- Jagjaguwar

- 2014

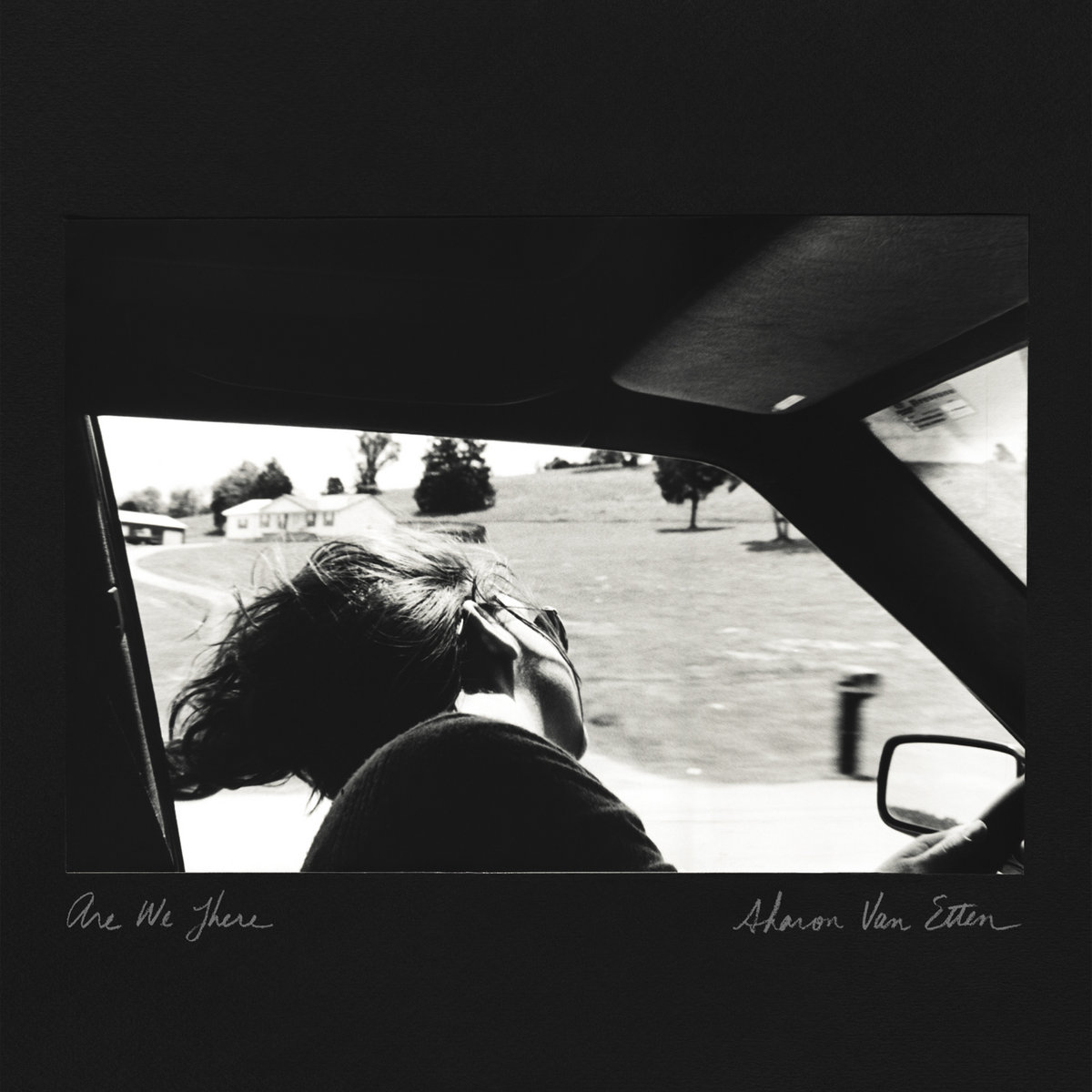

In the spring of 2014, Sharon Van Etten told interviewers again and again that the photograph on the cover of Are We There — her fourth studio album, released 10 years ago this Monday — depicted a woman craning her neck out of a moving vehicle to get a better look at a car crash.

