- 679

- 2004

These days, it's possible for a pop star to move like an indie band. Whereas someone like Carly Rae Jepsen might've been written off as a one-hit wonder a generation or two ago, she's spent her post-hit career touring clubs and festivals, playing to audiences who aren't just there to hear her one hit. Last year, the critic Shaad D’Souza wrote a New York Times piece about the middle-class pop star, a category that seems to grow more crowded every day. The term fits avant-pop critical sensations like Caroline Polachek and Rina Sawayama, but it applies just as easily to singers like Rita Ora and Ava Max -- permanent also-rans whose down-the-middle dance-pop never quite broke through but who have nurtured culty fanbases of their own anyway.

If anything, the mainstream-pop underground of today is more verdant and exciting than just about any scene that revolves around guitar-based rock music. Over the past year, plenty of stars who spent years lingering on the fringes of the pop world -- Charli XCX, Sabrina Carpenter, Chappell Roan, Tinashe -- have made tremendous cultural waves and moved up in the world. That's the trajectory that critically beloved rock bands once rode. But even when pop singers don't have those big mainstream breakthroughs or comebacks, they can often carve out comfortable careers for themselves.

The great Pop Pantheon podcast has coined the term "niche legend" for the pop stars who never quite become actual stars. The culty pop artists of today often name Robyn as their key inspiration, and the shoe fits. In the late '90s, the Swedish teenager Robyn made a few glittering global hits with a pre-Britney Max Martin. Robyn then disappeared from the major-label system, came back as the head of her own label, and returned with records full of alternate-universe pop hits that eventually became just as beloved as real pop hits. But when American rock critics started going nuts for Robyn in the mid-'00s, she seemed to be following in the footsteps of another blog-bait Scandinavian singer. Annie walked so that Robyn could run.

When Pitchfork's parent company laid off much of the website's workforce last year, plenty of the premature obituaries came from online nostalgists who remembered the publication as a champions of indie bands like Arcade Fire and Animal Collective. But in 2004, the arguable peak-Pitchfork year of Funeral and Sung Tongs, the site's #1 track of the year was "Heartbeat," a swirling and starry-eyed single from the Norwegian singer Annie. Writing about the song, Scott Plagenhoef, then Pitchfork's editor in chief, coined the term "fluxpop," clearly named in honor of Fluxblog, Matthew Perpetua's pioneering MP3 blog. Plagenhoef defined fluxpop hits as "tracks with a pop sensibility and communicative, crossover potential that are nevertheless more often transferred via 0s and 1s than Hot 97s or Radio Ones," and he put Annie at the top of a class that included names like M.I.A., the Knife, and the Scissor Sisters. Today, that definition could apply to any pop star. Now that we all access new music on our phones, radio is obsolete, and fluxpop reigns. We just call it "pop" now.

Annie did not invent this kind of pop. On Pitchfork's list of 2004's best pop tracks, "Heartbeat" sat right above Jay-Z's "99 Problems," Britney Spears' "Toxic," M.I.A.'s "Galang," and LCD Soundsystem's "Yeah (Crass Version)" -- so much for the idea that critical poptimism is a recent development. James Murphy voice: I was there. 2004 was the year that I started writing for Pitchfork, using my office computer to bang out reviews of Lil Scrappy and Ciara tracks because I didn't have a computer at home. I was part of a wave of writers who were just as excited about the power of three-minute pop songs as we were about, like, the Walkmen. Whenever he'd write about Annie, Scott Plagenhoef would use her almost as an avatar for the idea that pop music could, and should, be as great and powerful and transformative as anything made with your standard guitar-bass-drums setup. Some of us believed this fervently. Some of us still do.

