Every few years, someone on social media posts a clip of one of the strangest late night musical performances to ever grace American televisions. "They make a tremendous amount of noise," Jimmy Kimmel deadpans, just barely preparing his audience for Seattle art-punks the Blood Brothers. After an initial squall of feedback, drummer Mark Gajadhar begins pounding his snare, and the band roars to life. Singer Johnny Whitney immediately launches into a high-pitched squeal followed by a full-throated scream — he sounds like a chipmunk in the jaws of a snake. He whips his mane of chestnut hair around wildly as he shimmies across the stage. His co-vocalist Jordan Blilie, meanwhile, stalks the stage with the stiff gait of Frankenstein’s monster. "Take me to the pit of celebrity pregnancies," he screams on the chorus. "I wanna wear the skin of a magazine baby!" Not exactly your typical late-night performance.

Whether you first saw them on television or at a hole-in-the-wall DIY venue, the Blood Brothers might’ve changed your life. In an almost exclusively white punk scene, here was a band with people of color among its members. While machismo was long the norm in hardcore, the Blood Brothers found terror in the effeminate. They rocked skin-tight Diesels far before skinny jeans became the norm and pranced around the stage like pop girlies from hell. Their music was abrasive, chaotic and confrontational but also complex, catchy and subtly political. For some of us who never quite fit in anywhere, they were a lifeline — a sign that there was a weirder, more interesting world out there waiting to receive us.

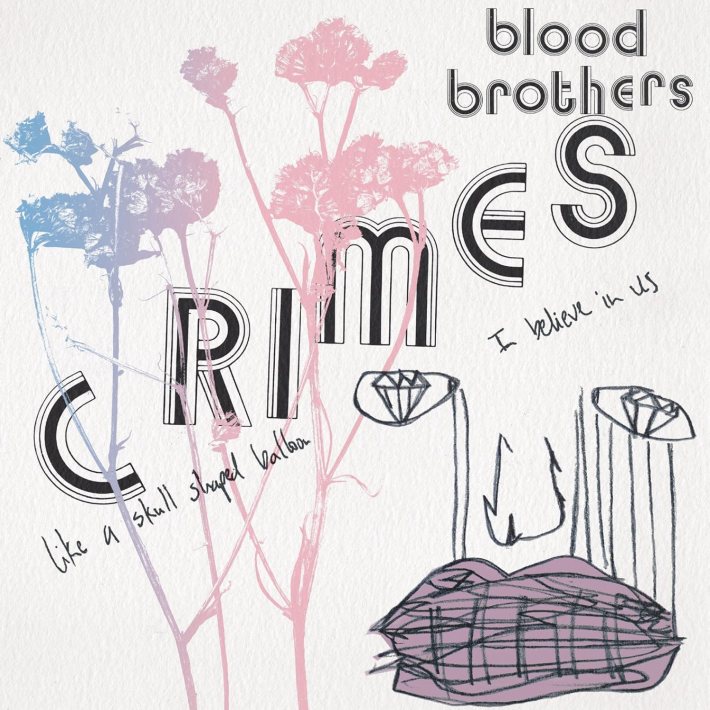

Starting in November, the Blood Brothers head out on tour together for the first time in a decade (though they disbanded in 2007, they briefly reunited in 2014 for a handful of performances). Before the tour kicks off in earnest, they'll make their grand return to the stage less than two weeks from now at the Best Friends Forever festival in Las Vegas, filling in for Bright Eyes as Sunday night headliners. These reunion gigs are meant to coincide with the 20th anniversary of Crimes, the band’s second album for a major label and fourth album overall, which will reach that two-decade milestone on Oct. 12. Epitaph is reissuing the album this Friday, part of a series of Blood Brothers reissues that began last year with ...Burn, Piano Island, Burn.

Even though the Blood Brothers were deepening their engagement with the mainstream music industry at the time of its release, in some ways, Crimes was their strangest record yet. Here the band slowed down their breakneck tempos, allowing the songs to sink into unsettling grooves. "Love Rhymes With Hideous Car Wreck" is a morality play sketched out by pleading — dare I say soulful? — vocals. "Peacock Skeleton With Crooked Feathers" is a twisted cabaret anthem built around a carnival organ line. "My First Kiss At the Public Execution" marries America’s history of barbarism with rosy-cheeked 1950s romance. Few of their peers in the West Coast screamo underground could have dreamed up a record like Crimes, an album which, paradoxically, brought the Blood Brothers within spitting distance of mainstream success.

