Porridge Radio's fourth album, Clouds In The Sky They Will Always Be There For Me, came from a backdrop of burnout and heartbreak. The London-based band finished up heavy touring on their last album, 2022's Waterslide, Diving Board, Ladder To The Sky, and frontwoman Dana Margolin was left to confront a painful breakup and a deep exhaustion that came from the vulnerability of constant performance. Margolin began writing these many of these songs as poems, the idea being to remove the places to hide that are built into pop songwriting tropes, making vulnerability and intensity impossible to avoid.

The resulting album is fairly astonishing — it's unmistakably more intense and more widescreen than any of Porridge Radio's prior releases, bigger in emotional and musical scope yet also weirder and more intimate. In our interview, Margolin and bassist Dan Hutchins credit their time in the studio with Dom Monks, who's worked regularly with Big Thief and Laura Marling, as being integral to bringing that out of them.

"I think I was a bit of a mess for a lot of the tracking. I was really struggling a lot, because of how immediate and intense it was," Margolin says. "And there was a real sense in the room that I was just allowed to feel whatever I was feeling and it was fine, and if I was crying or whatever it was, it was just like, okay, yeah, you can just do that, you don't have to be or do anything else. Which really helped get through that process, because it meant that I could give everything to these songs and not worry about collapsing to the ground occasionally."

"[Monks] really allowed us to just exist, and to capture that emotional immediacy in that moment, and he has such a strong philosophy on it. That was really inspiring; I felt incredibly inspired by him. I think all of us came out of that session having learned so much about ourselves as musicians and having gained so much confidence," she adds. "It felt like a very healing process."

Below, Margolin and Hutchins talk about the process of creating each of the album's songs — featuring talk of Florence & The Machine, Led Zeppelin, Portishead. and more.

1. "Anybody"

DANA MARGOLIN: So it started quite differently to how it ended up. I think it was the first song that we demoed for the record, me and Sam [Yardley, drummer]. I had this weird demo and I came into the room and we just kinda built something up, and it became kind of close to what it was in the end. But I think when we brought it into the room and actually played it together is when it suddenly had this big burst of energy. For me at least it felt like a nod to LCD Soundsystem or the Yeah Yeah Yeahs or something like that.

DAN HUTCHINS: Yeah, I remember this was one of the first ones that we went over when we were preparing to record the record. And it was full of excitement. And it just felt like a natural opener for a record as well, because it has a kind of heraldic feel to it. It feels like it's announcing the record.

MARGOLIN: I remember I was imagining it being really happy and bouncy. I was imagining this huge choir, I was imagining that we were like Florence & The Machine, and that it was this big, joyful, triumphant song. Which is quite far from what it is, but it was always like a festival song in my mind. I guess when we added that massive instrumental in the middle, it gave it this kind of extra cathartic moment.

HUTCHINS: Yeah. So when we were working on it prior to recording it, we added an instrumental section to the end which is that big explosive moment. And even before that part was in the song it felt like the end of that section was large and explosive. We didn't really realize how much more mileage we could get out of it with adding that instrumental.

MARGOLIN: It's cool as fuck. It's really fun to play. The way that all the different parts weave in and out of each other, I think, is really fun. There's a bit of the song where I just scream. It's just before that instrumental section, and it's like this big release moment. It feels like it builds and builds and then it floods out, in a really satisfying way.

The repeated line in this song, "I don't wanna know anybody" — something that I've picked up across your albums is you write a lot about the word "want". Have you ever noticed that you write about want a lot?

MARGOLIN: I think I write about reaching and yearning and grasping a lot. I think yearning is a massive part of my life. I love yearning. And maybe unconsciously, I'm writing songs about trying and reaching and wanting and grasping and running, and… yeah, [I'm] obsessed with yearning.

2. "A Hole In The Ground"

MARGOLIN: I think this one much more than "Anybody" was a kind of poem song. With "A Hole In The Ground" I felt like I was creating a kind of story or a fairytale, or something that was kind of confusing and joined together in a narrative that feels kind of… like you're in some kind of vague dream. And it's quite confusing what's happening until the end, when you look back and you realize what's happened.

