We’ve Got A File On You features interviews in which artists share the stories behind the extracurricular activities that dot their careers: acting gigs, guest appearances, random internet ephemera, etc.

Every time Lupe Fiasco pauses during a thought, an interesting tension hangs in the air. It’s not that he’s searching for the right word — he’s made a career out of how easily they come to him. I imagine he’s pulling ideas apart like gossamer, gingerly separating one thought from another and setting them aside until the right moment. He speaks in dense paragraphs, organizing his thoughts with a bricklayer’s meticulous patience. He never trails off; every silence is well-considered. It’s easy to imagine stacks of notebooks filling his home, pages covered with neatly written rhymes in clear, precise script.

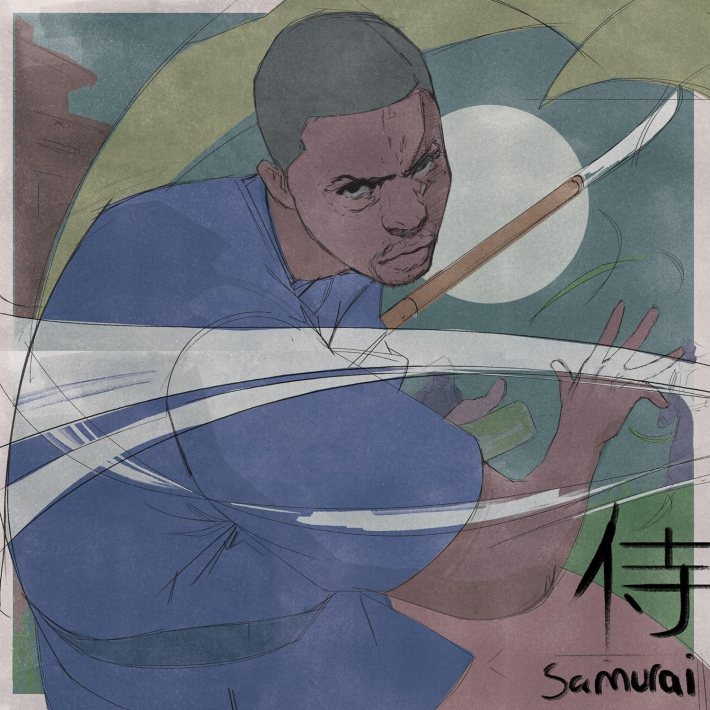

You’ll certainly find that attention to detail on Samurai, the Chicago rapper's excellent new album. Every line in each of Samurai’s eight tracks is a tightly-coiled spiral, Lupe carefully unwinding them to keep the complex rhyme schemes intact. It sounds almost meditative. Lupe’s kept up that level of care for over two decades, creating a widely diverse, far-reaching discography of incisive conceptual albums. He’s seemingly done it all, going from hyped new star to critical pariah to underground legend to his new cruising altitude of a true rapper’s rapper. His career is fascinating, its density hiding gem after gem for listeners to discover.

We connected over Zoom a couple of weeks after the release of Samurai and talked about the new record, the course he teaches at MIT, being named a Saybrook Fellow at Yale, climbing Mount Kilimanjaro, his relationships with Aesop Rock and Kanye West, and more.

Samurai (2024)

Samurai is a complicated concept album inspired by battle rap as an art form, your martial arts practice, and Amy Winehouse's voicemail for Salaam Remi, in which she talks about writing battle raps. I'm curious how you threaded the needle with those seemingly disparate ideas.

LUPE FIASCO: Well, one, it doesn't have too much to do with my martial arts. The "samurai" part is purely from that quote of her saying she's a samurai, and the references that she made, but it wasn't an album about my martial arts career. I do have unreleased songs like that, where I'm talking about karate and all these other things, but Samurai wasn't intended to be that album — it's not like you're listening to the soundtrack for a kung fu movie. But with that said, there are also reference points like "No. 1 Headband," which is referencing the Afro Samurai anime. You won't listen to this album and learn how to be a swordsman or swordswoman. I will caveat that just a little bit so people who haven't heard the album aren't like, "I'm not listening to some kung fu music."

