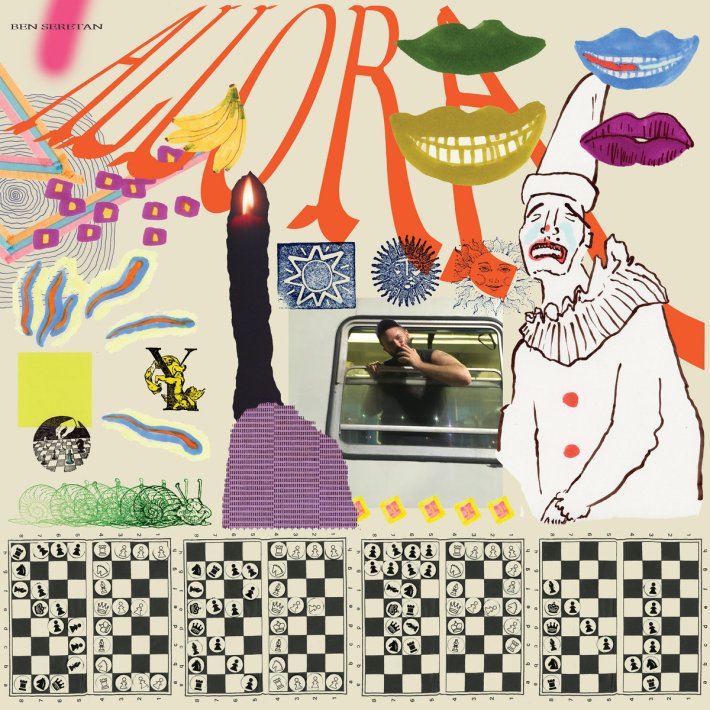

Hear new single "Climb The Ladder" and read our interview about 'Allora,' the New York artist's "insane Italy record" recorded in 2019.

Ben Seretan can't just go around calling Allora his "insane Italy record" without elaborating on both the "insane" and "Italy" part. "It's kind of a long story," he sighs - not the "it's kind of a long story" used as a deflection when the teller knows both they and the listener will be bored out of their minds if recall lasts more than 15 seconds. The earliest iteration of Allora’s electrifying krautrock freakout "New Air" dates back to 2012, when Seretan was just one of many "DIY idiots living in Bushwick" trying to make the scene at 285 Kent and Glasslands. In the time since, there has been unexpected indie fame in the Alpine region of Europe, scammy booking agents, life-altering breakups, devastating deaths, 24-hour ambient albums, a rousing breakthrough released into the gaping maw of early COVID, demolition derbies, dairy farm drag parties, outdoor raves and naked barn dances. Fittingly enough, the story ends in a place called Climax, New York.

Even before our Zoom conversation begins, the last decade of Seretan's personal evolution is condensed into about two seconds: He's wearing a dad hat and a yellow The World Is A Beautiful Place And I Am No Longer Afraid To Die T-shirt in his profile photo before we shift to the present day in his cozy upstate home. "It's just me and the frogs and the rain, so I don't mind the company," he says, quickly shifting to reject the obvious "Brooklyn-Hudson" transplant cliches. "I do like to push against it a little bit because we're here because my partner has a job at SUNY Albany," Seretan explains, while he also holds down a day job at Basilica Hudson. "Other people who move up here with their digital nomad jobs, I mean maybe they're a little less legit, but I'm definitely part of the problem."

While Seretan has put out four releases of raw home recordings since 2020, Allora is framed as the true follow-up to Youth Pastoral. Within a gorgeous and generous melding of freak-folk vocals and up-with-people, orchestral indie rock, Seretan told a story of repression and ecstatic release from crushing, codependent romantic and religious relationships. Through pure word-of-mouth, Youth Pastoral became a breakthrough of sorts, the first time that Seretan had as much heat in America as he did in Italy during the mid-2010s. It was released on February 28, 2020 and my Pitchfork review ran on March 12, the day after COVID-19 was declared a pandemic by the WHO. "There were points during COVID where I was really bitter about the timing, it hurt really bad to feel like, 'Oh, this is the thing that's getting to the people I've been trying to get to, and I'm stuck in my house,'" Seretan admits. "But I felt like the dog who catches the car, it was happening at a time where I was completely unable to fucking handle it."

Though Seretan is in a much better headspace in 2024 and backed by the esteemed, newly relaunched Tiny Engines label, Allora — Italian for "at that time" — doesn't seem intended to take a second (or even third) crack at indie hype. Rather, it's an attempt to create a time capsule for a bizarre set of circumstances in Seretan's life that led to him being stranded in Italy for several weeks - becoming a "very, very minor celebrity" in the country after a few influential bloggers pirated and promoted his self-titled 2014 album but not enough of a celebrity to avoid getting booked for a completely bogus run of shows five years later. With most of the future Allora material already workshopped live, the band found a stone farmhouse studio in a remote part of Venice, run by psych-rock maven Matteo Bordin; Seretan claims it was used as a secret meetinghouse for fascist resistance during the World Wars. For the next three days, the band slept in the studio and made almost no overdubs to the material. Seretan is unsure whether they even got to hear the finished product in Italy.

