September 28, 2013

- STAYED AT #1:3 Weeks

In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present. Book Bonus Beat: The Number Ones: Twenty Chart-Topping Hits That Reveal the History of Pop Music.

Every once in a while, a song can sneak up on you, tap you on the shoulder, and blindside you with absolute emotional annihilation. It's not a common thing, and that's probably good. If it happened too often, we'd all be walking around like puddles every day. When it does happen, it's always a surprise. You're driving along, or you're bumming around at work, or you're in a supermarket, and something comes along and turns your soul into smoking wreckage. Those moments are magical. They demand your respect.

One of the best things about those surprise-wallop songs is their ability to cut through context, through bullshit. Context can kill a song. Music is an emotional medium. It builds on our preexisting parasocial relationships with the people who make it. Fandom is complicated, especially these days. When you realize that you like a song, you have to worry about whether admitting to liking that song is the same as endorsing everything that the artist has ever done. (This is admittedly more of a problem to people in my ridiculous profession than to most of you, but I think we all deal with it to some extent.) So when a song has enough power to drown out all the chattering voices that come along with it, you know you're dealing with something special.

When "Wrecking Ball" first blindsided me, I almost resented it. I was in the car by myself, listening to the radio, and I was suddenly plunging into this strange and vulnerable black hole. It was like: Why do I feel like this? Why is a Miley Cyrus song making me feel like this? "Wrecking Ball" had to cut through a lot of context and a lot of bullshit. It came out when Cyrus was at the peak of her pop-cultural infamy, and it weaponized that infamy in some interesting ways. The outrage-baiting music video was the main reason that the song conquered the pop charts as quickly as it did. But I don't think the video or the backstory had anything to do with the way that I felt in the car that day. I felt that way because "Wrecking Ball" is a great fucking song.

Miley Cyrus was only 20 years old when she released "Wrecking Ball," but she was already a show-business survivor, and it felt like she'd been around forever. Cyrus was introduced to the world as a Disney-sitcom version of a pop star, and that had the strange Monkees-style effect of turning her into an actual pop star. For a long time, Cyrus struggled against the Disney-kid image that was the main reason that anyone knew who she was. All through 2013, she used party-kid imagery and calculated outrage to present herself less as an adult, more of an out-of-control wild child. "Wrecking Ball" worked so well, at least in part, because its searing emotional maturity seemed to come out of nowhere. Party kids feel things, too.

Miley Cyrus was almost famous from the very moment of her birth. (When Cyrus was born, the Heights' "How Do You Talk To An Angel," another beneficiary of the Monkees effect, was the #1 song in America.) In 1992, the year of her birth, the best-selling album in America was Some Gave All, the debut LP from her father Billy Ray Cyrus. Billy Ray was a be-mulleted pop-country hunk whose line-dancing novelty anthem "Achy Breaky Heart" drove country purists into frothing rages and still crashed the pop charts in a moment when Garth Brooks was selling more records than anyone else. ("Achy Breaky Heart" peaked at #4. It's a 5. In a strange twist of fate, Billy Ray Cyrus will appear in this column later on.) In the year that he rose to fame, the freshly divorced Billy Ray Cyrus had two different kids with two different women, and he later married Miley's mother Leticia Finley.

Destiny Hope Cyrus was born outside Nashville, and her parents nicknamed her Smiley, which then became Miley. Years later, she legally changed her name to Miley Ray Cyrus. Dolly Parton, a woman who's been in this column several times, is her godmother. Miley was in a show-business family, and a couple of her siblings later made hits of their own. As a kid, Miley went to see Mamma Mia! onstage with her father, and then she immediately told him that she wanted to become an actress. This was a career path available to her. In 2001, Miley's father was playing the title role in Doc, a Christian medical show on the Pax network, and nine-year-old Miley made her acting debut on an episode.

