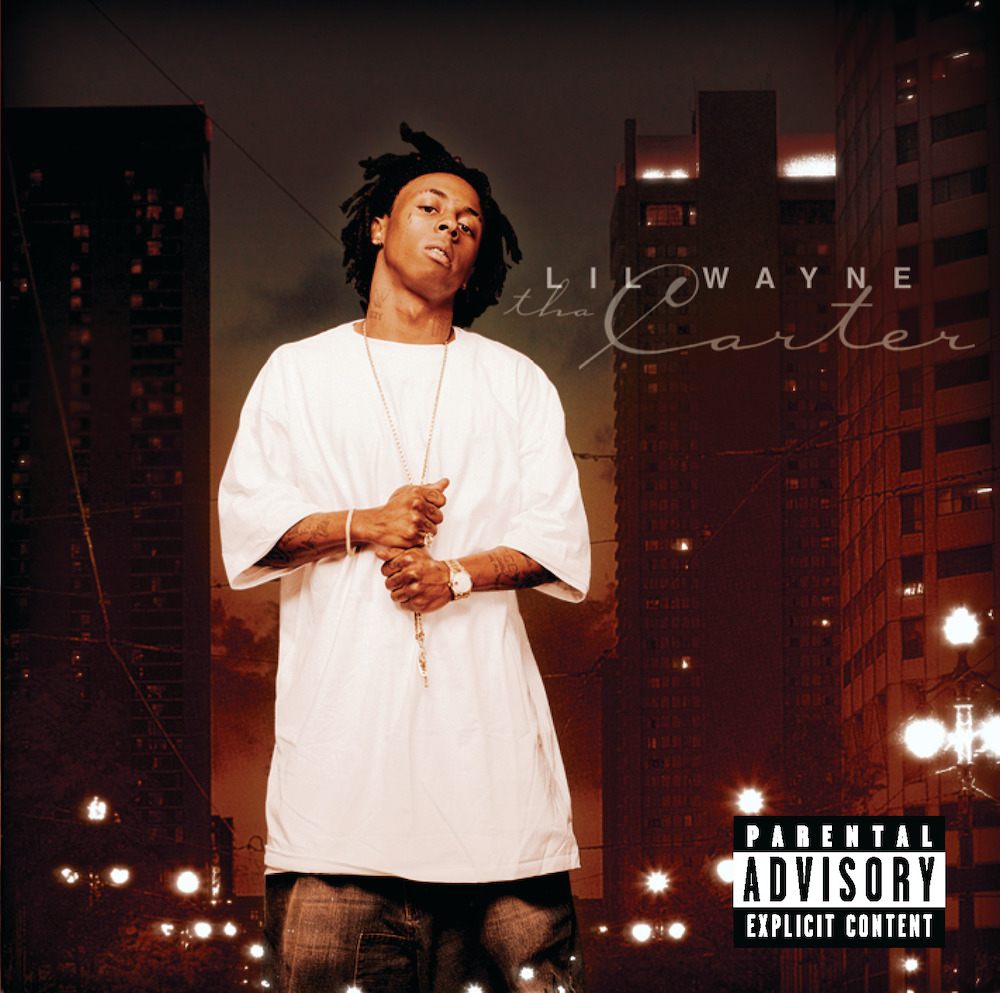

- Cash Money/Universal

- 2004

"Best rapper alive since the best rapper retired." I laughed out loud. Did he really say that? On a single? Lil Wayne? It seemed so far-fetched. Jay-Z's fake retirement had only officially begun a few months earlier, and now this onetime bounce-rap child star was coming for Jay's crown. I couldn't believe the sheer moxie. Shows what I knew. Within a couple of years, Lil Wayne was almost indisputably the best rapper alive. When Jay-Z came out of retirement, Wayne was operating at peak power, and Jay looked lost and sauceless in comparison. If anything, Wayne's boast didn't go far enough.

All rappers should think that they're the best rappers alive, and many of them do. That's the job. If you're turning to rap music for humility, you're doing it wrong. You turn to rap music for lots of reasons, but one of the main ones is the sense of vicarious invulnerability that you can get from hearing a really, really confident person talk their shit. Jay-Z was the world's best rapper, at least in part, because he said and believed that he was the world's best rapper. That's what I didn't get at the time. When Wayne called himself the best rapper alive since the best rapper retired on "Bring It Back," he believed it. Tha Carter, the album that contained "Bring It Back," was where Wayne started to convince the world how right he was.

