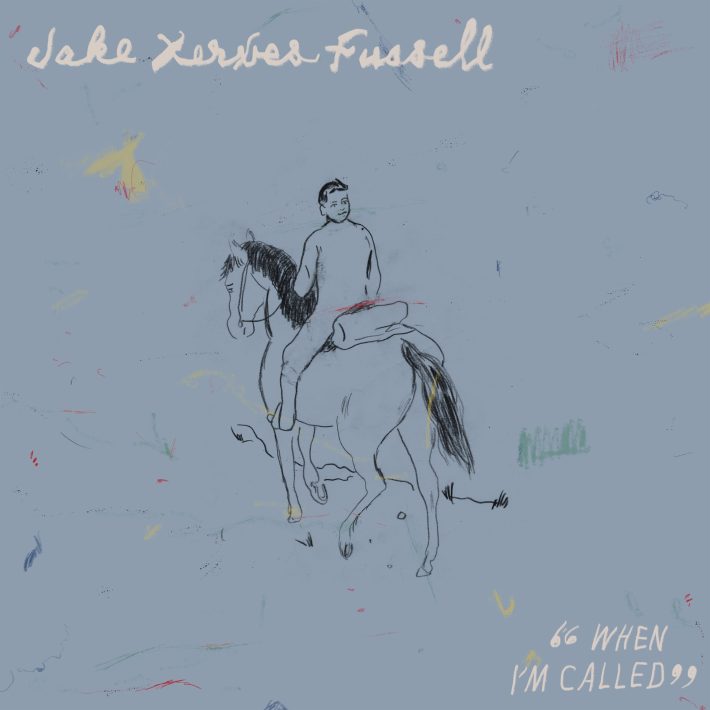

When I'm Called is Jake Xerxes Fussell's fifth album, but it exists in a stream of musical consciousness that began practically with his birth. Raised by folklorist parents in Columbus, Georgia, the singer and guitarist was inculcated in a social circle that included luminaries like George Mitchell and Art Rosenbaum, the latter of whom took a young Fussell under his wing. Traditional music, folk art, field recording, local history — all were a routine part of his upbringing, as ordinary as little-league baseball or summer camp. "My parents never forced any of that stuff on me," Fussell is quick to note. "I was just exposed to it."

Even so, that exposure turned into obsession, and Fussell was soon spending as much time studying the folk canon as he was learning to play it himself. He trained with Henry Parker and Rick Edwards, a couple of older musicians from just across the Chattahoochee River, in Phenix City, Alabama. Parker and Edwards had played under Jimmie Tarlton, half of the late '20s country music duo Darby & Tarlton. Fussell learned fingerpicking – still a hallmark of his style – from Billy Winn, a newspaper editor and amateur Piedmont blues guitarist. By 13, he had his first paying gig, playing upright bass with a bluegrass band on the invitation of his middle school music teacher, David Seckinger. His years spent at the feet of those largely unknown masters were all about building a sturdy foundation.

"As I got older, I became a little bit more adventurous with arrangements and things, and maybe taking more liberty," he says. "[But] in order to break the rules, you have to know the form first. Not that I really see what I do as breaking any kind of rules, but I think in order to explore real deeply, you have to have a fundamental understanding of how the songs work. I was going through all that when I was a teenager and in my early 20s, really trying to learn those forms well."

Over time, Fussell's process has become one of reinterpretation and, when necessary, reinvention. Apart from a trio of original instrumentals that appeared on 2022's Good And Green Again, his songs all trace their origins to some extant primary source, be it a traditional ballad, a sea shanty, or a bit of found text. (One of his finest tunes, the wry "Washington," draws its lyrics from an embroidered wool rug.) What makes his records so exciting is hearing how he synthesizes his wide-ranging source material with his own musical sensibility, and increasingly, with his own autobiography.

When I'm Called revives the past, vividly and to edifying effect, but it also reveals a lot about Fussell's present. More than half of the selections appear on field recordings taken by Rosenbaum, who remained a mentor to Fussell until his death in 2022. Singing these songs became an unwitting purging of grief, and When I'm Called, in turn, became "an Art Rosenbaum record."

