When talking Black Flag, the music is only a portion of the appeal. While the late-'70s Los Angeles punk scene centered around Hollywood, complete with a UK-style obsession with safety pins and hard drugs, Black Flag quickly transformed what it meant to be a punk in California.

Masterminded by the band's only consistent member, guitarist Greg Ginn, Black Flag embodied a paranoid and disillusioned revulsion against the world in a way that punk's former theatrics couldn't authentically tackle. Ginn did not "look" like a punk — no mohawk or makeup. With a starchy button-up and some plain chinos, he looked more like a nerd who sold radios. In fact, he was a nerd who sold radios, with his mail-order electronics business Solid State Transmitters transforming into SST Records as a DIY operation to release his new band's records. Intense work ethic; police-on-punk violence plaguing nearly every show; member turnover the rate of a bad restaurant, with vocalists literally hopping on and offstage at any given show; and Raymond Pettibon (Ginn's brother) creating a distinct, cohesive, and sometimes jarring design language that enveloped the band in a shadow of nihilism that only bolstered the anti-social sentiment of the lyrics. These factors all play into the mystique that made Black Flag one of the most important bands of Reagan's America. Oh yeah, along with the actual music.

Black Flag, in their original decade-long run, went through various musical phases, but they were always raw, and they always sounded like they hated you. This refusal to stand musically still leads to wild variability of typically intense opinions about their discography, still inspiring near-cliched debates to this day. Many prefer their early days, when they were fronted by either Keith Morris (later of the Circle Jerks), Ron Reyes (later of Black Flag again), or Dez Cadena (later of the Misfits? What?). This early era embodies a sort of deceptive punk simplicity: songs that portray a youthful rebellion, screamed over riffs that sound a lot more stupid than they actually are. There is a degree of fun to them, while maintaining a sense of alienation misanthropy, with a thick guitar crunch and straightforward, but inventive, basslines keeping everything marching to a strict beat.

Then there are those more sympathetic to the later period of Black Flag, the Henry Rollins era. The tale is as old as time, because Rollins himself doesn't stop telling it, but Rollins found an opportunity to sing for his favorite band after hopping onstage to do vocals for compilation cut "Clocked In," since he had to clock in for his Haagen-Dazs shift the next morning in DC. The band liked him, flew him out to LA for a newly open spot in the band, and thus began an angrier, more experimental, and sometimes off-putting era of sordid storytelling and jazz-dabbling jam sessions, ramping up the honed-in fury and wrath the band was building toward. They broke up in 1986, and many years, a lawsuit, and even a Coachella performance later, Greg Ginn decided it was time for Black Flag to saddle in for a new record, this time bringing back Ron Reyes on vocals. They released the confusing What The… in 2013.

Since then, they have been touring with pro skater Mike Vallely on vocals (only after Reyes faced his second dramatic firing from the band). This era, akin to seeing your favorite, nerdy movie franchise get a shitty reboot, has been eyeroll-inducing, but that hasn't stopped the band from keeping its cult-level devotion over the last four decades. Their logo, a broken flag, has evolved to symbolize more than a set of songs, and now provokes feelings of estrangement from the norm. The discography is vast, varied, and controversial, so you are bound to scratch your eyeballs out at what I am about to let Ginn & co. get away with. This is Black Flag, ranked from worst to best.

"What The…": not just an album title, but a reasonable audible reaction to any aspect of this record. The cover has been subject to many easy jabs over the years, but it is truly confounding that a grown adult man created that, handed it off to multiple other grown adult men, and they all said, "Looks great!" If you saw it on your friend's fridge, you would assume it to be drawn by his gifted nephew, not by his 50-year-old bandmate. But even if What The… was graced by some Pettibon-painted masterpiece, the album is a phoned-in slog. These songs all sound the exact same! "Blood And Ashes" and "Now Is The Time" literally have the same intro! The songwriting sounds like royalty-free background music of an edgy '90s sitcom. A confusing blend of multiple eras of Black Flag's sound gives us a pathetic stain on a great band's legacy that looks a little bit like the Warheads candy wrapper.

The A-side is Rollins' dead-serious rambling, and the B-side is Ginn indulging his newfound love of amateur free-jazz noodling. If only they had combined the two, they might have stood a chance with this record. Rollins' spoken word is especially baffling. Is it supposed to be funny? "Salt On A Slug" would have you think so, since the audience laughs at… well, it's hard to tell actually. The inconsistency in recording quality on the A-side makes less sense the more you think about it. It should be as easy as sticking a self-important poet in the booth and letting him riff, but every track brings a different volume and even EQ on the studio's mic. The instrumentals don't go anywhere, rendering those 6-hour rehearsals even more ridiculous in concept. The most engaging of those jams, "I'm Not Sticking Any Of You Until I Can Stick All Of You," is decent, but this split-custody style release just ends up a sad product of divorce.

