a band. We actually really mean something to people." Not that I didn't think we meant something, but I think when you're caught up in it and you're getting on with it and it's your life and you're in a band, make records and play gigs…

But when it's taken away — which it was Carey [Lander] dying, me having a child, the band having a hiatus — it was taken away, and I realized how much it actually meant to me. Not that I didn't think it was important to me — it was everything. It was my life. But when it was taken away, and then when we went on that boat, it was the nicest feeling. It was the most inspiring thing that happened in a long, long time. All of a sudden I thought, "Ah, the penny dropped." I thought, "Wow, we're part of people's lives. This is real." That was lovely. That was the inspiration, really, to make this record.

One of the first songs I wrote was "Baby Huey (Hard Times)," and that's a love song to all the people on at the Boaty Weekender. That's a love song to the fans of the band.

I heard such wonderful things about the Boaty Weekender. What was an average day for you like on that boat?

CAMPBELL: I have to say, at first I was quite apprehensive. One, the band hadn't played for ages. It was going to be the first show, and I was quite nervous about feeling claustrophobic or trapped. We've got quite a lot of anxiety, and I worried a bit about that. But in all honesty, without sounding like a massive cheeser, it was one of the most beautiful experiences in my life. It was so lovely to be in such close proximity to the people, the ordinary people that were there to see the bands. There were bands from other places in the world, but it did feel like Glasgow got on a boat. We were on the plane with the Belles and members of Mogwai and Teenage Fanclub, and we're all traveling there, we're all seeing each other in the airport and fighting to get on the [plane] — there were plane delays.

It was a bit of a drama. We were the last on the boat. I was phoning up Stuart Murdoch in the airport going, "Stuart, we're not going to make it. This is a nightmare. We can't do it." Because the logistics of traveling, there were plane delays and cancellations, and so it was very tense to get there. [We were the last] in the boat and people were waiting for us. Everybody clapped, and that was a really nice welcome. It was really cool to walk about, get in a lift, and people [who] look like me, dressed like me, probably [listen to the] same music as me were in there. You realize, "Actually, do you know what? You're not set apart from these people that come to your gigs. You're the same as them. They're the same as you. That's why we're here."

I realized that there were people from all over the world, literally every nook and cranny in the world, who came to see us the day we did the signing. I think we had the longest line in the signing tent, and we waited until every single last person got signed or talked to. There were people from Japan, there were people from Argentina, there were people from everywhere. I was just thinking, "How blessed are we to have reached out to all these people all over the world, and they've all made friends through these bands?" It really restored something. It was very nourishing.

Could you tell me a little bit about the title, Look To The East, Look To The West, and what it means to you as a band?

CAMPBELL: Well, I'm never very good at summarizing these things. But after Carey died, I spent a long time wondering, who am I going to be? What am I now? Who am I? What will I be? What will I do? I'm a mum now. I've got a little kid. My best friend's died. My band is too sad to continue. I don't do any other job, and I was just really searching for answers for a long time. There was a lot of internal dialogue about [what] am I going to do? I guess I was trying to look everywhere around me for answers. Then, of course, the pandemic happened, and then more questions: What's it all about?

What am I going to do? Who am I? What's going on here? I guess it was more of a philosophical thing. Looking to the east, looking [to the west] — it's a bit cheesy. It really resonated with me. There was an attempt to be open-minded to everything and everybody's opinions about everything and try the best I could to be a good person, try to be a better person. It was a lot about me thinking about the past, the present and the future, and the relationship between it.

One day, I was in my car during lockdown. We were allowed to go to the supermarket and all of that, and I was at this junction. There was this group of young Asian kids, university students. In Glasgow, we've got a big population of Asian students, and the city's really changed because of that. It's great — there's a bit of vibrancy or something that maybe I hadn't noticed for a while. I was thinking about this group of young kids, how they're trapped in this country. They can't go home because COVID's happening and they're all standing about catching Pokémon on their phones. It was a little moment where I was saying, "Oh, the world is still turning." Things are going to get better. These kids, they're not indoors just fading. They're just catching Pokémon and they're being hopeful. I should be hopeful.

I thought about Carey. I'll quite often on her birthday, [or] on a Friday or something, do the shopping. I'll pick a bunch of roses up and I'll tell myself I'm buying them for her, because I'd sometimes do that. That lyric is in the song. I thought, "Keep doing that. You have to keep going."

I imagine being a parent will force you to keep moving, too — just seeing to someone's everyday needs.