But the student has long since stepped out from his late teacher's shadow. In addition to being an accomplished singer, player, and arranger, Fussell has also become a living repository of folklore and traditional music in his own right. I've never had so many tabs open while transcribing an interview in my life; each name mentioned below opens a rabbit hole well worth falling down. (Fussell's cultural knowledge also extends far beyond folk music: We riffed at length about Tommy Boy, the 1995 Chris Farley comedy, because of a gag where Farley confuses my hometown of Columbus, Ohio with Fussell's Columbus, Georgia.) Below, we dive into the story behind every song on When I'm Called. Our conversation has been lightly edited for clarity.

1. "Andy"

This song is in Les Blank's documentary, The Maestro, on Gerry Gaxiola. Is that where you first encountered the song?

JAKE XERXES FUSSELL: Yeah. Have you seen that documentary?

Yeah, it's terrific.

FUSSELL: Yeah, I knew this song for a long time, and I didn't really think about playing it. I just kind of had it kicking around in my head. I knew the Maestro a little bit when I lived in California in the early 2000s for a couple years. I knew him through knowing Les Blank, and I just liked that song. It was interesting to me. I recorded it a while back, just a little demo tape, and thought, "Well, that could be kind of interesting to do." It's just in an AAB blues form, so I stayed pretty faithful to it. But he's such an interesting artist. I haven't communicated with him in a while, but I hope he likes my version of it.

He'll probably hear it. He's lurking in the Letterboxd comments on the documentary, replying to people.

FUSSELL: Really! [laughs] Yeah, that sounds right. He's a funny character. I mean, that documentary is so great. He grew up in Berkeley in the '50s and '60s, and he went to high school with the Fogerty brothers, and I think he was instrumental in helping them name Creedence Clearwater Revival. But he also took a picture of them eating at Taco Bell in the mid-'60s, before they were a band. It's a really funny photograph. Creedence Clearwater Revival eating at Taco Bell. I think it might have been one of the original Taco Bells. But yeah, [the Maestro] made all these tapes that he self-recorded and self-released. And at one point, he gave me a bunch of them, around 2001. I have a few of them, and I think the song is on one of those. I'm sure it is, because I had to go back and listen to it when I was trying to get the lyrics right. He's written quite a few songs that are really interesting.

The context of the "Andy" song is that he was carrying on this one-sided feud with Andy Warhol, and this song was part of his campaign to call him out and make him come to his arts festival, Maestro Day. And of course, Warhol passed away, and probably didn't know that the Maestro existed.

FUSSELL: No, I don't think he knew that the Maestro existed. But I think had he lived, he would be a fan.

How much did you buy that the Maestro hated Warhol? Because in the film, he sets him up as everything that's wrong with the art world, and sets himself in diametric opposition.

FUSSELL: It's hard to tell. He does take some of that stuff pretty seriously. I actually kind of engaged in an argument with him one time about Picasso, because he has this real gripe about Picasso. But he's also a fan, and you can kind of see Picasso in his work a little bit, like everybody who lived in the 20th century. Yeah, I don't know. It's hard for me to tell. I think some of it also is in the cinematic tradition of the gunfight. I think he likes that sort of drama.

Yeah, he wanted to call him out at high noon.

FUSSELL: Yeah, exactly, and he's playing a character. That was one of the funny things about his and Les Blank's relationship, I think, is that [the Maestro] was often kind of directing scenes, and was very aware of himself as a character on film, even though it was documentary.

As far as selecting the song, it's an example of a song that you can trace to a single composer. What's interesting about that for you, as opposed to pulling from a folk tradition where it's a little harder to trace?

