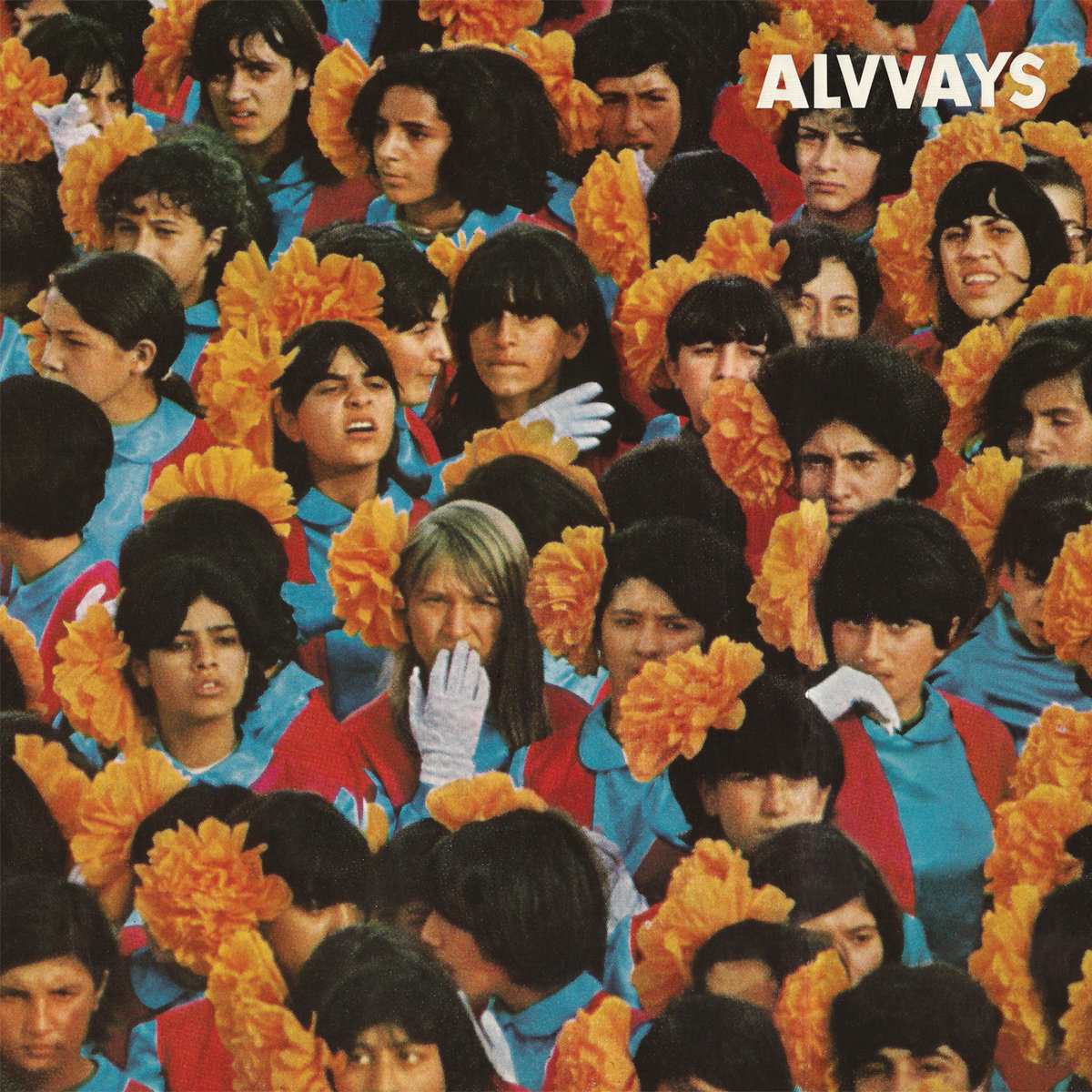

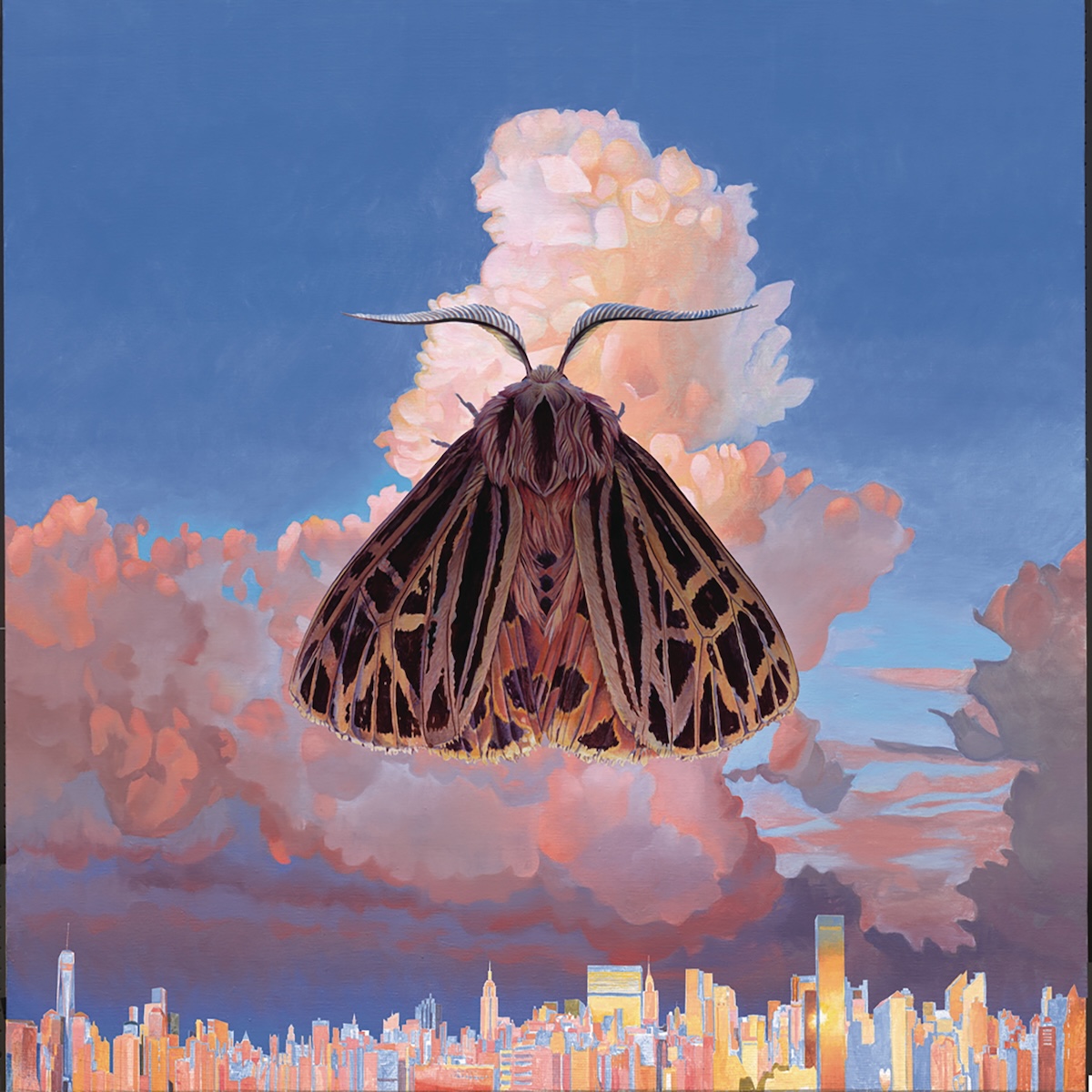

- Polyvinyl

- 2014

For a long time, Alvvays felt like one of the best-kept secrets in all of indie rock, save for perhaps their home country of Canada, which honored them twice with Juno Awards in the last decade. Then 2022's critically and fan-adored Blue Rev happened, and the Canadian dream-poppers went global.