This EP is Greg Ginn announcing to the world that, in case you didn't get it before, he likes to smoke weed. These four tracks are long, and feel it, with Ginn mostly messing with basic scales while the rhythm section sticks to fairly basic repetition. The result is something that only the stoned guy playing it would deem groovy. It somehow still works. Even when there are no words to accompany the music, Black Flag still radiate the energy of truly isolated individuals. Play this record around any functional adult, and you, too, will become isolated, quickly.

Dez Cadena had a short but impactful tenure as vocalist in Black Flag before hopping on second guitar. The first vocalist of the band to not be kicked out over alcohol abuse, it's somewhat fitting that the most song people hear Dez sing on is a diss track about his predecessor's predilection for buying beer in bulk. A heavy smoker, Dez's strained vocals made him sound even tougher than he was probably going for, marking a meaningless distinction for the band: the jump from "punk" to the newly-burgeoning "hardcore." Chuck Dukowski's title track bassline was so unique amongst its contemporaries that it's not hard to figure why it remains one of the most iconic intros in the punk canon. The intro riff to "American Waste" is equally menacing, but this EP is a bit more underwhelming than what came later, leaving Dez's discography as vocalist as an unfortunate victim to bad timing.

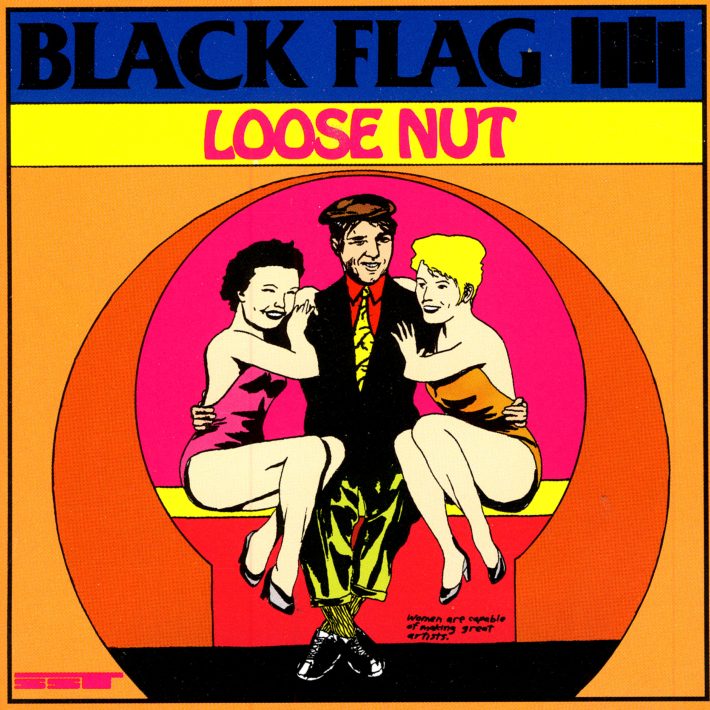

Loose Nut marks a starting point in Black Flag's history, where you, the listener, can decide to resent Greg Ginn for being a genius who hates the world and knows how to punish it, or revel in the full-blown sardonic sleaze of his singular vision. The songs are somewhat dragged out, the solo on "This Is Good" sounds like some sort of joke, but the riffs are still here. "I'm The One" is a clear highlight, along with "Modern Man," a song first recorded as a demo back in 1982. The mid-'80s were a time when hardcore bands were experimenting. Some went metal; some went melodic; some even went prog. Black Flag seem to have taken all of that as a challenge, using punk rock as their own silly putty, stretching and contorting it into a shape only they could make out. Admittedly, the production (especially the drums) works to this album’s detriment, and these songs are best heard in their live iterations.