FUSSELL: I do sometimes play songs written by other people. Covers that aren't part of the folk canon. I do that plenty in my shows when I play. Maybe one or two songs per show might be one of those. Sometimes I'll do an Arthur Russell song, or Nick Lowe. It has to feel right to do it. Because there's plenty of songs out there that I love, but then it's hard for me to get into the thing as the singer. If it ever feels like I'm playing a character, if it feels like my voice is something that it's not, I tend to back away. So it has to feel right on some sort of emotional level. And a lot of times that has to do with the way my voice feels, and it might have something more to do with melody. I don't really know. But it is kind of an intuitive thing, choosing what songs. I say intuitive, but you're led to things because of all kinds of other stuff. Who you are culturally, and what you're exposed to, and what you might be drawn to because of where you live and who you hang out with and what your class is, and all that sort of stuff. Your exposure is not totally pre-determined by those things, but it's largely influenced by those things.

2. "Cuckoo!"

I think the big thing that stands out in contrast to "Andy" is the arrangement. It's a lot bigger. You introduce a lot of the ensemble that plays on this record on that song. How'd you put together this group of musicians?

FUSSELL: I knew I wanted to work with Jim Elkington again, because I'd been so pleased with working with him before, on my last record. We get along really well, and he's really easy for me to work with, and is also open to all sorts of ideas. I really like working with him. He understands the folk music world, because he's a part of that as a fingerpicker guy and is really schooled in all this Britfolk stuff. But he also has a past in Chicago with experimental post-rock stuff. He plays with Tortoise sometimes, but is also an extended member of the Wilco family. But he also grew up in England in the '80s, so he knows a lot of new wave and Britpop stuff that I don't know much about, but I really like. So I guess that's one thing that I like about him, is that he's not solidly in any one school. I think that's helpful in a producer. Maybe not if I was trying to do a ragtime record, and I really wanted a ragtime producer. But he's open to a lot of different ideas about arrangement and stuff like that.

The way I put this group together was really just people whose playing I liked. I tried to stay open about it. I reached out to Robin Holcomb on a whim just because I was a fan of hers. I've still never met her, so we overdubbed that. But I've been listening to her records a lot the last few years. Joan Shelley is an old friend of mine, so that made sense to ask her. Ben Whitely, who plays bass, I've gotten to know him a good bit in the past few years because he plays with the Weather Station. I've known Tamara [Lindeman] for several years because we used to be on the same label. And we're also both on Fat Possum now. So I'd known her and gotten to know Ben through her, from playing in Toronto and running into each other at festivals and things. Joe Westerlund is a guy around here [in North Carolina, where Fussell now lives], a really great drummer and percussionist. It really just came together with who was available and whose music I really liked. It's a good band.

A few of the people who are doing strings and horns and stuff like that, I don't really know those people as well, because they're Jim's people in Chicago who we hired to do that kind of stuff. So I don't know them as well, but I have met them. Anna Jacobsen does some horns, and she did on the last record as well. Blake Mills I met three or four years ago when I was touring and went through LA. I got to be friendly with him, sort of long-distance friendly, and then we've gotten together a few times and played. I don't know him super well, but we've become friendly. Really great guitar player.

The "Cuckoo!" lyric comes from the same writer as "Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star," which I thought was fascinating.

FUSSELL: Yeah, Jane Taylor. It's funny, that's kind of a complicated song history, because it's really from Benjamin Britten, the 20th century English composer. This was from early in his career, I think in the early or mid '30s. He was teaching some schoolchildren. His brother was the headmaster of this children's school in Wales, and he was arranging folksongs for a choral class, and this was one of them. But the text all came from one or two books edited by this English poet, Walter de la Mare. I've looked for those books, and some of them are traditional songs, and some of them are things that have kind of become traditional, but they were really written in the 1700s by specific poets. I think that was one of them, was this Jane Taylor thing called "Cuckoo!" But of course, there's all these old cuckoo songs. I think she probably was aware of that, even though she was living in the late 17- and early 1800s. As an English poet, I think she was probably aware that there was this family of songs about cuckoos. But it's an unusual one, in that it's sung from the point of view of the bird. I just liked that one, and I'd heard Benjamin Britten's arrangement of that, and thought it was beautiful. Both of these, that first song and "Cuckoo!", were just kind of milling around for a while before I even started to play them. They were just songs I had in my head all the time.

3. "Leaving Here, Don't Know Where I'm Going"

We've got to bring Art Rosenbaum in at this point. You learned this one from him, right?

