"FUCK! FUCK! FUUUUUUUCK!"

Those are some of the first words you hear on "Hell 99," an unusually abrasive highlight from Foxing's self-titled album. Those are also likely some of the words Foxing's band members exchanged with one another while making their self-titled album. Both in its creation and its output, Foxing is angsty, angry, and antagonistic. It contains some of their heaviest, most direct material and also their most exploratory and challenging; it sounds exhausted yet robust. Self-produced, self-released, self-engineered, and self-titled, it is the most potent distillation of what Foxing is.

So of course I'm gonna drive four hours to hear all about it from the band themselves.

After pulling up to their studio in Collinsville, Illinois, a suburb 20 minutes from Foxing's native St. Louis, I'm greeted by vocalist Conor Murphy outside. Just as I put my car in park after a long drive in late July from my home base in Kansas City, a trek that took me from western Missouri to just beyond its eastern edge, Murphy walks up to my driver's door, his feet shuffling along the makeshift gravel driveway. He cordially introduces himself as he walks me to the entrance of the house, a former church where Foxing recorded their new album.

Murphy gives a tour of the place, which consists of an upper and lower level, and it's strewn with all sorts of paraphernalia: a toy sword resembling the one he wields on the artwork for 2021's Draw Down The Moon, a glittering Pearl drum kit, a haphazardly placed ride cymbal with "BLISS" spelled out in duct tape on its surface, a random cat who wanders around the premises. Frankly, the basement is equally messy. They just finished making the music video for "Hell 99" down here, he tells me.

He guides me toward the studio itself, the room where Foxing was born. The three other band members – guitarist and producer Eric Hudson, drummer Jon Hellwig, and bassist Brett Torrence – are all seated on a couch in the middle of the room, and their manager (and former Early November guitarist) Joseph Marro sits in the corner on his laptop. We all get acquainted, and Hudson heads to a stool in the back corner of the room to make space on the couch for Murphy. There's a Majora's Mask hat on a rack right next to Hudson, and, being a big fan of the game, I ask who it belongs to. "It came with the studio," Hudson says. Hellwig clarifies that they found it stored with a bunch of weed.

After making some light small talk, one of the first things the band explains to me is how tense and argumentative they all were making this album. Things were especially rough between Murphy and Hudson. "I hated everybody in the band while we were doing it," Murphy says matter-of-factly. "And everybody hated me. It's never a smooth process at all." I sit in the producer's chair, and behind me, near the ceiling, are framed pictures of the cover art for the first four Foxing albums. He points toward the framed records, claiming that he can recall at least a few big fights the band had during the making of each. For this new one, Hudson considered quitting the band "a lot of times," but surprisingly, the band's working dynamic has never been better. In hindsight, Hudson looks back on Foxing’s creation as "pretty nightmarish at times," but they "came out of it in a better place than how it usually goes, which is that we came out of it." Without fail, they resolve the issues and make up with one another, and they recognize that the core reason they'll start yelling matches all the time is that they deeply, deeply care about this band.

The care that goes into this band isn’t exactly lucrative, either. DIY isn’t sustainable in any society plagued by the nefarious pitfalls of capitalism. So much is proven by the fact that Murphy has needed to work a construction job while writing this record and rehearsing for its upcoming tour. "We all work these little jobs so we can go on tour afterward," he says. "And we hate them, but we want to do this." Foxing are at a point where most bands would give up and settle down, but then again, most bands aren’t Foxing. Going about this process without a label’s backing may make things harder, emotionally and financially, but it also grants them all the creative freedom they desire. "Self-releasing is a huge aspect of it, not having a label that’s coming in and saying, 'You guys should do this, this, and this, and also we’re going to have your money, as well,'" Murphy continues. "Every aspect of it is very much contained between the four of us and Joe."

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!

If there's any sort of through line that keeps Foxing active, then it's their unabashed earnestness. In an age of irony and apathetic facades, it's refreshing to have a group of musicians that has consistently remained sincere about their work. "I think that there is a lack of earnest art being made," Hudson says. He's quick to bring up a critique that a fellow music critic, who shall remain unnamed, once made about this band: that they care too much. Murphy says it's "probably my least favorite thing ever said about us," and Hudson "was definitely mad about it." But then he gave it some more thought and realized that he had no rebuttal. Why did it make him so mad? "Because it's fucking true."

