When My Chemical Romance announced their breakup in March 2013, vocalist Gerard Way posted a letter to Twitter, where he said, "it is not a band - it is an idea." The phrase captured the essence of My Chemical Romance. Their music came complete with plot and characters and world-building. Their videos were like movies, their albums so immersive they provided escape.

Or, as Way put it in Tom Bryant's book on MCR, Not The Life It Seems: "I wanted it to be more than a band. It was supposed to be this really intense art project."

Formed in 2001, My Chemical Romance – rounded out by guitarists Ray Toro and Frank Iero, bassist Mikey Way, and then-drummer Matt "Otter" Pelissier– emerged from the competitive New Jersey punk and hardcore scene. Their debut album I Brought You My Bullets, You Brought Me Your Love was rooted in that scene; Geoff Rickly of Thursday produced it, and it came out on local independent label Eyeball Records in 2002. By the time MCR dropped their second album, their reach extended far beyond their home turf.

In August 2003, My Chemical Romance made the move to Reprise Records, a Warner Brothers imprint. They began writing their second record while still on tour in late 2003 and went into the studio in early 2004 with Howard Benson, who had recently produced hits for mainstream hard rock hits like P.O.D.'s "Alive" and Hoobastank's "The Reason." Their sophomore record, Three Cheers For Sweet Revenge, which turns 20 this Saturday, felt like the realization of that idea or art project. "Revenge is really the band," Gerard said in the 2006 documentary Life On The Murder Scene. "Bullets is the band trying to find itself. By the time we hit Revenge we had really become My Chemical Romance."

Their love of horror movies and comic books bled into Revenge’s concept: A man dies and makes a deal with the devil to be reunited with his partner – in exchange for the souls of a thousand evil men. The songs follow a killing spree that takes him to New Orleans ("Give ‘Em Hell, Kid"), a Western-style shoot-out ("Hang ‘Em High") and lands him in jail ("You Know What They Do To Guys Like Us In Prison"). In a 2005 interview, Gerard mentioned that they came up with an ending to the narrative only after the record was finished: "Obviously he kills 999 evil men and then he realizes the last evil man he has to kill is himself."

That's the narrative, but the album was informed by the death of Gerard and Mikey Way's maternal grandmother, Elena Lee Rush, who played piano and helped develop her grandsons' artistic pursuits. She encouraged Gerard to try out for school plays and, with the Ways' grandfather, bought the band their first touring van. She died the night after Gerard and Mikey returned from tour in late 2003, and the opening track, "Helena," is named after her. "Every single emotion you go through when you're grieving is on Revenge," Gerard told Bryant. "When you really break down the record, it's about two little boys losing their grandmother."

The lyrics never shy away from grief or death, instead constantly circling in on it. "I miss you," Gerard cries out on "Cemetery Drive." Both "To The End" and "Helena" have refrains bidding farewell ("say goodbye" and "so long and goodnight," respectively). There are references to resurrection, like the line "I'm coming back from the dead," from "It's Not A Fashion Statement, It's A Deathwish." But ultimately, the lyrics grapple with the finality of death: "They gave us two shots to the back of the head and we're all dead now," Gerard repeats on closing track "I Never Told You What I Do For A Living."

But other themes found their way in. The Used's Bert McCracken – at that point a close friend and drinking buddy of Gerard's, described as a "cellmate" in the album's liner notes – guests on "Prison," inspired by the experiences of touring with other bands. Gerard said the song was, "about that camaraderie and obviously touches on lost masculinity." That exploration of gender and sexuality runs through the record. On "To The End," which loosely adapts William Faulkner's short story "A Rose For Emily," Gerard sings, "He's not around, he's always looking at men." "Give 'Em Hell, Kid" contains the line, "Don't I look pretty walking down the street/ In the best damn dress I own?"

If one of the album's strengths is that it can be read on multiple levels, then what makes it so compelling is that it doesn't require any reading at all. The vocal performances alone are evocative enough to communicate the despair at the center of the album. The bridge of "The Ghost Of You" does the job wordlessly, guitars weaving over the wails. On "Hang 'Em High," Gerard varies the delivery of "She won't stop me, put it down," a little on each repetition, making it almost magnetic. Towards the end of "I Never Told You…" Gerard gives his most over-the-top performance, snarling and bleeding anguish.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!

It's not just the singing. Much of the album's visceral quality comes down to the guitars and the combination of Toro's metal-influenced style and Iero's punk roots. That's what's responsible for so many of Revenge’s show-stopping guitar moments: the lightning-fast solo on "To The End," the intimidatingly intricate parts on "Thank You For The Venom," the two-pronged guitar attack that starts off warbling and erupts to full-on shredding in "Prison."

The pace of the songs also contributes to Revenge’s sense of immediacy. "The Jetset Life Is Gonna Kill You" stretches out into its music-box bridge before snapping into a quicker rhythm. Songs like "Give ‘Em Hell, Kid" feel like a runaway train, speeding up to an explosive point, and creating a sense of urgency that threatens to spiral out of control but never does. The songs are carefully controlled chaos: it feels like they are going to fall apart before they do the exact opposite. In songs like "The Ghost Of You" and "I Never Told You What I Do For A Living" the guitars play the same notes as the vocal melody on the lines "never coming home" and "never again" (respectively), the syncing-up of the parts heightening the desperation and adding to the inescapable, almost obsessive quality to the album.

At the same time, My Chemical Romance weren't afraid to take some pop swings, like on "I'm Not Okay (I Promise)" and "Helena." The album's strong melodies and pop-style choruses were no doubt Benson's influence, and it's potentially why the album had such mass appeal. In the hands of another set of musicians, Revenge might have leaned towards sounding too polished, but it's the harshness of the production and performances that made the material feel so raw.

