November 26, 2016

- STAYED AT #1:7 Weeks

In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present. Book Bonus Beat: The Number Ones: Twenty Chart-Topping Hits That Reveal the History of Pop Music.

Silence descends. Time stops. Famous faces freeze into rictus grins. A ghostly camera drifts up the campaign plane's aisle, capturing the petrified bodies of an entire team of people who are about to fail and whose failure will have wide-reaching global consequences. Some of those immobile faces belong to anonymous functionaries, and others are among the most recognizable on the planet -- a former president, a former Number Ones artist. At the center of everything, we see a woman who remains simply incapable of taking part in viral hijinks without coming off as the most condescending human being who has ever existed. This is Hillary Clinton's Mannequin Challenge video. The day that she posts it on her Twitter feed, she will lose the presidential election to Donald Trump.

Whenever you see a video of a long-past viral trend at work, that video functions as an awkward time capsule, a quickly decaying record of a phenomenon that briefly entranced an online world that soon forgot about it. But you might never see a viral video that's aged quite as rapidly as Hillary Clinton's Mannequin Challenge. The timing is absolutely brutal: This lady who's run this unbearably smug and arrogant presidential campaign, about to lose a shock upset to a man who should've never been considered electable, caught in the closing seconds of her doomed run. By the nature of the video, she's literally frozen in time, unmoving, until it's time to unfreeze.

Maybe worst of all: She fucks it up! It's not just the Secret Service guy moving around at the front of the plane. It's also the soundtrack, or the lack thereof. The first Mannequin Challenge video, which went up online a few weeks before the Hillary Clinton one, didn't have a soundtrack, either. But in the early days of the trend, a pattern emerged. If you were going to post a Mannequin Challenge video, that video had to be set to the chiming, hypnotic strains of Rae Sremmurd's "Black Beatles" intro. If your Mannequin Challenge video didn't have "Black Beatles" in it, your Mannequin Challenge video wasn't shit. Everybody knew that, but nobody told Hillary Clinton. Hillary Clinton probably wouldn't have won the presidency if she'd put "Black Beatles" in her video, but in a close election, you can't write off any hypotheticals. Maybe if she did this thing right, we'd be living in a different world today.

Hillary Clinton didn't win. We know this. Shortly after the election, however, "Black Beatles" notched a big victory. The song climbed to the top of the Billboard Hot 100 -- a first for Rae Sremmurd, their guest Gucci Mane, and an entire ascendant generation of Atlanta rap auteurs. "Black Beatles" was a hit before it became inextricably linked with one particular meme, and it remained a hit after the meme faded into the collective memory. But the combined power of the song and the meme was enough to shift pop-chart hierarchies and to inaugurate a different era of the Hot 100. Too bad it wasn't enough to get anyone elected -- not when the candidate in question fucked up the challenge, anyway.