CAMPBELL: Yeah, my days were busy with [my son]. Thank God for him. I mean, [I'd] have found the strength somewhere. You need to find something. But for me, being a mom and being a parent and having this little kid to look after really helped me both when Carey died and the band stopped being [together]. It was really hard for me. I was really heartbroken. We all were. I found it difficult because I would see Carey every day, even when I was a mom, we'd meet in the park, we'd take Gene for a walk — or every other day, certainly.

That was just something I just could not get my head around. It was just such an everyday loss. Of course, [with] lockdown a bit later on, I'd wonder, "God, what would she make of this?" Part of me would be like, "Oh, she would've loved this because you've just got to stay in the whole day and read books, and she didn't have to be anywhere." Having a kid during in lockdown really helped as well, because you had to get up every morning. You had to be present. You had to be present in the world. You can't hide when you've got a child.

Your new keyboardist, Donna Maciocia — how were you put in touch with her?

CAMPBELL: When we were asked to do the Boaty, we were kind of like, "Okay, so how are we going to do this?" We wanted to do it. My husband, Tim [Davidson], he had worked with Donna. He was like, "I think this person would be a really good fit. You'll really like her. She's a great player, she's very professional. She knows the score." It was quite scary to contemplate getting a session person in.

Anyway, we met and I really immediately loved her. Then she turned up to rehearsals and I loved her even more. She was totally on it, and she brought a lot of joy and a little bit of life to something that needed a little bit of air put into it. We're a bit flat, a bit nervous, a bit scared, a bit apprehensive to do all those first things again, to get in a room to rehearse the songs. Never mind write new music, which is another thing. But yeah, Donna's been a great addition to the group, and she's a very creative person. We quickly knew that we are not replacing Carey. It's just a different chapter, if you like.

We just loved her immediately. She's allowed artistic freedom in the group, and that's lovely as well that we didn't feel so precious, [or like], "Sit there and do what you're told." There's no point. If you've got somebody that's really capable, then you may as well let them get on with it.

After Carey's passing, was there ever a formal conversation among the band members around discontinuing Camera Obscura? Or picking it back up?

CAMPBELL: Not really, to be honest. I think in the aftermath, Carey's wishes were that we would go on and make another record, and we actually talked about that, but I did not have an appetite for that at all — nobody did, really.

I think we're quite a close bunch. We've been around for a long time. We've been in each other's lives for a long time, but there's still difficulties with communication a lot of the time. I think sometimes that can happen. It can happen in families. You have a certain way of communicating. You can often be a bit more open and free with people you don't know that well than [with] people you know. I think we're all quite sensitive to not stepping on each other's toes, not wanting to be the first person that says something like, "Hey, let's make a new record." As if what had happened didn't matter. There's a lot of sensitivity and we're a bit on tenterhooks with each other. I think everybody in the music business was a bit scared to ask us.

Nobody asked us, "Do you want to do this?" Nobody asked us. I think actually what happened was, I made a record with Danny Coughlan and we were asked to do the [Boaty Weekender]. My manager plucked up the courage to tell me that promoter had suggested that the band might want to do it, but they didn't want to ask. And I said, "If they want the band to do the gig, ask the band to do the gig." Maybe we're not as scared as people think.

Yeah, I understand the trepidation. Nobody wants to appear insensitive.

CAMPBELL: People don't know how to talk about death. They're scared. Everybody does it. I do it.

You mentioned the 2018 TracyAnne & Danny album — did working on that fulfill a need to create in the absence of Camera Obscura?

CAMPBELL: Yeah, I mean it did. Dan and I had a lot of fun. We didn't know each other when we first started making music together. He contacted me out the blue and asked if I wanted to do a song. We met [and] we just loved each other. We became instant best friends, and it really helped me get my confidence back. I feel if I hadn't done that thing with Dan, I would never have made another Camera Obscura record. No way. It wouldn't have happened.

I'm really proud of the record that Dan and I made together, and I hope that we'll maybe make another record at some point. Dan's making a solo record… I've heard some of the songs that are absolutely amazing. But yeah, it did fulfill a lot for me. Like I told you before, I was wondering, what am I going to do in this world? Am I going to go and get a real job? What am I going to do? What's going to happen here? What's happening? It saved me a bit.

Out of curiosity, if you could do a non-music-related job, and you didn't have to train or go back to school for it, what would you do?

CAMPBELL: I don't know. I like to cook, so I'd quite like working in a kitchen or something, which I probably romanticize. I imagine it is nicer than it actually is. It'd be a nightmare to do that, really. But I like the idea of doing that. I was thinking fairly recently about [it]. I still think about, "God, do I need to get a real job now? If this doesn't work out, this record, I need to get a real job." That's always in the back of my head. I remembered sometimes you get frustrated being a musician, and I don't really want to go down this road too much, but it's quite difficult to make a living being a musician these days. The music business has changed. You can't rely on record sales, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah.