Was that deliberately the feel that you wanted for the song or was that what you realized about it after you'd written it?

MARGOLIN: I think it's what I realized after I'd written it, and also after we'd put it together as a band. I never really know what I'm doing until after I've done it. There's always these strong ideas of what the songs should feel like, but it's only with hindsight that I tend to look back and go, "Oh, that's about this, or that's what I was trying to do there." I feel like there's something quite confusing when I'm within the process where you're kind of feeling out where the walls are but you don't know exactly what they look like. And I think maybe this one was like that. There was this weird push and pull with "Hole In The Ground" of how soft it should be. I remember asking you guys, Dan, if it felt like it needed to be really hard or really soft, and a lot of the song was about finding the balance between the hard and the soft. It's delicate, it felt like anything could tip it too far one way.

That's interesting about the hard and soft balance, ‘cause I feel like this album definitely goes to those extremes. When you guys are in the studio and writing songs together, do you ever go too far one way and go, hm, I'm not sure if that's something we can do, or is it kind of anything goes?

MARGOLIN: That's definitely happened before. I feel like there's times where we'd be playing a song and just jamming it out for a while and figuring out where it's going, and then stepping back and going actually, I think it needs a slightly different feel to it. Did any of those songs end up on the album, though, is the question?

HUTCHINS: Yeah, I'm not sure, I can't remember. But it's like you've said before, Dana, every song has an essence, and it can find expression in different ways. And when it gets brought to the band, that's sort of the fun of being a collaborative musical endeavor, is you can really work these things out. You can experiment with dynamics and all of those things and figure out how best to express the song in that particular way. And it was also like, when we were working with Dom, his whole point was that the versions of the songs that are on the record are not the absolute definitive versions of the song.

MARGOLIN: Yeah, it's definitely opened us up.

HUTCHINS: Yeah, exactly. He just said it's the record of how the band sounds at this particular time in this particular way.

Do you guys consider yourself a live band?

MARGOLIN: Yeah, I think we are a live band really, we always have been. It's always been about a feeling in a room and the relationship between us as performers and the audience and the feeling of the sound and the space. I think that's always been a really big part of it. And I also think what Dom managed to bring out of us was that live feeling into a record. I think the reason this album sounds the way it does is because he pushed us to sound how we sound. Which was really amazing, to be told, no, you can sound how you sound, and we'll get that, and it will be really fucking good.

And then at the end of it, it hit emotionally, very immediately. We listened back and we were like, oh, we do sound how we sound. It can be confusing because I think when you're recording music, it can get really tempting to kind of be a perfectionist about every single part, to quantize the drums and multi-layer things and to redo parts and to push things around. But this was very much like, no, you're recording it live. It's like, the vocal take and the guitar take will be the same, and it will be the one we all played together. And that felt really unique about this process.

HUTCHINS: And I feel like in so many instances, the first takes were the takes, more or less.

3. "Lavender Raspberries"

MARGOLIN: This is one of my favorites, I think. I feel like the essence of "Lavender Raspberries" is something that I've been trying to express in a song for the whole time I've been writing songs, and I feel like I got close to this thing that I've always been trying to describe. It captures a certain experience of dissociation and depression that I think is quite hard to explain to people sometimes. I'm really proud of it, I think it's just the most insane song. I remember when we played it to Dom, he was like, ‘I don't really get it, it seems kind of horrible.' [Laughs]

HUTCHINS: Yeah, the intensity doesn't let up, the song is intense from start to finish. And we love that.

MARGOLIN: It just gets worse and worse. [Laughs]

HUTCHINS: Yeah, and it just mounts to the end. It's unrelenting. And I think it didn't quite make sense to him at first.

