If you think about it a certain way, one of the defining qualities of jazz is earnestness. This is one of the reasons why jazz and metal have so much in common, and so often appeal to the same listeners. Both forms can be totally absurd. Think of the most lurid, squiggly fusion, or the blare of a thoroughly unsubtle big band record; aren't they the equivalent of, say, DragonForce? But metal's awareness of its own absurdity does not translate into ironic distance from what they're doing. And the same is true of jazz. People will play the most ridiculous, over-the-top shit with a totally straight face. Even when a jazz group exhibits a certain amount of wit — think of the Bad Plus in their original incarnation, the version that covered "Smells Like Teen Spirit"; or Mostly Other People Do The Killing, and the way their sleeve designs imitated famous jazz album covers — it's done out of love, not mockery.

I recently saw a pretty amazing movie that made that earnestness into its crowning virtue. Blue Giant, an anime currently streaming on Netflix, is based on a long-running manga series of the same name, and it's a totally sincere story of three young Japanese men who form a jazz group and go forth on a quest to play Tokyo's most prestigious jazz club. Well, that's the pianist's personal quest; the saxophonist wants to be the greatest jazz musician on earth, and the drummer just wants to play music with his friends.

The interactions between the characters are what really sold me on Blue Giant, because from a plot standpoint, it's pretty straightforward. There are no side quests, and no big challenges (except at the very end). The saxophonist, Dai, comes to Tokyo from his small town with basically nothing but his horn and stands outside in the cold at night, practicing. He's genuinely talented and hard-working, but he doesn't know much about jazz beyond what he's heard on records, and he doesn't really know how to make music with other people. So when he connects with pianist Yukinori Sawabe, a player his own age who's already working with more experienced musicians, he's got a few things to learn. And if they're going to get gigs, they'll need a drummer, which is where Dai's friend and roommate, Shunji Tamada, comes in. He's never played the drums before, but he takes a few lessons (in a class full of little kids) and sets about to succeed through sheer determination. And he does actually get better; after one of their earliest performances, Sawabe tells him that he made so many mistakes he actually lost count, but a few gigs later, he's doing... less badly. And by the end of the movie, he's genuinely good.

Visually, the movie's great. Most of it is conveyed in a traditional anime style, but when the musicians are performing, it will sometimes switch to a more 3D form of CGI animation that makes the characters and their instruments, particularly Dai's horn, shimmer and glow. And during the most ecstatic musical moments, you'll get surreal, dreamlike images of flames, or the stars, or just explosions of light and color. Director Yuzuru Tachikawa said in an interview, "The main reason that led us to use 3D for concert scenes is the camerawork. I wanted to be able to reconstruct the most dynamic visual language and camera movements possible. It is more difficult to represent scenes of musical performance with traditional drawing, it requires a lot of time and a particular effort. It's really very long and delicate, so it also allowed us to keep control over the quality of the image."

This choice really draws you into the performances, several of which are offered at full length. And the music is great — it was written by pianist Hiromi Uehara, who also plays Yukinori's parts, while Dai, as heard, is actually saxophonist Tomoaki Baba. Drummer Shun Ishiwaka, who's played with trumpeter Adam O'Farrill and pianist Jason Moran, might actually have the toughest musical role, because like I said, when the movie starts, his character Tamada sucks, but he gradually gets better and better and delivers a pretty explosive solo during what turns out to be the trio's final performance.

Blue Giant is a movie that takes jazz seriously as an art form. Which means that you occasionally get some pretty corny dialogue about the meaning of jazz, but it's delivered by naive kids striving to make it, so you can tell yourself that sure, that would be their perspective. You also get to hear from jaded club bookers and pleasantly surprised audience members, though, who deliver realistic critique of the music. I found this to be a really interesting story about three friends hustling to make it, with some good plot twists I won't reveal here, terrific visuals, and a genuinely exciting soundtrack. Check it out; I don't think you'll regret it.

Here's "N.E.W.," which is the band's big number in the movie:

So here's the thing about the year-end list: I thought about what it would take to grind down the literally dozens of amazing records I heard this year into just 10 titles, and then rank them in order of quality, and I said, Nah, fuck that. What I have done instead is separated the year's jazz releases into 10 categories of my own devising, which are presented below in alphabetical order, and under each category heading you'll find five excellent records. As a reluctant concession to the whole list thing, there is a final selection ("If I Had To Pick Just One") for each category.