FUSSELL: That's right. I did. He recorded Joe Rakestraw, who was a great fiddler, guitar player, and singer from Athens, Georgia. The recording does appear on that Folk Visions And Voices anthology that Art and Margo, his wife, released on Folkways in the early '80s. But also, over the years, whenever Art and I would get together, we'd play songs, and I remember Art would play this one on the fiddle and I'd play guitar. His arrangement was more straightforward, like Joe Rakestraw's. Not quite as emotive, or something, as my version. I kind of messed with it a little bit. But that was a tune I associated with him.

This thing happens where every time I make a record, I don't set out to have any kind of theme or anything. I never thought, like, "This is gonna be my record about climate change." Even though I appreciate when people do that. I've never had that kind of thing before. Maybe I will someday, with a really thematic record. It might be interesting to do that. But what happens is always I just throw a bunch of songs together that I've been working on lately and that I think might be interesting together. And then, after I've done that, and I'm putting all these sources together for the liner notes for the back of the record, I start to realize, "Oh, wait. There is sort of a theme here that I didn't realize." It's probably what I was thinking about, or I'm drawn to these types of songs at this particular point in time. And on this record, I realized after I'd put everything together that this was sort of an Art Rosenbaum record.

Art died in the fall of 2022, and he was just such a big influence on me growing up. Not only as a documentarian and an artist, but a musician. I learned so many songs from him, and since I was a little kid, he was always really encouraging of me and my interest in traditional music. He was always pointing things out or suggesting things. The first time I ever heard about the Anthology Of American Folk Music, that Harry Smith Anthology, was from him, before it was reissued. He knew it was gonna happen, because they consulted him about it, I guess. He said, "When this comes out, you definitely need to grab a copy, because this was this thing we all listened to in the folk revival in the '50s when it came out." He turned me onto all kinds of stuff, so I was always really grateful to him. He kept that up through the years, especially as I started playing out in my 20s. When I'd play in Atlanta or Athens sometimes, he'd sit in and join me in my set, which was always really nice. That song was one that was always around. It's a simple tune, in a way, but it has interesting lines. I started kicking it around and played that one.

You said you discovered the unintentional theme. The other theme is "leaving," "going," "gone." These sort of traveling words come up again and again on this record. Was that also something you didn't realize was happening?

FUSSELL: Yeah, totally. I didn't know. I was like, "Why do all these songs have something to do with going somewhere or leaving town?" And it's probably because I've been traveling so much lately in the past three, four years, just playing so much music. But also, I don't know, just maybe getting older, and hearing the record that way, too. Traveling through life.

It's also one of the main themes of folksongs, generally speaking. Goin' somewhere.

FUSSELL: [laughs] It's true. On the previous records, there's probably a fair amount of that, too. This one, definitely. I got a little self-conscious about the number of songs that had the word "going" in it.

4. "Feeing Day"

You brought up the horns earlier. That's what stood out on this one to me. It reminded me of "Washington," off your last record, the way that French horn comes through at the end.

FUSSELL: Oh, yeah.

For the instruments you don't play, like the horns, do you take on a kind of bandleader role? Are you writing parts for your collaborators, or do you give them leeway to play around with it?

FUSSELL: Some of these parts were written by Jim Elkington, and some were written by me, and some are a combination of both. For a lot of the instruments, I give people free rein to feel it out, with some suggestion as to what sort of style I'm looking for. But with a lot of the strings and horns, Jim pretty much did all the string arrangements on this record. And with the horns, I kind of had melodic lines that I thought would be nice, and I had Jim write those out. But like, on the previous song we were just talking about, that break that's in there on "Leaving Here" is a saxophone and a harmonica playing together in unison. I wanted that to happen at one point on this record, because I'd heard it on a few recordings of Peruvian huayno music that I really liked, where there was multiple woodwind and reeded instruments together that were very different timbres. So something really round and soft, like a saxophone, playing against something that's really reedy and edgy, like a harmonica, has a really interesting effect.