In terms of the battle rap part and the Amy Winehouse piece, the reference points are her just saying she wants to be a samurai. But beyond that, this album's not meant to be an autobiography about her. It's not meant to be rewriting her legacy or anything like that. It is somewhat non-linear — part of that is because it's not finished and will never be finished. It is one of those projects where management, my partner Chill, was like, "We're done. This is enough. We'll sacrifice having a complete, linear narrative for the sake of having a tight, strong album." You don't need the extra three songs where she loses her powers or the battle between her and the other opponent.

So, you take all those things into context and it kind of weaves itself. There are some creative things that start with the song "Samurai" as a portrait of Amy Whitehouse in this imagined world, or leading to this imagined space. And then literally referencing her quote as the chorus. Then it's “What if?" How did she get her powers? What if she went to a battle? How would she respond if she won the battle? From that, you get those other records like "Cake "and "Outside" which are a little bit closer to the linear narrative. You ask a question that you answer with a song. So, it's not crazy heavy lifts, it's kind of moving around big pieces.

What was it that drew you to Amy Winehouse in the first place?

LUPE FIASCO: I'm a big documentary guy. Of course, we've all heard her music and are aware of her journey through the musical space, but I think there's something about those documentaries that go in-depth with an artist where you get to see the creative process and stuff like that. For me, watching that documentary, [Amy] — it was literally just that quote that inspired everything. If that quote wasn't in the documentary, you wouldn't get Samurai. You wouldn't have an album about Amy Winehouse as a battle rapper. You probably would get some interesting reference points scattered across some other songs, somewhere in another Lupe universe, but you wouldn't have got this concentrated portrait of her.

I'm impressed by her as a craftswoman, as a jazz singer, writer, a producer — all these different aspects of her as an artist. She's an amazing songwriter and performer — which we know outside of the documentary. But then watching the documentary and weaving all those things together, it's like, "This was a pretty fascinating person who, unfortunately, we lost too soon." A lot of my work is breathing life into things that have passed. You see it in records like The Cool. Songs like "Jonylah Forever" and "Alan Forever," where I try to take something that has passed on and bring it back into this world in an interesting and dignified kind of way.

When you're trying to breathe life into things that have passed, and perhaps specifically for the songs that are conjecture about Amy Winehouse, what kind of writing exercises do you do to inhabit them?

LUPE FIASCO: To be honest, I really don't. A lot of my work as a student in rap was decades ago. A lot of the things that I do, how I write, my workflow, my process, all that stuff, is what I practiced when I was younger.Learning how to rap, learning how to write songs, learning how to make albums — all that stuff is old. What you're getting now is me just executing on those techniques. It's not like I have to go back and re-study a writing style to get in this space.

I've studied so many different writing styles and stylistic approaches to rap, and being able to read a beat — from my perspective specifically, I don't think there's a standardized way to do it. If everybody approaches the same beat, there's a possibility that you'll find similar patterns. People are gonna pick up on similar things. But with that said, I can read a beat and understand what needs to be there from a flow and a tonal standpoint, and then the words are the words. It's not like I had to go into the "Samurai Boot Camp" to write this record. It was more just taking those standard models.

At one point I wanted this record to have a female voice throughout. I was going to write the record and just have somebody else perform it. So it's decisions like that, thinking through them somewhat seriously, like, "That would be interesting as a project." That will require another level and I would get a voice actress or somebody in that space and say, "Here's a project. I need you to rap it," and then go through whatever that takes to get them to get to the point where they can pull off some of the pieces. Kind of like a musical, you know?

Given your love for documentaries, I'm curious if Samurai ended up being a way to write your own documentary about your work and process.