No one's doubting that Foxing is a theatrical, over-the-top endeavor. But they believe it's better to double down on something you genuinely, fully believe in than portray yourself as unfeeling or careless. Hellwig points to the tour for My Chemical Romance's The Black Parade where Gerard Way would make his entrance coming out of a casket. "I just think that's so cool," he says. "I understand you could say that's corny or that they're trying too hard. But would you rather walk onto the stage like a loser or get wheeled out in a casket and rise from the dead?"

Even the album announcement came with a full-on performance art piece. Taking place at High Low, an event space-meets-cafe in St. Louis' Grand Center Arts District, Foxing invited members of the national press to attend a Sunday evening conference during which they announced the new record and shared its lead single, the eight-minute epic "Greyhound." They actually invited these outlets, by the way, but none of them showed. I was almost the only journalist in attendance until I realized I wouldn't get back to KC until midnight, and I'd then have to wake up at the crack of dawn to make it to my day job in the morning. Fortunately, they assured me there would be a recording of it for me to reference later. But Foxing truly did not know who would be there and who wouldn't. Realistically, though, they had a feeling that no one would be there. "Andy Cohen might," Torrence chimes in. "He's from St. Louis."

In the video, you can glance at some of the names they've taped to foldable chairs in the audience: Pitchfork (two seats), Anthony Fantano, CNN, Animal Planet (yes, Animal Planet!), UPROXX, Brooklyn Vegan, GQ, The New York Times, and the very site you're reading right now, where I likely would have been sitting had I decided to throw sleep and practicality out the window. The entire genesis of this piece started with the press conference, too. In mid-July, I got an email from Foxing's publicist with the mysterious subject line, "an unusual Foxing opportunity." So, were they expecting Anderson Cooper to pull up? Was Wolf Blitzer going to get called in at the last minute if he posted a picture of himself getting drinks in Missouri?

"There's hope, and then there's expectation," Murphy explains. "It's trying to get rid of the expectation part of it and not assume that it's going to be a full place or an empty place. But if Anderson Cooper shows up, that would be really cool."

On the surface, the press conference may seem like a complete gag, like their own take on John Cage's "4'33." Yes, it's a bit, but it hints at something deeper, directly tying into the overall themes of the new album itself. "We've been doing this for a very long time," Murphy says. "What has it all meant? Has it all really been worth it? Does anybody care about it?" In this lens, the conference is partly a statement piece and partly a litmus test. Foxing had planned on this conference being one of the few pieces of press they do for this album cycle aside from this feature. It's where they'll get a lot of information and details about the album across. "It's supposed to be a reflection of us doing all of this ourselves," Murphy says of the idea for this whole shenanigan. "We're not trying to get across the themes of the record unless we're asked in the Q&A section by somebody. But if nobody's there…" His voice trails off.

In a bout of dramatic irony, we now all know that Marro moderated an empty room, and all four members of the band sat at the panel during a completely silent Q&A segment. Maybe Foxing really do care the most.

***

I decide to be upfront and ask them directly: What are the themes of the record?

"Nihilism to hopefulness," Hudson says. "Parts of it are about the idea of giving up vs. acceptance. Is giving up a bad thing? Or is it just a way of accepting something?" "Hell 99," specifically, reminds him of going online and seeing posts about recycled pop culture IP next to photographs of dead children. "Is this all there is? FUCK! FUCK! FUCK!" goes the main hook, its screamo kineticism eventually giving way to a dreamy, reverb-drenched outro.

Opening track "Secret History" contains a shred of optimism for the future, but it's also marred by the quotidian drudgeries of being forced to go to school or maintain a job. "Sharpen those dead dreams/ Pay them violently/ Write them quietly/ Secret history," Murphy sings, his voice rising to reach its upper register, before Hudson comes in screaming, shredding his larynx on the chorus: "Sold!/ The dreams!/ For arms!/ And legs!" The sudden spike in volume brings to mind other opening tunes like LCD Soundsystem's "Dance Yrself Clean" or Wednesday's "Hot Rotten Grass Smell." The band themselves mention Mitski's "Your Best American Girl" as a reference point. In terms of the album as a whole, however, it's "different episodes of feeling the ups and downs of growing up and realizing what the world is," Hudson says.