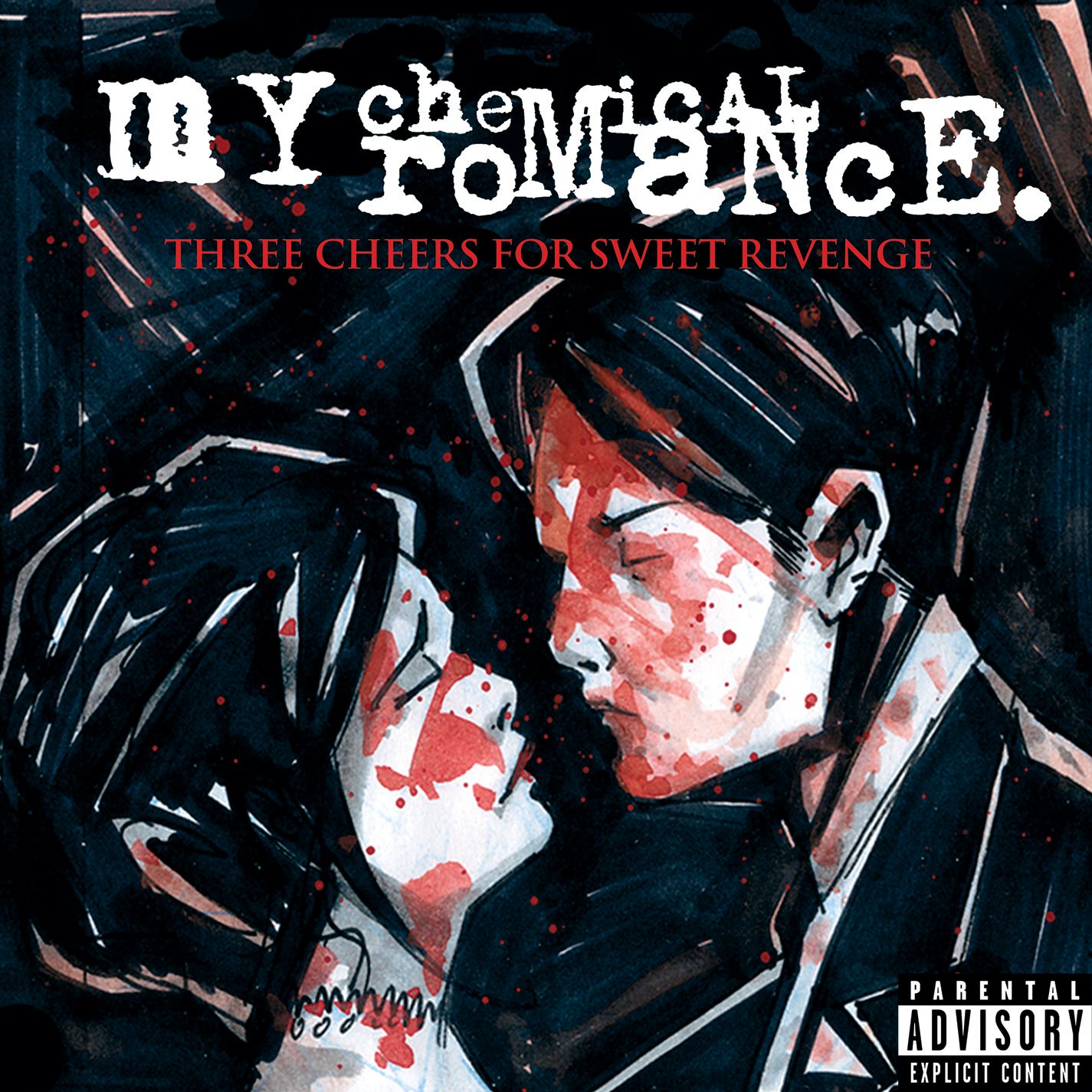

For Revenge, the band adopted a red-and-black aesthetic. The artwork, painted by Gerard and inspired by René Magritte's The Lovers, makes vivid the blood-soaked imagery the lyrics relish in. The band had a specific wardrobe for shows and photoshoots: black suits, red or white button-downs, red ties, and bulletproof vests.

But it was the videos that showed just how far they could take their visuals. "The Ghost Of You" is a World War II drama (I will not spoil it for you here, please just watch the transition from the ballroom to the shores of the battlefield) and cost over a million dollars to make. "I'm Not Okay" is cut to look like a teen movie trailer (Gerard once compared the album title to a movie), and "Helena" takes place at a funeral. Those two videos have become cultural touchstones for emo and pop-punk, depicting two core aspects of the genres: adolescence and the macabre. "Helena" earned four MTV Video Music Award nominations. When Fall Out Boy won the MTV2 award instead, Pete Wentz said "Helena" "should have won."

Revenge was the breakout album for My Chemical Romance. It got the band on MTV's TRL; it landed in the top 30 on the Billboard 200; it's now triple-platinum. It may not have been as commercially successful as their 2006 follow-up The Black Parade, but it cut through quick and deep and certainly paved the way. Even when My Chemical Romance released their fourth and (as yet) final record Danger Days, dressed up in synths and dystopian world-building, you could still hear Revenge’s electrifying DNA underneath it.

Thankfully, in 2024, My Chemical Romance are once again a band, having come back from the dead in 2019. Their own history, the worlds they created, the way their fans talk about them online — it all makes them feel larger than life.

I am not a vengeful person, but Revenge is my favorite album. I still find new things on repeat listens, but a close read is only one way to experience this collection of songs. The record, despite its darkness, is just so much fun. I want to sit down and pick it apart, but I want to jump and shout along to the accelerating "way down" chant from "Cemetery Drive" even more. To me, this is My Chemical Romance's best album, the complete distillation of all they could and would do, and entirely enthralling from start to finish.