Once she caught the acting bug, Miley Cyrus made all the showbiz-kid moves that her enviable genetic position afforded her. Miley's mother became her manager. She got a small role in the 2003 Tim Burton movie Big Fish. Then, in 2006, 13-year-old Miley moved to Hollywood and became Hannah Montana. The premise of the Disney Channel sitcom Hannah Montana is a neat bit of kiddie fantasy: Miley Stewart is a normal 14-year-old kid from Tennessee who's living in Hollywood. She's got a secret: She's really Hannah Montana, globally beloved pop superstar. Only her family knows her secret identity, and they figure that this is the only way she'll get a chance to grow up healthy and grounded. Everyone else is utterly fooled by the blonde wig that Miley wears when she becomes Hannah.

Before Hannah Montana, Disney had success with pop-adjacent kids' shows like Cheetah Girls and Lizzie McGuire. In 2006, the same year that Hannah Montana debuted, the soundtrack to the Disney Channel movie High School Musical was the biggest-selling album in America. Tons of singers who got famous on Disney shows and movies will eventually appear in this column. But Hannah Montana really represented the apex of the Radio Disney industrial complex. The show was a hit, watched by millions of kids. It wasn't created with Miley Cyrus in mind, but when she came in to audition, they rearranged everything around her. Miley Cyrus could really sing, and she had a bubbly and goofy sense of humor that came off well on camera. Miley's real life story became the backstory of Miley Stewart. Billy Ray Cyrus took the role of Miley's father, and Dolly Parton made regular guest appearances as her godmother.

Naturally, Hannah Montana involved a whole lot of music, and all of it was of the chipper Disney-pop variety. When Miley Cyrus first started releasing music, it wasn't under her own name. Instead, the records were credited to Hannah Montana, the fictional character. The first single of Cyrus' career was the theme song "The Best Of Both Worlds," which peaked at #97. Over the show's four-year run, five Hannah Montana albums came out, and all three of them went multi-platinum. Without significant radio play outside the Radio Disney universe, that Hannah Montana character also landed a bunch of tracks on the Hot 100. Her highest-charting single, 2007's "Nobody's Perfect," peaked at #27.

In between filming seasons of Hannah Montana, Miley Cyrus went on tour, singing songs from the show. With the two-disc 2007 album Meet Miley Cyrus, she sold an idea that was taken straight from the show: One disc from fictional character Hannah Montana and another from actual human Miley Cyrus. She sold out arenas, performing both as Hannah and as herself, and a concert film from that tour grossed $70 million at the box office. The songs that Cyrus released under her own name turned out to be bigger than the Hannah Montana ones. The first official Miley Cyrus single, a fizzy quasi-rock jam called "See You Again," went all the way to #10. (It's a 7.)

Even when she was a baby sitcom star, Miley Cyrus could always sing. Her strange and striking voice must've been a big part of the show's popularity. She was a kid, but she sang like a 38-year-old paralegal who spent her weekends singing in a classic-rock bar band. Her voice was raw and husky and communicative. If you only knew the name from Radio Disney billboards and kiddie magazines on display in Target, then you might be shocked to learn that young Miley Cyrus sounded a whole lot like Pat Benatar. The throaty power of her voice elevated the songs that she was given to sing, and it was hard to say what separated a song like "7 Things," an Avril Lavigne-ish single that went to #9 in 2008, from the songs coming from singers who didn't play pop stars on kids' sitcoms. (Appropriately enough, "7 Things" is another 7.)

"7 Things" came from Breakout, which was marketed as a Miley Cyrus album rather than a Hannah Montana one. Cyrus had a role in writing "7 Things" and a bunch of the other songs on the record. The album went double platinum. That same year, she also had a big voice role in the animated Disney movie Bolt; it's the only one of her non-Hannah Montana acting jobs that's really resonated. Cyrus was still very connected to the role that made her famous. In 2009, a Hannah Montana movie earned $80 million at the domestic box office. "The Climb," a power ballad from that movie's soundtrack, came out under Miley's name rather than Hannah's, and it became her biggest hit yet, reaching #4. (It's an 8.) Cyrus really sang the hell out of that one.

