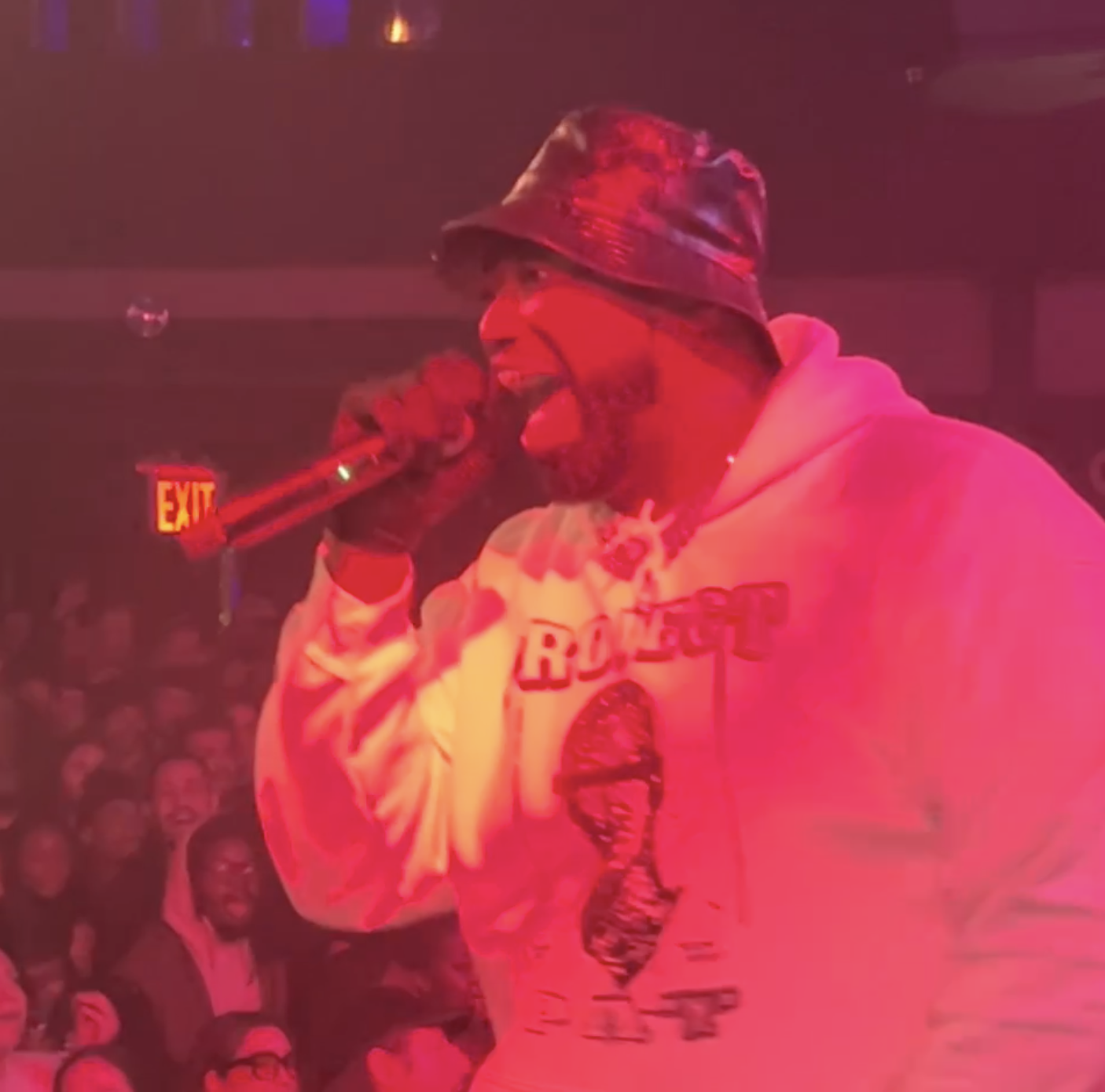

"Shout out to Biggie Smalls! It's Biggie Smalls Day in Brooklyn!" 51-year-old Patrick Earl Houston screams, to my great relief, as he stalks the stage in front of a capacity crowd at Elsewhere in the northeast corner of Brooklyn. It's March 9, at one time the equivalent of a bank holiday in New York — 27 years to the day the city lost Christopher Wallace, its greatest native son — and yet we're hours into a rap show before Project Pat, the North Memphis Tennessee legend, acknowledges the gravity of the evening.

