The least-loved albums by veteran artists tend to find their way, in time, to critical rehabilitation. It’s practically an inevitability, particularly if the artist in question is deemed sufficiently historic. Lou Reed's notorious Metal Machine Music was reviled on its release only to become recontextualized as the urtext of the harsh noise genre. What was once dismissed as kitschy and chintzy on Dylan’s ’80s records became a bedrock of the War On Drugs' acclaimed sound. This website has mounted (partial) defenses of Metallica’s dire St. Anger and Lulu on recent anniversaries, and Pitchfork controversially rescored a bunch of reviews in 2021, elevating onetime duds by Wilco, Daft Punk, and Lana Del Rey to the canon. Stay in the conversation long enough and you might discover that you no longer have any bad albums.

Black Sabbath are about as canonical as it gets, but that hallowed designation has typically only been bestowed upon their early, Ozzy Osbourne-fronted work. "You can only trust yourself and the first six Black Sabbath albums," the famous Henry Rollins quote goes, a count that excludes not only the Ronnie James Dio era but the Ozzy-led Technical Ecstasy and Never Say Die! Tony Iommi may have invented heavy metal with the tritone riff of "Black Sabbath" back in 1970, this line of thinking apparently goes, but he was quickly surpassed. The first two Dio albums, Heaven And Hell and Mob Rules, have since ascended into immortality; they’re not quite as formally groundbreaking as the ’70s work, but the songs are undeniable. (If forced to pick one Black Sabbath to listen to for the rest of my life, I’d unhesitatingly choose Heaven And Hell.) Even 1983’s grimy Born Again, the only Sabbath album to feature Deep Purple vocalist Ian Gillan, has its share of defenders. But one era that almost never gets brought up in discussions of Sabbath’s legacy is the decade they were fronted by Tony Martin, from 1987 to 1997.

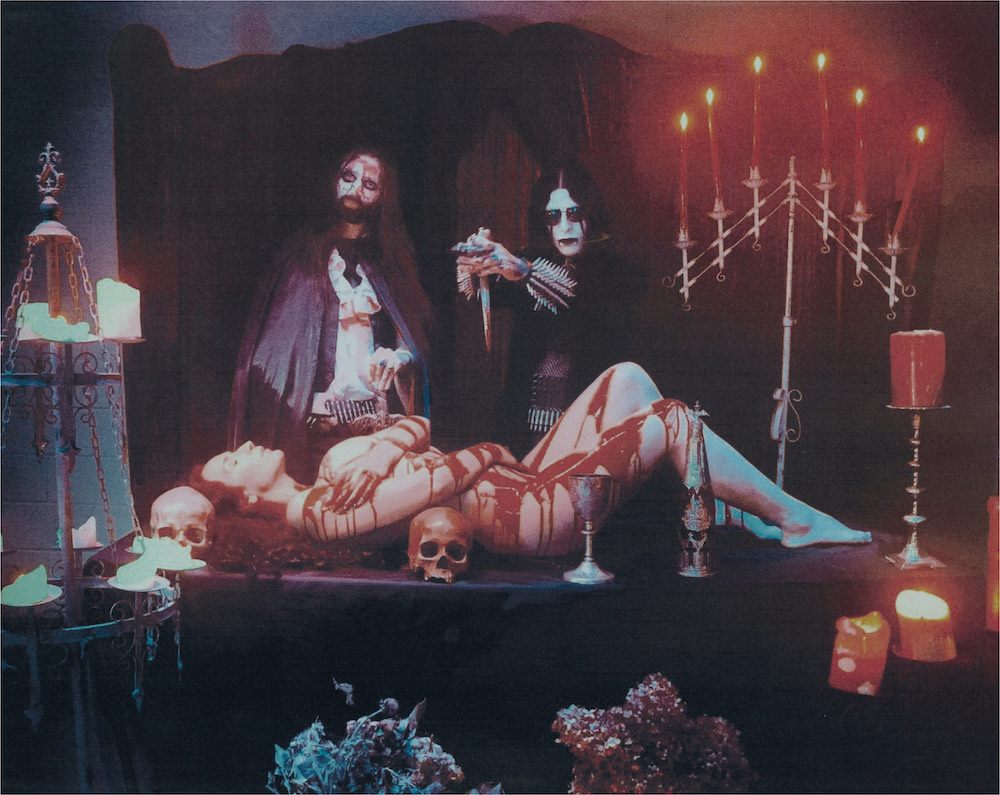

The five albums that Martin sang on – The Eternal Idol, Headless Cross, Tyr, Cross Purposes, and Forbidden – have long been relegated to zealots-only status. "Anything after [Born Again] is recommended only to diehard freaks who can’t go a day without hearing yet another spitfire lick from their master’s Gibson, fans of train wrecks who want to hear The Eternal Idol (one of Iommi’s attempts to cross over into the world of Eighties pop metal), and Otto the bus driver," as the Rolling Stone Record Guide so bluntly put it. Now four of those albums (excluding only The Eternal Idol, for rights reasons) have been compiled into a deluxe box set, the lavish Black Sabbath: Anno Domini 1989-1995. It’s the first time the Martin era has ever been highlighted in a collection like this. Its reappraisal has finally arrived.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=Yyt4coI_0hM /wp:paragraph -->