Onstage, the dueling vocalists Whitney and Blilie were eternally each other’s foils: Blilie, a creepy vaudevillian straight man anchoring Whitney’s wildly flamboyant performances. Reached by Zoom two decades later, they almost look to have traded places. Blilie calls in from a room he is sharing with his five year-old daughter, who adorably interrupts to ask for assistance with her Disney princess figures or to chastise Blilie any time he slips up and drops an F-bomb. Whitney, meanwhile (who to be fair, is also a dad) calls in from a quiet, all white room with a stack of keyboards sitting behind him—presumably used for his day job as a software engineer at Netflix. In conversation, Blilie chooses his words carefully and waxes philosophical about the band’s songwriting process and influences while Whitney speaks openly and is quick to address his regrets when looking back on the band's run.

2024 Reunion Shows

I wanted to start out by asking you about the reunion tour. Why do more shows now?

JORDAN BLILIE: It was a couple of years ago when Epitaph started to talk to us about doing vinyl reissues of our last three records. So starting with …Burn, Piano, Island, Burn, then Crimes, and they're going to do Young Machetes next. It obviously got us all talking again. Not that we were in any state of like, cold war or anything like that — it just gave us a reason to be on the group chat again. And just talking about those past records and that period in our lives and sort of reminiscing, it was something that kind of popped into my head.

Having done those shows about 10 years ago, I had such a great time with that experience. But I felt that there was more that we could do. I think we only did like maybe five or six shows. There's a lot of work and a lot of prep that goes into getting yourself back to a place where you can play hardcore music with the appropriate amount of energy behind it. And so to do all that work and then play just that handful of shows…I always felt like maybe we could have done a little bit more. Maybe it would have been nice to play some of these other cities that we didn't get to hit up.

JOHNNY WHITNEY: I stopped playing music about 10 years ago and became a software engineer — I've been working at Netflix for almost 10 years now. And as part of that I go down to LA — I live in the Bay right now, but I go down to LA probably three or four times a year for work. And over the past five years, I've used it as an opportunity to go and get drinks and reconnect with Jordan and Cody [Votolato, guitarist], since they both live down there. I want to say this has been a long time in the planning — we first started talking about it in like, the winter of 2022. We all sort of have civilian jobs at this point other than Morgan [Henderson, bass], who's in Fleet Foxes. So the main thing we were kind of wondering is, would there ever be a break that would be enough time for us to actually even do a reunion tour?

I just really miss those guys. We grew up together. I met Jordan the first day of 7th grade — I've known them for over 30 years. And it's harder at this stage in all of our lives to really reconnect with each other unless we have something that we're doing together. I mean, I'm closer to them than I am with, like a lot of my extended family.

BLILIE: Also, I think it's safe to say that Crimes is the majority of the band’s favorite record that we did, so that is the one that made the most sense to plan shows around.

You mentioned the physicality of playing hardcore shows and getting yourself to a place where you can do that again. I was lucky enough to see you guys during your initial run and the intense physicality of the shows is something that really stood out to me — is the idea to try to recreate that?

BLILIE: I think that you have to…it's a genre that requires that sort of communal physicality — that's what's so powerful about playing a hardcore show. So when you take that out of it, it just feels like something integral is missing. When you do a reunion show, you're doing it primarily for the audience who grew up seeing you and then also for those people who maybe got into your band later and didn't get a chance to see you. I feel that there's a responsibility to honor the memory people had of seeing our band and to honor the expectation of those who didn't get a chance to see our band.

And for me, playing live with this band was always my favorite experience. Everything else for me was framed around getting to experience it on stage, whether it be writing a song, recording it, putting out a record, you know going out. It was all set up to have that experience and to have that release. That was what felt transcendent about the whole thing. And so, yeah, I take that part of it pretty seriously, and take my preparation for it seriously.

WHITNEY: I personally feel really engaged and I'm really looking forward to it. Because we're so much better as performers than we were. When you're in your twenties, you're performing with all the emotional baggage that you carry around with you every single day. And for me as I get older, I feel like every year I just stop giving a shit about one thing that bothered the crap out of me my entire life. It’s like a weight that’s gone now.