It's a record of many wonders spanning a vast stretch of personal and sonic upheaval, but it's not a monolith or a self-styled masterpiece, a unified theory of all things Ben Seretan for casual listeners. The wild and wooly guitar jams of "New Air" and "Free" take nearly half of Allora’s run time, balanced out shorter, impressionistic musings on impermanence and death. Somewhere in between is third single "Climb The Ladder," out today, which compresses 20th-anniversary remembrances of Rejoicing In The Hands and Funeral into about three minutes. "The guitar-heavy stuff goes so hard, and then the soft stuff goes really in the other direction, and in my listening, it doesn't flow nicely from piece to pieace," Seretan says. "But looking back, I'm really glad that that's what we captured."

I'm gonna need a little help on the timeline here, because it sounds like Allora was written in 2019, which would be before Youth Pastoral was actually released.

BEN SERETAN: Youth Pastoral took a long time to record. We did the basic tracks in the fall of 2018 with a computer, and then I was just taking my sweet time on it because I had a buddy who had a really nice vocal setup in his apartment and let me record overdubs and vocals on my own schedule. By the time summer 2019 rolled around, Youth Pastoral was already done and getting mastered and amid that process, we got this opportunity to play a festival in Switzerland. That was the beginning of this plan to go out there.

Had you ever toured through Europe before?

SERETAN: Absolutely. I actually have a long history with the nation of Italy and one town in Switzerland, which is just over the border. An album I put out in 2014, my first solo thing properly under my name, was an unexpected minor hit, specifically in Italy. I was doing my thing and then one day, the record I had put out was posted on a really popular BitTorrent website.

I sold a bunch of copies on Bandcamp, and about a week later, I got an email from this guy, Andrea Pomini, who was like, "Hey, man, I downloaded your record illegally. I'm a journalist in Italy. You're going to be featured in my music magazine. Can you answer some questions for me?" And it was one of those things where I was like, "Is this a scam? Who is this man?" He's just a great guy, one of my dear friends. And that led to this cascading thing where he arranged a mass purchase of the LPs so we could send them to a particular record store in Italy and all of his friends bought copies. And then he interviewed me for the magazine. I was in it twice. It was so wild. Eventually he decided to reissue the album on CD on his record label based out of Torino and I did this whirlwind tour where I was solo on the trains of Italy carrying copies of my album and my guitar, like in a laundry cart that he loaned me, going from town to town on the trains for a month. And that was 10 years ago almost to the day.

With most of the album being recorded in 2019, I'm wondering if there was ever a temptation to tinker with the final results.

SERETAN: I'm super fucking hardcore about it because we only had two full days of tracking and I think we just listened to mixes on the third day. We barely had time in the studio, we had to get to the airport. We did no additional overdubs, it's just mixed in the studio in the same space. So I was like, "This is a time capsule." If I fuck with it in any way, it is no longer a compelling document to me.

Most of the songs have only a few lyrics. Were they written in the studio or improvised off the dome?

SERETAN: A little bit of both. It's pretty obvious if you listen, "Small Times" and "Every Morning Is A" were… like, not songs. They were like mumblings and were very much written in the studio. And there were a lot of like arrangement choices made in the studio too, because I really wanted "Climb The Ladder" to be like a 15-minute song. And my band, very smartly said, "Don't do that. Cut it off, just end it abruptly." We haven't talked about it yet, but everything on this record is absolutely, predominantly colored by the fact that our collaborator [Devra Freelander] had died like two weeks before we went into the studio. "Small Times" is not about her directly, but about living in a world without her. "Bend" was a song I had written before that, but the line, "I heard you sing for the last time," had a totally different resonance for that crazy period of mourning that we suddenly found ourselves in.

I appreciate the mention of San Diego in "New Air."

SERETAN: That line is fairly autobiographical, it's from the summer my buddy and I drove from Chicago to San Diego to go on tour with our college band. I grew up in Orange County, I went there on many church trips growing up. I remember my buddy was living at a bungalow by the beach and teaching at UC-San Diego and somehow I drew the [last] straw. There were nine of us on this tour and I slept on the kitchen floor with my face to the tile because that was where it was cool in the apartment. And we definitely had French fry burritos in the morning.

There's obviously a huge element of religious awakening throughout Youth Pastoral and I'm curious about when your leaving the church appears in the overall timeline.