There's no other way to describe it. The best parallel I can think of in recent history is what happened with Future Islands, a once-underground Baltimore band that caught fire in 2014 on the strength of a bewitching Letterman performance and no-skips album Singles — their fourth overall. Alvvays never ensnared the internet the way Samuel T. Herring did by clawing at the air on NBC, but their slow-burn approach to stardom (capped offwith a Best Alternative Music Performance Grammy nod this year) should be studied — especially since Alvvays never particularly appeared intent on fame at all.

Not that they aren't hard workers with a unique perspective on Happy Foot/Sad Foot (LA readers, IYKYK) ‘80s-styled ‘60s pop. But rather than lead with stage theatrics, social-media stunts, or tortured synthpop bangers, Alvvays had ocean-floor-deep earnestness, classic Smiths-inspired guitar jangle, and an unexpected vocal hero in Molly Rankin. The singer-songwriter's otherworldly and vulnerable pitch never quite manages to nail the note (as my audio engineer husband once pointed out) but still soars, fades, and blends into harmony in this perfectly imperfect way that remains eerily unmatched by her contemporaries.

Considering the height of Alvvays' current fandom, it's mind-boggling to think that: one, they've only produced three albums, and two, their self-titled debut came out 10 years ago today. I'm actually embarrassed to admit that I caught on slowly to Alvvays, but I'll never forget exactly where I was when I did hear them. It was spring 2016 and I was in Texas for SXSW. I wasn't at a show or anything — I had actually hoofed it down the road to a coffee shop for a midday cold brew. In that cafe, the employees were playing Alvvays' self-titled, which had come out almost two years prior. While waiting to be handed my order, I listened to the daydreamy strains of "Archie, Marry Me" and "Next Of Kin" while thinking, "Wait…who is this?" And so I swallowed my pride (pride's overrated) and asked the barista whom they were playing.

Fortunately for me, Alvvays were then preparing their second album, the equally delightful Antisocialites. The same year it came out, I moved to Los Angeles, started driving again for the first time since 2008, and listened to both Alvvays albums on nearly every commute to work, marveling at how I never, ever became tired of these songs. That is the magic of Alvvays. Their music is sweet, completely unassuming, warm and sincere, and sprinkled with memorable little catch phrases — Hey, hey! Marry me, Archie! — that inspire fans to scream-chant them in a concert hall.

As modest and self-effacing as the group appears from the outset, Alvvays have strong musical roots, particularly in Rankin's family. The daughter of John Morris Rankin, a fiddler with the Celtic-folk group the Rankin Family, Molly grew up in Nova Scotia and actually wrote and sang on "Sunset," on the group's 2007 effort Reunion. When she wasn't involved in the family band, Molly and her neighbor and keyboardist Kerri MacLellan would write together. Later, they connected with guitarist Alec O'Hanley, who was playing around the Prince Edward Island circuit in bands like Two Hours Traffic and assisted in helping Molly release a solo EP. By 2011, Molly, MacLellan, and O'Hanley recruited drummer Phil MacIsaac and bassist Brian Murphy to round out what would become Alvvays — spelled that way because there was already a band called "Always" signed to Sony. (Sheridan Riley has since replaced Murphy, and Alvvays now tour with rotating bassists based on availability.)

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!

A decent chunk of Alvvays was written by O'Hanley and Rankin on Prince Edward Island, in a remote farmhouse where — funny story — they nearly froze to death one night after a six-feet snowfall. (They moved out shortly after.)

Alvvays then relocated to Toronto and began their quest to properly record their debut. Alvvays was actually made all the way west in Calgary with fellow Canadians Chad VanGaalen (Women) and Graham Walsh, plus '90s hard-rock figurehead John Agnello, who helped mix. The timeline was a lot more stretched out than this essay makes it sound. The Alvvays members had day jobs to attend and little money to finance their first album without a record label's help.