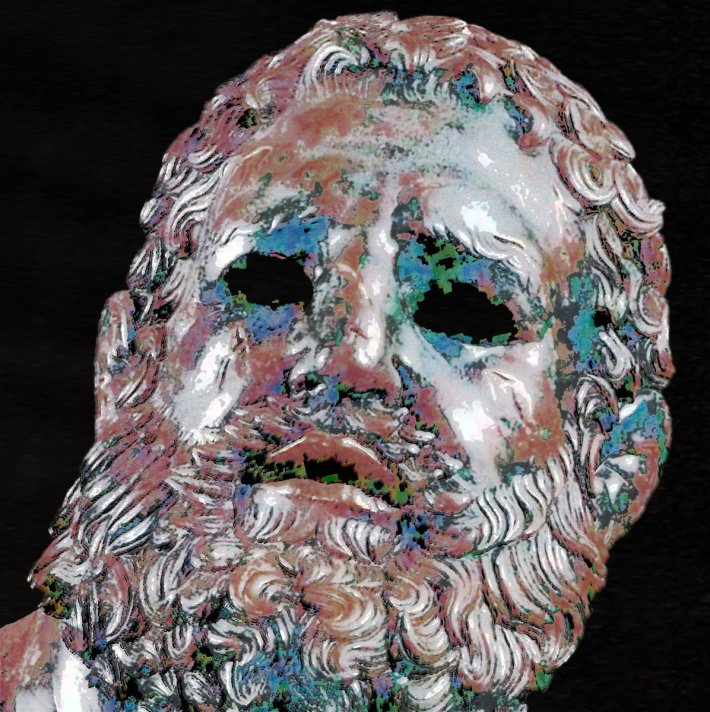

Torrence, who was a touring member for seven years and has now become the band's official bassist, has his own interpretation. "It's a little tricky for me to answer because I feel like I've been a part of this, in a real sense, for such a short time," he says. "But it seems like, thematically, the album was created in pieces, and there's a thread finally connecting it toward the end. It does focus on what Eric was saying earlier about self-sacrifice and personal time put into making this band work and exist." Alongside now being a formal member, Torrence also created the album art: a striking image of a hollowed-out, sculptural face.

While on tour last year, he read Thom Jones' The Pugilist At Rest, which then got him interested in the famous Hellenistic Greek statue Boxer At Rest. At the time of its creation, purportedly sometime between the late fourth and second centuries B.C., boxing was considered a prestigious art form. "The statue was really looking at the sacrifice that boxers put into it," Torrence says. "This guy looks beat to shit."

Foxing have been doing this for a long time now. After all, they're still somewhat fresh off of their co-headlining tour with fellow emo stalwarts the Hotelier, who were performing their influential 2014 album, Home Like NoPlace Is There; Foxing, meanwhile, were playing their debut, 2013's The Albatross, in full. The tour was meant to celebrate the 10-year anniversaries of both albums, and it made Foxing ruminate on all the time that has passed and how they've changed as both artists and people. "Especially coming off of a 10-year anniversary tour for our first album, it's like, we've been building this thing for a very long time that was always supposed to turn into our career," Murphy says. "You're working toward something just like any job; you're building something over a decade or more and then getting to a point with it where you're realizing, ‘Is it time to throw in the towel on this whole thing? Is that going to make our lives better if we did that? Or is this a moment where you push through and keep doing it?' It's an unanswered question because none of us have answered that question at all. But that's the reflection that's coming through on a lot of these lyrics."

Hudson has another salient thought: "Or it's like, your brain's turning into mush, unrecognizable to your friends that don't tour in bands and make music."

I ask everyone if the Albatross anniversary tour activated discussions surrounding the band's existence and longevity, whether it made them think about if they wanted to continue Foxing. Murphy, Torrence, and Hellwig immediately look toward the back of the room at Hudson, who is laughing to himself. "OK, it's hard," he says, still stifling some laughs. "It's hard because it's important to separate it. The shows, the people who came to it, and the people I was on tour with? Great. No issues. It was awesome. Totally no complaints, right?" Except there was a catch. "There were a lot of nights playing The Albatross where I had some of the darkest fucking thoughts I've ever had in my life." The old songs were bringing back memories, often unpleasant ones, that made Hudson reevaluate his life and career path.