LUPE FIASCO: Not necessarily. To land on the technical part just a little bit more — in the class I teach at MIT, we're developing this unit about rap portraiture, kind of standardizing what it means to create a portrait. Throughout my career, there have been examples of me doing portraiture, some public, some private. One of the public pieces is called "Big Energy" — no shade to Latto. I got commissioned for a documentary about Dick Gregory, and it was like, "Can you make a record documentary?" So, I decided I'm gonna make a portrait of Dick Gregory.

My class at MIT is run kind of like a fine arts class, so the idea is, what does that standardized form look like? What are the rules of portraiture? What are some prototypical examples? You have Nas's "U.B.R. (Unauthorized Biography Of Rakim)" and others that stand as portraiture. But what happens when you standardize it in a certain way? What elements do you need to have? What's the structure of the record? How do you gather the data for it? So we have a standardized session of what it means to create portraiture. You do exercises, and there's an exam on it. It’s pretty formal in that sense.

So, you can kind of look at the Samurai project as kind of a prototypical approach to portraiture that we've now standardized in the past couple of years. Remember, this record is about four years old. We started it kind of at the beginning of the pandemic as just a single portrait, which was the song "Samurai." It extended into a full project — which got set aside to do Drill Music In Zion, which came out before Samurai. Samurai was sitting in various states of completion for several years. A lot of the things that are in it are not real-time to me. I'm looking at that piece and pulling elements from it, stripping out other things, and then putting it in a format that I can teach in my course.

Teaching At MIT

What is the structure of that course? Where does it start and where do your students end up?

LUPE FIASCO: It's called "Rap Theory & Practice." I've taught it for two years, but I'm in negotiation to teach it for an extended period of time. We do a lot of rap history, structure, formal kind of things. We develop people's freestyle muscles, their improvisational skills, and all the different spectrums of writing exercises. It's framed as though you went into a very formal painting class, that's why portraiture is one unit within it. There's a "landscaping" piece that's about how we paint scenes and things like that.

It's split into two units: There's a theory class and there's a practice class. The first theory class is really big and open. There's not a lot of pressure — everybody writes, everybody records, everybody performs, so that's the standard throughout the whole thing, but in terms of expectations, it's a little bit less on the theory side. The practice course is much smaller, meaning there are fewer students, and it's way more intense. In that one, we're writing complete, full songs. Everything has to have a complete breakdown. There's an essay for every single work and a writing exercise attached to every single recorded rap. It's very, very intense and very dense because it's MIT. If it was at another school, it'd be something different.

But with that said, that course comes out of the institute that I founded with a few other emcees called the Society of Spoken Art. The course at MIT is a truncated, constrained version of the course that you would get if you were to become an apprentice at SOSA. That apprentice course is actually 52 weeks, give or take a couple here and there, but it's extremely long and extremely dense. It’s a lot of rigorous exercises for rappers who are already really good at rapping. Whereas at MIT, it's a much shorter course. Some people are really good, some people not so much. Some people are still learning the ropes. But it's stuff that we've been teaching at SOSA for years that's been tailored to fit the MIT aesthetic and expectations.

What are some of the required texts or required listening for the course?

LUPE FIASCO: The listenings are vast. You listen to rap from 1979 all the way through to now. It depends on what the unit is, so if we're doing didactic, instructional-type things, there's a whole list of instructional rap — listen to a rap and learn how to do something at the end of it. So, you listen through tons of work from rap-based corporate training manuals from Wendy's back in the 80s, all the way up to "Pumpkin Pie" by Brother Ali.

The readings used to be very dense. The standard is becoming The Speech Chain [by Peter B. Denes and Elliot N. Pinson], which is this one-stop shop for everything from your lungs to your cognitive ability to process language, all the way to tech and machine learning. Everybody builds machine models, and there are voice models that they have to create. There's AI in the course. It runs the whole gamut of anything you do with your voice. How does your voice generate? How do we process language from a neuroscience standpoint? There are things about conceptual metaphor, George Lakoff — there's a myriad of reading. But, you know, I try to keep the class somewhat loose, but it's a college-level MIT course. [Laughs] It's not a fifth-grader's guide to rap type thing.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!