Archival Discoveries

Every year, tapes seem to fall out of the sky or off a radio station shelf, and producers who specialize in such sonic archeology do the work of commissioning scholarly liner note essays, tracking down memories from the surviving members of the relevant ensembles, getting present-day quotes from fellow musicians, unearthing rare photos, and most importantly of all, making the music sound as good as possible. This year, all the newly discovered jazz I responded to most strongly seemed to be in the free/avant-garde zone, even stuff by relatively mainstream players. The Black Artist Group's For Peace And Liberty – In Paris, Dec 1972 was only the second recording by the collective that gave the world saxophonist Oliver Lake, trumpeter Baikida Carroll, and many others. Alice Coltrane's The Carnegie Hall Concert was a grandiose spiritual jazz blowout from the queen of the genre, including both Archie Shepp and Pharoah Sanders on saxes alongside a double rhythm section (two bassists, two drummers) and traditional Indian instruments. Milford Graves, William Parker, and Charles Gayle's WEBO was a nuclear blast of early '90s freer-than-free jazz. Two of four sets Cecil Taylor recorded in February 1980 were released as Live At Fat Tuesday's February 9, 1980 First Visit and Live At Fat Tuesday's February 10, 1980 First Visit. (A third set was released in 1981 as It Is In The Brewing Luminous; I stole the title for my book In The Brewing Luminous: The Life & Music of Cecil Taylor, which came out in July.) And McCoy Tyner and Joe Henderson, with bassist Henry Grimes and drummer Jack DeJohnette, were heard on a blistering live recording from the legendary venue Slugs' from 1966.

If I Had To Pick Just One: Alice Coltrane, The Carnegie Hall Concert (Impulse!)

Leaders Of The New School

The 21st century has been a time of flux and redefinition for jazz, thanks to a generation of players who've mixed a love of bebop and swing with equally deep feelings for hip-hop, reggae, funk, Afrobeat and all the other sounds of the modern street. Saxophonist Melissa Aldana picked up the torch laid down by the late Wayne Shorter on Echoes Of The Inner Prophet, a Zenlike, introspective album featuring guitarist Lage Lund. Bassist Daniel Casimir, long the anchor of saxophonist Nubya Garcia's band, revealed himself as a composer of extraordinarily vivid big band-plus-orchestra music that managed to swing, groove, and bounce all at once on Balance. Saxophonist Isaiah Collier retired his band the Chosen Few with The World Is On Fire, a ferocious double LP of protest-themed, gospelized free jazz interspersed with recordings of news broadcasts and political commentary. Garcia herself released Odyssey, a brilliant expansion of her already thrilling fusion of spiritual jazz, funky hard bop, and dub that added strings and guest vocals (from esperanza spalding and Georgia Anne Muldrow, among others) to create an immersive life soundtrack. And Kamasi Washington, who brought jazz to an entirely new audience with 2015's The Epic, returned with his first album under his own name in six years; Fearless Movement was more soulful than his previous work, diving deep into electronics and hip-hop-inspired production while still foregrounding his powerful saxophone voice and anthemic songwriting.

If I Had To Pick Just One: Nubya Garcia, Odyssey (Concord Jazz)

New Age Spiritualists

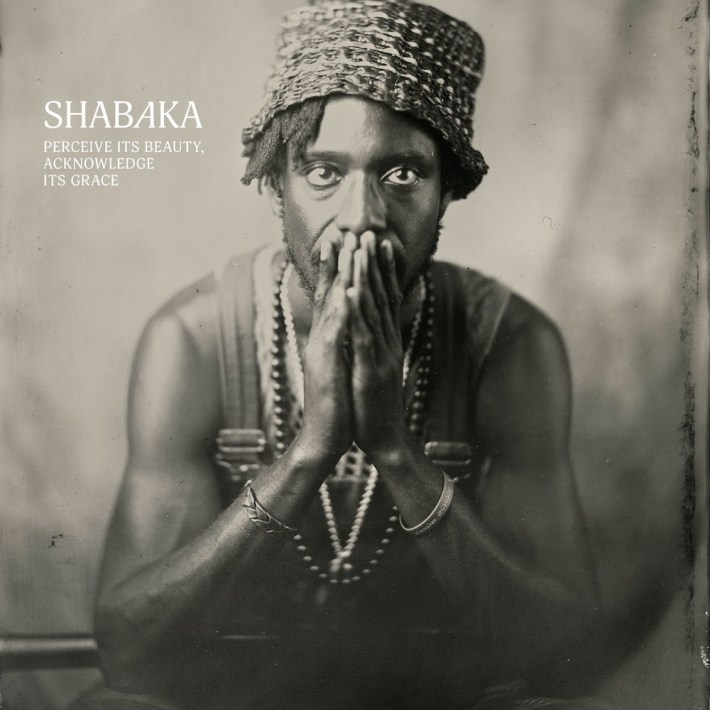

Wow, has this style of music exploded — or, more accurately, spread like aromatic mist — in the last few years. André 3000 brought a whole lot of people into the tent last year with his New Blue Sun project, but there's always been a blurry zone between spiritual jazz and New Age music; it's just hipper at the moment than it's been in a while. Three of the players behind New Blue Sun — keyboardist Surya Botofasina, guitarist Nate Mercerau, and percussionist Carlos Niño — released the aptly titled Subtle Movements in January. Shabaka Hutchings, now just Shabaka, abandoned the saxophone for flutes and gave us the gorgeous, meditative Perceive Its Beauty, Acknowledge Its Grace. Vocalist Ganavya released two albums: like the sky i've been too quiet (on Hutchings' Native Rebel label) and Daughter Of A Temple, on which she, pianist Vijay Iyer, and saxophonist Immanuel Wilkins paid tribute to Alice Coltrane, covering her "Om Supreme." And guitarist Jeff Parker and his ETA IVtet turned minimalist jamming into trance music on the four-track double LP The Way Out Of Easy, which documented the kind of alchemical "band voice" that can develop over the course of a years-long weekly residency.