MARGOLIN: Yeah, he was like, "Is there gonna be a chorus that comes back," or — he was suggesting changes to the song that kind of made it nicer to listen to. And we were like, no, that's not how the song goes. It just doesn't feel like that. But then as soon as we realized that, it's like, this is a dissociative song. It's supposed to feel like you're on a horse and you're just holding on and the horse is going really fast and you're just trying not to fall off. It's such a weird, dissociative, uncomfortable song, but I think that's what makes it so exciting and so fun to play.

HUTCHINS: And audiences really respond to it. The times we've played it live, you can feel a palpable tension in the room.

MARGOLIN: Yeah. It's a kind of like, "What the fuck did you just do?" song. I remember writing it, and I wrote it in drop D, and I never really change tunings to write songs. But I look at the chords, and I don't really know how I wrote it. It kind of just wrote itself.

There's this cool eerie synth that's going on throughout the first part of the song. How did you go about creating the atmosphere in this song? Was there a sort of trial and error of looking for the right sounds?

MARGOLIN: I just had these chords and I played them to Sam, and Georgie [Stott, keys] came in — and Georgie is like, synth lord, always. She is always playing weird old Yamahas and Casiotones and bringing out these really great tunes. And she kind of heard her keyboard part, and she wrote that keyboard part, and it completely lifted and changed the song, and made it so spooky and weird. The way that it fits in with the timing of what I'm playing, at first it was really confusing, but I think it actually really makes the song. But yeah, that was all Georgie.

HUTCHINS: Yeah, Georgie has an immense capacity just to pull out the most amazing riffs. The other thing I really like about that in terms of the keys is it sounds like a carousel at one point. There's like a carny kind of sound to it which I absolutely love.

The song builds to this heavy, rocking out part. Tell me about doing that part together.

MARGOLIN: I think Sam's drumming really brings that together in a massive way, because they grew up listening to so much nu-metal and kind of dad-rock bands. They go nuts at the end of the song, and it gives it such power and such raw emotion. The amount of emotion that they carry in their drumming I think really comes through on a lot of these songs, "Lavender Raspberries" especially.

4. "God Of Everything Else"

This one I think is my favorite song on the album. It opens in such a heavy place — "Trying to forgive myself for wishing I was someone else." Is that where you started writing the song or did you start somewhere else?

MARGOLIN: I actually wrote the chorus [first]. It was one of the first songs that was written for the album. I remember I was just sitting at home, and I wrote this chorus, and I called Sam up, and I was really struggling at the time. And I often do this with songs, I'll just phone Sam and play them something I've written over the phone before I've finished it or figured out what it is.

And I played them this chorus and I was like, "Ah, it's kind of shit, I don't know what's gonna happen with it, I don't have the energy to record it." And they really liked it, so — it's the first time this has ever happened with any song, but I showed them the chords, and I showed them the chords I wanted to play in the verses, and then they recorded a skeleton for it and sent it back to me, and I just recorded the vocals over it. But at the beginning it was only the chorus. And when Sam had sent me that skeleton, it actually made more sense as a whole, and they also wrote those outro four measures as well. I think that made a really big difference to how the song ended up. Because I had this melody and this vague idea, but I probably wouldn't have ever turned it into something, and they really brought it out.

How do you guys think of this song? It feels like a real moment on the album.

MARGOLIN: I think it's kind of on-the-nose. I think it's really funny just how on-the-nose it is. There's not very much subtlety about it, which was really fun to lean into. And it is just a catchy banger, I think.

It feels like one of the richest musically, arrangement-wise. It's got the violins going on and all that stuff. Tell me about putting together the arrangement for the song.

MARGOLIN: Again, that was Sam as well, coming in with this really strong idea of how the strings should fit in and building it up in that particular way. I think they also wrote maybe like half the keys part of this one. This was one, though, where when we then came into the room, I think we spent a bit more time on the feel of it and kind of pulling it back and allowing it to have a bit of space where we needed it.