The Saybrook Fellowship At Yale

You were chosen to be a Saybrook Fellow at Yale last year. I'm curious about your responsibilities there.

LUPE FIASCO: That one's a little bit more fluid. [Laughs] I always say that my education level is Yale, it's not MIT. I'm lost at MIT, it's just way too fucking hard. Yale's more my speed. That's no shot at Yale because it’s also super fucking hard, but Yale is more humanities-leaning than more technical-leaning, whereas MIT is totally technical-leaning with a little bit of humanities. I did all my studies — I didn't go to college — but I did all my studying on Yale's online courses. I took all them shits. So my point of view, my education level post-high school, is me just dipping and diving out of these Yale lectures. I always had an affinity and relationship with the school. One of the professors, who was actually in a cohort of mine for the first year at MIT, is a geneticist who teaches and has a lab at Yale. The head of Saybrook College, the head of house, is from Chicago and also teaches ecology at Yale.

So, it was just kind of knowing and meeting people. The Saybrook Fellowship is really an alumni thing, but they sometimes invite special guests to come in and be a part of it. It's a four-year program. There are no demands, it's just like, "Hey, here's a Yale ID, do whatever the fuck you want." [Laughs] I've spoken in a class, I got access to the college, and all this other stuff. It's a cool piece, and I'll be there for the next four years or so.

I always say that MIT is like going to work, Yale is like going to school. I never went to college, so I look at my freshman year of college being the two years that I've been at MIT. I was living in Boston, going to campus every day, just really absorbing it. Yale has a deeper, richer humanities program and collegial atmosphere. It might be like my graduate school experience. I learn more at Yale. Just being on campus is different than being on campus at MIT. They're two different schools, and they complement and compete against each other in different ways. When you step on Yale's campus and you're immediately learning things, whereas, when you step on MIT campus, you're sitting there, completely mind fucked, because calculus. if you don't know calculus, you're fucking dead.

It sounds like you’re having a lot of fun.

LUPE FIASCO: Yeah, I'm very intellectual and they're both nerdy places. I think Yale speaks to a different part of my spirit and mind, whereas MIT is a very challenging place. Our motto at MIT is "I hate this fucking place, IHTFP." [Laughs] It's just notoriously difficult and challenging, but I look at that as a good thing. I apply that to my students, like, "Hey, this shit's meant to be hard because you're fucking hard, so let's fucking kill it." I love it — I have a hat that says YIT, the logo from Yale, and then the "IT" from MIT. They both hate it when I wear it. [Laughs] It's the best of both worlds.

Climbing Mount Kilimanjaro (2010)

How did you get involved in the 2010 Mount Kilimanjaro climb? Jessica Biel, Emile Hirsch, Santigold, and a few others were also involved in it. How did that come about?

LUPE FIASCO: Jimmy Chin, [who directed] Free Solo, was our climbing coordinator for that. That shit was crazy. It was an all-star team of folks. It was put on by my man Kenna, who's an amazing singer. He comes from that Star Trak, Pharrell, Neptunes, Virginia world. He set it up. The thing was, he had tried to climb it before by himself, couldn't do it, and was really bummed about it. So, he's going back to do it again with a bunch of sponsors, and this time, he's bringing all his friends type shit. It was dope.

Pieces and parts connected to it had this water purification tablet that we were hocking on behalf of Proctor & Gamble. And Kenna's really good friends with Justin Timberlake and all these different folks, so there's a star-studded cast. Me and Kenna are really cool, so they reached out to me. The rest is history. Go to Africa — first time there — climb the [continent’s] highest peak, get to the top, cry like a baby, and then can't wait to get back to LA. [Laughs] Like, "Get me the fuck outta here." But it's a real mountain. It's one of the Seven Summits. It's one of the easier summits, but it's also not easy. Like, it's fucking 19,000 feet. It's a bitch to climb.

