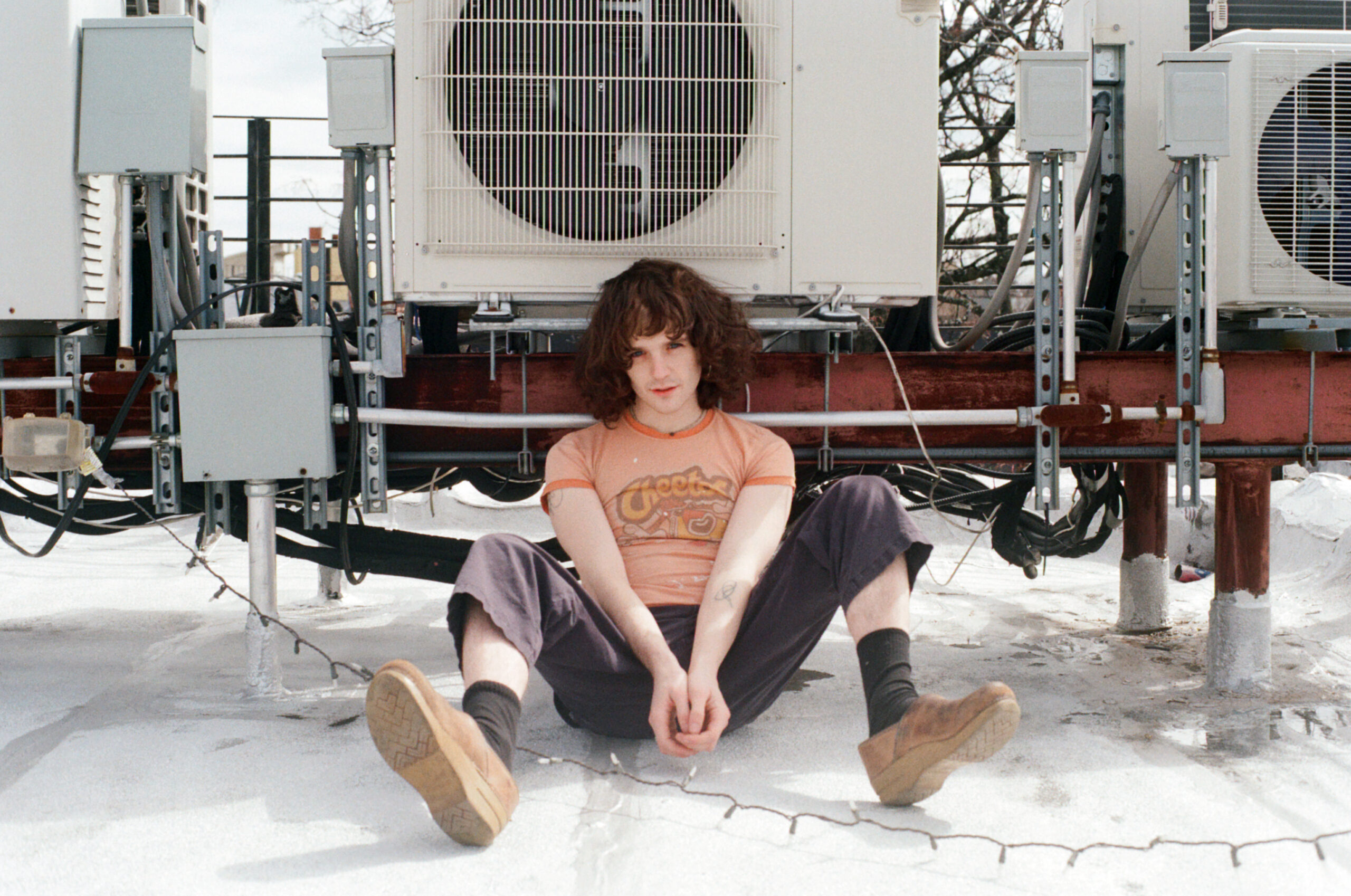

Flower Face is more than just a musician. Montreal's Ruby McKinnon has been building up the mythology around her upcoming album with Polaroids, drink recipes, a loveline, and poems. Girl Prometheus, the follow-up to her 2022 breakthrough The Shark In Your Water, is as intense and magical as its name suggests, containing 10 dynamic songs that explore the extremes of heartbreak and desire.