I thought about how when I was about 19, 20, I went for an interview in the Bank of Scotland to get a job in the bank. I remember saying to the woman, "I don't really want to work in a bank." I said, "I want to be in a band." She was like, at the end, "Right, okay, well, thanks for coming in then. You're not getting a job, you idiot. You just told me you don't want it." So maybe it would be something like that, like an accountant or something really boring and steady. But I'm too old to be trained to be a bloody accountant, so we're stuck.

As a writer witnessing, like, the full-blown collapse of media, I can relate.

CAMPBELL: Of course you do. I get that. Absolutely.

Thinking about the evolving sound of Camera Obscura, Look To The East, Look To The West has more of an overt Nashville-inspired tone. Was this direction something you discussed prior to recording, or did it happen organically in the studio?

CAMPBELL: We've got quite a collective music taste, and I think there's always been slightly a little country tinge in our music, whether it's not being blatantly OTT country, there's always been country influences. I've talked often about my granny's record collection. I used to listen to Tammy Wynette, Patsy Cline, Johnny Cash, and Dolly Parton and lots of American country music when I was a kid. With this record, we went to a place called Rockfield — where Queen made "Bohemian Rhapsody."

It's a famous studio in Monmouthshire, Wales. They opened it in the '60s. It was the first residential studio in the UK, and it was started by these two folksy brothers. A lot of folksy bands used to go there back in the day. People like Black Sabbath made their first record there. It's not really changed. Studio's still the same. The desk is there, everything's exactly the same. It's just a farmhouse. It's totally unpretentious, but it's reeking with nostalgia and music.

Not to go off-topic, but I got a text message from the producer today, Jari [Haapalainen]. He was like, "Oh, I see they chose 'Big Love' [as a single]. To think it almost never made the album. So cool." That was the one song we were like, "What is this song? This is so weird, this song. It's like weird folksy prog rock. God, people are going to think we've lost our minds because we sound like 50-year-olds now. What's going on? We're not hip, we're not cool. The kids are going to be like, 'What is this shit?'"

That song ["Big Love"] was funny. It was a bit controversial in the room when we recorded it. Some people were going, "I hate this. What is this?" We were listening to Waylon Jennings, and we just kind of went for it. I loved this record because I feel like we were a bit more musically liberated. We didn't know what we were doing. We were just kind of trying things out. My husband Tim plays pedal steel guitar, so Jari the producer is like, "Let's get some pedal steel in this record." We did put a lot of pedal steel on the record, actually. We're just making good use of what we had. There's no strings or anything on it this time, really. I want to get back to basics and sound like a band.

How was it reuniting with Jari Haapalainen, who oversaw production on a couple of your most beloved albums, Let's Get Out of This Country and My Maudlin Career?

CAMPBELL: Well, I felt safe. That's what we needed. I'd stayed in touch with Jari over the years. I'd toyed with the idea of making a solo record; I made a lot of demos and I felt very not confident. I wasn't sure what I was going to do with it. I didn't have the confidence to just go and make a solo album. I'd sent Jari some songs—"What do you think of this? Do you want to make a solo record?" And he's like, "Yeah." He's always about the songs. He's like, "If you've got the songs and the songs are good, yeah, we can do anything. We can make a record. We can do anything." He was always like that.

Then, when we went on the Boaty, I started writing like a maniac. I remember [being] in my kitchen, where I'd just stare and sit. My kid would go to school, and I'd have the house for myself, and I'd sit at the kitchen table, get my guitar out and start writing songs — they were just pouring out of me after the Boaty. [I felt] not confident on what to do. Should I tell the band I'm writing songs? What should we do? Should we make a record? I felt like I wanted my hand held a little bit, to be honest, and I felt like he was the person to do it, because he really changed our trajectory when he came along and we made Let's Get Out Of This Country. Things changed for us. We really grew in confidence when we made that record, and it was really down to him.

He managed to somehow take what we knew we had in us and get the best out of us. He got the best out of me at the time, and I felt like I needed that again. We can't go and make a safe little record and be not confident and nervous to communicate with each other. We needed somebody that was going to come into the room and be in charge, and he does that. He's very on top of everything. He's not the kind of producer that sits at the desk with his feet up and doesn't say anything. He takes over. He's so involved, and we wanted him right from the start. I wanted him there holding my hand from the first draft of my first song. It was a nightmare actually, because he was living in Athens at the time, and he was also living in Berlin, and we were having to get him over here.