Have you done any similar hikes since, or is that even still a part of your life at this point?

LUPE FIASCO: Yeah, I do some hiking around the mountains in California. I'll probably do this next year — I want to go to Everest Base Camp. I think it's like 16,000 feet, maybe a little more than that. I don't want to climb Everest. I did my one summit, I'm cool, but I do want to go to Base Camp.

Appearance On Empire

In season four, episode 12, you appeared for about 30 seconds and bought an apartment. What was that experience like and how did it come about?

LUPE FIASCO: I'll make it real for you. I'm literally looking at a check that I need to go and put in the bank for the grand total of — prepare yourself — $5.78. [Laughs] I get random checks from my appearance that are like, five bucks, 20 bucks. Oh, I guess somebody watched it or downloaded it somewhere. But yeah, it's a little gift.

Who reached out to who for that appearance?

LUPE FIASCO: Hmm, I don't remember. I think that was around the time when Empire was kind of on its descent from greatness. It was still kind of cool, but I think they were just getting as many celebrity cameos for low-hanging fruit. They shot it in Chicago, the episode took place in Chicago, and it was kind of like, "Alright, I'm in Chicago." So I think it was a little bit of that, just kind of some local Chicago talent situation. But then also, like, "Lupe is kind of a C-Lister. Put them in there for 30 seconds."

Collaborating With Aesop Rock (2022-Present)

There's a video that I found from 2021 on YouTube that I believe was probably a capture of an IG live. It's this talk about how and why we should appreciate Aesop Rock. In December 2022, you, Aesop, and Blockhead put out "Pumpkin Seeds." For a good portion of underground rap fans, especially those of us in our late 30s, that was exciting. Could you talk me through how that connection and collaboration came about?

LUPE FIASCO: Yeah, I have always been a huge fan of Aesop Rock. He's a member of SOSA and I teach him in my class. He actually made some beats for it. There's an MIT beat tape library that my students have access to, and so Aesop sent some beats in. But, yeah, him, Homeboy Sandman, MF DOOM, those are the guys that I listen to professionally. Like I said, my student years were when I was younger, but in my older years, if I'm trying to refine and be challenged I listen to Aesop Rock and Homeboy Sandman.

[Aesop is] the homie. We have had interesting conversations, bounced ideas off each other and stuff like that. He's the guy that I talk to. You assume that all artists have to be cool with such and such — I'm really not cool with any fucking body. I'm a cool guy, but like, I don't have Lil Baby's phone number, you know what I'm saying? [Laughs] I can't get in touch with Rakim, but I definitely got Aesop's phone number. He's gonna pick up the phone and we're gonna talk some shit. I look at him as a mentor at a distance, in terms of mentoring under his work, not under him personally, but also genuinely as a friend.

That collaboration ["Pumpkin Seeds"] actually comes from Nikki Jean in a very roundabout way. She and I are like Murtaugh and Riggs from Lethal Weapon when it comes to records. She's been on "Hip-Hop Saved My Life," and she's all over Tetsuo & Youth. Every time we work together, it's always an interesting record. She's a Minneapolis native, and actually works at Rhymesayers as well as being an artist that's signed there. She's always around those guys. [The collaboration] came through a conversation, and she was like, "Yeah, I'll hit Lu," so you get "Pumpkin Seeds" from that. And there's more coming too.

Child Rebel Soldier And Rapping On Thom Yorke Samples

You have a vast discography, and there are some notable moments where you've rapped over samples from various Thom Yorke projects. There’s the "National Anthem Freestyle" on the Enemy Of The State mixtape, "Animal Pharm," which samples "Ingenue" by Atoms For Peace, and then your group Child Rebel Soldier sampled "The Eraser" for "Us Placers." What draws you specifically to his music and makes you want to rap on it?