HUTCHINS: Yeah, dynamically, I feel like when we started working on this, the arrangements were all very much set, but trying to figure out how to play it as a band, to let it breathe and to give it space, took a little bit of time. Particularly things like the tempo, 'cause it's quite an easy song to speed up, but actually if you keep it slow and give it kind of a sluggish feel, especially in terms of rhythm section, then that's how you service the emotions of the song best.

MARGOLIN: When I first played it to Georgie and Sam, Georgie thought the lyrics were "Don't need to know where you are, you'll be hit by a wave machine." [Laughs] It kind of became that for a little bit.

Dana, you mentioned the outro part of the song. I wanted to ask about your vocals, they get really intense and raw. For you as a vocalist, is that a challenging thing, or a fun thing? How does that feel?

MARGOLIN: I really love singing like that, and really letting it all come out. I think when I have the energy, it's really great to release it. The verses of the song are again quite dissociative, and there's this theme across the album of this fog that I am in, and I have this image from the verses of this song of kind of grasping at walls in the dark, and — again, it's kind of the reaching and yearning and trying to find something, looking for something. And then when it gets to that "sick, sick sickness" end chorus into the final release outro, it just feels really like something can be cathartically let go of. And I find it really enjoyable to sing those parts.

HUTCHINS: I feel like the end part of that song has that strange, uncanny feeling of being both intense and really tender at the same time. Instrumentally, it's very delicately balanced, with everyone playing synchronized parts. But it has that sort of contradictory feeling.

5. "Sleeptalker"

MARGOLIN: This one, I started writing when we got back from tour. It was kind of early 2023. And I was just really burnt out. I had no energy, and I didn't know how I could kind of do anything. But also, I was in a relationship and I was very in love with this person, and it was kind of like getting me through the days. So it was a love song, I guess. It is a love song. And it was a song for feeling really like you have nothing left inside you, but there's this beautiful relationship that's giving you hope, or there's somebody who you look towards for comfort. It balances those two things, of life is hard but actually, look at all this love that I have. The song is, in a way, weirdly divided into two halves. Where you have a really soft, gentle intro that feels quite slow and sad and warm, and then it just gets loud and abrasive and fast, and then it's over.

6. "You Will Come Home"

This one has a twin lyric with "Sleeptalker," where it says "You make it so easy to love you." Are those songs linked to you in your mind?

MARGOLIN: Yeah, they're about the same person, they were written around the same time. They're very much in the same musical world. I really love "You Will Come Home." I remember when we played it to Dom who produced the album - what did he say, that it sounded like a kind of weird English folk song? Like a Wicker Man-esque kind of thing. Again, this is one where I wrote those first two sections and I sent it to Sam. I came round to their house, and they'd just kind of been playing around with what I sent them, and they just added that pop-punk section onto the end. [Laughs] And they just looked at me and they were like, "I don't think you're gonna like this." And I was like, this is insanely good, and what the fuck have you just done? Cause I'd just written this really soft, weird little folk song, and they'd added just a kind of… Blink-182 moment.

HUTCHINS: In a lot of these songs there are these moments of release, and this is another one. By the time you get to that larger, louder section, it feels like all of the emotions have been let loose.

MARGOLIN: Yeah, exactly. It took me a really long time to figure out how to sing that end part. Learning how to breathe and how to get it out when it suddenly just ramps up so intensely, was quite difficult to figure out how to do. And it is also quite a revealing song, I think it's quite exposing. It's quite painful, I think, that song. I remember in the studio, it was around the time we were recording it, it may have been that day — I had to leave twice in the space of four days, once for a wedding and then four days later for a funeral. So I spent quite a lot of time driving to and from Somerset and London in between. It was like 9 o'clock and we'd just finished, and we'd been talking about Led Zeppelin all day, Led Zeppelin IV. Do you remember this day, Dan? There was like a link between, especially "You Will Come Home" and Led Zeppelin.

HUTCHINS: Yeah. It was "Anybody" as well. I think we were talking about both of these songs, but we were talking about the big instrumental parts. We were talking about how listening to [IV], you can hear them straining to keep it together in the first track. And Dom likened, I think it was the instrumental part in "Anybody," to that. Dom would sort of remind us that those were the most characterful parts of the song, is when you could hear us straining to stay together as an ensemble.