Rain is falling on a Saturday night in Bushwick. Not a cute, light spring mist. It's pissing, to the extent that walking a few blocks — from a Resy-mobbed pub specializing in Korean-inflected bar food to the venue — will leave your jeans and hoodie stuck to your body. Entire corners, stretching into the middle of the street, are covered in great rippling pools of collected rainwater, the product of degraded infrastructure, not elevation. The crowd packed into the great room at Elsewhere is soaked, but excited. They've paid $50 a head to see the great Project Pat at an early show, 30 years into one of the more unlikely, long-lasting careers in rap history.

Pick any moment from the last three decades, and you will hear Pat's influence in many unexpected places, find his fans everywhere, and still come away feeling like he hasn't been properly recognized for his unique contributions to the culture writ large. Don't take my word for it; the great Lawrence Burney did a much better job laying out the history and odd tension of Pat's importance v. his flower count than I can. What is difficult to fathom, but perhaps explains this era of music in this vast and unpredictable digital landscape, is there's a real chance Pat has never been as recognized, and culturally relevant, as he is right now.

Venues like Elsewhere and artists like Pat, in the weird liminal generational space he currently occupies, have made summing up the vibe of a crowd in the time honored, traditional ways music writers used to eat off — when show reviews were prevalent and important articles of culture — difficult to impossible. The once sturdy and reliable shallow signifiers you could glean with a census of hats, coats, kicks, and what songs the crowd is engaging with, is no longer a certain formula. History has ended, God is dead, time is a flat circle. Forty-year-olds look, dress, and act young. Young people look old and can school you on obscure music much older than they are, that they've spent more time with on their phones. To reduce the room to any one type of crowd would be lazy shorthand. They bridge age, race, gender, sexuality, style, and taste.

Some context for those who need it: Project Pat is Juicy J's older brother. For whatever reason, he's never officially been a member of his little brother's amorphous Oscar-winning Memphis collective, Three 6 Mafia, but he's always been affiliated. He's the fifth Beatle, their Cappadonna, and probably the best pound-for-pound rapper in that orbit, with a number ofThree 6 classics he stole to prove it. In the late '90s, running through the aughts, Pat churned out a string of good-to-great solo efforts, arguably finding his apex, in my estimation, with Mista Don't Play: a raw, strange, very funny exhibition of the most original, language-loving and -abusing style I've ever heard, over his brother and DJ Paul's orchestral, grim horrorcore at the peak of their powers. For a time, Pat was a star in the South and a secret handshake for Southern rap fetishests. The New Orleans labels and the Houston Renaissance broke through the mainstream. Pat was a rapper's rapper.

In the years since his prime, Pat's work has been referenced frequently by the generation of rappers raised on it. His voice has been sampled. His beats and melodies have been interpolated, as have his cadences and phrases, both in verse and hook. These tributes culminated in 2021's "Knife Talk," a full-length round of studied, expert Pat karaoke from Drake and 21 Savage, built around a "Feed The Streets" sample so integral to the song that Pat got a feature credit. But the "real" motivation, both for this booking and the recent momentum behind Pat's work, could be from TikTok of all places. In the past few months, several of his songs have suddenly gone viral.

You could argue long before the user-created video-sharing app existed, Pat was an artist uncommonly suited for the medium TikTok has created. He's always rapped in clipped couplets that sound like stitched-together rants, sans millennial pause, or with extreme, affected millennial pause. His bars are nasty, silly, and inventive, saturated with addictive, idiosyncratic line deliveries that stick in your brain forever. In other words, Pat doesn't need a lot of runway to get his ideas across in fun and memorable ways, so he is perfect for an artform rendered primarily in brief snippets.