https://youtube.com/watch?v=I8tsZ0rPBAo /wp:paragraph -->

https://youtube.com/watch?v=Yyt4coI_0hM /wp:paragraph -->

Maybe the Tony Martin era is still only for the “diehard freaks,” like Rolling Stone wrote. For decades, his albums have been the ugly stepchildren of the Sabbath discography. When used CD stores were a thing, they were reliable dollar-bin fodder. As time goes by, though, more and more diehard freaks seem to come out of the woodwork. It’s not unusual for me to get a doom metal promo tagged as “RIYL Tony Martin-era Black Sabbath,” as I did with the French band Ecclesia’s excellent Ecclesia Militans earlier this year. Philly’s Crypt Sermon, critical darlings on the cusp of releasing their third album The Stygian Rose, have absorbed the influence of Headless Cross and Tyr into an expansive epic doom sound. (Though he’s primarily a Dio devotee, their singer Brooks Wilson told Epic Metal Blog in 2020 that “Tony Martin has taught me a lot of ways to expand my range.”) The Tony Martin fans are out here, and if we’re not yet legion, we at least think we’re on the right side of history.

The Martin albums will never be revered the way the Ozzy and Dio records are, and that’s fine. At any rate, the Anno Domini box should give them a chance to step into the sun, to breathe, and to exist on their own terms. Martin and Iommi shot a conversational series of YouTube videos as promo for the box, and they seem prouder than ever of the work they did together. The box set editions make the material sound the best it ever has, with remastering jobs applied to all the records and a full remix of Forbidden, helmed by Iommi. If you haven’t taken the plunge into these records yet, now’s as good a time as ever. If you choose not to, they’ll still be here when you’re ready. Everything gets rehabilitated eventually.

Anno Domini 1989-1995 is out 5/31 via Rhino.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=H9BrcxKdSHM /wp:paragraph -->

https://youtube.com/watch?v=I8tsZ0rPBAo /wp:paragraph -->

Unfortunately, things started to fall apart not long after the release of Cross Purposes. Butler left the band again, and his absence as a songwriting foil to Iommi was acutely felt on 1995’s Forbidden. When people clown on the Tony Martin era of Black Sabbath, they’re usually talking about Forbidden. It’s hard to blame them. The endless years of lineup turmoil had clearly taken their toll on Iommi, and even though the songs take vaguely Sabbath-like shapes, something is off. He just didn’t have the juice. For his part, Martin sounds either tired or bored throughout much of the record. In Iommi’s book, the chapter on Forbidden is called “The one that should have been Forbidden.”

One of the clumsier missteps on Forbidden is also the thing that most directly ties it back to early Sabbath. Ice-T delivers a guest verse on the opening track, “The Illusion Of Power.” It’s not a great verse, and it doesn’t really sound like it belongs on the song. But by reaching beyond the walls of his heavy metal cage to interact with hip-hop, Iommi was tapping into the experimentalism of his early career. As much as anything else, that decision revealed the writing on the wall for that era of Black Sabbath. Martin was out of the band by 1997, clearing the way for Ozzy to rejoin for a series of nostalgia tours and a Rick Rubin-produced album, 13. (Dio also rejoined in 2006, but they called that version of the band Heaven & Hell.) Martin released a passably Sabbathian album called Thorns in 2022, but he hasn’t played with Iommi since ’97.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=Yyt4coI_0hM /wp:paragraph -->

Maybe the Tony Martin era is still only for the “diehard freaks,” like Rolling Stone wrote. For decades, his albums have been the ugly stepchildren of the Sabbath discography. When used CD stores were a thing, they were reliable dollar-bin fodder. As time goes by, though, more and more diehard freaks seem to come out of the woodwork. It’s not unusual for me to get a doom metal promo tagged as “RIYL Tony Martin-era Black Sabbath,” as I did with the French band Ecclesia’s excellent Ecclesia Militans earlier this year. Philly’s Crypt Sermon, critical darlings on the cusp of releasing their third album The Stygian Rose, have absorbed the influence of Headless Cross and Tyr into an expansive epic doom sound. (Though he’s primarily a Dio devotee, their singer Brooks Wilson told Epic Metal Blog in 2020 that “Tony Martin has taught me a lot of ways to expand my range.”) The Tony Martin fans are out here, and if we’re not yet legion, we at least think we’re on the right side of history.

The Martin albums will never be revered the way the Ozzy and Dio records are, and that’s fine. At any rate, the Anno Domini box should give them a chance to step into the sun, to breathe, and to exist on their own terms. Martin and Iommi shot a conversational series of YouTube videos as promo for the box, and they seem prouder than ever of the work they did together. The box set editions make the material sound the best it ever has, with remastering jobs applied to all the records and a full remix of Forbidden, helmed by Iommi. If you haven’t taken the plunge into these records yet, now’s as good a time as ever. If you choose not to, they’ll still be here when you’re ready. Everything gets rehabilitated eventually.

Anno Domini 1989-1995 is out 5/31 via Rhino.