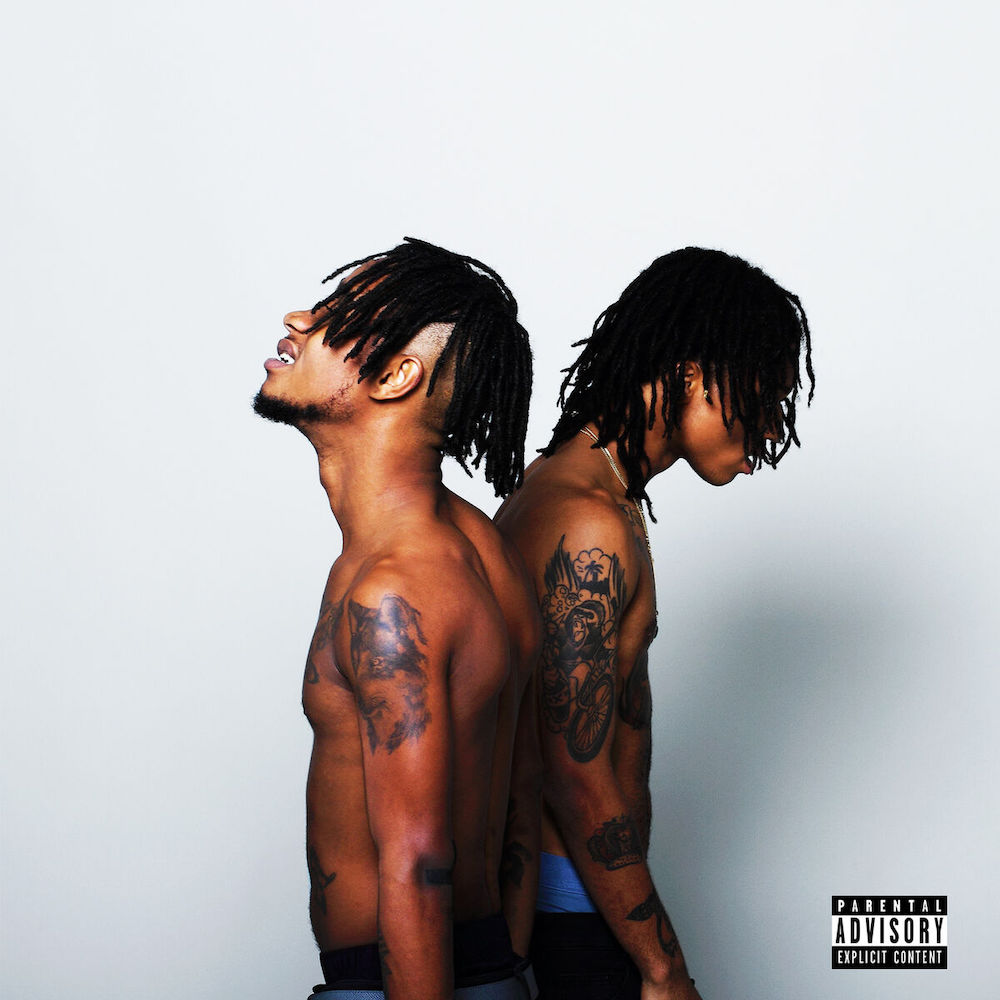

Before "Black Beatles," the two brothers in Rae Sremmurd were cute young guys who had a great run of party-rap room-shakers and whose sneaky melodic sensibility was becoming a behind-the-scenes force in rap and pop. Rae Sremmurd made hits before "Black Beatles." They made more hits than anyone really expected of them. They punched high above their weight class, earning enough critical respect that they drove certain rap gatekeepers batshit insane. But "Black Beatles" was something else -- a song that became a phenomenon, a source of mania.

Brothers Aaquil Iben Shamon Brown and Khalif Malik Ibn Shaman Brown were both born in Inglewood, California. Their single mother served in the Army and worked on tanks, and she was stationed there for a little while. (When Aaquil was born, Michael Jackson's "Black Or White" was the #1 song in America. Khalif is a year and a half younger, and Janet Jackson's "That's The Way Love Goes" was the #1 song when he was born.) The Brown family moved all around the country when the brothers were kids, and they eventually settled in the housing projects of Tupelo, Mississippi.

As teenagers in Tupelo, the Brown brothers started rapping. Aaquil called himself CaliBoy, while Khalif was Kid Krunk. They put together a local group called Dem Outta St8 Boyz, producing their own tracks and clearly following the example of former Number Ones artist Soulja Boy, another Mississippi-based teenager who produced his own records at home and who rode those records to viral fame. The video for Dem Outta St8 Boyz' deeply annoying early song "Party Animal" is just one entry in the thriving genre of lo-res Soulja Boy imitations posted on YouTube in the aftermath of "Crank That (Soulja Boy)."

Dem Outta St8 Boyz mostly rapped about partying -- they still mostly rap about partying -- and they spent all their available time working on their music, sometimes neglecting school for long stretches. Their mother eventually kicked them out, so the brothers squatted in a warehouse and started throwing parties there. They entered local talent competitions, and they made it as far north as New York, where they competed in a televised contest on the BET video-countdown show 106 & Park. That performance didn't land a record deal for Dem Outta St8 Boyz. Through mutual friends, though, the brothers met Pierre "P-Nazty" Slaughter, a producer who worked for Ear Drummers, the production company founded by Atlanta hitmaker Mike Will Made-It.

Mike Will Made-It grew up in a musical family just outside Atlanta, and he started making rap beats when he was 14. A few years later, he sold a few beats to Atlanta cult hero Gucci Mane, and Gucci rapped over those tracks on his 2007 mixtape No Pad, No Pencil. From there, Mike Will helped craft hits for rappers like Meek Mill, Future, 2 Chainz, Juicy J, and Kanye West. As a producer, Mike Will worked in the Atlanta rap tradition, and he leaned into all of its tropes -- stuttering hi-hats, simple keyboard hooks, deep globs of sub-bass. But Mike Will's tracks were slightly melodically sweeter than those of his peers, and he had an easier time crossing over. In 2013, Mike Will landed a song in the top 10 for the first time. "Love Me," a Lil Wayne/Drake/Future track that Mike Will produced, made it as high as #9. (It's an 8.)