But on this one, this is another Art Rosenbaum joint. [laughs] I knew that he had traveled a good bit in the UK in the '60s and '70s, but he told me that he and his wife Margo were in Scotland in the early '70s, and they had borrowed a tape recorded from somebody and decided to go on a field trip up north to Aberdeenshire. I think they located Jeannie Robertson, the great ballad singer, and then she might have led them to some other people. But they located this family, the McPhee family, and they recorded some ballads.

I'm not really in the business of doing Irish and Scottish folksongs, just because there's so many people who are great that. But Art had given me a CD-R of those recordings. They've never been released, but you can find them in his collection at [the University of Georgia], where all his stuff is housed. He had given me this CD with a bunch of that stuff on it, and this one song, I was just like, "I've got to work up a version of this." The melody was so beautiful. And actually, I would play it every four or five shows for a while. I played it live for a couple years before I ever recorded it. So then when it came time to record it, I wanted to have it be pretty simple, but maybe have some element in there that I wouldn't do [live]. Not just acoustic guitar and vocal. So the horn thing, the melody kind of allows for that, but I didn't want it to take over for the song. I hope it worked out.

5. "When I'm Called"

The first thing I thought when I heard this song – without context, I didn't know where it came from – was a Simpsons chalkboard gag. When Bart's writing what he's not supposed to do anymore.

FUSSELL: [laughs] Right, punitive writing.

It's got to be the first mention of breakdancing in one of your songs, too, I imagine.

FUSSELL: [laughs] Yeah. I have this friend, Chris Sullivan, who's an artist. He lives in New Orleans, but I first met him in California. He lived in San Francisco for a long time, and he's a photographer and a poet. He's also, for years, collected little pieces of writing, just whatever he could find. Found poetry and things like that. He used to publish them. He had this little zine called The Journal Of The Public Domain that was really great, that only had three or maybe four issues. This was before Found Magazine was a thing. Anyway, Chris, I think he had actually seen this piece of writing in another show. A gallery exhibit or something of somebody else's collection. But he'd committed it to memory, this couplet, and would recite it sometimes. [laughs] I think it was originally, "I will come when I am called/ I will not breakdance in the hall/ I will not laugh when the teacher calls my name." I kind of screwed up the lyrics a little bit.

It's funny, man, because I was working up this arrangement of this other song, "Look Up Look Down That Lonesome Road." I'd known that song for a long time, and it just wasn't landing right. I don't know what it was. I had that little riff, and I was using that lyric as a space-filler, that "breakdance in the hall" thing. And then I played it live a bunch of times, and just kept that part. And it became more interesting the more I played it, and then I thought, that was the song.

That's wild. I was fairly certain the second verse was not from the same source as the first verse, because there's a dissonance there. But even though it's dissonant, it works together.

FUSSELL: Yeah, and there were a few other things that I tried in there, that were from that other song, "Look Up Look Down That Lonesome Road." Something rhythmically about them didn't work. I just sort of stripped it back, and something seemed to work this way. Sometimes a lighter touch is better.

6. "One Morning In May"

James Taylor sang this one. A lot of people have probably heard that version.

FUSSELL: Really?!

Yeah, it's on One Man Dog.

FUSSELL: Damn, I gotta look that up!

bI think that your lyrics are a little bit different, so he might have been pulling from a different source.

FUSSELL: This is another one from Art. This is one of those that is pretty widely known in the folk music canon. It's not an obscure song at all, really. But there's so many different melodies for it, and it's a narrative that falls under a bunch of different titles. It's a British folksong. It goes back a long ways, I'm pretty sure. Art had this field recording from Indiana. Shorty and Juanita Sheehan from Bean Blossom, Indiana, which is where Bill Monroe had his farm. There was a Bean Blossom Festival for many years. They were part of this Indiana bluegrass scene. But their recording of it is just gorgeous. I'd been playing this for a number of years off and on, just kicking it around, and then I tried it with a 12-string guitar and thought it sounded kind of nice.

I think I'm partial to waltzes anyway. I like waltz time. In fact, I'm a little self-conscious about it now, because "Cuckoo!" is also waltz time. I think "Feeing Day" is, too. I kind of get sucked into those easily, and then when I make a record I have to be a little bit careful about it.