Later that year, Miley Cyrus also sang the hell out of the Dr. Luke track "Party In The USA," which came out on her EP The Time Of Our Lives. That song ostensibly had nothing to do with Hannah Montana, but it essentially tells the story of the show while testifying to the power of pop music. Teenage Miley comes from Nashville to Hollywood, and she's intimidated by all the famous people around her, but she feels right at home when the DJ plays the song that she loves. "Party In The USA" was a smash at the time, and it remains a smash today; my kids love it. The song is now platinum 13 times over, and it was the most-streamed song of Cyrus' career until very recently. It almost became her first #1 hit, too. In the moment, though, "Party In The USA" was one of several great songs to get stuck at #2 behind the Black Eyed Peas behemoth "I Gotta Feeling." ("Party In The USA" is a 9.)

"Party In The USA" was a sign that Miley Cyrus was already a real pop star, rather than just a TV approximation of one. At the time, though, Cyrus was still playing the role, even as she chafed against it. Early on, Cyrus was presented as a clean and friendly alternative to real-life pop stars like her eventual collaborator Britney Spears. Even as the Hannah Montana train kept rolling, though, Cyrus kept getting swept up in minor controversies -- when a few risqué photos came out, for instance, or when someone took a picture of her smoking salvia at a party. Those PR crises were really opportunities for her to switch her image up, to make people think of her as someone other than Hannah Montana.

Outside of the Hannah Montana universe, Miley Cyrus' acting career didn't amount to much, but it did have some ripple effects. In 2010, Cyrus made the Nicholas Sparks adaptation The Last Song. The movie was a critically derided failure, but it introduced Cyrus to Liam Hemsworth, her hunky Australian costar. (He's Thor's brother, but he's not Loki. He's Gale from The Hunger Games.) Cyrus and Hemsworth started a chaotic on-again/off-again relationship that would keep going for many years. That same year, she also released Can't Be Tamed, an album that was explicitly sold as her wild-child record. It wasn't especially convincing, even if Cyrus co-wrote almost all the songs. The album went gold, and its title track peaked at #8. (It's a 5.) But Can't Be Tamed still sold way less than any of Cyrus' previous records. She was finally finishing up her run as Hannah Montana, but the public was having a hard time seeing her as anything else. Something radical had to be done.

Bangerz was something radical. As she became a legal adult, Miley Cyrus was partying harder and costing herself opportunities. She was cast in a voice role in the hit animated movie Hotel Transylvania, for instance, but she lost it after posing for a picture licking a penis-shaped cake that she'd bought for Liam Hemsworth. (The role went instead to Selena Gomez, another Disney-sitcom kid who will eventually appear in this column.) Cyrus cut her hair off and started guesting on club records. She hired a former Britney Spears manager, and she got to working with rap producers. On the album that ultimately became Bangerz, Cyrus' chief collaborator was Mike Will Made-It, an Atlanta trap producer who'd come up making beats for artists like Gucci Mane and Future. There were rumors that she and Mike Will were dating for a minute; I don't know what was going on with those. Cyrus also rapped alongside Wiz Khalifa and Juicy J on Mike Will's 2013 single "23," which was weird. ("23" peaked at #11. Mike Will's work will eventually appear in this column.)

Today, Bangerz is a strange relic, and maybe a problematic one. At the time, the album was framed as Miley Cyrus' hip-hop record. She worked with rappers -- Future, Nelly, Big Sean, French Montana -- and even did a little rapping herself. She also enthusiastically embraced the superficial trappings of Atlanta rap. She wore flashy jewelry and gold fronts. She twerked. She sang over Mike Will's 808 booms and hissing hi-hats. When a rich, born-famous white girl is so quick to identify with Black music that comes from desperation, people are going to react. Bangerz probably wouldn't fly today, and even at the time, plenty of people accused Cyrus of obnoxious, ahistorical appropriation.