It [was] during lockdown, flights were getting canceled, and everybody was getting COVID. There were lots of cancellations. It was a hard-fought record to make. As soon as he's in the room, he's so focused and there's no bullshit. He doesn't dress anything up for you if he thinks you're not doing good enough. He just tell you, "That's not a chorus. Go on and get me a chorus. Or, "These lyrics are not so good." He's sensitive. He's not harsh, but he's very truthful and he just wants to do the best job he can do, so he doesn't take any shit from anybody. He is very opinionated; he knows what he wants. He's so focused. We have a tendency to be a bit without direction sometimes.

He's just like, "Right, this is it. I've made the decision and if you want to fight me, you can fight me, and I might let you get your way or I'm going to get my way." It was amazing being with him and he's so interested in the whole thing. He wants to know what the songs are about, what the lyrics are about. He wants to be informed with everything so that he can present the songs in the best, most truthful way. He's amazing. I love him. He drives me nuts. He's quite dismissive sometimes, and sometimes I'm like, "He's totally ignoring me. He's not listening to me." But then at the same time, I just think I'm kind of in awe of him a little bit. I trust him very much. And he was sensitive to the whole thing—making a record without Carey. He loved Carey, and we needed somebody that loved her and understood the difficulty of that.

There's also a continuity with the album's cover — having Fiona Morrison appear on Biggest Bluest Hi-Fi and appearing on this album's cover. That seems to, based on our conversation, connect the past to the present and future.

CAMPBELL: Yeah, that was the idea.

What was the thought behind this album's visual?

CAMPBELL: Well, the band has always been in charge of our own aesthetic. Some people will say things like, "Oh, so did somebody dress you up?" No. Nobody dresses up. We just looked how we looked. We dressed how we dressed back in the day. I felt fairly creative when I was much younger in the sense that I was interested in the aesthetic of the band, but it wasn't contrived. It was just very natural. It was just me and Carey on the cover of our album [Underachievers Please Try Harder] looking how we look, or the band standing beside a wall, looking how they looked. I feel like we're older, and maybe I'm dressing in mum jeans and not really making an effort… and also out of ideas in a way… I don't have the capacity to do all this — making videos and all of that.

I don't mind admitting that my creativity was kind of diminished. I started thinking about what to do with this album cover. It's got to be authentic, and I don't really like the idea of handing it over to a record label, [and they] make their own interpretation. We've never done that. It's never worked in the past, and I didn't want to do that. We managed to get a beautiful day on the West Coast up in Argyll and Bute, and Fiona was quite casually dressed, and my friend Margaret Salmon — she's an American artist, filmmaker — was going to do me a favor and take some photographs. She's snapped some beautiful [photos], we had a beautiful day.

Yeah, it felt sort of linked to the past. I didn't want it to look like bookends. That's our first album, this is our last album. I didn't want to be as blatant as that. There's a continuation in Fiona as she was there when we were 20, and she's here when I'm 50, and she would be there when I'm 60, maybe when I'm 70. Also, thinking a lot about the band's journey, Fiona was there at the beginning. [She] continues to work with the Belles and work with us.

I wondered if you could tell me a little bit about just the process of writing a song like "Sugar Almond," which addresses losing Carey. Was it cathartic? Difficult?

CAMPBELL: It was definitely cathartic. That's what songwriting does for me. That's why I'm going to do it. It's always been that for me. I've maybe not recognized that in the past, but I recognize it now. I know the purpose it has and how it served me.

I wrote "Sugar Almond" a long time ago when Carey passed away, and I didn't do anything with it, and I didn't let anybody hear it. I made the record with Dan, and I didn't feel it was appropriate to put that on, even though I wrote "Alabama" about Carey as well. But "Sugar Almond," it's quite brutal. I'm aware of that. I suppose I felt for a long time, [I was] quite self-conscious about it, or I didn't want to upset anybody.

Then, when I started writing other songs after the Boaty, I started playing songs to Donna because we were doing this songwriting swap thing, this mentorship thing. I was building my confidence up and I let her hear "Sugar Almond." She was saying, "Oh, this song, we've got to finish this song."

It's cathartic and it's brutal. It was one of the songs that flew in the window, so to speak. I didn't really have to work it very hard. I made a little guitar demo, and we hardly played it. Donna made a piano part for it, and it was a song that we did live in the studio late at night. Just me and her and Jari, the boys were all in the mixing room. We did it maybe two times and said, "Look, let's leave it at that. It's not going to improve. It is what it is." So, I hope that it's not too painful for people to hear.

It's hard to imagine how it would be painful to hear… Because it is so beautiful. The language has such honor and love. There's just so much love in it.

CAMPBELL: I hope so. There is love. That's what it was about… I know it'll mean something to our fans as well, and it's not lost on me that that'll be something for them that we'll share.

Look To The East, Look To The West is out 5/3 via Merge.