Forty years ago, David Byrne danced with a lamp. In what might be the most memorable scene of Stop Making Sense, my pick for the best live-concert film ever made, Byrne picks up a regular floor lamp, previously a mere part of the stage setting, and pushes it back and forth, shimmying all around it -- a classic subversion of pop-star gesturing that works as pop-star gesturing in its own right. On Friday night at Merriweather Post Pavilion, Mitski did Byrne one better: She danced with a beam of light.

Mitski was never alone onstage, but she was also always alone onstage. On her current tour, Mitski's eight-piece backup band -- including Patrick Hyland, her longtime producer and musical director -- stand in a V formation on the sides of the stage, off in the shadows. At the center of the stage is a circular riser, and that's where we find Mitski. Tonight, she's in a white shirt and some extremely sparkly pants, and her hair is short. She's the only person on that riser all night, but in this moment, she treats a shimmering spotlight as her dance partner.

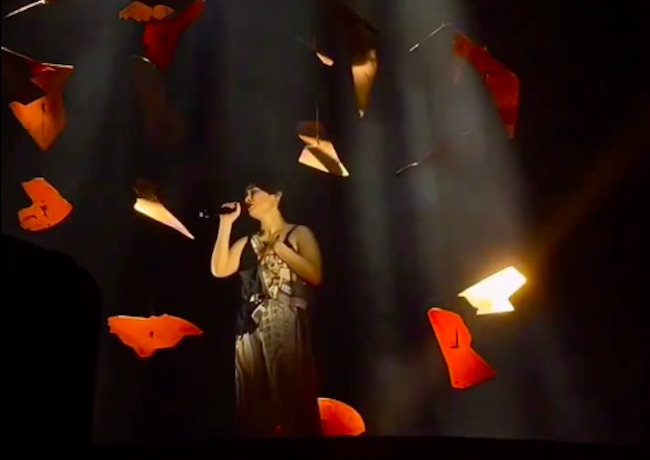

It's two spotlights at first. Mitski sings "Heaven," from her most recent album The Land Is Hospitable And So Are We, while weaving between those two spotlights, lightly chasing them around the stage in a genteel abstract-slapstick setpiece. Then the two lights merge, and Mitski wraps her arms around them, waltzing them across the stage. As a spectacle, it's strange and disorienting and at least a little bit beautiful. There's a lot of that at the Mitski show.

I swear that I didn't think of David Byrne just because Mitski once sang an Oscar-nominated duet with him. Byrne and Mitski are both wonderfully strange stage presences whose shows work in ways that exploit the already-unnatural relationship between performer and audience. Much like Talking Heads in 1984, Mitski is just now tickling the edges of mainstream stardom after years as a cult sensation. It's probably too reductive to say that she's like if David Byrne was more of a David Lynch type than a Jonathan Demme type, but I'm saying it anyway. Her transition to actual fame has been rocky and reluctant, but it's been absolute. She is now fully capable of packing Merriweather, a venue of a capacity near 20,000, for a three-night stand over Labor Day weekend.

mitski performing at the merriweather post pavilion in columbia, maryland on 30th august 2024

merriweatherpp pic.twitter.com/8dtmChvKgd

— ຸ (@MitskiCentral) August 31, 2024

Mitski's rise to quasi-pop stardom is about as unlikely as it gets. I thought I was late to Mitski. My Stereogum coworker James Rettig was a big proponent of Mitski's early self-released music, but I didn't jump on board until 2016's Puberty 2, which was album number four. When Mitski toured behind that record, I saw her play in front of a few hundred people in my local college town, and I thought it was cool that she could bring that many out. Back then, Mitski was a reserved, slightly distant stage presence, and her flirtations with larger fame seemed awkward and tentative. A friend of mine was on the 2018 Lorde tour that Mitski opened, and he was worried about how it must feel to play her skeletal, ultra-personal songs to crowds that simply didn't care. Now, Mitski draws more people than Lorde did back then.

I can't really explain what happened between then and now, but Mitski became a star. She's a viral phenomenon, but not because of any one particular song. Instead, Mitski's entire catalog has taken off. Some songs are bigger than others, and last year's "My Love Mine All Mine," which became Mitski's first-ever Hot 100 hit, has more than a billion Spotify streams. But there are tracks on nearly every Mitski album, going all the way back to 2012's Lush, with hundreds of millions of plays. (The one exception, weirdly, is 2022's Laurel Hell, the album where Mitski probably came closest to courting something resembling mainstream fame.) Mitski has achieved all this while staying independent, largely keeping away from social media, and refusing to play any kind of fame game. She is a great, glittering exception to every possible music-business rule.