MARGOLIN: I think with this one, I remember on my drive home I was listening to "Stairway To Heaven," and I was like, oh, this is "Stairway To Heaven!" This is what we've done! [Laughs] I was like, oh yeah, it combines that kind of dark English folky thing with something that then just explodes into just like a big rock song.

What you were saying, Dan, about feeling that strain to keep it together, I love that in music. When it sounds like it's about to go off the rails at any moment, but that's what's so awesome about it.

MARGOLIN: Yeah, I mean like, with "Anybody" actually, the take that we used was the first take, and my headphones fell off in the middle of the song, and they landed on my guitar and I started laughing. But I kept playing through the song 'til the end, ‘cause we had a rule that it doesn't matter what happens in the take, you keep going to the end. But because of that, there was a section in the middle of the song where you can hear my headphones falling off and I start laughing and I don't sing it the way that I wanted to sing it. I think that was the only song where I then overdubbed another layer of my vocal, but we kept the original in and blended the new one in as well. But it really does feel strained, because I was literally just like holding my guitar like "Fuck!" with my headphones down, while I was laughing and trying to sing and trying to get this thing out. And I think that's part of why that take sounds so exciting.

HUTCHINS: I love that about it. Every time I listen to it and I hear you chuckle, I feel like it really captures what it felt like in the room.

MARGOLIN: And also I guess "You Will Come Home" as well, the take we kept is one where I actually played a really weird chord by mistake in the middle of the end section. And everybody agreed that that was the take we had to use, and I spent quite a long time asking everyone if we really wanted to use the take, or if we wanted to just punch in for that bit. And it was quite unanimous that that moment in the song added just like a sense of us in the room, straining, and the character and the intensity I think was really brought through by that. I think a lot of this album, we learnt a lot about honoring our mistakes, and seeing accidents as actually kind of improvisational moments that added things to the songs. But I think that was only because we'd got so tight and we'd spent so long practicing and arranging and figuring out how we were gonna do it.

I feel like it feels so different to be the person who made the mistake. When everyone else is like, "It's great, let's keep it in," but you're like, "Yeah, but I fucked up."

MARGOLIN: Yeah, I think that you have to let go of needing to be in control of everything. When I wasn't the person who'd made the mistake, I'd hear someone else's mistake and go, "That's amazing," or, "That sounds great, we should keep that in." I remember there was a lot across the whole album where — so we kept all the live vocal takes, Georgie and I would sing together. And what happens when we sing live together is kind of different to what happens if we overdub vocals afterwards. And there were a lot of moments where the way that we sing together wasn't necessarily how we'd planned to sing.

But Georgie's backing vocals are just incredible, the way that she sings and the way that she finds harmonies and matches her voice to mine in a way that feels really natural — we've always sung together, and it's always felt really good. And Georgie would sing something and listen back and go, oh, it's really out of tune, it's not how I wanted to sing, I wanna change how I did it. And Dom would come in and go, no, this is incredible, like, the way that you sing backing vocals is better than anything ever, it's so powerful and it's so raw and it's so characterful. Whoever was making what they thought was a mistake, everyone else would come in and give it another ear and be like, nah, you're wrong.

HUTCHINS: I feel like at many points throughout the record I would have crept over to Dom while he was mixing and be like, do you reckon maybe I should lay down another version of this bass cause I'm not quite sure, and he would be like, no, this is the spirit of the song right here. You don't need to worry about these sorts of things.

MARGOLIN: Yeah, and I feel like the way you played on it, Dan, as well, it adds so much, and I just feel like the way that you carry the feel of a song through the way you play bass is so — it's amazing to play music together, it's so fun.

HUTCHINS: Thanks, mate.