I feel more creatively free than I did then. I feel like I have a better understanding of what our band is and what our band isn't and I personally feel like I am better equipped to deliver the kind of performance that is quintessentially what the Blood Brothers was about without trying to tack on a bunch of bullshit. This is probably unique to me, but I was always in the headspace that I wanted us to be the biggest band in the world. And that would require a lot of tradeoffs that — I think with good reason — a lot of people in the band weren’t comfortable with.

You’re playing larger venues on this tour than you did during your initial run. You used to play very small, very DIY-type spaces — for example, the Fireside Bowl in Chicago, where I used to see you. Is it easier or harder to connect with your audience in a larger room?

BLILIE: It's not harder. It's easier just because of the makeup of the room. If it's a bit of a bigger venue, then the ceilings are higher and you can breathe. If it's something like the Fireside — that was a pretty extreme venue to play, just in terms of how physically demanding it could get. I remember places like the Fireside, or like the Church in Philly, there'd be so much condensation on the walls that, you know, the duct tape we’d have holding up the merch would just be sliding off of the wall from all the condensation. Theater-size places do feel like a little more of a sweet spot where you're not sacrificing too much of the intimacy. You're not talking about an arena where people are filing in while they're eating a hot dog or something. You're still very close to people, and you're still having that experience.

Working With Ross Robinson On ...Burn, Piano Island, Burn

You guys were, admittedly, this weird, screamo-adjacent band who put out records on Three One G and somehow ended up on major labels in the early '00s. What was it like being that band in the major-label system — I assume there were not a lot of other bands like you in that world?

BLILIE: That would be correct. The subculture that we came from was very small. And there was a clear line of demarcation between the underground — which was artistically vital, relevant, uncompromised, and pure — and the corporate world — which was stale, lame, compromised. You didn’t really see bands cross over into the major-label world, and the bands that did sort of did so at their own peril. It would invite a lot of scrutiny. You know, a lot of times it would sort of spell the end of their band.

WHITNEY: It just seems incomprehensible in hindsight, a record company spending millions of dollars making something like ...Burn, Piano Island, Burn. We went from like being like this, really unknown — kind of borderline despised in some corners — band to, you know, having Ross Robinson pick our CD out of a fucking bag of a thousand CDs. It was like a one in a million thing right?

Wait…is that a real thing that happened? Ross Robinson picking your CD out of a bag? I’ve never heard that story before.

WHITNEY: Yeah. So there was this guy, his name is Casey Chaos. He was the frontman of this band called Amen. They were a late '90s, early '00s Ross Robinson-adjacent band. Casey would regularly just give Ross CDs — you know, lots and lots of CDs for him to check out. And what I was told was that he picked our CD out of a bag — it was This Adultery Is Ripe — and listened to it, and he loved "Rescue". Just from that he had his manager reach out to us.

This was like 2000 — definitely before 9/11 — and we had a band Hotmail account at the time. And we started getting these emails from this guy from a company called Freeze Management. And we had no idea who that was. We kind of blew off the first couple of emails. And then finally, someone put together that this was the guy who recorded At The Drive-In, and we were like, "Hmmmm"....and so it just kind of happened.

At the time it wasn’t our preferred vibe or kind of music. In hindsight — I mean, I fucking love Slipknot and a lot of the stuff he did now — but I think I was a little too stuck up at the time to really appreciate what he was doing. And the experience of working with him was fucking phenomenal. I mean, it was like one of the most amazing things I've ever done in my life.

They tried to sign us to Virgin — that didn’t work out. We tried a few other things. Then we found this company called Artist Direct. That was like a dot-com-era record company — they were kind of the first company to ever put whole catalogs of music on the Internet. And they had Badly Drawn Boy, the Cure, a couple other things. And we got to fly down to Venice Beach for three fucking months and record with this amazing, inspiring dude who loved us and and had this pure admiration for what we were doing. I couldn't have imagined anything better at the time that could have happened to us.

BLILIE: Ross Robinson had found us, believed in us, and was very adamant on making a record with us, and it eventually led to a relationship of trust with him. He had so much cachet and capital in the industry at that time that if he was co-signing on something, then people knew it was to be left alone. And that was our experience, you know, [Artist Direct] left us to our own devices. It ultimately didn’t work out because the label went under. But I will say, to their credit, what we handed them is what they put out. Going into Crimes was a little bit precarious because we were between labels and we needed to find a label that would satisfy that business side of it — it was a little bit of a mess for a bit trying to find another label who would take on that contract. But we did it, V2 were great, we did Crimes with them, and then they folded after our next record. [Laughs] It felt like signing us was always a harbinger.