As a tween, McKinnon made intimate, lo-fi tunes in her bedroom. In the time since, she's had songs go viral and signed to a record label during the pandemic. Now at 26, her following is always invested in her next move and she never lets them down. Girl Prometheus is an enrapturing, turbulent odyssey with devastating lyrics wrapped up in fluttering string arrangements. The opener "Biblical Love" begins as an acoustic daydream as McKinnon whispers startling confessions: "I want to be untouched and clean/ Till you follow me home/ And you take that from me." After a minute and a half, the tame sound is ruptured, the song plunging into an dazzlingly unexpected violent outburst. Girl Prometheus is packed with similar twists and turns that encapsulate the treacherous motions of lovesickness.

Over Zoom, McKinnon told us about her musical history, the time she drank whiskey and screamed for Girl Prometheus, the allure of breakups as fodder for art, and her new song “Maniac,” out today. Below, watch the “Maniac” video and read our conversation.

You've been releasing music for around a decade. How did that begin, and when did Flower Face start?

RUBY MCKINNON: Pretty much the same time. I was always a writer from when I was really young, and I was always a big fan of music. When I was 13 or 14, I started writing songs, and I was really into Tumblr. I was very online at that point, and I got really into all these artists on Bandcamp and listening to their home-recorded work. I was like, “I could do this.” My dad worked in radio my whole life, so he had some recording equipment, some basic stuff at home, and he taught me how to use it. I basically wrote an album of songs that are not very good because I was 13 or 14, and then I just decided to release them on Bandcamp. I never really thought it would go anywhere. Then throughout the years, I developed this following from all over the world, which was really cool. Then I started doing it in a really serious way once I was 17 or 18, releasing it on Spotify and everything.

What were you like writing about at 13/14?

MCKINNON: Things I had no idea about. It was mostly fictional at that point. I was writing about heartbreak and grief and all of these things when I really hadn't experienced anything; I hadn't had any real relationships. But I think I listened to so much music and I read so much when I was younger that I was able to fictionalize these songs. It actually ended up being sort of prophetic in a way where now I look back at those songs and I actually relate to those, even though when I wrote them I had no idea what I was talking about.

Which musicians from Tumblr did you like?

MCKINNON: I remember following Nicole Dollanganger back then. We ended up actually becoming friends recently. We follow each other and we've messaged a few times. I would love to work with her at some point, but I remember watching her rise in the same way, like posting songs on Bandcamp, sharing them on Tumblr, and then she ended up with a pretty cool career. Also, I got really into Bright Eyes when I was 11 or 12.

You mentioned your dad worked in radio and I read that he showed you cool bands. Which bands did he show you?

MCKINNON: He actually introduced me to Bright Eyes. He worked at a radio station that eventually became more like radio alt-rock. But back in the day, they were premiering all the cool stuff. They were a Detroit–Windsor station because I'm from Windsor, Ontario, and so when Bright Eyes released “Easy/Lucky/Free” from Digital Ash In A Digital Urn he got a promo CD of it before it came out. I remember him playing that for me and my mom, but at that point I was like eight years old and I loved it. That was a song we would all listen to together in the car and then I got into them on my own when I was around 12. He introduced me to the National later, which became my favorite band. When I was younger, I grew up listening to Tom Waits, who was probably one of my biggest influences. Kate Bush, Tory Amos, Portishead, Tricky, lots of cool stuff. I owe most of my music taste to my parents honestly.

Hearing Bright Eyes at eight years old is crazy. It's like you were doomed.

MCKINNON: I know, I feel that way. I’m always like, “That's where the downfall began.” I think that's also why I was able to write about so many things I never experienced, because Bright Eyes have such a rich discography and Conor Oberst is so prolific that I was hearing all these songs and I'm like, “I totally know what it's like to do drugs and be sad. I'm gonna write a song about it now.”

These songs I put out back then, and they're not on Spotify or anything, they're all just on Bandcamp. I want to take them down, obviously, because they're so embarrassing now, but a lot of my fans still really love them. But I'll sometimes get comments on YouTube being like, “This sounds exactly like this song by Bright Eyes.” I'm like, “Of course it does. I was 14. I probably copied the song note for note. I didn't plan on this being something anyone heard."

I also read that you were a tween fangirl, and I'm curious of how it feels to go from being a fangirl to being a musician yourself.