"We were sitting on the egg for a while," Rankin told Drowned In Sound. "Also, we were working on becoming comfortable together on stage, so we played a lot of low-key shows and were sorting everything out before the record actually got released. There was a lot of pressure to get the record out because it's really hard to accomplish anything when you don't have a record. We just kept on annoying everyone around us and waiting and waiting and continuing to have everything the way we wanted before it got thrust onto the internet."

Shuttled along by tours with Peter Bjorn And John and the Decemberists, as well as SXSW showcases, Alvvays were eventually signed by Polyvinyl in the States and snagged a well-deserved #1 college radio hit with "Archie, Marry Me" — a yearning, festival-ready indie-pop nugget that comes off much more profound than it was intended.

As opposed to Laura Nyro's "Wedding Bell Blues," which is a genuinely heartfelt plea for matrimony, Rankin subverts her own ambivalence with a story about a woman hoping her risk-averse, in-debt beau will just "sign some papers" so the neighbors will stop talking about their "living in sin." Why? Because it's just what people do, right? "We are all in our 20s and watch a lot of people ‘grow up' and get mortgages and have big dumb weddings," Rankin told The Line Of Best Fit of "Archie" in 2014. "This song takes the piss out of that. In society it's sort of looked at as ‘The Next Level.' The song is talking about the ‘in-the-cell-beside-you' Bonnie and Clyde type of love."

One of the things I love most about Alvvays — other than their inability to write a bad song — is how their lyrics are often not even remotely about what you think they're about. It's a nostalgic reminder of a time before bedroom pop took over in the late 2010s (Soccer Mommy, Girlpool, Frankie Cosmos) and then doubled down during the 2020s pandemic era, where "sad girl" songwriters (Clairo, Olivia Rodrigo, Gracie Abrams) flourished with more straightforward verbiage.

Another chunk of Alvvays, for instance, was written in a smoothie hut where Rankin worked in Toronto. "It was the bleakest time period of the year, so maybe there was some longing for water and sunshine and summery, beachy weather. There is a melancholic theme throughout the weather, but most of it is longing for summer… or a light at the end of the tunnel," she told VICE.

Rankin's linking Alvvays’ mood to the famously unforgiving Canadian winter brings to mind other freezing, sunless regions' propensity for outstanding jangle pop — Sweden's Labrador Records being my favorite example of housing artists who are so talented at threading the happy-sad needle. Even if Alvvays' words often belie deeper meaning than just "girl aches for boy," every song on their debut radiates plaintiveness on some level. Rankin lets her featherweight vocal gradually gain power on "The Ones Who Love You," which is followed by the more percussive "Next Of Kin," where you can practically visualize the track's layers softly bleeding into one another.

Alvvays diehards like to call forth "Archie," "Adult Diversion," "Party Police," and "Atop A Cake" as real album standouts, but I've always been partial to "The Agency Group," which reels with dismissal as Rankin holds out tentative hope for connection with someone "suffering from a case of sobriety." When you whisper you don't think of me that way… When I mention you don't mean that much to me… It's an anxious spiral in the vein of "Well, I don't care if you don't." Except Rankin is not plugging a dam of feelings like Robert Smith — her protagonist is detached yet regretful. She transmits these seemingly divergent states of being with such casual grace. It's poetic and plainspoken.

Looking back, it's almost amusing to observe what reviewers made of Alvvays. Most to all were complimentary of the band's knack for ‘80s guitar jangle n' fuzz and their vintage tape-hiss aesthetic. Looking a little deeper, however, I notice some superficial reads of their lyrics as being only about quarter-life concerns, overly twee, and way too mired in themes of unrequited love and rejection. We underestimated a lot of millennial pop cultural product back then. There's a reason Lena Dunham's Girls got a second life with Gen Z; to them, the satire is completely obvious.

Happily, subsequent records Antisocialites and Blue Rev have pushed back on that silly little cardigan-sweater narrative. Not that there's anything wrong with lovey lyrics and other C86-compilation delights. It's just that Alvvays hinted at the range its creators were capable of, and history has gone on to demonstrate that and so much more.