The year after "Love Me," Miley Cyrus tapped Mike Will to help her shake her Disney-kid image, and he contributed a bunch of rap-adjacent party songs to Cyrus' smash album Bangerz. "We Can't Stop," a Cyrus track that Mike Will produced, made it to #2. Cyrus also kinda-sorta rapped on "23," a Mike Will track that also featured Wiz Khalifa and Juicy J. That song peaked at #11, and it remains Mike Will's highest-charting single as lead artist. ("We Can't Stop" is a 5. Miley Cyrus has been in this column once, and she will return.)

Mike Will was too busy with big-name collaborators to pay much attention to Dem Outta St8 Boyz, at least at first. The Brown brothers used the Ear Drummers studios to record, and they put out a few more tracks and a 2012 mixtape. But money was slow, and the brothers had to move back to Tupelo and get jobs. Aaquil found a position at a mattress factory, while Khalif flipped burgers. Aaquil rented an apartment, and they started throwing parties and recording music there. After a while, the duo's producer friends convinced them that they needed to return to Atlanta. This time, they caught Mike Will's attention, and he signed them as the first artists on EarDrummers Entertainment, his new Interscope imprint. Dem Outta St8 Boyz changed their name to Rae Sremmurd -- "EarDrummers" spelled backwards -- and both brothers chose new rap names. Aaquil called himself Slim Jxmmi. Khalif first become iHipster Lee, a very funny name, before switching to the more sustainable Swae Lee.

The newly rechristened Rae Sremmurd, a world-historically terrible name, made their debut when their track "We" appeared on a 2013 Mike Will mixtape. They hit the club circuit hard, performing on any stage that would have them. At SXSW in 2014, Rae Sremmurd were all over the place, playing as many shows as possible. (I was at SXSW that year, and I never saw Rae Sremmurd, but I definitely noticed when their name was thrown around.) Shortly thereafter, Rae Sremmurd released their debut single, the dizzy Mike Will-produced earworm "No Flex Zone." That song quickly took off, peaking at #36 on the Hot 100. "No Flex Zone" lives on, soundtracking a WingStop ad that's aired constantly during every sporting event that I've watched in the past year or so.

"No Flex Zone" is a ridiculously catchy song. It's squeaky and spacey and energetic and memorable, and it seems to move fast and slow at the same time. It's not about anything, but the world will never stop needing party-rap anthems like that one. "No Flex Zone" did not, however, sound like the work of career artists. It sounded like a one-hit-wonder situation. Both members of Rae Sremmurd were in their early twenties when they first blew up, but they looked much younger, and their rise practically invited comparisons to that of Atlanta kiddie-rap icons and former Number Ones artists Kris Kross. If Rae Sremmurd disappeared completely after "No Flex Zone," nobody would've been surprised. Instead, the brothers followed that single with "No Type," which was just as catchy and which hit even harder, peaking at #16.

When Rae Sremmurd released their 2015 debut album SremmLife, I was shocked at how much I liked it. Virtually every song sounded like a hit, and many of them actually became hits. Five of the LP's 11 tracks eventually made the Hot 100, and the album went double platinum. SremmLife started fights, just because some rap commentators couldn't believe music this lightweight and immediate could also be great; I vividly remember Hot 97 figurehead Ebro haranguing my colleagues at Complex on-air after they put SremmLife near the top of a year-end list. Elsewhere in the industry, though, power players were paying attention. A Mike Will/Rae Sremmurd freestyle eventually evolved into "Formation," the instantly-iconic single that Beyoncé released early in 2016. ("Formation," which lists Swae Lee and Mike Will as songwriters, peaked at #10. It's a 10.)

Rae Sremmurd had a hot hand, and they wanted to keep their streak going. A year and a half after they released SremmLife, Rae Sremmurd finished work on SremmLife 2, the album's follow-up. But the early SremmLife 2 singles simply didn't connect the way that the SremmLife ones had. Lead single "By Chance" missed the Hot 100 entirely, while "Look Alive" peaked at #72. Just before its release, SremmLife 2 still needed a hit. Mike Will had just bought a new laptop, and he used it to sketch out the beginnings of a track and sent it over to Swae Lee. Swae freestyled a hook and sent the beat right back. When Mike Will got that hook, he happened to be over at his old collaborator Gucci Mane's house. Gucci accepted Mike Will's invitation to rap on the track, which means I get to write about Gucci Mane now.