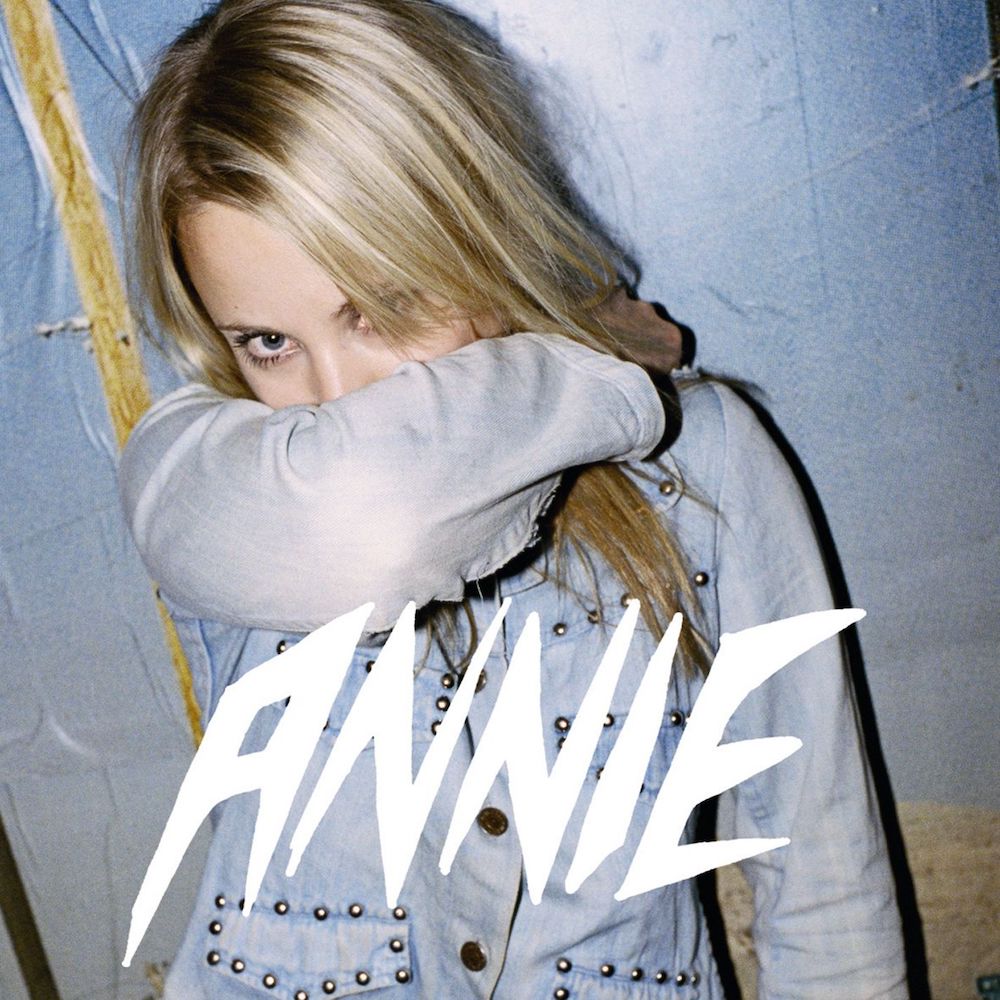

Given that Annie was a pop singer who wasn't actually popular in most of the world, the conversation around her created a strange divide. This singer made these strange, glittering nuggets of melody, but her American record sales probably weren't even in the Califone zone. There was precedent for this kind of thing. Early in her career, Annie opened shows for Saint Etienne, the British art-pop duo whose club-friendly sophisti-pop yielded actual chart hits in the '90s. In the early '00s, the electroclash phenomenon riffed on the aesthetics of big-money dance-pop, turning its headset mics and confetti-cannons into weapons of coke-addled irony. But Annie wasn't necessarily an arty conceptualist who took on pop stardom as a pose. Instead, she simply made pop music because she loved it. Stardom, even of the middle-class variety, never quite followed. But for a moment, the American press treated Annie as if she was an alien representative from Planet Pop. The context surrounding Annie's debut album Anniemal, which turns 20 tomorrow, is enough to drown out the music itself. Thankfully, however, the music holds up.

One of the things that attracted American critics to Annie in the first place was the backstory -- the same kind of thing that gets us excited about rock bands. The backstory was this: Anne Lilia Berge Strand grew up in the coastal town Kristianland before moving to big city Bergen as a teenager. There, she briefly sang for an indie band, DJ'd in clubs, and started dating another DJ: Tore Andreas Kroknes, who went by the name Erot. One day, Annie played the classic early-Madonna banger "Everybody" for Erot. He built it into a sample, and the two of them wrote a song around that sample. The resulting track was "Greatest Hit," a shits-and-giggles dance-pop anthem about the power of music itself. In a soft and halting delivery that owed more to UK twee than to mainland-Europe superclub music, Annie sang dazed, romantic broken-English lyrics about what happens when music makes the people come together: "We dance and groove in the disco lights/ I want you alone with me tonight."

Annie and Erot got a friend to press up a few hundred vinyl copies of "My Greatest Hit" in 1999, and the song made its way through cool-kid circles, first in Norway and then in the UK. Labels sniffed around, and Annie and Erot began to entertain the idea that they could make pop music full-time. But Erot had a heart condition, and while "My Greatest Hit" started to spread, he was in and out of hospitals. He died in 2001, only making it to the age of 23. Annie, deep in the throes of depression, stepped away from music for a while, but then music became the way to cope with her loss. She got together with Timo Kaukolampi, from the arty Finnish dance group Op:l Bastards, and started making new tracks that built on what she'd already done with "My Greatest Hit."