LUPE FIASCO: I was just in London at Heathrow, and [Colin Greenwood] the bass player from Radiohead was there, so I got his autograph. He signed a book for me. But, alright, I'm gonna give you the whole download. Me doing records over the Radiohead [samples] is [Child Rebel Soldier]. It [was originally] me, Kanye, and Pharrell. It became this group — Pharrell has beats, Ye got beats, I got beats. But then it was like, "Well, what are you gonna rap about?" I decided I was gonna rap about the downfall of being famous. The downfall of luxury, the dark side. If you listen to "Us Placers," that's what that is. I went back to P and was like, "Let's just let that be the thing. I'm not rich, but you rich than a motherfucker. Ye rich. Look, why don't it just be rich motherfuckers' first-world problems over these ethereal-ass Radiohead beats." It kept getting lost in the sauce and there was a realization that this was not gonna happen. People kept putting it on me, and it's like, "Hey, it ain't me." Pharrell is at Louis Vuitton, Ye is in some fucking factory somewhere pumping out socks. So [now], I'm like fuck it, I'm gonna reboot CRS in the next six months, maybe next year — Tyler has one of the CRS records — but it's gonna go back to the original energy, which was me rapping over Radiohead beats.

It's this weird relationship, because it's kind of like, do I put it out as freestyles because I'll never be able to clear those records? I’ve always wanted to do an album with their producer, Nigel Godrich, [so] do I go work with Nigel? I know I'm not gonna be able to work with Radiohead and do an album with them, that shit's pie in the sky. I'll just go back to that original [vibe], just go back and find those dope loops and samples from Radiohead or their solo records, loop the shit up, and make little beats out of it, and crush with some dope ass lyrics. I’ll either do some loosie freestyle shit or a proper tape, get sued for it, and keep it moving. You can take those records, the "National Anthem" record, "Us Placers," and "Animal Pharm," as the first three singles. You'll probably get another five or six. We'll see.

Relationship With Kanye West

There's a persistent rumor that you were present when Kanye was making all the beats that he'd eventually give to Jay-Z for The Blueprint. One, is that true? And two, what was your relationship like back in those early days of his career?

LUPE FIASCO: I don't think that that's true, but I can't confirm or deny it because I've been around Ye for a long time, and he's made and played beats and that were his that he gave to other people. I don't know what the energy or the intentions were. The stuff that's on The Blueprint might have been shit that he had a long time ago. I was not around him while he was making The Blueprint — that's not a thing. I was in the studio with Jay multiple times, though. I was around Jay for The Black Album. I gave him the beat for "What More Can I Say" and some other shit.

My relationship with Ye is very, um, interesting. Ye has always been a friend and a homie. I've always respected him as an artist. He's still a creative genius, a great curator of folk. I remember he would come up to my apartment in Chicago, and he would just be like, "I can't even pronounce nothing. Pass that Ver-Say-See!" If you were around back then, he was always hitting you with verses. He wanted to get your opinion on his lyrics, and that shit will pop up years later on one of his big ass hits. It'd be like, "Oh, he spit that shit to me in the kitchen."

I remember we had a production house in Chicago, and he came by because he knew some of them. All those producers from Chicago are from the No ID, Twilite Tone lineage. Ye's from that. Boogz, another producer we had named Pro, they're all from that same lineage. Even Hitmaka — we called him Iceberg back then — he's from that whole world. So, these motherfuckers would be at the house, just vibing. I remember Ye came through one time, and it was this sample that I had that I wanted Pro to make a beat out of. Pro is very slow and meticulous, whereas Ye was more industry trained, so he'd get in, get out, keep it moving. I remember Ye took the record from Pro, went in the room, chopped that shit up, made a beat out of it, and left in like 10 minutes.