WHITNEY: The strength of [Piano island] and how fucking insane it is and yet coherent at the same time — you can fully pin that on Ross’ faith in us. Crimes, Young Machetes, everything after, I guarantee it would have never happened without him. We would have put out maybe one more record after March On Electric Children, and it would have been some of the songs that ended up on Burn. Without someone who was like, "I love this band, I want to make sure they don’t have to work and they can just focus on music" — no chance. I give him so much credit for being a really amazing dude.

Ross Robinson is infamous for having these intense, unorthodox methods of working in the studio. Is that what your experience with him was like?

WHITNEY: I didn’t find it that intense. I came to learn, many years later, that for whatever reason, he was very intimidated by us. I think because we were such stuck-up pricks at the time. We came from a very gatekeepy part of punk rock…I love At The Drive-In now, right? I think at the time, At The Drive-In was like, a little too mainstream for me. We were 19-year-olds who gave off a really standoffish vibe, and maybe he picked up on that a little bit, I don’t know. I’ve also heard that he’s harder on non-singers. He definitely pushed Mark, the drummer, super, super hard. But it wasn’t emotionally intense. I mean, we were on the beach all the time. It was just great.

The one thing he did that was sort of idiosyncratic was that he had picked up on something that Jordan liked…we were all really into the movie American Movie at that time. It's a documentary about this guy in Wisconsin that's trying to make a horror movie and, I don't know, It's just really funny. He had it on repeat the entire time we were recording — it was just on a TV somewhere. But other than that, nothing comes to mind in terms of crazy antics.

Do you wish you had gotten to work with him more?

WHITNEY: In a perfect world, if I could go back, I would have John [Goodmanson] and Ross [Robinson] do both of our other records. I think turning our back on Ross is probably the thing I regret the most. Considering what an incredibly talented fucking dude he is and the fact that he changed all our lives irreversibly — the fact that we kind of turned our back on him feels very shitty in hindsight. I wish we had not done that. I wish we could have combined his brain and John’s brain and later, Guy’s [Guy Picciotto of Fugazi, who co-produced Young Machetes] brain.

Recording And Promoting Crimes

When you set out to make Crimes, what were things like creatively in the band? What expectations did you put on yourselves?

BLILIE: I think the best way to answer that would be to look at the record that preceded it. So ...Burn, Piano Island, Burn came out in 2003 — I think the bulk of it was written and recorded in 2002. And for me, I think there's a lot of exciting elements and a lot of really great moments on that record. But it's also a very relentless listen. You know, when you watch a little kid order ice cream and they've got like, rocky road, they've got cotton candy blast, they've got chocolate peanut butter, and then on top of it, it's like nerds and gummy bears and hot fudge. All of those elements are great. But you take like four bites of that thing and you’ve got to go lie down.

That's kind of what that record felt like. We pushed to a certain extreme, I think, as far as we could go. And the only path forward that we saw that was exciting was stripping things down — you know, taking things down to the studs and then going from there. And so Crimes was very much just kind of stripping a lot of the songwriting back. You know, where on Burn, a song might have six parts, on Crimes, it's very traditional, you know: verse, chorus, bridge, chorus, out.

I don't remember how much of that was articulated between the five of us, or how much real intentionality was behind that decision. But I know that when we got into the room and started that first batch of songs, it just felt really exciting and freeing. The songs were coming much quicker and it felt like we were getting into a lane that felt pretty new and vibrant for us. I just remember, after practice I'd be talking with my wife (then girlfriend) and I'd be like, we got two songs done today and started a third. It was just going really quick.

When I look back on the work that we did together, the songs that are always my favorites are the ones that came together in like five minutes. That would be a song like "Trash Flavored Trash." Maybe I went to have a smoke break or something like that. And I came back and Cody and Mark had essentially the framework of that song all worked out. It was those moments where everyone's chemistry was really sort of firing. It didn't feel labored. It didn't feel like there needed to be a whole lot of discussion or hand-wringing about parts and how we were going to make certain parts work. Is it just kind of flowed.