Take "Good Googly Moogly," Pat's absolutely ridiculous, 18-year-old ass throwing anthem. At some point within the last year, the song became a sound, which has been used hundreds of thousands of times in many instances, with millions of views attached, for what are most often, unsubtly, videos commenting on the thickness of displayed women and men. This was only one of several songs-turned-sounds that have gone viral for Pat in the last few months. At one point he had two nearly 20-year-old songs in the top 10 on Billboard’s TikTok chart. Pat's sudden virality and success are one of the primary examples of the app's random power to inspire a renewed interest in artists born before their times.

"R.I.P. Trouble," DJ Juandeone says from his perch on the stage above the crowd in Bushwick Saturday night, as he warms the crowd up for Pat. The 29-year-old from Connecticut is referring to the Atlanta rapper who was tragically killed in 2022. It is the first acknowledgement of a dead rapper that night. There is good reason for this. I traded texts over the course of an hour with the DJ the day after the show. He expressed what an honor it was for him to DJ a Pat show, how he'd grown up with his music and the impact it made on his taste. When I asked him if he had realized that March 9 was the day Biggie died, he replied, "Noooooo….WELLL WE DID IT IN BROOKLYN….I WISH SOMEONE TOLD ME BEFOREHAND." He wasn't alone. The majority of the crowd — including several significantly younger, very accomplished music industry professionals I attended the show with — weren't aware of the significance of the date until Pat called it out.

This is in no way meant to cast shade on anyone who doesn't have the same gut punch response to March 9 that I do (And really, it's sad and crazy we ever started celebrating the day he died in the first place. As others have pointed out, the holiday should be his May 21 birthday, but reflexively, March 9 still feels like a day worthy of acknowledgement). I'm pretty sure Pat and I were the oldest people in the venue. Juandeone was three years old when Biggie was murdered. The show was 16+, so presumably, the youngest people in the crowd were born 11 years after he passed. To demand reverence for Biggie's death date from this group would be the equivalent of expecting me to hold the day we lost Bobby Darin sacred, but it took being out for me at a rap show in 2024 on the night to realize this. What I found interesting was watching how this crowd received Pat, who is a year younger than Biggie, in the wake of his newfound virality, and wondered what might've been.

I had seen Pat once before, at Santos Party House (R.I.P.) in 2013. This Vice (R.I.P.) show review by Skinny Friedman even then grappled with much of the same wonder I experienced on my way into a sold out Project Pat show in 2024: his longevity and popularity, his maturing into a beloved elder statesman with appeal across decades and audiences. The prime difference from that show, in consideration of this one, wasn't the body count, but the response, which was intense and visceral in 2013. I can't put the blame solely on the crowd. Elsewhere isn't an ideal venue for Pat, elongated and high-ceilinged. He's an artist who needs intimacy and proximity, the sweat and friction of bodies colliding off each other with a punk mix of enthusiasm and hostility. He controls the stage and brings max energy, but any old head who gripes that it's just younger artists that perform with their mics low and the backing vocals high are not to be trusted, were probably not outside in the late '90s and '00s, and have never seen Pat.

As a result of this cocktail, there was what I'd classify as borderline James Blake energy in the room. Juandeone opened with an inspired and eclectic set of club Three 6 remixes and rage beats and Jersey club and grime and trancy shit, all before 9:30 on a Saturday, and there was more interest and movement dedicated to that set than Pat's nearly hourlong performance. Each beat switch, primarily pulled from Mista Don't Play, came with renewed bounce, but quickly returned to the mode most of the room assumed for the entirety of the set: mildly nodding and blinking, smiling silently in place. This is a convenient, lazy metaphor/projection on my part, but you got the impression that if there was an app for reality, the crowd would've swiped up to the next song 15 seconds into each effort, if not the entire performance. It reminded me of rap shows you'd attend in the aughts, when a one-hit wonder came to town, and everyone would show out to suffer through the album cuts for that one big song, then go home. At a certain point, I realized for much of the crowd, that's largely what this performance was.