7. "Wednesday"

HUTCHINS: Well, I've got one thing to say about "Wednesday," which is that every time I hear the big instrumental parts I see — this is crazy, but I see sort of black and white archive footage of people moving around a ballroom. I have no idea why. For some reason, it just sounds like a waltz. I see people waltzing. It has that sort of ethereal, dreamy kind of feel to it.

MARGOLIN: I think it was quite a unique song in that when I wrote it, it was just on acoustic guitar, just with one note per line. It's so simple. I guess it's a real poem song in that sense. It started off with such a kind of simple beginning. And even the instrumental section, I feel it has so much space in it. Which is quite different from I think a lot of the kind of things I will write. I really loved though when we came together as a band, and just allowing those instrumental sections to explode out of themselves. It feels really good to play.

HUTCHINS: This is a big thing about this project's DNA, which is the songs quite often start as poems. I feel like that was a big part of creating a collaborative relationship with Dom, was showing him that that's how these songs are structured, that's how these songs work, is they start as poems and then become songs.

Do you think that that gave Dom a different approach to producing the songs?

HUTCHINS: Yeah, I think it took a while for him to understand the structures of some of the songs and how they worked, because they started life as poems. I mean, what do you think, Dana?

MARGOLIN: Yeah, I don't think it necessarily took a while. It took showing how they should go and that they didn't need repeated choruses or they didn't need — it was like, we needed to set out what the songs looked and felt like. I guess it is quite a weirdly structured song, this one, as well. It's not a classic kind of pop song structure. Which is the same for a lot of them. It started out as almost like a meditation on a feeling or a thought, and then it turned into a more expansive song.

8. "In A Dream"

This song uses a typewriter as percussion. It has this weird, uncomfortable, almost like wet, splattery sound in the song. How did that come into fruition? Was there a conversation of like, is there something weird that we can use as percussion for this song?

MARGOLIN: So this was a really early one. I'd written something really basic and I sent it to Sam and they'd made this demo for it where they'd sampled in their bedroom a tape recorder, just pressing down the buttons on a four-track, to make the percussive noises. Then as we started to arrange it as a band, it grew out of this very early demo that was really — it was actually really, really beautiful what they'd made. It had all these different really amazing parts, and we got into the studio and we kind of wanted to recreate that sound of the tape machine being sampled. And in the studio was an old typewriter, so we sampled that instead. I actually have the sheet of paper which Sam was typing on with that typewriter. [Laughs] It is spooky, this is a spooky one.

I feel like that goes back to what we were talking about with "Lavender Raspberries," the kind of eerieness that you guys create in these songs. In this one as well, the melodies and arrangements definitely give it that eerie, spooky feeling. Tell me about coming up with those.

MARGOLIN: Yeah, so I'd sent the early demo to Sam who'd kind of come up with this arrangement. And then when we all came together, it was much more about teasing out all those different parts and figuring out how to make it grow in a live way on its own. I really love the bass in this, there's some really amazing fills that Dan plays that are just so satisfying. I think to me it always felt kind of Portishead-y. When I wrote it, I thought I was writing quite an uplifting, happy song. I was like, this is a love song. And it turns out it was actually just a very sad, heartbreaking song. It turned out much more dark and brooding and upsetting.

Since this song has the lyric, "In a dream I am painting," I wanted to ask this — I know, Dana, you are a painter. When you're painting, does that feel like a completely different expression than the things you express in Porridge Radio, or does it feel like part of the same thing for you?

MARGOLIN: If you think about a creative practice as a whole, I'm one person and I have all these different places where I can express different creative urges in different ways and different places. They are separate, but they are also tied together. And with a lot of these songs, I made lyric paintings as I was writing the words, and as those words became turned from phrases or poems into songs I painted a lot of them. They exist for the whole album, there's just different paintings for most songs. And so they help me make sense of those phrases and take them out of context and think about them in new ways — like, words can mean different things in different contexts, and I think it's the same with the paintings. They allowed me to look at the songs from a slightly different angle, to focus in on one particular part of it. But I really like having lots of different mediums to work with, because when one doesn't flow another one does, usually. Which means that you never really get stuck in a block, you just turn to something else.