I'll try to keep this compact since Gucci Mane's life story is way too rich for a few throwaway paragraphs in a Number Ones column, and since this week's column is already going to be plenty long. From an Atlanta perspective, Radric Delantic Davis is another Outta St8 Boy, born in Bessemer, Alabama. Davis' mostly-absent father was a slick-talking, well-dressed con man known as Gucci Man; his son simply adapted his nickname later on. (Gucci is more than a decade older than either of the Rae Sremmurd brothers. When he was born, Michael Jackson's "Rock With You" was the #1 song in America. So the two guys who made "Black Beatles" come from Elvis' hometown, and everyone on the track was born when a Jackson song was #1. We're just hitting all the pop icons here.)

Gucci Mane grew up between Alabama and East Atlanta. When he was in eighth grade, he spent his Christmas money on crack, which he sold at a markup. For years, Gucci sold drugs, getting into occasional legal trouble but also doing well for himself financially. At the time, Gucci had no musical aspirations. He loved rapping, and he'd pass the time coming up with rhymes while working, but he didn't think of music as a career path. He was already making too much money. After one jail stint, Gucci looked around for ways to clean up his street money. Taking inspiration from Southern rap moguls like Master P, Gucci figured that he could become a behind-the-scenes figure, and he started managing his nephew, a 14-year-old kid known as Lil Buddy. Gucci wrote Lil Buddy's rhymes and built a relationship with the local rap producer known as Zaytoven. When Lil Buddy drifted away from rapping, Zaytoven convinced Gucci to give it a shot himself, and he dropped his first mixtape in 2001.

For years, Gucci Mane sold drugs and mix CDs at the same time. Sometimes, he sold them together as a package deal. In 2004, the Atlanta snap crew Dem Franchize Boyz scored their first national hit with "White Tee," an ode to the gigantic T-shirts that street kids wore back then. ("White Tee" peaked at #79. Dem Franchize Boyz' highest-charting single, 2006's "Lean Wit It, Rock Wit It," peaked at #7. It's a 7.) Gucci Mane, already bubbling as a local rap figure, responded with "Black Tee," a crime-themed answer song that became an underground hit. A year later, Gucci Mane joined forces with Young Jeezy, another surging Atlanta underground rapper, for "Icy" a regional anthem that became the national breakout for both rappers.

We already got into Young Jeezy's story in the column on Usher's "Love In This Club," and that story includes the aftermath of "Icy." Both Gucci and Jeezy wanted to claim that song for their own, and it became a point of major contention, leading to an infamous rap feud. On a mixtape freestyle, Jeezy put out a bounty on Gucci's chain. Soon afterwards, Gucci was at a girl's house when four men burst in on him. Gucci shot at them, and the body of one of those men, a Jeezy-aligned rapper named Pookie Loc, was later discovered hastily buried behind a middle school. Gucci claimed self-defense, and local authorities declined to charge him with murder.

Gucci Mane became infamous as the rapper who had killed someone and gotten away with it. In his autobiography, Gucci later wrote that the episode left him traumatized and that he hated when people brought it up. Things between Gucci and Jeezy remained tense until the two did a pandemic-era Verzuz battle, finishing things up by rapping "Icy" together for the first time in years.

After "Icy," Young Jeezy became a full-on national star while Gucci remained an underground figure without much major-label muscle behind him. That suited Gucci just fine. He worked unbelievably quickly, and the mixtape underground gave him room to develop as a singular rap voice. In a years-long blitz of music, Gucci figured out his delivery, an oddly satisfying mushmouth bounce, and combined it with an imaginative and almost whimsical gift for bragging about his possessions and exploits. Gucci's street credentials were common knowledge, so he didn't have to talk about how tough he was. He could get playful. His lyrics were drunk on odd little details -- the glint of his diamonds, the colors of his cars, the way that a word like "gorgeous" or "wonderful" tasted in his mouth. By 2009, many of the smartest figures in rap's online cognoscenti agreed that Gucci Mane was the best rapper in the world.