WHITNEY: It kind of just came naturally. I wouldn't say it was a response like, we don't want to do something like this. It was more like, okay, now we've achieved this modicum of success. Let's just push it in a bit of a different direction. Let's just try to loosen this up a little more and let's try to see if we can find a balance between what this band is supposed to be in the eyes of everybody and what we're interested in, right? Every record is just pushing a little bit more out of the confines of being a screamy hardcore band.

What were some of your influences going into the studio? I remember interviewing Johnny for my college paper on the Piano Island tour and he said something like "We don’t listen to any punk music, we only listen to T. Rex and Bowie in the van."

BLILIE: He's right. I remember there was a lot of Bowie. There was a ton of T. Rex. You know, we weren't listening to a lot of contemporary hardcore. The challenge then became, how do we incorporate the music that we're really listening to and that is really exciting us into this template. And what you hear — I guess that’s the result.

WHITNEY: Yeah, I mean, I think that’s pretty accurate. I was also obsessed with Bob Dylan the entire time I was in the Blood Brothers. I always had this horseshit dream of being a folk singer for some reason, and so I listened to Woody Guthrie and Leadbelly and a lot of old folk music. I think it’s kind of natural when you’re doing something that’s in a genre, you tend to listen to things that are outside of it.

BLILIE: You also have to take into account that we were like 22 at the time, and when you're 22, you're probably at your most reactionary. If you feel that you're being put in a place that you don't connect with, your instinct is to just go in the opposite direction. With Burn, we were really proud of that record, but we would be playing these festivals and we would always sort of feel like — I want to be careful, this is not to say that we were like complete elitists or anything like that. But, you know, when you're playing a festival and every band is getting up and saying like, "I want to see a fucking pit"...you kind of retreat and go in the opposite direction.

I do want to be a little bit careful. I feel like I'm giving you an impression that I absolutely hate hardcore. You know, hardcore is a genre that invites a certain amount of macho male posturing. It’s that element of hardcore that I never connected with, because — well, look at me, I just can’t connect to that. But I will say, without fail, the most brutal music that I heard at the time was being made by weirdo introverts. You know, something like Black Dice. It’s not like these are physically imposing people but they start playing and it’s the most brutal thing you’ve ever heard. Or like, the Locust, for example. I just like that subversion of expectations.

To that end, you did Piano Island with Ross Robinson, who is often called "the godfather of nü-metal". Why did you decide to do Crimes with John Goodmanson — a producer I associate more with arty bands like Unwound or Blonde Redhead?

BLILIE: For those reasons specifically, that he worked with Unwound. Repetition was a huge record for me and, I feel like, for a lot of the guys in the band. There were a couple of Sleater-Kinney records that he did that I know that Morgan specifically really loved. There was a Gossip record that he did too. We were just huge fans of his work, and we were trying to figure out how do we create space with all of the disparate elements that are going on in our band? He was in Seattle and we didn't want to travel again and be away from home for two months. And so he felt like a really great choice for the batch of songs that we had for Crimes and what would be appropriate for that music.

The lyrics on Crimes took things to an even darker, more surreal place than on Piano Island. Where did the inspiration for the lyrics come from?

BLILIE: So this was post-9/11. It was the "War on Terror," and there was this banging of the war drum — this sort of war hysteria. The two things that come to my mind are the Toby Keith song and "Mission Accomplished" — these sort of outward displays of American strength. And this nefarious, faithless, ever-present enemy called "terror." At the same time, it felt like nothing that the Bush administration was trying to sell us was standing up to even the lightest amount of scrutiny. So questions like, "Why are we in Iraq?" or "What does Saddam Hussein have to do with 9/11?" would just go unanswered. You got the feeling that something very sinister was going on. And then you would see these images of prisoners — the conversation about "enhanced interrogation techniques" — it was like the worst impulses of humanity were on full display.

Concurrently, you had the beginnings of this hyper-fixation on celebrity culture and the notion of the celebrity as an end unto itself, where it was no longer couched in any particular achievement. It’s this idea of American exceptionalism just sort of mutated and twisted to its ugliest form. I think that’s what Johnny and I were trying to engage with.