Because the exception, and "highlight," was when Pat began a medley of the songs that have hit for him on TikTok. An excellent way to gauge how involved a crowd is at a show in 2024 is to clock the number of phones raised in the air recording moment to moment during the performance. For most of the set, there were few. During "Good Googly Moogly" and "Choose U," Pat's recent, app-based hits, there were many. Towards the end of his set, Pat played one of my all time favorites, "Life We Live", and when I wasn't screaming the lyrics at the stage I was looking around, desperate for anyone to enjoy the moment as much as I did. When the show ended there was a type of palpable relief in the herd. The venue needed to get the crowd out quickly because another sold-out show was starting in 30 minutes: DJ Heartstring, Dorian Electra, Esther Cote, Eva Swan Meat, DJ Fuck, etc. I would imagine they were able to start on time. But I enjoyed myself, and to a person, everyone I spoke to claimed to as well. And why not? They got what they came for: a live, extended version of their favorite sound on their favorite app, and their 15-second story or TikTok to prove they were there. They hashtagged #GoodGooglyMoogly and headed to the next bar, or show, or home at a reasonable hour.

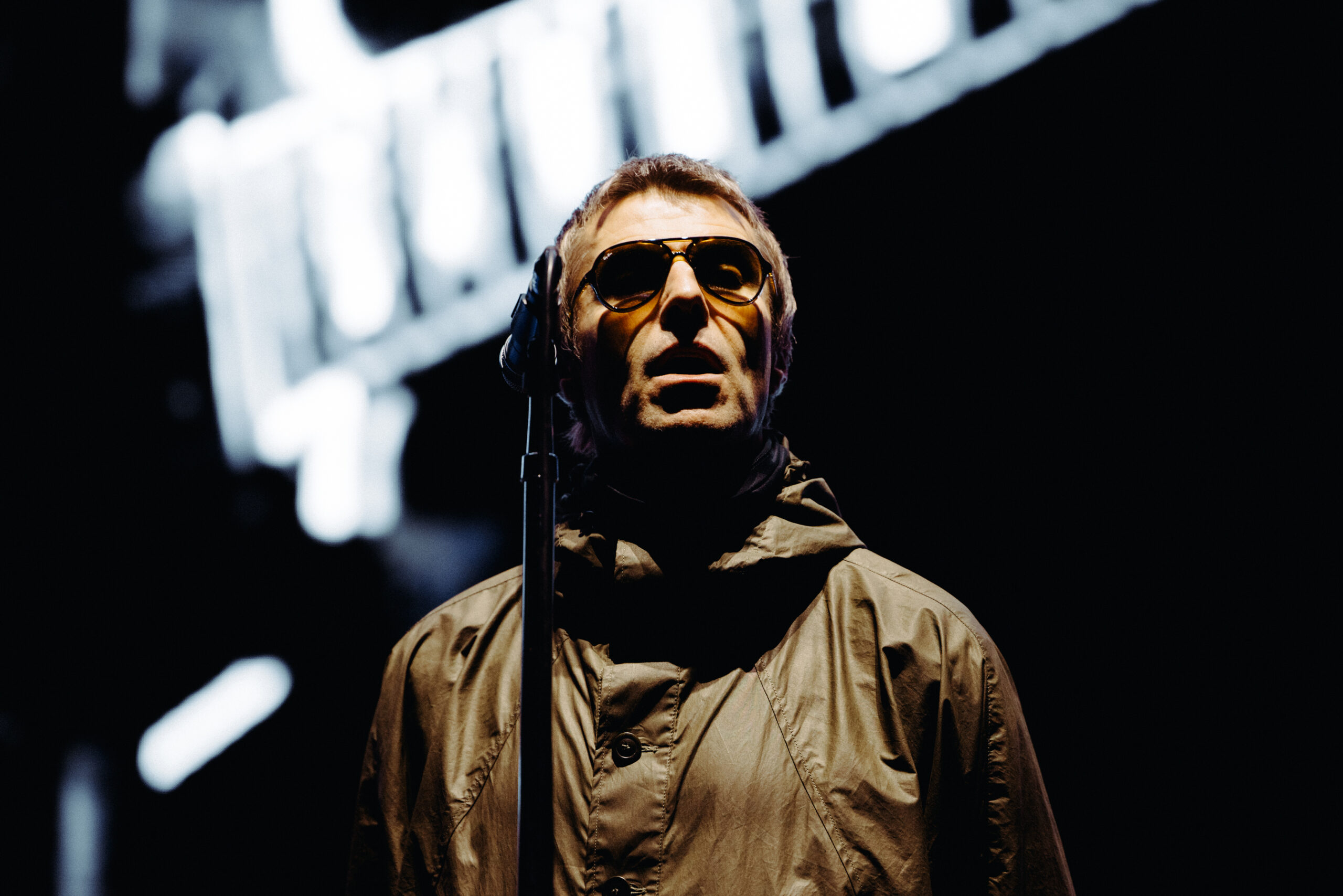

Afterwards, I went to Crown Hill Theater, a newish venue/assembly hall on Nostrand below Atlantic, where André 3000 played the flute recently, but where DJ Spinna was throwing a "houseparty" tribute in Biggie's memory. Due to the weather and a small cover charge, it was a sparsely attended but genuine and fun anti-scene. It was a type of Brooklyn "HIP HOP" crowd I'd expect to find congregating around Fulton at bars like Franks or Night Of The Cookers throughout the aughts and 2010s, an endangered species of uncs in baggy khakis and button downs, and their women in form-fitting dresses, sipping on scotch and sodas or rum and cokes. But also there was a team of break dancers who never got off the floor no matter how many or few people were with them, who might've been able to drink legally but didn't look it. An actual Jungle Brother showed up. Renée from Zhané was there and got on the mic to crush a few songs. There was live keyboard and sax accompaniment in stretches to whatever classics were spinning on the turntables. There was a lot of Biggie, but a lot of "Old School at Noon" staples. Most people acknowledged Big with commemorative T-shirts and sweaters, or Kangols, or Coogis. There were no casuals in attendance. I was reminded of what it's like to stop into most neighborhood churches on a random Sunday in New York. These few fervent, absurd, beautiful people, and their children, huddled below the altar of a dying, revivalist, antiquated faith, too deep in their spirit to notice or care that this version of it is ending.