SERETAN: That was a formative thing, my entry to high school. Every time you switch contexts as a young person, you're given an opportunity to reinvent yourself, whether or not you do it consciously or subconsciously. And there was just a lot of turmoil in my surroundings going into high school, and church started failing me in this way that I couldn't get with anymore. I mean, as you were asking the question, the thought really occurred to me, "Am I out of it all the way? What's still in there?" Because it still seems to come up all the time. It's very pertinent and it's where I learned how to play music and specifically where I learned how to play guitar. The real central conceit [on Youth Pastoral] was that I was trying to write from a more adolescent perspective. I've been digging the recent Pedro The Lion albums because they have this "looking back on old California" energy, which I love. But Youth Pastoral came out of leaving a really fucked up and traumatic relationship. I was trying to get out from under that, and I started to see all these parallels between my relationship with the Creator when I was a teenager and my relationship with this person that I was codependent with later in life. "Oh, I'm repeating cycles," the repressed returns; there's all these things on Youth Pastoral that are like the classic joke of how you can make any song Christian by replacing "baby" with "Jesus."

When people leave the church, they have a tendency to seek out other forms of spirituality or connection to fill that void. What has your path been?

SERETAN: I mean, the first track on Youth Pastoral is pretty explicitly about the ecstasy and corporeal joy that I was finding on New York City's finest dance floors at the time. And I feel very much like a late bloomer in terms of the joy of one's body, however you want to interpret that. Following this traumatic breakup that made me question everything about my existence and my relation to the Creator and everything, I got really into running on the Youth Pastoral songs. I'm still really fucking hooked on it, I just like to be in a crowd of people in devotional energy towards a thing. And I found that more readily in dance clubs than I was finding it in indie rock spaces at the time. That is available for certain inspiring performers, but they have a lot of tricks at the club to make you feel like you're having a spiritual experience. That's the high that I'm chasing, I feel like I was freshly, fully realizing how beautiful and breathtaking being in a body could be. The first time I ran, I ran a 5K. And I am a deeply unathletic person. But I ran a thousand miles of cardio in 2018 and kept a spreadsheet and I tracked it and everything. I also lost like 65 pounds that year and was partying really hard. It was totally the exorcism that I needed, but I don't think my body is supposed to do that. The athleticism and the brawniness and the sweatiness, I think that's where my head was at. When I hear Allora now, the sweatiness is present to me.

On that note, the lyrics of "Jubilation Blues" sound like the most tied to the themes of Youth Pastoral. When you sing about watching someone "crushing can after can of Miller High Life" while dancing, would that person possibly hear it today and know it's about them?

SERETAN: No, no, no, they have no fucking clue who I am. I was a total interloper and wrote that song through really wild circumstances. I got invited to a summer solstice party at a hip alternative farm outside of Durham, North Carolina on my first night in town for this residency I was doing. I didn't know who was going to be playing and it turned out to be the new Nathan Bowles trio. It was like, "Oh, a musician I've always wanted to see play is now here, and I'm nude on a fucking Slip 'N Slide that they built."

It's really heartening to see that experiences like this are possible when the headspace of America, on a day-to-day basis, just seems increasingly dark and grim.

SERETAN: I mean, the systems of our nation are indiscriminately horrible, but they're still made of individual actors at the end of the day. And every person out there has a little bit of a freak that they need to take on a walk every once in a while.

Have you ever served as a guide for a fellow "late bloomer"?

SERETAN: I would not characterize my partner as a late bloomer in any way. However, I do go to this festival called Sustain-Release. It's kind of a notorious techno festival in the woods and in order to go, somebody who has been before has to buy your ticket. And so I was able to kind of draw her into that world of techno and camo pants. It takes place at an actual summer camp, and it has this really surreal vibe, and that has been an energy that we've maintained throughout the course.

You've made your ambient records, so I have to ask if there's a techno one on the way.

SERETAN: Not yet. I have a weekly newsletter thing, and there's some definite techno bangers in there, kinda. But it's still forthcoming.

Since Allora was more or less finished by the time Youth Pastoral came out, I imagine you've got another rock record already in the can?

SERETAN: I do not. I've been really trying to figure out what it means for me to play guitar. I haven't really quite gotten there yet. In a similar way that I can never fully get out of the influence of the church on all aspects of my life, I don't think I'll ever get out of being 13, picking up a guitar for the first time, watching Jimmy Eat World play on MTV and being like, "I want to do that." Some part of me is always like, "That would be cool," but I like my life now in a way that I can't remember liking when I was an adult. I like where I live. I often like what I do on a day-to-day basis. My partner and I are in a great place. And I don't really want to blow up my life in that way.

I used to really yearn for the music I was working on to hit me like a lightning bolt and turn me into something else. Every time I put out any kind of recording for the first 10 years of my life doing this, I would always have that hope of, "This is the thing that's gonna change it all." But even if everything changed, it's still that classic idea of, "If you're depressed and you travel, you're just depressed in another country." I feel like I've come to a place now where I'm just very open to receiving what's available and not super bummed out when I don't get other opportunities or things don't resonate in the way that I think they should or whatever. I especially realized during COVID that everything I value in my life has some connection to my having played music a lot. Pretty much every single friend I know, my job now, even my partner - my departed collaborator set us up. Everything I cherish in this life comes from playing music, so I'll just keep doing that.

Allora is out 7/26 on Tiny Engines.