During his insane mixtape run, Gucci Mane didn't really become a major chart figure. He didn't land on the Hot 100 until 2007, when his maddeningly memorable "Freaky Gurl" peaked at #62. On the Atlanta underground, though, Gucci was the man. Virtually every major rapper or producer who came up in that era got a boost from working with Gucci. Gucci was cranking out mixtapes so quickly that he needed a constant flow of beats and guest-verses, so young and untested producers like Mike Will got major looks. Entire generations of rappers, including plenty who will appear in this column, collaborated with Gucci early in their careers -- not just Atlanta stars like Future, Young Thug, and the Migos but also out-of-town figures like Nicki Minaj, Young Dolph, and Chief Keef. Gucci's backup guys OJ Da Juiceman and Waka Flocka Flame became stars in their own right, at least until they fell out with Gucci. But everyone always fell out with Gucci.

At the same time that he served as a crucial force on the Atlanta underground, Gucci Mane's life was spiraling out of control. He alienated many of his collaborators by cussing them out in a long Twitter rant. He had drug dependencies and violent tendencies. For a long time, he kept getting arrested for reckless driving and assault, often for physically attacking fans who came up to him to express their admiration. In 2011, he was ordered into a psychiatric hospital. When he got an ice cream cone tattooed on his face, it seemed like a sign that his grip on reality was becoming even more tenuous. (This was before virtually every prominent rapper and some country singers had multiple face tats.)

Before Gucci Mane got himself locked up, he started making hits. Gucci appeared on "Break Up," a song that former Number Ones artist Mario took to #14 in 2009, and on a remix of the Black Eyed Peas blockbuster "Boom Boom Pow." One of Gucci's own singles, the Plies collab "Wasted," made it to #36. But Gucci couldn't capitalize on any of his momentum because he was always in legal trouble. Finally, he pleaded guilty to gun possession in 2014, and he got sent to prison for a couple of years.

When Gucci Mane was in prison, something remarkable happened. Gucci cleaned up, lost a ton of weight, and changed his entire physical appearance and outlook on life. We don't hear stories like this too often, but Gucci actually got his shit together when he was incarcerated. When Gucci came home in 2016, there was an internet meme about how the government had killed the real Gucci Mane and replaced him with a more agreeable clone. That meme was mostly a joke, though it's always hard to tell with these things. Gucci reemerged from prison just as many of the rappers and producers he'd mentored were becoming stars, and it only seems right that he chanced his way onto a #1 hit. Gucci's "Black Beatles" verse is nowhere near his best work, but for those of us who love the guy, the song's success was the culmination of a real feelgood redemption story. (I promise you: This is the short version of the Gucci Mane history. I could've gone on way longer.)

"Black Beatles" isn't about the Beatles. The Beatles are barely even an idea on "Black Beatles." The track treats the Beatles as vaporous signifiers, links to a life of sex and drugs and attention and excitement. Two of the four get namedrops. Swae Lee: "I'm a fuckin' Black Beatle, cream seats in the Regal, rockin' John Lennon lenses, like to see 'em spread eagle." Slim Jxmmi: "I can't worry about a broke n***a or a hater/ Black Beatle, bitch, me and Paul McCartney related." The video makes vague references to Beatles iconography: the Abbey Road cover, the rooftop concert. Mostly, though, it's Rae Sremmurd playing around with guitars, on a song that features no guitars.

Swae Lee's beautifully airy "Black Beatles" hook never mentions anything Beatle-related. Instead, the title phrase evokes a feeling, a sense that these guys are living the partied-out famous-rocker lifestyle that actual rockers no longer lived by 2016. The Beatles' name functions much like that of Donald Trump on the 2014 Rae Sremmurd song "Up Like Trump" -- quite possibly the last rap song ever to use Trump's name as a catchall symbol of success. In the years that followed, a couple of Rae Sremmurd's rap peers would do away with references, putting out similarly sloshed #1 hits that were simply called "Rockstar." We'll get to those songs eventually, but "Black Beatles" definitely helped create a reality where those multiple songs called "Rockstar" could hit.

The great thing about "Black Beatles" is the track's sense of mostly-unspoken melancholy. All three of the rappers describe fantasy nightclub lifestyles where they're never not partying, but the music evokes the numb, bleary discontent that often comes with the lifestyle. A lot of that is down to the track. Mike Will's beat sparkles and twinkles like the best '80s synthpop. On the intro, eerie keyboard bloops float suspended before an oscillating bass-ripple comes in to hold everything together. There's no euphoric release when the drums drop in, since the programmed pattern is all jittery hesitation. And when Swae Lee's soft, tender tenor comes hovering into view, he sounds lost and tired.