But if Miley Cyrus was going to make a white-girl party record in 2013, then rap music had to be involved. This was the era of trap-rave, the moment when EDM producers were fucking around with Atlanta-style drum programming, as on Baauer's "Harlem Shake." The delirious combination of genres on Bangerz -- Atlanta rap, EDM, down-the-middle pop, '80s arena rock, Walmart country -- is a pretty accurate reflection of what would be playing when people of Cyrus' age and demographic were out partying. It's crucial to note that Cyrus is a lot younger than contemporaries like Katy Perry, Lady Gaga, or Kesha. She's not much younger than Taylor Swift, but Swift wasn't trying to make party music at the time. Bangerz is messy, but it reflects a messy culture.

That messiness is on full display on the album's first single. Mike Will co-produced "We Can't Stop," a sort of rap-adjacent mid-tempo dance-pop manifesto about getting fucked up and hooking up with whoever you want. For the video, director Diane Martel went crazy with Terry Richardson-style drug-porn imagery. The song and its campaign were explicitly designed to erase all traces of Hannah Montana, and it was successful at that. "We Can't Stop" was also a huge pop record. Like "Party In The USA" four years earlier, "We Can't Stop" went all the way to #2, its ascent stalled only by the immovable presence of a summer chart juggernaut. In this case, the juggernaut was Robin Thicke's "Blurred Lines."

The last two columns have already included discussions of what happened at the MTV Video Music Awards that August. You don't need another one, do you? By twerking and tongue-waggling her way across the VMA stage, Cyrus dominated cultural conversation in a way she'd never done before. She reduced everyone else onstage with her, including Robin Thicke, to mere props. She annoyed the piss out of a great many people, but she got all the attention that she could've possibly wanted. That very night, Miley Cyrus also released "Wrecking Ball."

Miley Cyrus didn't have anything to do with writing "Wrecking Ball." Neither did Mike Will Made-It. Instead, the song came from a half-dozen industry-insider songwriters. There's no one main auteur behind "Wrecking Ball," but the song's primary driving force is probably Maureen "MoZella" McDonald, a Detroit-born singer-songwriter who was briefly signed to Madonna's Maverick imprint in the early '00s. MoZella was just starting to get big songwriting placements when she went to work on "Wrecking Ball." She was also going through a terrible breakup, and she put that experience into the song.

"Wrecking Ball" started when MoZella got together with two other pro songwriters, Stephan Moccio and Sacha Skarbek, to try to write songs for Beyoncé, someone who's been in this column a bunch of times and who will return. (Coincidentally enough, Beyoncé's new album has a Miley Cyrus duet, and I heard it for the first time when I was working on this column. Writing about Cyrus and hearing her voice suddenly pop up was a slightly trippy experience.) Sacha Skarbek, a classically trained British musician, has already been in this column for co-writing James Blunt's "You're Beautiful." Stephan Moccio is also a classically trained musician. He comes from Ontario, and he got his big break when he co-wrote Céline Dion's 2002 ballad "A New Day Has Come," which peaked at #22.

In a Songfacts interview, Stephan Moccio says that MoZella almost didn't make it to the songwriting session. She'd just called her wedding off, and she was barely holding it together. They wrote the song in a few hours. The next day, they recorded a demo, with MoZella singing. In that demo, you can hear that the song already has a complete structure, but it's a piano ballad. They wanted to pitch the song to Beyoncé, but MoZella knew Miley Cyrus a little bit, and she knew about the public trials of her unstable relationship with Liam Hemsworth. Moccio says, "MoZella wanted to play it for Miley on a Sunday, because she said, 'If I'm going to get Miley's attention, the best way to get Miley's attention is on a Sunday.' I respect that. There is a psychology sometimes about playing a song for an artist at the right time. If you play it at the wrong time, it can be the best song in the world, but it won't be heard because the artist is not receptive to it." That's so weird! I love it!