MCKINNON: It's cool to be on the other side of it. When I was a teenager, I was going to all of these shows and waiting around after to meet the band for half a second and take a photo, and and it always meant so much to me, like that would stick with me for a year and I would write in my journal about it and I'd just be so happy. The thought that I could give that experience to people is really beautiful. And getting messages, kind of messages that I used to say — I used to write handwritten letters and give them to artists at shows — but the kind of things I used to say of how the music shaped my life and how it helped me process things and deal with things, and hearing that same thing about my writing is really a full-circle moment. I want to always stay connected to that gratitude that I had for other artists.

You signed with a label during the pandemic. Did that feel real?

MCKINNON: Not really. I signed my contract — I was with my family because I was living with my family during the pandemic — on a FaceTime call with my manager. We took photos of Laura, my manager, in the FaceTime on the iPad. After we could travel again, I ended up going and meeting a few people from the label in LA, but yeah it was strange. I also ended up sitting on my last record [The Shark In Your Water] for a long time because we literally finished recording it the last week of February 2020 and then everything shut down right after that. It didn't end up being released until 2022 so it felt odd because I'd written these songs so long ago, recorded them so long ago, and then I was releasing it — like this is all old to me, this doesn't feel very real in the sense that I feel like these songs have already been out. That was strange, but it was nice to have something to focus on.

The turning point for you is when "Angela" got traction online. What do you think it was about that song that moved people?

MCKINNON: I'm honestly not sure. It's funny, because I almost left that song off of the album that it was on; I wasn't certain about it. It was actually my mom — she loved it so much, and she was like, “You gotta keep this song.” I don't really know, but it is crazy because I wrote that about the first time I visited Montreal when I was 18 and then I ended up moving here because I felt so connected to it. So I feel like it's all very full circle, like it was meant to be. I think maybe because it is not necessarily a heartbreak song, but it's sort of a sad loss love song, but there is hope in it, which I think people like to connect to. It's like a book that’s devastating the whole way through versus a book that's really sad but then has a bit of hope at the end that you can hold on to. I think people like having a little bit of something to cling to at the end.

Your sound changed a lot between your last album and this one. The Shark In Your Water had a very eerie feeling, like Nicole Dollanganger's music. I read that you always aim for a big cinematic sound, and that's immediately what pulled me into Girl Prometheus. Why was that something that you were aiming for?

MCKINNON: I think I'm always drawn to music that sounds like that. I like feeling immersed in things. I like the drama, and I think it's so much fun to me because my writing process is so isolated. I'm writing alone with a guitar piano in my room. So the initial process is always very stripped-back. I don't have a band that we're throwing ideas around and making things sound big right away. So I've always just found the process so exciting, from writing the bare bones of a song to working on a demo and adding all these layers of synth strings and building it up and then going into studio and making it even bigger. I feel like that process is the most exciting part of music for me, so I keep going bigger and bigger.

Is it hard to keep making each new release sound even bigger?

MCKINNON: I haven't struggled with that yet, because each process has been a step up. I used to just record things at home by myself on my laptop. Then I was working with my friend Josh, who's a producer, in his home setup. Then I went into the last record in the studio, and then here did a bigger studio. We had an actual string section. It was a much bigger production. So it's made sense to this point, but I guess in the future there's only so far you can go with sounds within a certain budget, but I don't know. I always dream about being able to do live shows that have a whole orchestra and things like that.

I love the string section on this album. It sounds like a symphony.

MCKINNON: I actually arranged all the strings. Because we had a string quartet who were amazing, and we had them for like three hours, and we had nine songs to do. So my producer Marcus [Paquin] was like, “We got to be prepared. You just write chord charts if you want something simple. It would be good to have some ideas notated.” I have a classical background; I did classical piano, but I've never played a string instrument. I've never written for strings, but in four days I used a notation software and wrote string arrangements for nine songs, which is the craziest, most intense work I've ever done, but I'm so happy with how it turned out.

Especially because you also identify as a writer, I can't imagine writing something and then being able to put a whole string section on it.

MCKINNON: Yeah, it was very fulfilling. Honestly, so many parts of the recording process were really beautiful and exciting, but I think that was my proudest moment: When we were in the studio watching these players play these parts that I'd written, and I wrote them on Finale, a notation software that has built-in fake string sounds that sound so awful. So I'm writing these violin parts, and I'm like, “Oh, this is gonna sound so bad. I hate the violin. This is gonna sound terrible.” Then sitting there and hearing the actual musicians play, it was like, wait, this is actually beautiful. Me and Marcus were both there tearing up. Just a very proud moment.