I think if I was reading this piece, written by someone else, the impression I'd come away with is the writer had set up a dichotomy — a contrast between the packed-out show of checked-out hobbyists disconnected from the artist and much of his art, and the sparsely attended rally of rap acolytes who felt the art deeply — and that the writer believed one experience they had on March 9 was "bad" and the other was "good," so I'd like to at least try to convince you that isn't my intention here. They were different. I certainly was angry, watching what seems to be the beginning of my favorite rapper — who has now been dead several years longer than he lived — being lost to time, as we all will be eventually. But I think this simply is where rap is now, 50 years in. Where it's been for sometime. It's a byproduct of mainstream saturation and digital appropriation. Both were authentic offerings of a modern live rap experience, and both were pleasant experiences I'd recommend to any reader who lives somewhere Project Pat is touring, or where off the beaten path, a DJ is hosting a tribute to the greatest rapper who ever lived, on a night we once all agreed to hold for him.

But what I couldn't stop thinking about after the Pat show is if Biggie were still here today, realistically, where would he exist in culture? Would he be a billionaire legend that impossible-to-please, hotep DSA types accuse of neocon nihilism? Would he be a villain, canceled along with his friend and mentor for discretions against Faith and Kim and God knows who else in the years he would've had to make more mistakes? Would he be a podcast host trading petty, lame shots through various feeds with Joe Budden? Would he have gone off the map years ago, and spent his middle age somewhere in central Jersey, or upstate, or at some villa on a remote private Jamaican beach, basking in the good life out of the public eye with the grandkids he never got to meet?

After some reflection, what I like to believe is maybe he would've ended up like Project Pat: a legend who had an incredible peak run and has settled into comfortable golden years as an artist who still makes a living off his music, seeing generation after generation rediscover and fall in love with him through diverse digital media platforms, celebrated as a king in his hometown, and a bucket list curiosity worth shelling out $50 and coming out of the house for in a hurricane to engage with, even if that engagement is reverently passive. Perhaps of all these realities, this is the best a legacy rapper can hope for in 2024, in our neurodivergent, sped-up culture. At least that's the back nine I would've loved for Big if he had gotten the chance to enjoy one. Here, at the end of the world, who would dare ask for more?

https://twitter.com/p_lyons_/status/1766670491899531574

https://twitter.com/UnholyTriumph/status/1766904907271930083

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!