MoZella must've picked the right day to pitch "Wrecking Ball" because Miley Cyrus loved it. She took the song to her "Party In The USA" collaborator Dr. Luke, who co-produced the track with his regular collaborator Cirkut. As it happens, Luke and Cirkut were also two of the three producers behind Katy Perry's "Roar," the song that "Wrecking Ball" knocked out of the #1 spot. Somewhere in there, the South Korean-born songwriter Kiyanu Kim, who worked under the name David Kim, came in and did some work on "Wrecking Ball"; he also got a songwriting credit. The thing that I really like about the Dr. Luke/Cirkut production is the way it subtly weaponizes the sound that they used on so many overblown EDM-pop tracks in service of this tender, shattered heartbreak ballad. When the "Wrecking Ball" chorus comes in, that's basically a dubstep bass-drop. In this context, it works beautifully.

This is the part where I try to convince you that "Wrecking Ball" is a pop masterpiece, where I explain why and how it fucked me up when I heard it in the car that day. "Wrecking Ball" is written and sung from a wrung-out post-breakup point of view. It's the sound of someone trying to make sense of what just happened -- why this didn't work out, why they feel that way right now. The song's transitions from quiet to loud are abrupt, almost violent, and they mirror extreme mood-swings. Early on, it's all shivery keyboards and indie-girl voice, with Miley Cyrus singing about the mysterious forces that drew these people together in the first place and the devil-may-care way that they threw themselves into the relationship. Then the chorus hits, and the whole world explodes.

It seems way, way too obvious to say that the "Wrecking Ball" chorus comes in like a wrecking ball, but that's the intent. That's why the song plays out the way that it does. Miley Cyrus suddenly goes from sad whisper to thunderblast roar. She's mad and destroyed and wild-eyed and lost in her feelings, and the music responds with the same level of fervor. It's the classic power-ballad format reinvented for a digital era, where catharsis involves sudden eruptions of electronic bass. As the song goes on, old-school power-ballad instrumentation comes in -- real strings, not synthesized ones -- but the flaming-meteor intensity of that chorus remains.

Miley Cyrus didn't actually write "Wrecking Ball," but she owns the song anyway. Nobody could've sung it better. "Wrecking Ball" is where Cyrus summons all the raspy strength in her voice -- the old-school Southern-rock power, the Disney-kid showmanship, the slick country grit that serves as her genetic birthright -- and puts all that shit to work. She sings from the perspective of someone who really wanted this thing to work, who put all of her energy to it. When it falls apart, she's mournful and betrayed. She will always want this person, but she will never have them. She came crashing recklessly into this person's life, thinking she'd change everything, but she found herself destroyed instead. She never wanted to started a war; she just wanted them to let her in. But instead of using force, she guesses that she should've let them win. That's one of the hardest post-breakup epiphanies that you can have: This thing would've been perfect, if only we were both completely different people.

On a sheer pop-song level, "Wrecking Ball" is immaculate. It's got a huge chorus that demands a singalong, whether you're sad or just having fun with it. It's got these sudden switches in intensity, and those translate through the digital compression of the streaming era. You can listen to "Wrecking Ball" on a crappy phone speaker and get something close to the full effect. "Wrecking Ball" feels like a commentary on Miley Cyrus' public life, even if it wasn't written that way. It's got force and power and personality. It's in conversation with the other songs that were on the radio in that moment, but it also stands out from them. It's everything that you could possibly want a pop song to be.