The first time I read an interview with Van Etten that spring, I fundamentally misunderstood what she was saying. I thought she had conceived of the woman pictured on the cover as someone who was, herself, steering head-on into an imminent crash, that we were witnessing the last moment before impact. Looking back, it's not surprising that my mind jumped to that conclusion. I was thinking of almost nothing but the screech of metal on asphalt.

Van Etten's 2009 debut, Because I Was in Love, found her lumped in by critics with other acoustic-guitar-playing female singer-songwriters of the time. Her voice, smooth as glass and often in its highest pitch, fluttered above the plucked guitar notes as she sang about love, loss and pain. The songs are beautiful and ethereal, but to me, they sound like a place for her to hide. She is smothered, almost trapped inside them.

She grew teeth on her 2010 follow-up, Epic, bringing in collaborators in the forms of drum and bass players, as well as brutal, crushingly vivid imagery on the album closer, "Love More": "You chained me like a dog in our room/ I thought that's how it was, I thought that we were fine." Whether the statement was literal or metaphorical doesn't matter. As the kids say, if you know, you know. That was her pact with the listener: She would always be honest, even when the truth was devastating. It built trust.

In 2012, the Aaron Dessner-produced Tramp packed even more of a punch. "That Van Etten has been given the time and space and resources to feel out her path, unhurried by the tyrannous buzz cycle, is both a total luxury, and totally vital," Rachael Maddux wrote in a review for Pitchfork. Mistrust and isolation still permeated all the lyrics, but they were leavened by moments of connection and optimism on songs like "We Are Fine" and "All I Can." She was getting closer to something, and the metatext of her collaboration with Dessner was that she now had an implicit industry blessing -- an outsider no more. The question of Are We There was what she would do with it.

In the spring of 2014, as the first green buds poked their heads out only to be buffeted by fickle cold winds that blew from every direction, I was doing an inventory of myself. I was 25, and I was starting to gain an understanding of the off-kilter moon that ruled the riptides inside me. I was trying to determine which part of me it was that always seemed to be looking for trouble. I was living with three roommates. I was parsing through a meteoric heartbreak of a few years before. I was walking home alone at night, alcohol thrumming through my veins, convinced of my own invincibility. In Van Etten, I saw a kindred spirit: a soft heart drawn irrevocably toward disaster.

There was a boy that spring. He had been visiting the city the summer before, staying with a friend of ours. He walked me home from a party one night and didn't leave until the next morning. We flew back and forth to visit each other, kissed on at the stroke of midnight on New Year's Eve. We broke up, kept talking in a way that had become reflexive. He sent me pictures from the beach where he was spending spring break from law school, silvery crescents of sand and water stretching toward the horizon at sunset. In my memory now, it seems like we were playing with the idea of reconciliation, but who knows if that would have borne out. We thought we had more time. In April of 2014, after talking to him just the previous day, I received a phone call that he was dead.

Whatever it was that compelled me to pull up Are We There, the first Van Etten album I had ever listened to, on the ubiquitous streaming service in the following weeks and press "play" -- whether a nudge from a blog, or a tweet from someone whose taste I trusted -- is lost to me now. I heard the sparse opening piano chords of "Afraid Of Nothing," underpinned by a swelling guitar, and something shook loose inside of me. This was what I knew to be true: I didn't know how to be a woman who was older than 25. I felt so bogged down in grief that I didn't know how I was ever going to manage to turn my face away from the past and attend to what was in front of me. I clung to Are We There like a life raft; like a balm and an instruction manual. I had known loss for most of my life. What I didn't know was how not to be ruled by it, forever bent around the empty space.

Are We There is about liminality, the in-between, the discomfort of not having reached your destination yet. Earlier tracks on the album like "Your Love Is Killing Me" are all muck, all mire; lines like "Break my legs so I won't walk to you/ Cut my tongue so I can't talk to you/ Burn my skin so I can't feel you/ Stab my eyes so I can't see" are some of the most indelible, and violent, Van Etten has ever written. One reviewer called them "knee-buckling." "Our Love" comes in a prettier, major-key package, the introductory notes floating above a gentle electronic beat and wordless vocalizing from Van Etten, but once she starts singing, there are more implications of violence, either physical or mental: "You say I am genuine/ I see your backhand again," she tells us in an angelically high register. "At the bottom of a well/ I'm reliving my own hell." It's not hard to parse that the love between these two people referenced in the song title is a minefield, a constant state of push and pull, of uncertainty. A liminal space if ever there was one.