My daughter is a big fan. To her, Mitski is no different from Chappell Roan or Lana Del Rey -- an emotional "sad girl" songwriter who makes music that she plays on endless repeat while she's in math class. (At least in her school, they let kids listen to headphones in math class. Can you imagine? I was born at the wrong time.) Judging by the Friday-night crowd, lots of people's daughters are Mitski fans; my kid and I were clearly not the only dad/daughter pairing in the building. But the crowd doesn't act like most big-pop crowds. Last year, in the same venue, Clara and I watched Lana Del Rey get the full scream-along singalong treatment. People don't do that for Mitski. People know better.

The parasocial relationship between Mitski and her fans has become a point of major conversation. A few years ago, Mitski openly considered quitting music entirely, and the thought seems to cross her mind again every few years. She's gone on record asking fans to keep their phones away at shows, to remain in the moment. In a viral clip earlier this year, someone between songs yelled, "Mother is mothering!" and the entire audience groaned and yelled for that person to shut up. Complaining about crowds at Mitski shows seems to be part of the deal with being a Mitski fan. Maybe that's why her reactions are so strange now.

Pop-star reactions are always strange, and they must be both alienating and gratifying for the pop star human beings themselves. At Merriweather, Mitski's fans screamed when she came onstage and whenever she took a moment between songs. This wasn't applause. This was Bieber-level hysteria. But then they'd all quiet down when she started singing. In the seats under the roof, everyone remained seated for the whole night. Nobody even got up to dance when it would've been musically appropriate to do so. (As a rapidly aging man whose body is in active revolt against his showgoing habits, I appreciated this.) When Mitski sang one of her quasi-hits, the phones came out. The rest of the time, people just attentively watched and listened. What a concept.

A Mitski live show rewards that attention. For one thing, she doesn't just come out and sing the hits. Plenty of her biggest songs -- "My Love Mine All Mine," "I Bet On Losing Dogs," "Nobody," "Washing Machine Heart" -- have places of honor in her setlist, but the big numbers are not guaranteed. Mitski mostly didn't play the songs that rock hard; we got no "Your Best American Girl." Many of the songs got countrified makeovers. The arrangements were full of acoustic guitars and pedal steel, and they sometimes veered into oddly jazzy Western swing. For I forget which song, Mitski went with an otherwise-minimal arrangement with one guy going ham on zydeco accordion. Mitski keeps total control over her expressive voice. With an expert band behind her, the live versions of her earliest songs were often a whole lot more layered and finished-sounding than the renditions captured on record. In person, those songs sound incredible.

But the visual side of Mitski's show is what's going to stick with me. She's been incorporating artistic choreography onstage for years now, and I truly had no idea what she was going to do at any given moment. Before Mitski arrived, a giant billowy curtain hung at the center of the stage. Mitski made her entrance from the side and looked up at the curtain, as if to say, "Huh. A curtain." Then, and only then, she went behind it for the big-silhouette business and the dramatic drop, undermining certain rituals even as she indulged them.

My brother flew out from St. Louis for the show, and at one point, I turned to him and said that Mitski was making me think of Austin Powers. He scoffed and said that no, what was I talking about, she's way more intense than that. Mere seconds, Mitski broke into a wild, arm-flailing frug, as if she'd heard what I said and she was determined to prove me right.

mitski performing washing machine heart at the merriweather post pavilion in columbia, maryland on 30th august 2024

cdluvah pic.twitter.com/htokuxcAqH

— ຸ (@MitskiCentral) August 31, 2024

You cannot look away from what Mitski does up on that stage. At one point, she sits in a chair and plays still, graceful air guitar for an entire song. I've seen Mitski play actual guitar, so I know she can do that, but that wasn't the moment of theater that she had planned out. During "I Bet On Losing Dogs," she got down on all fours, panting and swiping at the air. Later on, shards of glowing brass descended from the ceiling on long strands of rope, surrounding Mitski while she sang. When it was time for them to go, Mitski raised her hand under each individual rope, and it rose back up. When all the ropes went away, she looked up and waved them goodbye.

mitski performing at the merriweather post pavilion in columbia, maryland on 31st august 2024

ainsleysbowl pic.twitter.com/BHrkvdsXWX

— ຸ (@MitskiCentral) September 1, 2024

I caught myself wondering: Is Mitski's big-room live show a commentary on the nature of glamor? Or is she actually glamorous now? Is there a meaningful distinction between those things? Probably not. In the rare occasions that she talked to the crowd, Mitski kept mentioning the introverts in the house, thanking them for their presence and rhapsodizing about the miraculous power of all these people pushing themselves hard to be in this place on this night. Maybe when she's up onstage, Mitski is giving an artistic introvert's take on the alien pantomime of pop stardom. Out in the crowd, however, Mitski is a pop star, no qualifiers necessary. What a thing to be.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!