But, you know, I've also had some bullshit with Ye. I'm not gonna sugarcoat anything with him. We've had our moments where I was like, "I don't fuck with this dude." But then other moments where I was like, "I really, really fuck with this dude." At this point, I really fuck with Ye. I think he's still a creative genius. I think he has things he has to settle amongst himself and his community, but in terms of my relationship with him, the things we've done — been around the world on tour and been in groups together and did all that shit, he's earned his spot.

Offering To Destroy Lasers With A Laser (2015)

In 2015 you offered to destroy copies of Lasers with an actual laser. Did anyone ever take you up on that?

LUPE FIASCO: They did not, but that would've been cool as shit. Now that I'm at MIT, I have access to all kinds of lasers, so it's still open. One of my students, his name is Alex, is a fucking amazing emcee. Very in the line of an Aesop Rock, just super technical type crazy. But he's also a nuclear physicist, that's his real job. He's a fucking proper particle physicist who shoots lasers at materials to find the Higgs-Boson type shit. Very sought after, Caltech, MIT grad student, the whole shit — super genius. He works at a lab at MIT, and he made a cover of Lasers with a laser. He gave it to me as a gift at the end of the semester. It's sitting on my desk at MIT. It's the illest shit ever.

I was gonna ask what kind of laser you had access to, and it sounds like you have access to a lot now.

LUPE FIASCO: Yeah, I have more lasers now. [Laughs] MIT's a university, but for the most part, it's a research institute, and it's very, very jank. People think it's like this super clean, super tech — some spaces of MIT are, but the majority of MIT is just learning labs. It's not enough radiation to kill you, but enough to teach you a lesson type shit. So, there are labs with proper lasers. When you see [headlines like] "MIT Professors Discover a New Particle," that shit's real! And it'll be that chunky closet right there with the laser in it, or in this fucked up-looking lab. But, yeah, you got access to the state-of-the-art, if-they-don't-have-it-they'll-build-it type shit. If you want to learn about it, find somebody who'll train you up to be in the lab, and you'll be in there fucking shooting lasers at graphite trying to knock out some particles.

His Post-Punk Band Japanese Cartoon

Is your band Japanese Cartoon still active?

LUPE FIASCO: Yep, it is! I just met with Graham Burris, who's the bass player for Japanese Cartoon. We've been itching for the past decade to just put the record out properly. It never officially came out — we kind of did it on some punk rock shit back in the day. We wanted to kind of use Atlantic to put it out, and I remember they were like, "This shit's weird." Then seven months later, they were like, "We should put that shit out!" But now, because it's ours, we own it, it was like, "Yo, let's put it out." Just the first album, In The Jaws Of The Lords Of Death, should be coming out officially by the end of the year. We're not gonna do a bunch of crazy things around it like shoot videos and shit, but you'll get a proper release. You can go on Apple Music and listen to it and order the vinyl and all that. This is the year of like I said, even with the CRS shit, it's time to go back to those old things and finish them, put them out. Let people experience it. Move on to the next.

Horror Movies And His Songs On The Fright Night And Prom Night Soundtracks

You've had songs on two different horror movie soundtracks, Fright Night and Prom Night. Are you a horror fan?

LUPE FIASCO: Not particularly. I do enjoy the macabre to a degree, but not to the point of horror. I don't believe in ghosts, none of that shit. I'm more interested in the reality or the source material of why we have certain “horror” traditions. Vampires are anti-semitic. The skull and crossbones is related toblood diseases. They thought people were coming back from the grave to suck the blood out of people, but they just had hepatitis. It's those stories that I'm more interested in, not the final product of them. I'm more curious about how we got to vampires or witches — that's some Christian persecution of people for property rights or inheritance. It's like, "John just died, and his wife is going to inherit his farmland." "Oh, really? You know, she's a witch." And then all her land is relinquished to the church. To me, that's the horror of it — humans ain't shit. If I’m watching Dracula, I'm interested in it because of some of the other layers of anthropology that exist behind it.

Samurai is out now via 1st And 15th Too/Thirty Tigers.