As a respite from all these bad vibes, Van Etten takes us to the sun-soaked beaches of Tarifa, Spain, on the mid-album track "Tarifa." "I can't remember anything at all," she tells us, and considering the previous devastation she's shared, a bit of sun-induced amnesia honestly feels like a blessing. She's not away from the conflict, not completely -- "Chewed you out, chew me out when I'm stupid," she sings -- but it does feel like a bit of breathing room, a blessedly cool breeze blowing through an open window in a stuffy room.

We're back in the weeds again with the next handful of tracks: "I Love You But I'm Lost," "You Know Me Well," and "Break Me" find Van Etten still at the bottom of the well she references in "Our Love," not making much progress at all in climbing back out. "He's making room for me in the city," she tells us in "Break Me," a line that sounds optimistic enough until she continues, a few verses later, "He can make me/ Move into a city on my knees." In thinking about these lines, I was reminded of the accusations that FKA Twigs leveled against Shia LeBouf in her 2021 lawsuit against him, citing physical and mental abuse. "The whole time I was with him, I could have bought myself a business-flight plane ticket back to my four-story townhouse in Hackney," she told the New York Times. She didn't do it, she said, because "he brought me so low, below myself, that the idea of leaving him and having to work myself back up just seemed impossible." We give the people who hurt us so much power. Taking it back can feel insurmountable, literally paralyzing. By track eight of Are We There, we are rooting so hard for Van Etten to find the strength to leave.

It was his beloved motorcycle that killed him, my not-boyfriend, in a single-vehicle crash on an empty road late at night, only a few miles from his apartment. "I need you to be afraid of nothing," the refrain of Are We There’s first track, was my wish for him, my prayer: that he wasn't scared, even as he drew his last breath by himself on the side of the road.

Grief and heartbreak, although they take similar wrecking balls to one's nervous system, are not quite the same thing. I struggled with the finality of breakups my whole dating life -- to me, only death is the last word. But the solutions, the balms, are similar for each affliction. Even if it's only for five minutes, an hour, a night, you have to give yourself over to small, quotidian pleasures -- I mean really small, as small as you can get. The taste of a drink you enjoy -- coffee, wine, anything -- as the very first sip hits your tongue. The way the light of the setting sun washes the side of a building. Watching a television show that you know will make you laugh so hard that you gasp for breath. This is the practice of lowering the stakes.

This is exactly what Van Etten does on "Every Time The Sun Comes Up," the final track on Are We There. It's the song that cracks the whole thing open. Major-key and unhurried, it has the lazy pace of a Sunday morning. "I wash your dishes, but I shit in your bathroom," she sings, a line that remains her most indelible to this day. "Every time the sun comes up, I'm in trouble." She resigns herself to it, makes a joke out of it, encourages us to laugh, too. It's hard to imagine the hushed woman of Because I Was In Love gaining enough perspective to laugh at herself.

Over the next few years, I would unfurl the rest of Van Etten's discography, spinning Tramp and Epic so frequently that she was my most-listened artist on the ubiquitous streaming platform in 2015, and in the top five the year after. In her songwriting, she sugarcoats nothing, but never denies the places where the light breaks through. She has been my guide, my cult leader, teaching me to survive the unsurvivable.

The legacy of Are We There, 10 years later, is that of a turning point. Van Etten had outgrown a certain version of herself, the person she had been within the confines of the relationship that she ultimately left behind. The person she was at the beginning of Are We There needed to know how far she was from her destination. By the end, she's no longer so pressed. She has the window down and she's dipping her hand through the breeze, leaving all the bad vibes in the rearview mirror. Are we there? It doesn't matter. We're on our way.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!