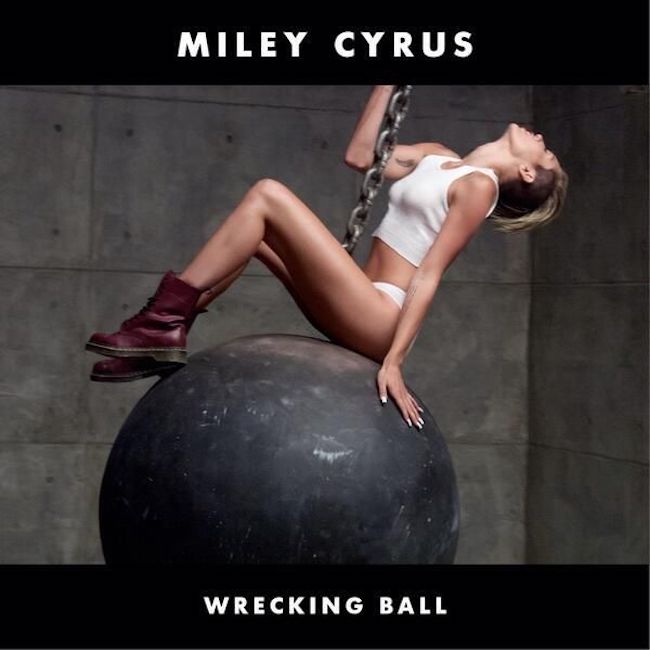

"Wrecking Ball" came out on the same day as the VMAs, and it was already pushing its way up the pop charts before the video arrived, but the video is what hypercharged the song's rise. If there's a disconnect between the frantic twerking of Cyrus' VMA performance and the stark drama of "Wrecking Ball," the video squares the circle and makes it make sense. I'm sorry to report that the "Wrecking Ball" video is directed by Terry Richardson, the big-deal fashion photographer and accused sex offender whose sensibility inspired the videos for both "We Can't Stop" and "Blurred Lines." His "Wrecking Ball" clip is gross, and it's also effective. At least in part, it's effective because it's gross.

The "Wrecking Ball" clip opens with an extreme close-up on Miley Cyrus' face as a single tear slides down her cheek -- a clear echo of Sinéad O'Connor's "Nothing Compares 2 U." Then, it's Cyrus wandering through brutalist architecture, suggestively licking a sledgehammer. When the chorus arrives, Cyrus rides a literal wrecking ball in ecstatic slow motion, and she's butt-naked except for her Doc Martens. The images are all hyper-sexualized, and Cyrus plays in with the porny excess of it all, but she also communicates the hurt of the song. We're watching as a party girl feels the total obliteration of heartbreak. It weaponizes our voyeurism.

The actual Sinéad O'Connor wasn't happy about what Miley Cyrus did with the visual references to her work. In an open letter to Cyrus that she posted in The Guardian, the late O'Connor wrote, "I am extremely concerned for you that those around you have led you to believe, or encouraged you in your own belief, that it is in any way ‘cool’ to be naked and licking sledgehammers in your videos. It is in fact the case that you will obscure your talent by allowing yourself to be pimped, whether its the music business or yourself doing the pimping." Cyrus responded with tweets that made light of O'Connor's mental health problems, and the back-and-forth went on for a little while. The whole episode was ugly.

But the video did what it needed to do. Like the "Blurred Lines" clip before it, "Wrecking Ball" used the novelty of naked people on YouTube to its advantage. In its first day, "Wrecking Ball" got 19 million views, a record at the time. With Billboard factoring YouTube into its methodology, that was enough for "Wrecking Ball" to push "Roar" out of the #1 spot despite only a tiny fraction of the radio plays. The song stayed on top for a couple of weeks before falling back down the charts. In December, though, "Wrecking Ball" returned to #1, mostly because of a viral clip where YouTuber Steve Kardynal parodied the song's video, crawling around in his underwear while on ChatRoulette and recording the delighted reactions of the randos who encountered him there.

"Wrecking Ball" rose to #1 on the back of Miley Cyrus' noisy VMA night and through the sensationalism of its video, but the song has hung around simply by virtue of being great. Last year, "Wrecking Ball" went platinum for the ninth time. It's become a bit of a standard. Sometimes, I really have to dig for Bonus Beats in this column. This was not one of those times. The Bangerz album ultimately went triple platinum, and Cyrus' tour behind the LP was a notorious aesthetic pileup that made a bunch of money. "Adore You," the LP's final single, peaked at #21.

Miley Cyrus returned to the VMAs in 2015, this time as the show's host, and she made a big announcement: Her Bangerz follow-up would be out that very night as a free download. Cyrus mostly recorded the overlong and indulgent Miley Cyrus & Her Dead Petz with the Flaming Lips, and it fucking sucks. Nobody likes it, and the world largely and justifiably treated it as an embarrassment. (The Flaming Lips' only Hot 100 hit, 1994's "She Don't Use Jelly," peaked at #55.) Still, that record worked as proof that Miley Cyrus was a real honest-to-god weirdo. She wasn't faking the funk.