I also noticed with the big cinematic sound, it mostly exists in the first song and the last song. I was wondering if that was intentional, like bookending it.

MCKINNON: I think so. The first song I really like does a sort of fake out, where it starts acoustic and it's what's expected of my music and then it breaks into this huge musical meltdown. Then the last song was actually the final song that I wrote for the album. I wrote it two weeks before we went into the studio. I kept telling my producer, “I feel like there's one more song.” We had these nine songs; I felt like there was one more and I just needed to find it. He's like, “Well, you better find it soon, because we're going into the studio next week.” I just had this image of: It needs to be the ending and it needs to be huge and it's going to be my stepping away from the feelings of the rest of the record and into the next phase of my life.

With the first song, I hear backing vocals of you screaming the words; I'm curious of how recording that was.

MCKINNON: I've never screamed like that before. I screamed in one song on my last record, but it was just one long scream; I've never screamed lyrics. So we recorded all the instrumentals in a studio in Montreal, and then for all the vocals me and Marcus drove up to this isolated cottage on a lake and it was just the two of us. We recorded all the vocals there because we wanted to get a full emotional, immersive atmosphere. At one point, he had to go back to Montreal to take his daughter trick or treating because we were there for Halloween, and I was there for a night. He was like, “I can set up the recording stuff if you want to mess around and do stuff while I'm gone.” So I did. I was recording a bit, and I'm like, “You know what? I'm gonna try screaming and see if I can get this.” And so I drank a bit of whiskey…

Not whiskey…

MCKINNON: Yeah, I was like, “I need to do shots.” I think it was actually some Fireball. The microphone is in the center of the living room and I went and stood on the couch and I just screamed my head off. I was like, “Oh my God. Someone's going to call the police. People are going to show up here.” The cottage was so isolated that no one showed up. And I was like, “Oh, no one showed up. I could get murdered here.”

And it was Halloween too.

MCKINNON: It was Halloween. I was there alone on Halloween, sleeping over, Blair Witch Project trees out this giant window. So I record a few tracks of the screaming. I was like, “Yeah, this sounds cool.” The next day, Marcus got back and I was like, “Okay, I need you to listen to this in the song. Don't listen to the isolated track. Please just listen to it in the song. And either you like it or you think it's stupid.” And he listened to it. I stood there in the kitchen just really nervous. He's like, “This is the coolest thing I've ever heard.” It's my favorite part of the song for sure.

It is very subtle; there are so many things going on in that song that it's hard to tell what's so good about it. I also wanted to talk about that song lyrically, because you’ve said it's about this idea of a love where you feel like it'll never be enough for you because an earthly connection can't satisfy you. I thought it was interesting to start with this idea that all love is kind of doomed.

MCKINNON: I think it's also because it's something I think I've struggled with my whole life — this idea when I've had very deep loves, but I always feel like I need it to be more, like there's something that I'm searching for. I think maybe that's the reason why my relationships have ended in the past, but this thought of: Maybe it's because I'm never satisfied, or maybe it's because I just need to find the right one that does fulfill these requirements. Then it's kind of like, “Am I crazy? Do I want to be conquered? Or do I want to conquer someone? Like, what is going on in my head?” So it sort of breaks down to this insanity where I'm screaming. I thought that set the tone.

And “Maniac” leans into being crazy. Are you playing with the crazy girl stereotype that is often pushed onto women?

MCKINNON: Yeah, I think “Maniac” is like that for sure. It's stripped-down, the most kind of simple and almost conversational song. But then lyrically, it's a little scathing. I think that one is about a reaction to having someone sit you down and tell you, “Here are all the things that are wrong with you.” And so it started being like, “Yeah, I know this about myself. I know I can be histrionic and annoying and impossible to deal with, but what about you?” It's sort of this idea that I can accept and acknowledge what's wrong with me.

For the music video, I also wanted to play into the idea of playing into someone's ideas of their worst version of themselves. So I'm sitting there like a little kid in front of the TV and literally mimicking this weird, creepy, uncanny version of myself and playing into this idea of like, “Oh, I'm such a maniac. I loved you too much.”

When did you realize that heartbreak was a special topic for you to use in your art?