So it's not 12 waltzes.

FUSSELL: Yeah, exactly.

There's a couple lines in here I wanted to ask you about. One is "Never place your affections on a green growing tree." That pops up again on "Going To Georgia." I think it draws from "On Top Of Old Smokey," that song. It's just one of those lines that pops up everywhere. Is that kind of exciting for you as a folk guy, when you can trace some lyric to multiple origin points?

FUSSELL: Yeah. There's that one. There's a few different versions of that. I've heard different types of tree.

"Green willow tree," I think, is in some of them.

FUSSELL: "Green willow tree," yeah. There's a few different ones. I think Shorty and Juanita Sheehan change theirs to "Never place your affection on a soldier so free," or something like that. But yeah, I do like that. I like phrases that come up in different songs, and you think about how they might overlap. That might have been something that in the past I wanted to avoid, just to not have those things overlap on one record. But on this record, I don't know what it was, I thought it might be kind of interesting to have the same line occur in different songs.

It's fun when you notice it, as a listening experience. It ties the whole thing together. It's almost a cliché about folk music, but understanding that these things come from a tradition, it helps hammer that home a little bit.

FUSSELL: Yeah. I'm glad you feel that way. I thought it might be interesting to have it pop back up. I do like that.

The other line I wanted to ask about was about having "a wife in Columbus." I imagined that might have resonated with you, being from Columbus, Georgia. Do you think they were talking about Columbus, Indiana? Now that I know they're from Indiana…

FUSSELL: You know, I'm not even sure. I assume they're not talking about Columbus, Georgia. There was also a popular fiddle tune called "Road To Columbus." And people from around where I'm from, when I was a kid, old-time fiddlers would talk about it as if it was about Columbus, Georgia. But I'm not sure it was, because it was a Midwestern fiddle tune. I always assumed they were talking about Columbus, Ohio, actually. It's hard to know. But yes, I was drawn to it for that reason. [laughs]

7. "Gone To Hilo"

This is another one where I think I saw you talking about the unknowability of the places mentioned in songs. What is "Hilo"? What is "Rio"?

FUSSELL: Let's see, where did I learn this from? I think I learned it from a Paul Clayton record. Paul Clayton was a great folksong interpreter and folksinger in the '50s and '60s. A really influential person who doesn't get his due. I know that he was really influential to young Bob Dylan, when Dylan was first starting out in New York. But Paul Clayton grew up in New Bedford, Massachusetts and learned sea shanties as a kid, and maritime songs, and then collected them and did a couple records of wailing songs and things like that. Paul Clayton also made field recordings. I think he made the first recordings of Etta Baker, and he was a folklore student at [the University of Virginia]. His teacher was this guy, Arthur Kyle Davis, who made a bunch of recordings back in the '30s. He's a really interesting figure who, unfortunately, killed himself in the late '60s. I really like some of his recordings, and then, I think the Clancy Brothers had done a version [of "Gone To Hilo"]. But then there's older field recordings of that, in a more of a sea shanty performance rather than a coffeehouse folksinger/troubadour version of it.

I've always thought it was a really interesting song, and there's always, anytime you try to research this stuff, immediate controversy about where the place is. Is Hilo a mispronunciation of Hawaii? Or are they talking about somewhere else? There's an Ilo, a city in coastal Peru that was a stop-off for some of the clipper ships where these songs were initially sung. So there's some discrepancy about all that. It's hard to track down. But there's something really beautiful about that song, I think.

Are you aware of the TikTok sea shanty phenomenon at all?

FUSSELL: Somebody recently made me aware of this. I've not looked into it at all, but I remember during COVID, there was quite a bit. Did it start then?

The videos that started going viral did so in like 2021. It's all young kids, Gen Z, getting into sea shanties for whatever reason. And then what was interesting to me is that now there's just enough real-world crossover that they're having live performances of sea shanties, and the crowds are largely Gen Z.