9. "I Get Lost"

MARGOLIN: "I Get Lost," I actually wrote in the studio the day before we recorded it. Sam and Dan had gone home, it was pretty late at night, and me and Georgie were just left in the studio. I can't remember what we were doing, but we finished recording all the other songs, we were maybe adding a bit of extra synths or something. And I was playing this song that I'd written the day before in the place that we were staying, this house that we were renting for a few weeks, and I sat downstairs in the morning and just started writing this song. And Dom just suggested that we record it. So we just kind of sat in the same room together, Georgie on an organ and me playing acoustic guitar, and yeah, just recorded it. And then the next day Sam and Dan came in and were like, oh, it would have been fun if we'd made a full band version of that. But it was really nice to dial everything back and have something that was just acoustic guitar and an organ, and really just — yeah, I really love how it's simple and it's soft. It felt really amazing to record this album, it was really fun to do, and it felt like a very healing process. And I feel like this song was a very healing song. It was about the process itself.

10. "Pieces Of Heaven"

To me this feels like a turning point, like the darkness of the album coalesces here before "Sick Of The Blues," which is a significantly lighter song. Were you thinking about that, it having a place in the narrative of the album or the emotional journey of it?

MARGOLIN: Yeah, definitely, it was placed there on purpose. Dan, do you remember what happened?

HUTCHINS: I think this one in terms of the songs that were up for inclusion got included somewhat late in the day. We started working on it while we were rehearsing for the recording. And everyone agreed that it should have been on the record. It was a very organic process putting that song together as a band. Dana brought the song and we all kind of built our parts to it. So yeah, maybe that speaks to the narrative structure of the album because of the point at which it turned up and was included.

MARGOLIN: It felt really fresh to have a song that felt so much softer, and it is soft the whole way through. And at the end, Dan, Sam and Georgie are all singing backing vocals, and I love that I just kind of drift away and they all come in and they're all weaving in and out of each other. I think it's really beautiful. And yeah, it was a really late song to be written for the album, and it felt very healing to me. It felt like a finally knowing myself kind of song, which was really nice.

HUTCHINS: It's the sort of song that sounds like it could go on forever. The way that it just sort of loops around, it's like, we happened to just record that song for the particular length of time that it is, but it sounds like it could have just gone on into the ether. And again, yeah, Georgie's backing vocals on that track, you can hear the strain.

MARGOLIN: Yeah, like she slowly falls apart. And I think she wanted to redo it, and we were all just like, no, it's the most beautifully heartbreaking vocal take. It's really powerful.

There's a motif of birds across the album. The swallow on "You Will Come Home" and the sparrow in this one. There's also a swallow on the cover of the album. So tell me about that, is that deliberate? Is that just imagery that you like or was there more to that?

MARGOLIN: I found that I needed a symbol to describe a particular relationship that was happening, and I needed to find a way to kind of symbolize it. So yeah, I think the swallow was what came in as the symbol for a person who comes back and goes away, because a swallow is a migratory bird. And then at the end of this song where the swallow becomes a sparrow, it was kind of questioning whether or not I really knew what that thing was. It was like the swallow changes into a sparrow — but it doesn't change, it's that I suddenly notice that it was something else.