There's also the fact that they don't even like every song on that album anymore. "I was 18 when I wrote a lot of the lyrics on that thing," Murphy says. "I was like, ‘This is so embarrassing. I hate these lyrics so much.' But I had to sing them with conviction and energy and try to put myself back in an 18-year-old's mindset. You can do it for one song in the context of a set where there are new songs, but doing the whole album, and looking out to a crowd of people…" He continues: "I completely understand why people go to these anniversary shows. We all want to see Pixies do Doolittle and Weezer do Blue Album. You don't really want to see new Weezer or new Pixies."

But the difference is that Foxing are still making vital, urgent music that stands toe-to-toe with some of their best work, whether that's The Albatross or 2018's Nearer My God. Incidentally, Hudson quips that the Nearer My God 10-year anniversary is slowly sneaking up on them, which Murphy quickly shuts down. They "definitely learned we'll probably never do an anniversary tour again."

This band has managed to evolve its sound overtime, rather than reaching a dull, predictable complacency. The Albatross placed them within the "emo revival" wave with contemporaries like the Hotelier, hence the joint anniversary tour. Twinkling guitars and emotive vocals abounded, eventually traded in for more spacious arrangements on the post-rocky, darker follow-up, 2015’s Dealer. Such a move likely alienated them from the rest of emo’s fourth-wavers, but it was a bold switch-up that firmly placed them in a league of their own. Sensing newfound isolation, the group indulged their wildest, loftiest ambitions on Nearer My God, an unapologetically zealous LP that leveled up their sound in just about every fathomable facet, the nine-minute "Nine Cups" being a memorable centerpiece. Draw Down The Moon, produced by Manchester Orchestra frontman Andy Hull, may have polarized some fans with its post-Passion Pit synths and poppy choruses, but Foxing were still doing something different. Never a band to rest on their laurels, they tried something new. Whether it worked for you or not, it most certainly didn’t repeat its predecessor.

And not to make any sort of impetuous judgments on a still-new record, but Foxing might be their best work in an already impressive discography. It feels pretty on the nose that the album is self-titled, given that this was made solely by the four people in the band, save for some electronic flourishes courtesy of their close friend Ian Jones, aka St. Louis producer Shinra Knives. If there is any kind of overarching narrative, then it's the fact that this is an album about Foxing as a band.

All four members collectively agree that this is the only thing they can envision themselves doing in the long term, despite the many, many heated arguments it spawns. Hudson likens it to creating a character in an RPG. "It's like I put all my skill points into this one fucking thing, and I'm really good at that thing." But, as Hellwig clarifies, "it's really difficult for any of us to reroll those skill points." Despite the fact that everyone in the room can point to a specific song that nearly wrecked the band, the one called "Gratitude," of all things, Foxing aren't going away anytime soon. "That song ruined my life," Hudson says, half-joking. He was fighting to exclude it from the final tracklist, but the rest of the band insisted that it should stay. It took him five days to mix it, instead of the usual one or two. "I did hate-mix that song," he says. Simply put, he didn't understand "Gratitude" at first, so he chiseled away at it until his brain could process it, until he could make it the best it could be. But the moment that speaks most effectively to Foxing's grueling creative process comes in the track that directly follows it, and it's a moment that doesn't sound grueling at all.

Toward the end of the album, during closing track "Crybaby," a voice recording surfaces from a wash of ambience. "I don't think the song is as good as it could be, but it's coming along," it says. The speaker is a prepubescent Hudson, talking about the very first band he was in with Murphy, using an iRiver MP3-player's voice record function. Hudson is the clear perfectionist of the group, who will mix a song for days on end until, in his words, he "unlocks" it. The 13-year-old version of him in that recording may as well be speaking to his current-day self. "I really love that voice clip because it reminds me of when I started doing all of this," he says.

It's rare to find an instance of a middle schooler giving their bandmates constructive feedback because a song doesn't live up to its potential, and Hudson hasn't changed much in that aspect. "It sounds like you could have recorded that yesterday," Murphy jokes. Even after an album that questions the purpose of being in a touring indie rock band – and the taxing strain it has on relationships with family, spouses, and the band members themselves – it's a reminder about why it's all worth it. It's a reminder of why they're all still doing this, even if they outright despise one another from time to time. "As frustrating and exhausting as it is, I'm happy about it because I'm doing the thing I always wanted to do since I was a kid," Murphy says. Foxing ends with the innocence of how Foxing began: in total earnestness.

Foxing is out 9/13. Pre-order it here.