In the early '00s, Annie made another important connection when the British producer Richard X fell in love with "My Greatest Hit" and invited her to collaborate. Richard X made his name putting together bootleg mash-ups that got lots of burn on nascent MP3 blogs. Under the name Girls On Top, Richard posted a track called "We Don't Give A Damn About Our Friends," placing the lyrics from Adina Howard's raunchy 1995 R&B smash "Freak Like Me" over the buzzing, clanking instrumental track from "Are 'Friends' Electric," the 1979 early synthpop classic from Gary Numan's old group Tubeway Army. That mash-up became a big enough underground hit that the Sugababes, an already-popular British girl group, recreated it as a proper single, with Richard X on board as producer. The resulting single was a #1 smash in the UK.

Richard X went on to make legitimized mash-up hits with artists like Kelis and Liberty X, and he got Jarvis Cocker to sing over a "Fade Into You" sample on his 2003 major-label album Richard X Presents His X-Factor Vol. 1. While working on that album, Richard X brought Annie in to sing on the track "Just Friends," and they kept working together for years. Richard X and pop songwriter Hannah Robinson co-wrote two tracks, "Chewing Gum" and "Me Plus One," for Annie. "Chewing Gum" became a top-10 hit in Norway, and it reached the top 40 in the UK. In America, that song didn't do anything commercially, but it was sticky enough that critics and MP3 bloggers fell in love.

Anytime you've got a pop song that's about gum, you're working on some kind of meta level. "Chewing Gum" winkingly acknowledges its own bubblegum status while using gum -- sweet, flavorless, disposable -- as a metaphor for a relationship that's not built to last. Richard X's production artfully layers '80s-style synth-beeps, vocoder burps, and funky bassline struts, while Annie playfully delights in her own heartbreaker status, happily chiding herself for turning another hopeless guy's head: "Hey Annie! Well, look at you! Is that a new boy stuck on your shoe? Come on, Annie! How is it so you've always got a new bubble to blow?" Among American critics, part of the mystique of "Chewing Gum" was the idea that a song this weird and layered was an actual pop hit somewhere in the world. America had its own weird, layered pop hits -- see: "Toxic" -- but it was fun to think about this song bumping out of car stereos on the other side of the world.

That same magic is all over Anniemal, which Annie mostly made without the help of British bootleg-DJ types. Op:l Bastards' Timo Kaukolampi produced most of Anniemal, cowriting tracks with Annie, while Röyksopp, the Norwegian duo who'd known Annie since her club-DJ days, helped out on a few more tracks. The full record has a consistent sonic identity that springs straight from "My Greatest Hit." It's a sleek-but-homespun take on the kind of mutant post-disco that Madonna made in the early '80s, filtered through a sharp Scandinavian melodic sensibility and delivered in the kind of downcast register that wasn't all that far removed from, say, Belle And Sebastian.

Annie never sang with the brassy authority of a Robyn, which is probably one of the main reasons that Robyn ended up headlining Madison Square Garden and Annie did not. In keeping with Euro-pop tradition, Annie sang English-language lyrics so simple but syntactically mangled that they sounded charmingly alien: "You're so tricky tricky/ Yeah now, Mister Wicky/ Now it's been an hour, make me feeling freaky freaky." But Annie's whisper-sing vocal implied elegant heartbreak, and her story confirmed it. Even at its silliest, Anniemal hinted at the kind of implacable yearning that could never be resolved.

When Pitchfork chose "Heartbeat" as the best single of 2004, you couldn't even hear the track through legitimate means in America. YouTube and Spotify didn't exist yet, and 679 Recordings, the British label that added Annie to a roster that included the Streets and Death From Above 1979, didn't put a lot of muscle into promoting the album. Anniemal wouldn't come out in the US until 2005. Since we couldn't buy the album, we had to use other means to hear it: MP3 blogs, file-sharing sites, Other Music import copies. That scarcity probably helped build buzz. In 2006, I went to see Annie play what I believe was her first New York show at the Mercury Lounge, a venue that played a big role in that era's hype circuit. I don't remember too much about that show, and the Village Voice blog post that I wrote about it has been swallowed by the internet ghosts. Mostly, I just remember hanging out with my critic friends that night, having a great time.

Annie never had a viral moment like the one where Lena Dunham danced on her own to "Dancing On My Own" on Girls. The critics' love of Anniemal didn't extend to the public at large, and Annie didn't have enough of a mainstream-pop profile to land in the kind of alt-pop stardom that now sustains a figure like Tove Lo. The category simply didn't exist yet. Instead, Annie signed a deal with Island Records, and it evaporated when her 2008 single "I Know UR Girlfriend Hates Me" failed to do big numbers. Good song, though.

Annie sophomore album Don't Stop finally came out in 2009 on the Norwegian label Smalltown Supersound, and she's continued to put out occasional work on smaller labels -- a 2013 EP with Richard X, the 2020 album Dark Hearts. Those records are good, and they got good reviews. Annie continues to quietly release impressive music. Earlier this year, she sang on the Alan Braxe track "Never Coming Back" and released her own single "The Sky Is Blue." But those songs haven't shifted the conversation around pop music. Annie already did that, and all of today's critically beloved niche legends owe her a thank-you.