One of the reasons I laughed was this: I wasn't paying attention. I thought I was paying attention, but Lil Wayne had a whole movement going under the surface. Wayne became a rap star while he was still a baby. He signed to Cash Money Records, then just a regional bounce label, when he was 11 years old. He built a reputation as a local child star before Cash Money signed a major distribution deal and went nationwide. When Wayne got famous, there was a sense of novelty around him. He was a teenage kid who rapped nasty shit alongside the other Hot Boys, but he didn't cuss because his mom wouldn't let him. Cash Money had a huge moment, and Wayne was part of it. His turns on the hits -- "Back That Azz Up," "Bling Bling," "#1 Stunna," "Project Bitch," "I Need A Hot Girl" -- were often short, but they were always memorable. When 17-year-old Wayne released his debut album Tha Block Is Hot, it went platinum right away.

Wayne's next two albums, 2000's Lights Out and 2002's 500 Degreez, didn't sell anywhere near as well. By 2002, the Cash Money exodus had already begun. One by one, Wayne's fellow Hot Boys walked away from Cash Money as Juvenile, BG, and Turk all fell out with their label bosses and slowly faded from relevance. The same summer that Wayne released the first Carter, Juvenile gave Cash Money a #1 pop hit with "Slow Motion," but Juve was already halfway out the door. It didn't feel like a Cash Money victory. The Cash Money era was ending.

At its circa-2000 peak, Cash Money was an army. That was a big part of the appeal. You were listening to this tight crew of hungry young New Orleans hyenas who slid in over each other's verses and only ever rapped on Mannie Fresh's berserk future-bounce production. When the crew fell apart, the effect was ruined. Soon enough, Cash Money was trying to expand into R&B. From original crew, Wayne, his mentor Birdman, and his producer Mannie were the only ones left. Birdman and Mannie rapped, but they weren't really rappers. If someone was going to keep Cash Money alive, it would have to be Lil Wayne. He took the job seriously.

Lil Wayne was always a gifted rapper, but he usually wasn't bodying people on Cash Money posse cuts. Wayne got better, and he did it through sheer practice and repetition -- rapping for hours and hours at a time, getting himself into a strange blackout state where he just couldn't stop. In the early '00s, Wayne started putting out mixtapes with Sqad Up, a crew of his high-school friends. On those tapes, Wayne was the dominant voice, and he used the form to hone his approach. At some point, he stopped writing down lyrics. Those tapes are Wayne doing rap for rap's sake, and the transformation is striking.

The concept behind the 2002 tape SQ7 - 10,000 Bars was that Wayne was finally using up his last rap notebook, spitting those lines over whatever instrumentals his DJ threw him. He just keeps going for 35 minutes in real time, rapping over song transitions and catching the beat on the fly. At the beginning, you can hear Wayne's papers rustling, but it's clear that he's going off the top of his head for much of it. He's in his zone.

That mode wasn't necessarily going to sell records. Outside of the people buying Sqad Up mixtapes in the South, the world didn't know about Wayne's berserker-rage rap-monster mode. We didn't know that he could find the pocket of any beat, stretch his voice into weird shapes, and come up with unpredictable stream-of-consciousness turns of phrase in the moment. We knew the Wayne who made bouncy, funky club songs. That version of Wayne wasn't having the best time in the early '00s. In its original incarnation, Tha Carter was going to be a Sqad Up showcase. But the 2003 single "Get Something" flopped, and Wayne fell out with the other Sqad Up guys. So he ditched the complete album he'd already recorded and restarted Tha Carter from scratch.

Tha Carter, the album that kicked off a towering blockbuster franchise and changed the world's perception of Lil Wayne, turns 20 Saturday. The finished album, the one that Wayne finally released, is miles removed from a peak-era Cash Money record like Tha Block Is Hot. Tha Carter is a document of Wayne left to stand alone, with something to prove. The album has very few guest-verses -- really just a few Birdman cameos and some gleefully unhinged Mannie Fresh intros. Mannie's beats are slower and funkier than the ones he'd been making a few years earlier, and Wayne erupts into the open space that Mannie leaves him. It's Wayne at the very moment when he realized that he could be the best rapper alive, even if the world lagged behind.

In a 2004 IGN interview, Lil Wayne tried to describe the way that he could rap without writing anything down, and I love the imagery of his description:

Let me see if I can explain it. You know how if you have a bad dog and he's just a bad dog, his job is to be bad to anybody around. And if you catch that dog at 3AM in the morning asleep, as soon as he wakes up, he's back barking and trying to bite you 'cause he's a bad dog and that's what he does. Well, rappin' is what I do, so I can be under any [situation] -- I could be dyin', I could be just wakin' up, I could be at my happiest moment, my saddest moment, I could be speechless, I could be voiceless, but I could still rap. That's what I do. So that's why I really don't use the pen and pad, 'cause I kind of feel like when you use the pen and pad, you're readin'. And when you're readin' somethin', man, you're payin' attention to what you're readin' instead of what you're doin'.