FUSSELL: God, what a world. Sea shanties are so interesting. There's so many of those songs, but there's kind of a core group of hits, that experienced a revival during the folk revival and in songbooks in the first half of the 20th century. So yeah, I could see that being a real thing that you could get into, because it's kind of its own world. A lot of those songs have this imagery that's really romantic, and you can think about that era, and the function that those songs served aboard those ships. It's such its own world.

8. "Who Killed Poor Robin?"

I heard the recording that Art Rosenbaum took of this in the Ozarks, but it's a British tune. Is that typical of how these songs travel? Have you encountered a lot of songs that are British in origin, but then you end up hearing a version that's from the South or from Appalachia?

FUSSELL: Oh, yeah. So many of them are like that. That one goes back a long way. That's an old tune, but I think it was published early on as a broadside. That's another funny thing about all these folk ballads and things. It's hard to pin down authorship, but there's sort of an assumption that they existed as part of oral tradition for hundreds of years, when actually, they were being printed up and sold pretty early on. I mean, yes, there was oral dissemination of folksongs, [but that's] in addition to being a part of print-based culture, too. It happened in parallel for a long time.

It's also funny, going back to the sea shanty thing, sea shanties did function as sea shanties. Literally accompanying the work that these guys were doing on these clipper ships. But they're also being traded back and forth along ports, but then picked up by people who were singers, who were stationary, and maybe some of those people were urban folks, and putting that into whatever folk revival is going on. Some of the sea shanties would become crystallized versions, from people like A.L. Lloyd or, later, Paul Clayton or Joan Baez. A sea shanty might have a longer life as a coffeehouse folksong than it ever did in its original context. That's kind of fun to think about. What were we talking about? [laughs]

"Who Killed Poor Robin?"

FUSSELL: Oh, right.

But that's a point well-made, in talking about how these songs travel. The lyric itself, I think is kind of hilarious. It's sort of weird and dark, but I know it must have been written for children. I'm picturing kindergartners singing about this very elaborate funeral.

FUSSELL: Oh, yeah, a lot of those songs are kind of violent, too. Or cutthroat, at least. Harsh. Another one of those is "Froggy Went a-Courtin'." That's a really old text. I think that goes back to the 1100s. A lot of songs from that era are about animals doing something kind of ritualistic.

I know this metal band, Green Lung, who have a version of "One For Sorrow," if you know that song about magpies.

FUSSELL: Yeah, yeah.

They do kind of have this edge to them that lends itself to that kind of interpretation. I think this song, too, is really playful, though. It's not just morbid. It's kind of fun.

FUSSELL: No, yeah. There's some humor in there. I like that one. I think some of the emphasis has changed over the years. I'd never heard another version that's talking about the owl: "Who'll preach the funeral?/ "Me," said the Owl/ And I'll scream and I'll howl." I really like that line. There's different ones that I didn't even put in there, because I was just afraid of it getting too long and becoming rote. But there's some really good ones.

9. "Going To Georgia"

I think the sequencing worked really well for you here, because this feels like a culmination of sorts. I like that it appears at the end of the record. Did it strike you, when you decided to do this version, as a good closer?

FUSSELL: I didn't set out to do that, and then, when we built it all together, there was an openness to it. I was going back and forth about whether it should be the first song on the record or the last song on the record. And I'm glad it was the last, because I think it lends itself to that. The way it kind of builds, too, is nice. That's another one that I learned from Art Rosenbaum, and it has ties to a bunch of other songs. That song is part of a bigger family of songs, including "Cuckoo!", although, not the "Cuckoo!" I'm singing on this record. It's related to another one of those cuckoo ballads. I think it works well as a closer.

I think part of that is the last verse ending with, "I'm going to Georgia/ For to make it my home." Your autobiography maybe creeps in a little bit here. Because you live in North Carolina now, right? Is there a nostalgia for Georgia in this song?

FUSSELL: Oh, yeah. So much about where I come from musically, and when I think about my musical past and how I got into all this music, has to do with my growing up in Georgia. I think that was definitely coming through the meaning for me in this song, for sure.

When I'm Called is out now via Fat Possum.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!