WHITNEY: When we first started doing Blood Brothers, I was really inspired by the dude from the VSS — his lyrics were really surreal but also very minimal. There were also some poets I was really inspired by, like Ted Hughes. But by the time we got to Crimes, I wasn’t really reading poetry anymore. I would set aside an hour every day and write in an open writing kind of way, just trying to think of images, ideas or interesting word structures, almost like free association. And so, when the time would come to actually put a song together, all of that writing I would do everyday I would use as reference, just as a jumping off point to make a song out of. With the way that we composed lyrics, we definitely tried to push with every single record and do something that was weirder and less about one thing and more kind of about everything.

Crimes has some really incredible vocal performances. Is that an area where you intentionally decided to raise the bar on yourselves?

WHITNEY: Yeah, it was definitely intentional. Between Burn and Crimes I started taking vocal lessons and became very fixated on increasing my range and was running scales all the fucking time. I think at the time I was probably kind of blown away by the first couple Mars Volta records and was inspired a little bit by the course [Cedric Bixler-Zavala] took from At The Drive-In to the Mars Volta. I think it’s also natural for any band that has two lead singers to try to put space between the two different performances. I think Crimes was the first time we became a lot more distinct about our way of representing what we wanted to do and how we wanted it to work together.

Johnny, you did all the album art for Crimes, correct? What made you want to take that on?

WHITNEY: You know, I’ve always been a really big fan of album art. I think the first time I really fell in love with CD booklet art — for lack of a better term — was Sunny Day Real Estate’s Diary. Just the way that every song has a corresponding image. And it’s laid out like a poetry book, almost.

The only album I did the artwork for was Crimes. We had a designer do …Burn, Piano Island, Burn, but me and Cody were in the room the entire time giving him ideas. And after that experience, I just sort of taught myself how to do graphic design. I took it upon myself to do the artwork for Crimes — I spent time on it obsessively, labored over it for months and months. And it was something to do. There’s a lot of time to kill when you’re a singer and you don’t have to set stuff up every day when you’re on tour.

So you’d just be on your laptop, designing artwork while you were on tour?

WHITNEY: Yeah, just Photoshop in the van. I kind of wished that I didn’t because I really missed out on a lot of fun that other people were having because I was just…working. But it is what it is.

That Infamous Jimmy Kimmel Performance

So…how does a band like the Blood Brothers end up on Jimmy Kimmel Live? What was that experience like?

BLILIE: I think it was just a result of having a very good publicist. Our publicist at the time was this guy Steve Martin. His company was Nasty Little Man — he was the Beastie Boys’ publicist. I can’t think of any other reason why someone would have us on television. Certainly our peers weren’t going on late-night television.

It was a very bizarre, very surreal experience. I will say that Jimmy Kimmel was very nice. He was like, "You know, our announcer is a big fan of you guys, he's really excited that you're here." I remember during the sound check, the producers were really concerned we were gonna break stuff. They kept pointing to the lights that would be in front of us or the equipment and being like, "You know, we’d really appreciate it if you guys would be careful with this." They were very kind about it, but I just remember thinking, they’re preparing for us to just completely destroy their set or something.

WHITNEY: Somebody fucked up and and told them that we were gonna be playing ["Love Rhymes With Hideous Car Wreck"]. And when we did our sound check, the Jimmy Kimmel people were like, "What the fuck is this? We wanted you to play 'Trash Flavored Trash,’" which is totally different. They asked us, "Can you please play this other song because it’s more TV-friendly?" And we were like no, we’re not gonna do that. I think at the time, I kind of wanted to [play "Love Rhymes"] because I was like, maybe we do want to be on TV? But you know, for great reasons, the rest of the band was like no, we’re not doing what you tell us to do. And you know, the response was, "Okay, don’t expect to come back."

The Genesis And Breakup Of The Band

How did the band first start, and why did it take off?

WHITNEY: The Blood Brothers was nobody’s first band. We were in high school, and we were all in bands that we were took very fucking seriously. We kind of started the Blood Brothers almost as like, a way to do something fun where we weren't really like overthinking everything we did. And so, our first sets, the songs were like a minute and a half long. It was just supposed to be fun and chaotic. The Blood Brothers slowly became much more popular than any of the other bands we took a lot more seriously.

BLILIE: You know, at the end of the day, the instrumentation is essentially a three-piece. There's one guitar player, bass and drums, and maybe on a quarter or a third of the songs, there’s keyboard on top of that. My favorite part of our band, to be honest, is the bass and drums. If I listen to the two of them playing in isolation, I don't feel like I'm listening to a hardcore record or a punk record. I feel like I'm listening to something completely different. And I think that's part of what made our band very unique and special. The bass and the drums were the engine. They were the drivers, and it allowed Cody to do so much interesting stuff on top of it.