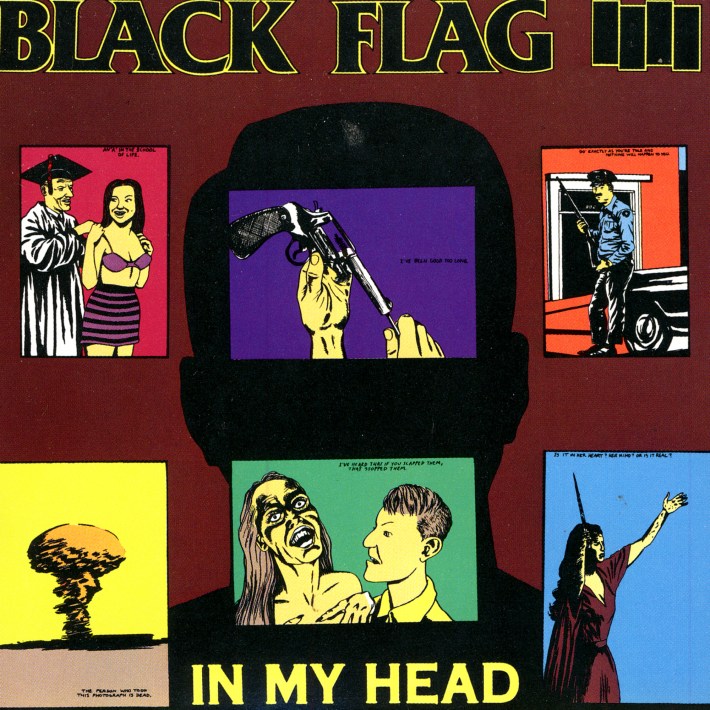

Their final LP. By this point in time every member of Black Flag had hair down their backs, and the music sounded like it… so not punk! The anger and anxiety that Black Flag encapsulated that their first, diehard fans clung to in cultish fashion? It was all still there, just weirder; the melodic break in "Retired At 21" is something they could have only pulled off a decade into being a band. "I wanna be the bullet that goes ripping through your skull," yells Rollins on the album's title track, summing up the band's interpersonal ethos in a fittingly graphic manner. The jump from Loose Nut to In My Head is probably the smallest musical development in Black Flag's career, with similar stylistic flourishes running across both albums. In My Head just enhanced it all. Repetitive dirges and dark storytelling were par for the course at this time, but Ginn and the gang had mastered their chemistry at this point. Whether the potions concocted with that chemistry were as satisfying as earlier experiments, that's up for debate, but at least the band went out with something interesting, daring, and sonically anti-social.

If Black Flag only ever released this EP, their first, they would be just as legendary as they stand today, just for the guitar tone alone. Even if it were your first time hearing the opening riff of "Nervous Breakdown," even if you were from a distant planet and had never heard a guitar in your life, that chunky distortion is telling you that this band is mean. First vocalist Keith Morris' sassy slacker delivery makes this band sound like exactly where they are from, a Southern California beach town, but it doesn't quite live up to the veins-in-the-forehead level of anger needed to carry this band into the stratosphere. Check photos of Black Flag in their early days and you see a young Keith gripping a mic in one hand and a Budweiser in the other, like they were perpetually playing a frat party. Maybe hindsight is 20/20, but it makes a lot more sense for a wannabe-poet/weightlifter who beats up fans to be doing vocals for a project like this.

Ron Reyes' vocals were a massive leap in the journey to put a voice to Black Flag's "fuck you" philosophy. Retaining the snot-nosed rebellion of Keith Morris, and tripling the decibel count, the result was a band that sounded as confrontational as their growing reputation made them out to be. Reyes (mockingly known as Chavo Pederast after his ouster) delivers his lyrics so convincingly that you would think he's saying it all for the first time out of genuine anger, which makes sense because he lived in a closet and only ate potatoes to survive. That's bound to piss a man off. This might be Black Flag at their catchiest, and some of these riffs are pretty complex despite being the foundation of a subgenre known for its rudimentary songwriting. Still, it doesn't quite capture the honed-in depiction of neurosis perfected on later releases.