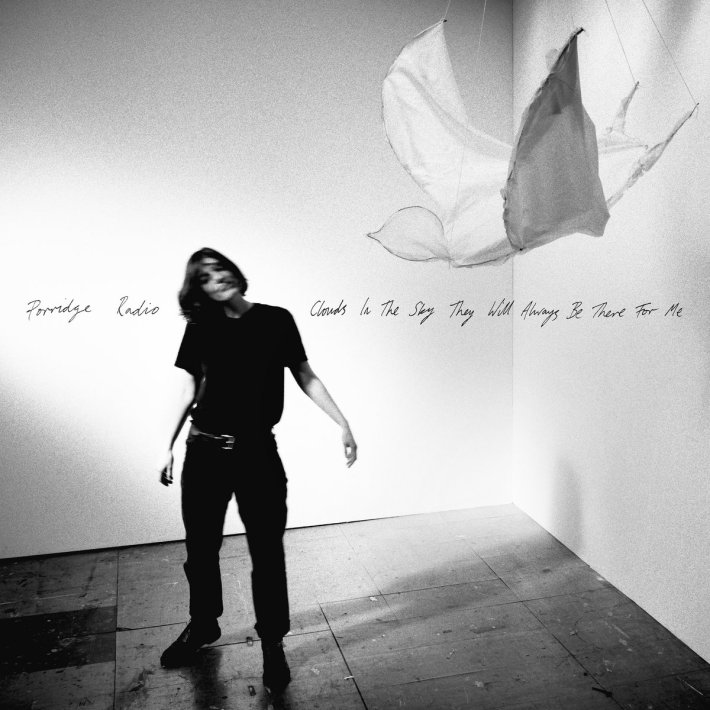

The swallow on the album cover, is that a painting or a physical sculpture?

MARGOLIN: It's a sculpture, it's a mobile that I made out of wire and fabric. I started making it kind of mid-last year, as I was writing a lot of these songs. And it was only really whilst we were recording the album that we realized the album cover shouldn't be one of the paintings I'd been doing, but it should actually be a photograph, and I then realized I needed to finish this sculpture and it needed to be a photograph, and that I should be in it. So then we found Steve who took the photo — he did the whole album cover shoot, and he also did the press photos, and he managed to kind of bring this idea that I had of myself interacting with the swallow to life.

11. "Sick Of The Blues"

This obviously closes the album on a much lighter note.

MARGOLIN: I didn't really like this song when I wrote it. I just thought it was kind of like some stupid thing. I was going through a big heartbreak, and I sat down and wrote this song as just something to get out of my system. And I showed it to the band and everyone said it was really fun and we should just jam it out and have fun with it. So I think we just did, and we just allowed it to grow and be loud and be this kind of weird, dissonant but exciting, fun, stupid thing.

There's that cool moment with the trumpet at the end. Was there a feeling of like, we need some really fun, triumphant horns at the end of this?

HUTCHINS: How did you describe this section, Dana? Everyone's soloing at the same time? That's pretty much what's happening.

MARGOLIN: Yeah, everyone soloing together. It's true, ‘cause originally that part just came out of us jamming it and having a laugh, and we kind of got to the end of the song — it kind of just happened by magic accident that we wrote it like that. I don't really remember what happened.

But yeah, we all were playing our own solos on top of each other and we just thought it was really funny. And then we got into the studio and our friend Freddy [Wordsworth] came in, he plays trumpet across different songs on the record, and he's just got such a soulful warmth to his tone. And we just kind of looped that bit and told him to keep soloing on it, and it was just getting more and more ridiculous. It just really kind of rounds the whole album off with this kind of — it's silly, and it's just us all being loud and having fun with something. I feel like there's a kind of hope to it and a kind of joy within it, and I'm really glad that it ends on that note after going through so much emotional turmoil leading up to the end of the album.

It feels like this song is the feel-good rockout moment musically, just the simplicity of it matches that lightness. What does it feel like to play the song as a band, either when you did it in the studio or having done it live? MARGOLIN: It takes a lot of energy, I find. I find it quite hard to do. I don't really like playing it that much, to be honest. I think it's just because of the way that I sing it, it requires a lot of joy and energy, and that's sometimes hard to muster. But in the studio I think by the time we got there it was really fun to do, and it felt good when we were doing it.

HUTCHINS: Musically, playing it as a band, it feels like we're lifting each other up. It has a very optimistic feel to it.

MARGOLIN: Yeah, it really does. It feels like the first bit is building this tension really hard, you're kind of holding onto it, keeping it all together, and then it just kind of lets rip, and that's really fun.

Clouds In The Sky They Will Always Be There For Me is out now on Secretly Canadian.