Miley Cyrus & Her Dead Petz seemed like the work of a pop star who was desperate to renounce her pop stardom, but that wasn't really the case. On her 2017 album Younger Now, Cyrus tried to present herself as mature and slightly embarrassed by the whole VMA saga, and she distanced herself from the rap music that she'd sloppily embraced. As a commercial play, it didn't really work. The album stalled out at gold, and lead single "Malibu" peaked at #10. Good song, though. (It's an 8.) Over the next few years, Cyrus became less and less of a pop-chart factor. I really like "Midnight Sky," the lead single from her I'm-a-rocker-now 2020 album Plastic Hearts, but it couldn't get past #14. Most of Cyrus' singles didn't do anywhere near that well.

But Miley Cyrus never became any less culturally present. She kept living her life, and she seemed to have a good time doing it. She came out as pansexual. She married and then divorced Liam Hemsworth. She spent a season as a coach on The Voice. She filmed herself playing shows in her backyard, sometimes bringing along rock-legend types as accessories. She covered a ton of alt-rock classics, up to and including the damn Cocteau Twins, in concert. She also became a dependable presence at things like the Grammys and the SNL 40th-anniversary special -- a seasoned pro who was always happy to show up and sing someone else's classic song.

Too often, pop stars short-circuit when they fade away from the spotlight. They go into seclusion, or they desperately thrash around for another hit, or they somehow do both of those things at the same time. Miley Cyrus didn't do any of that. She just stayed around, radiating slightly daffy good vibes and happily accepting her new role as a show-business pro. Then something unexpected happened: About a decade after "Wrecking Ball," Miley Cyrus released a song that somehow became even more popular. I did not expect the Miley Cyrus comeback to pop off the way that it did. We'll see her in this column again.

GRADE: 10/10

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!

BONUS BEATS: A few days before "Wrecking Ball" ascended to #1, Haim stopped by the BBC Live Lounge to play a slinky version of the song. (London Grammar also did their own "Wrecking Ball" cover in the Live Lounge a couple of months later.) Here's Haim's version:

(Haim don't have any Hot 100 hits of their own, but they guested on Taylor Swift's "No Body, No Crime," which peaked at #34 in 2020.)

BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's Smashing Pumpkins leader Billy Corgan playing a solo-acoustic "Wrecking Ball" cover backstage at The Tonight Show in 2017:

(The Smashing Pumpkins' highest-charting single, 1996's "1979," peaked at #12.)

BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's Brandy, an artist who's been in this column a handful of times, singing a dramatic version of "Wrecking Ball" on a 2021 episode of the TV show Queens:

BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Last year, Miley Cyrus' aforementioned godmother Dolly Parton released her long-promised rock album, and she and Cyrus recorded a duet version of "Wrecking Ball" for it. Before that, they sang "Wrecking Ball" together on Cyrus' New Year's Eve special, combining it with Parton's own "I Will Always Love You." Here's that performance:

BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: I'm about to spoil Strays, the ultra-nasty 2023 comedy where Will Ferrell and Jamie Foxx play the voices of two presumably-CGI dogs. I thought that movie was pretty good, so if you think you might want to see it, stop reading now. The story goes something like this: Ferrell's character Reggie realizes that Will Forte, his owner, is a piece of shit who put him out on the street. Reggie vows that he'll get his revenge by biting Forte's dick off. That's what happens. In the movie's climax, a dog bites Will Forte's dick off while his house burns down and another dog shits on his face, and "Wrecking Ball" soundtracks the scene. I saw this movie in the theater with my son, and we both laughed very hard. Here's the scene in question:

The Number Ones: Twenty Chart-Topping Hits That Reveal The History Of Pop Music is out now on paperback via Hachette Books. I never meant to start a war. I just wanted you to buy the book.