In its way, "Black Beatles" works song for the peak of the party and for the comedown. If you're looking for pure euphoria, you can find it there. Anytime that one of the rappers snaps onto the beat, it brings a surge of energy. Slim Jxmmi, jumping onto the end of the track, sounds way more enthusiastic than anyone else; he really makes a meal out of his line about wearing leather Gucci jackets like it's still the '80s. It feels great to hear Gucci Mane on the track, but it's post-peak Gucci, operating on pure autopilot. Still, there's nothing like the way the bounce in his delivery builds shapes out of his slurry Southern accent. Near the end of his verse, Gucci starts to catch fire: "I Eurostep past a hater like I'm Rondo/ I upgrade ya baby mama to a condo." Even when Gucci treads water, his adlibs -- "nnnyeeeow" -- are dizzy fun.

"Black Beatles" doesn't sound much like the other big hits of 2016. It's not bright or clean or controlled, but it's also not the kind of twisty, guttural Atlanta trap that was thriving on the underground at the time. The Rae Sremmurd brothers never had any serious drug-dealing history, and they didn't load their tracks with heavy lingo and references. Instead, they talked about partying, a universal concern, and they brought enough silky melody to their music that it could work as crossover pop. Still, "Black Beatles" serves as a sleeker take on the sonic toolbox that Rae Sremmurd's mixtape-world peers used. The song wasn't built for pop radio, so its success was a little more surprising.

The calculus behind hit songs was changing. In 2015, streaming services like Spotify became the most reliable moneymaker in the business of recorded music, and they've retained that primacy ever since. As streaming services became more important, people migrated away from radio. Streaming algorithms and radio programmers used different criteria to pick which songs to push. Rap devotees, already used to consuming music on YouTube or on downloaded mixtapes, were early streaming-service adapters, and the charts swayed hard in the direction of rap over the next few years. "Black Beatles" was a bridge to that new reality. In my book, I wrote a chapter on "Black Beatles," and it's just because I thought it was funny to have a chapter about "Black Beatles" in the same book as one about the white Beatles. It's also because "Black Beatles" pointed a way forward for the streaming-era pop charts.

After Rae Sremmurd's first two SremmLife 2 singles bricked, there was no guarantee that "Black Beatles" would do any business, but the song took off on its own steam. The SremmLife 2 album came out in August 2016, and "Black Beatles" didn't reach the Hot 100 until the beginning of October. Still, the track was hazy and catchy enough to pick up momentum, and it was on its way up the chart when the Mannequin Challenge videos started happening.

At some point in 2016, a group of high school students in Jacksonville, Florida made a video where the entire class froze in place. It was fun, so they made more videos like that. The concept spread very quickly. In late October and early November, the Mannequin Challenge videos broke out of high schools and into the larger world. Pro sports teams posted their own Mannequin Challenge videos. TV news crews did it, and so did pop stars like Taylor Swift, Adele, and Destiny's Child, who reunited just so that Beyoncé could post that video. The cast of Saturday Night Live posted one. When the Cleveland Cavaliers visited the White House, LeBron James and Michelle Obama did a Mannequin Challenge. It was just like the "Harlem Shake" craze of 2013. But where that was gratingly silly, the Mannequin Challenge videos were eerie glimpses at a strange world where time refuses to move forward. They were fun, but they were also vaguely unsettling -- just like "Black Beatles."

No one did it better. RVHS ⚫️? #MannequinChallenge pic.twitter.com/QN8s0ulvq6

— uoɹɐɐ (@aaronzacharyh) November 5, 2016

Plenty of early Mannequin Challenge videos didn't have a soundtrack, but "Black Beatles" quickly became the default for people posting them. That kind of thing usually happens through mysterious means, and the combination of "Black Beatles" and the Mannequin Challenge started organically. In Ontario, California, one kid posted a Mannequin Challenge video set to the song. He later told The New York Times, "It’s my favorite song, and I wanted my friends and the internet to all hear it and enjoy it as well." The very next night, Rae Sremmurd played a show in Denver, and they got the entire club to film a Mannequin Challenge video with them.