MCKINNON: Like I said, I was writing about it before I'd even experienced it. I think because so much of the music that I listened to was focused on that, and I think also it's the most universal feeling. When you're in it, you're like, “I'm the only person who's ever experienced this because it's so painful. Everyone would die if they felt this all the time.” But it is something that everyone goes through, and each person's experience is unique but the core feelings of it are the same.

I think that I have struggled with the idea of a breakup album because it can feel almost embarrassing. It’s like, “Should I be writing about something more important? Am I just focusing on romantic love? I should be writing about something that matters more than this.” But then I think about all the heartbreak songs and albums that have meant so much to me. Also, writing this album kind of saved me. It was a way for me to survive. So if people connect to it and people like it, then that's great. But I really didn't write it for anyone else's approval. I wrote it in order to survive what I was dealing with at the time. I think that it's really beautiful. I think that it gives you the opportunity to turn those feelings of pain into something much, much bigger.

I think something I struggled with when writing so personally about my heartbreak was “Who's gonna care about this?” and just worrying that I'm oversharing, even though we're in this culture now where oversharing is something that everybody does.

MCKINNON: Yeah, it can feel so self-indulgent. I'll get that when I'm writing a song, especially if I'm performing a song on stage. I'll sometimes get in my head and be like, “Who cares? Why am I doing this? This is so embarrassing.” But, again, if you just think about all the art that you've connected to about heartbreak, it's like, “I'm adding to this rich kind of tapestry of of heartbroken souls.”

To the idea of writing about your heartbreak to feel better and make something out of bad feelings, do you also think you're trying to memorialize past relationships?

MCKINNON: I think so. And I think I have a tendency — or an ability, we'll call it — to romanticize or poeticize really mundane moments or things that aren't very significant. So I think even if I'm writing about someone in a way that's maybe not so nice, it is honoring it in a way, and yeah, memorializing, sort of like keeping these little time capsules. I can go back and listen and be like, “Wow, I can't believe I felt that way.” Or like, “Thank God I don't feel that way now.” Or “Wow, I hope that someday I feel that way again because it's so rich with emotion.”

Breakups can often be dismissed as childish when they're used as topics in art, especially if it's by a woman. How do you react to that narrative?

MCKINNON: Like I said, it's the most universal feeling; it's something we all connect to. It's something we all go through, and even if it can be embarrassing, and you can feel like, “Oh, this is not important,” it's gotta be because people — everyone around the world — is experiencing these same kind of feelings and emotions and it is important, and it can be staggering, and it can rip your entire life apart. When my big breakup that this album is about happened, I definitely felt like, “Oh, my life is over, everything is just shattered and torn apart.”

As much as it is a breakup album, I don't even think of it as being really about that person or about that relationship. It's not about my experience with one person, kind of barely about him at all. It's about myself and my feelings and my friends and my family and the people I met afterwards, and the other brief love affairs and obsessions, and the way my world expanded and unfolded through the heartbreak. Whenever you're writing about a breakup, you're often not really writing about the breakup itself. It's about the aftermath, which involves every part of your life. It's usually one of the biggest growth moments for us and we can totally evolve in a very short period of time because we're forced to because we're forced out of this comfortable state.

Have read the book I Love Dick by Chris Kraus?

MCKINNON: I haven't, but it's on my list.

I love the song “Cat's Cradle” — I thought you would love I Love Dick because it's also about obsession to the point of abjection and just being insane, but also using obsession as a way to uncover things about yourself that you didn't even know were there.

MCKINNON: Yeah, it can be very revealing. And again, when you're obsessing over someone, especially someone that you don't know, it's all about you. It's all about this thing that's going on inside your head; you become so immersed in your interior world, and if you don't let it devour you, then it can be a big learning moment, a big moment of self-revelation.

I noticed that you, along with making music, also have a podcast, you uploaded really pretty journals to your website, and you write poetry. Is it important to you to have a lot of creative outlets?

MCKINNON: Yeah, I think I need to be able to jump back and forth between things to avoid getting too entrenched in any one thing, then I go a little bit crazy. I went to school, I have a degree in Visual Arts, so I also paint and draw and do collage art and stuff. Especially with writing, I've been writing so much in the past year, it was important to me to — once I finished writing the album — be able to work on other forms of writing, so poetry and prose and things like that. I think it keeps my mind sharp. It keeps my creativity flowing to be able to go between things, especially when I'm when I get really blocked in any one area.

Girl Prometheus is out 11/1 on Nettwerk. Pre-order it here.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!