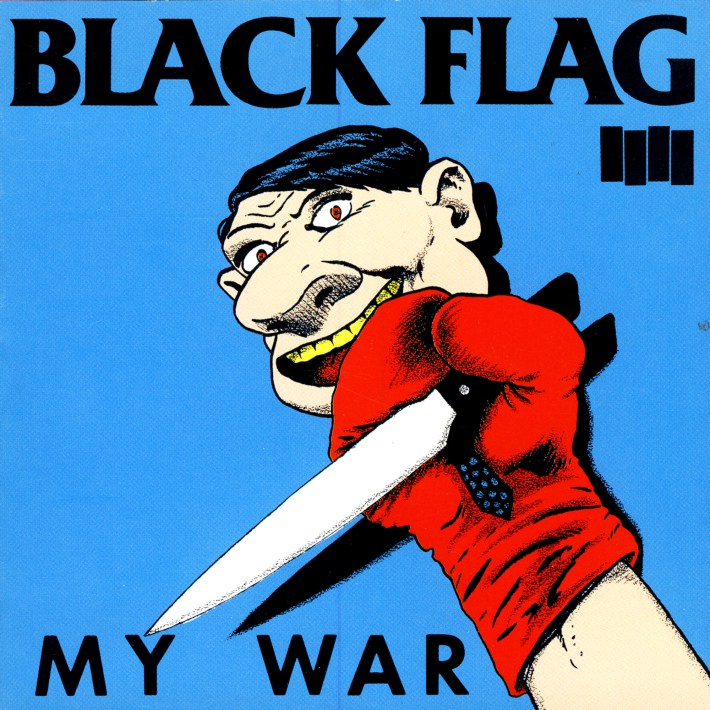

Seeing if someone likes My War is like a litmus test for the self-loathing. There isn't much of a reason to listen to this album if you don't see life as a worthless chore. I mean that as a massive compliment. Make it past the pillow-soft production and comparatively low energy for a Black Flag album (even with Bill Stevenson crushing it on drums harder than he ever could in Descendents), My War is an album that perfectly sums up depression's tight grip on your self-esteem and sense of motivation, with tracks about indecision ("Can't Decide"), feeling empty ("Nothing Left Inside"), beating your own head against a wall ("Beat My Head Against A Wall"), all of them masterclasses of lyrical angst (and subtlety). Side B of this record had a very notable and recorded impact on the grunge movement of the next decade, teaching young punks that hardcore can be slow. Almost too slow. Even approaching almost annoyingly low speeds, the frustrated screams of Rollins across all three tracks on the B-side are a feat to behold.

Riff after riff after riff after "Uh, what the hell did he just say?" Slip It In has Black Flag's metallic edge cutting sharper than ever. The heavy drudge of My War gets a healthy dose of urgency with some better production and the addition of a better bass player, Kira Roessler, beefing up the band's sound. They've even got a jazz cut, with "Obliteration" serving as your occasional reminder of the band's true love of making music to confuse young punks who first fell in love with Nervous Breakdown. The songs are long, one of punk's cardinal sins, but the riffs are repentance. They are calculated and meticulous, especially driving on "The Bars" and "Black Coffee," a song containing some of hardcore's most unexpected imagery. Anxiety encapsulated in a simple lyric: "Drinking black coffee/ Staring at the walls." No cream, no sugar, just misery. Stark imagery is all over this release: "I see the world through rat's eyes," "I've got my hands wrapped around the bars," "You see me with that black dog, that's when you walk into my ghetto." Rollins isn't telling you how he feels, he's telling you who he is. It's hard to avoid the lyrical content of the album's title track, which isn't just eyebrow-raising now, but definitely was for at least half the population the year it came out. Beyond the eye-rolling juvenility of that opener — or maybe, unfortunately, including it — Slip It In is a hellish soundtrack, an aural painting of the apocalypse that was mid-'80s Los Angeles.

If you have even the slightest clue who Black Flag are, you probably could have seen this coming like a mirror sees Henry's fist practicing for photoshoot day. It should not be a shock to anyone that this record lands atop yet another list; this is Black Flag pushed to their ideal form, just teetering on the edge of their bungee jump into full-on experimentation. It’s their first record with DC transplant Henry Rollins on vocals, whose delivery encapsulated the focused, singular anger that the band's music and lyrics had been building to over the last five years before his arrival. The double-guitar attack of Ginn and Cadena (in his only guitar credit with the band) sounds like a set of power tools malfunctioning, setting a tone of unease. "Rise Above" is the obvious classic, cementing itself as a hit with its gang-chanted chorus, essentially telling the enemy (whoever that might be) to fuck off. The band revels in their mockery of the drunken with the Cadena-penned "Thirsty And Miserable" and the re-recorded "Six Pack." "No More" and "Life Of Pain" introduce tension and build suspense like a horror movie, before they explode into a soundtrack for going postal. Images of psych wards are brought to songs like "Room 13" and "Padded Cell," with Rollins' maniacal barking on album closer "Damaged I" sounding like an unwanted dog at the shelter. This was Black Flag wrapped up in a bow, as well as a straight-jacket. Their disgust at the world, and themselves, was on balanced display, with a perfectly tense score to push it over the edge. Unfortunately, "TV Party" sticks out right smack in the middle of the album, disrupting a sequence of fury with silly, easy commentary on couch potatoes. Greg Ginn once said that after Henry Rollins joined the band, Black Flag ceased to have a sense of humor. If "TV Party" is the type of stuff Ginn finds funny, we owe Rollins a thank you. Even with that glaring flaw smacking the listener in the face, Damaged managed to encapsulate sunfried anguish and alienation in a way nobody had until then, or since.