It's a different conception of rap. It's existing in the moment, sliding from one idea to the next, challenging yourself. You're not thinking about what you're reading. You're thinking about what you're doing. Or maybe you're just feeling, operating on instinct. On mixtapes, Wayne was free remain in that state for as long as he wanted. Those Sqad Up tapes might be more impressive, on a sheer rap level, than Tha Carter. The tracks on Tha Carter are rigorous and structured, and one of them worked as a full-on mainstream pop crossover. Even so, Tha Carter represents the moment that Wayne figured out how to translate his mixtape flow-state into commercial music.

It's not what Wayne says on Tha Carter. The album has plenty of slick, clever lines, but they don't always look slick and clever on paper. Wayne's best punchlines have as much to do with rhythm and cadence and intonation as the do with wordplay. All through Tha Carter, Wayne is hoarse and playful. He'll stay just behind the beat for a few bars, and then he'll chop against the pocket. He'll find weird little melodies without ever singing. He'll emphasize the wrong syllables, creating new currents in the beat. He sounds so casual, but it's not easy to bounce like that.

You can hear those gifts at work on the big pop hit. Despite the best-rapper-alive declaration, "Bring It Back" only made a minor rap-radio impact, and Tha Carter never charted any higher than #5. After the album had been out for a few months, though, Wayne dropped the irresistible dancefloor call "Go DJ," a song built from a chant that Wayne heard on an old Mannie Fresh tape.

"Go DJ" is one of the all-time great examples of Mannie Fresh's cartoon-funk bounce in action, and Mannie's energy on the intro and hook is infectious. But Wayne carries that energy, too. You can hear sheer linguistic joy in Wayne's verses: "Ayy, it's Cash Money Records, man, a lawless gang/ Put some water on the track, Fresh, for all this flame/ Wear a helmet when you bang it, man, and guard your brain/ 'Cause the flow is spazmatic, what they call insane!" Almost every Wayne line works as a hook. He's having a blast.

"Go DJ" made it all the way to #14 on the Hot 100 -- better than "Back That Azz Up," if not "Slow Motion." It's possible that the single did more for Wayne than the album, at least in the moment. When Tha Carter came out, most mainstream critics ignored it. The album has a lot of the problems that affected B-list rap records in that moment. It's way too long -- 21 tracks, 79 minutes, about as sprawling as a commercial CD could possibly be. There's no sense of construction or motivation, and there are a few clumsy crossover attempts like the Al Green-jacking third single "Earthquake." After a while, those Mannie Fresh beats feel numbing. But even on the deepest of the deep cuts, Wayne never stops going in.

Tha Carter eventually went platinum, but it wasn't a commercial smash. Instead, it was a signal to the world -- a sign that Wayne was really in the game. Wayne named Tha Carter after himself and after the tenement-sized drug spot in New Jack City. But people noticed another connotation to the title. Wayne happened to share a last name with retired best rapper Jay-Z, and Jay noticed what Wayne was doing. I wonder whether Jay helped arrange for Wayne to pop up on Destiny's Child's "Soldier."

"Soldier," a huge pop hit, came out after Tha Carter, and it featured Wayne and T.I., the two ascendant Southern rappers who were vying for next-Jay status. Soon afterward, there were rumors that Jay-Z was trying to poach Wayne from Cash Money. Wayne never signed to Roc-A-Fella, and he later laughed over Jay's small-money offer. But the rumor of a Jay cosign did huge things for Wayne's reputation, and Wayne became president of Cash Money when he renegotiated his deal. The word-of-mouth success of Tha Carter might've also helped feed Wayne's growing confidence. Over the next few years, he would go on an absolutely historic mixtape blitz and transition into a new level of stardom and artistry. He would become the best rapper alive.

Tha Carter feels a little quaint now. It has moments of greatness, but it's not exactly a great Lil Wayne album. Soon after its release, Mannie Fresh would part ways with Cash Money, forcing Wayne to discover the kinds of dramatic beats that fit him best. Wayne continued to improve on a sheer rap level, until nobody could touch him. But Tha Carter was obviously a big moment for Lil Wayne, and he kept coming back to the title. Later Carter albums would become bigger and bigger blockbuster moments. The first entry in the series is a little like the original Fast And The Furious. The charm is evident from the crass, low-budget beginnings. The spectacle would come later.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!