#Mannequinchallenge livepic.twitter.com/y0aUTIfyTn

— Swae Lee Lee Swae (@SwaeLee) November 4, 2016

Within a few days, "Black Beatles" was all over virtually every Mannequin Challenge video. A rising hit met a rising internet fad, and magic happened. Some of that magic was willed into being by backroom suits. Interscope worked with an internet marketing firm called Pizzaslime to ensure that "Black Beatles" and the Mannequin Challenge would become forever linked in the public imagination. But PR firms don't have the power to manipulate the masses that easily. There was something about "Black Beatles" that fit just right with those videos. The gooey keyboards already sounded like they were trapped in time, and the undercurrents of menace and depression on "Black Beatles" fit the image of all these people stuck, unable to move. It's almost the inverse of a dance-craze hit. "Black Beatles" was what you heard when people were expressly discouraged from moving a muscle.

The Mannequin Challenge videos went mainstream in a hurry, and the phenomenon reached into unexpected places. Six days after Rae Sremmurd posted their Mannequin Challenge video, white Beatle Paul McCartney shared one of his own. His caption: "Love those Black Beatles." As the trend spread, streams and download sales of "Black Beatles" exploded. The song jumped from #9 to #1, and it held the spot long enough that the song couldn't be dismissed as a fad. As "Black Beatles" flew toward #1, the Atlanta Hawks held a Gucci Mane day. Gucci performed at halftime and got the arena to film a Mannequin Challenge video with him. During the game, Gucci also got down on one knee and proposed to his girlfriend; their wedding aired on BET the next year.

"Black Beatles" outlasted the Mannequin Challenge, which basically stopped being a thing in mid-November. The "Black Beatles" single held onto the #1 spot into the new year, and it's now nine times platinum. SremmLife 2, like its predecessor, went double platinum. Rae Sremmurd's follow-up single "Swang" peaked at #26, and they haven't been back in the top 10 -- not as a group, anyway -- since then. As a solo artist, Swae Lee will eventually appear in this column. Slim Jxmmi doesn't have any Hot 100 hits as lead artist, but he did ad-libs on a song that'll eventually show up here.

Gucci Mane hasn't been back in the top 10 after "Black Beatles," either, but he's come close a couple of times. In 2017, Gucci made it to #11 with "I Get The Bag," one of his collaborations with his proteges in the Migos. (The Migos will soon appear in this column.) A year later, Gucci was back at #11 with "Wake Up In The Sky" his song with Bruno Mars and Kodak Black. (Bruno Mars has been in this column a bunch of times, and he'll be back. Kodak Black doesn't have any #1 hits, but he directly inspired one, so he'll come up again.) Gucci is aging gracefully into a behind-the-scenes rap-elder type while still releasing a ton of music. He's mostly kept his shit together.

Rae Sremmurd followed SremmLife 2 with the ridiculous big-swing attempt SR3MM in 2018. SR3MM is a triple album: One solo record from Swae Lee, one from Slim Jxmmi, and one of the two of them together. That's like Speakerboxxx/The Love Below but somehow even more so, and it wasn't what the world wanted. SR3MM eventually went platinum -- easier to do when it's a triple album -- but its biggest hit, the Juicy J collab "Powerglide," peaked at #28. The duo got back together for last year's Sremm 4 Life, but none of its singles reached the Hot 100. Still, Rae Sremmurd's hitmaking streak lasted a lot longer than anyone expected. When those guys get old enough for the nostalgia circuit, I imagine they'll do really well. Given Swae Lee's hitmaking instincts, I wouldn't be surprised if he plays an active role in some more smashes, too.

The chart success of "Black Beatles" made something clear. The game had changed. Rappers no longer had to make obvious radio-crossover records. If the public heard something that it liked in a random album track, that random album track could become a viral smash on its own. If a song had some attachment to the meme economy, that could supercharge its success. In future columns, I'll cover a whole lot of songs that took off thanks to some internet challenge or other. Much like electoral politics, the pop charts are a more chaotic, unpredictable place now. "Black Beatles" had a lot to do with that.

GRADE: 9/10

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!

BONUS BEATS: Here's "Black Barbies," the "Black Beatles" freestyle that Nicki Minaj and Mike Will Made-It released in December 2016:

("Black Barbies" peaked at #65. Nicki Minaj will eventually appear in this column.)

The Number Ones: Twenty Chart-Topping Hits That Reveal The History Of Pop Music is out now on paperback via Hachette Books. That book is a real crowdpleaser. Buy it here.