WHITNEY: Cody's such a fucking phenomenal guitar player. And Morgan is like — I cannot fucking believe that I got to play with somebody that is this talented. His ability to just approach a song and not really know what he's doing and just pull out something that's loose but defined — it's just magic, right? Being around those two guys as songwriters was so intimidating.

Where did the idea to have two singers come from?

WHITNEY: The idea to do a band with two singers, we just straight up ripped it off from this band called Area 51. They were a band in Seattle fronted by Spencer Moody, who ended up being the singer in the Murder City Devils, and Andrea Zollo, who ended up being the singer of Pretty Girls Make Graves. They were in this amazing band where they were both the singers.

I always assumed it was the Fugazi influence.

WHITNEY: Maybe subconsciously that was part of it. But I never thought of Fugazi as a band with two singers. I thought of them as a band with two multi-instrumentalists who just happened to sing.

Like the Beatles, almost?

WHITNEY: Yeah, that’s what their vibe is.

So the Blood Brothers started out as a way to blow off steam in high school and ultimately became something that probably exceeded anyone’s expectations in terms of success. What led to the decision to pull the plug after 10 years?

WHITNEY: We were just really shitty communicators, and we all harbored things that we resented about each other and didn't really air them out. Part of that is a kind of defense mechanism that everybody rightly has when you tour under the conditions that we did, which was being in a van nine months out of the year, doing 12-hour drive days regularly, several times a week. Spending so much time with anybody…sometimes you have to keep things in or else it just doesn't work.

It’s just an insane thing to try to be a musician. You’re pursuing a passion that only 1% of the time doesn’t result in having to accept a really low standard of living. And the older that we all got, when we got closer to our mid-twenties, I was like, are we all-in on this? Or, like, am I gonna be a fucking bartender when I’m 30? So the tension was, do we want to take this somewhere? The exact thing that we broke up about was that we got offered to do Warped Tour and I wanted to do it, Cody wanted to do it, and at least Jordan and Morgan didn’t. But the fight wasn’t about that, really. One of us was just like, why don’t we break up? And that was kind of it. Looking back on it, I wish we would have just taken a break.

Writing Young Machetes was the best distillation of all the different things that we wanted to do. But the process of making it was so emotionally draining. Because at that point, we had a lot of creative differences and it was just really hard to write it. After coming out of that, personally, I just wanted to try something else. I think if we had had a smarter person in the room with us with just a little bit more wisdom, we probably could have seen the conflict for what it was, which was, you guys just need a break from each other. If we had just taken six months off, I think we would have been able to come back to it and make something amazing.

I went on to start another band with Cody that didn’t really do anything, and we put out two records. There was something really magic about the five of us coming together, and it was apparent from the moment Morgan joined the band. Something you can’t plan — it just had to happen. If I was wiser at the time I would know that you can’t just recreate that. You have to suffer through those kinds of conflicts to have this combination of five people who are really, really talented and really, really inspired but maybe not always in the same direction.

TOUR DATES:

11/02 – San Francisco, CA @ The Regency Ballroom

11/03 – San Francisco CA @ The Regency Ballroom

11/05 – Pomona, CA @ The Glass House

11/06 – Santa Ana, Ca @ The Observatory

11/07 – Los Angeles, CA @ The Belasco

11/08 – Los Angeles, CA @ The Belasco

11/10 – Denver, CO @ The Summit

11/12 – Portland, OR @ Revolution Hall

11/14 – Seattle, WA @ The Showbox

11/15 – Seattle, WA @ The Showbox

12/06 – Austin, TX @ The Mohawk

12/07 – Austin, TX @ The Mohawk

12/09 – Boston, MA @ Paradise Rock Club

12/11 – Philadelphia, PA @ Union Transfer

12/13 – New York, NYC @ Irving Plaza

12/14 – New York, NYC @ Irving Plaza

12/15 – Brooklyn, NY @ Warsaw

12/16 – Brooklyn, NY @ Warsaw

12/20 – Chicago, IL @ Thalia Hall

12/21 – Chicago, IL @ Thalia Hall

12/22 – Chicago, IL @ Thalia Hall

The Crimes reissue is out 10/4 on Epitaph.