If I Had To Pick Just One: Shabaka, Perceive Its Beauty, Acknowledge Its Grace (Impulse!)

The New Complexity

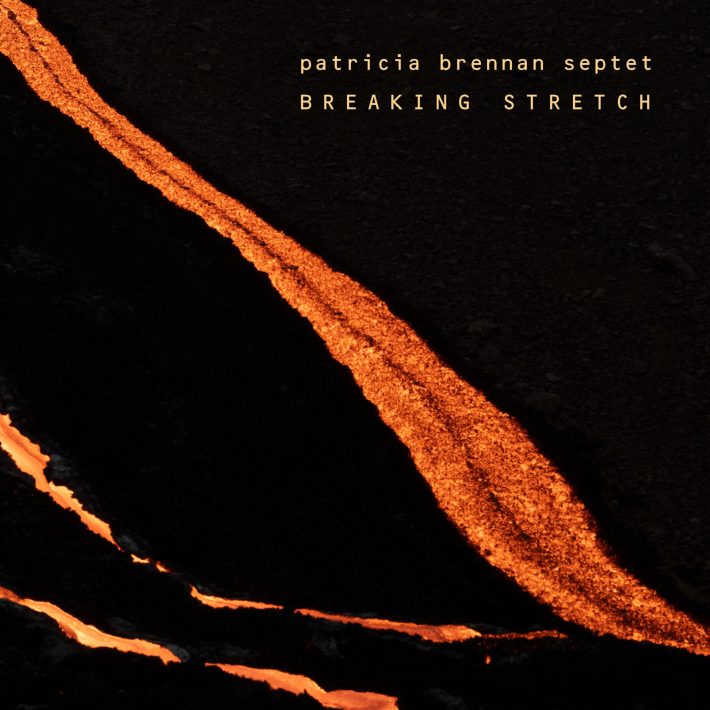

Some might say the rigorously composed music coming out of Brooklyn is the exact opposite of spiritual jazz. Call it cerebral jazz, perhaps? But at its best, this music is every bit as thrilling as the most fevered improvisation. Vibraphonist Patricia Brennan's Breaking Stretch put three horn players, bass, drums and percussion through their paces, creating a dizzying, densely layered suite of music. Bassist Kim Cass, who played on Breaking Stretch, released Levs, a set of complex, dark, eerie pieces featuring Matt Mitchell on piano and Tyshawn Sorey on drums, with horns adding droning atmospheres here and there. Mary Halvorson's Cloudward, a reunion of the band heard on 2022's Amaryllis, offered compositions that surged up and down like a tide, with Brennan's vibraphone more prominent than her own guitar. Mitchell's own album, Zealous Angles, featured hunt-and-peck melodies and cyclical rhythms that felt off right up till the moment they locked in, beautifully. Saxophonist Anna Webber's simpletrio2000, with Mitchell again and drummer John Hollenbeck, was pointillistic but cheerful, its precision so dialed-in you couldn't do anything but smile.

If I Had To Pick Just One: Patricia Brennan, Breaking Stretch (Pyroclastic)

The Nordics

As always, the northern European jazz scene (Sweden, Norway, Denmark and Finland) continues to punch well above its weight, and stretch the boundaries of what can be considered "jazz" at the same time. Some of this music is ice-cold, but some of it is red-hot, and all of it is extraordinarily beautiful. The Norwegian psychedelic organ trio Elephant9 teamed up with guitar legend Terje Rypdal (his '70s ECM albums are without exception masterpieces) for Catching Fire, an 80-minute live double LP that absolutely soars. Swedish saxophonist Elin Forkelid, often heard in loud avant-garde contexts, released the hushed and tender Songs To Keep You Company On A Dark Night accompanied by trumpet, guitar, upright bass, and no drums. The Finnish quartet Oaagaada mirror the lineup and the post-bebop exultation of the classic Ornette Coleman quartet (trumpet, saxophone, bass, drums); their debut album Music Of Oaagaada is less spiritual than holistic, recorded so that it seems part of the room where it was played. Swedish drummer Daniel Sommer teamed up with Norwegian trumpeter Arve Henriksen and Swedish bassist Johannes Lundberg for Sounds & Sequences, a series of improvised encounters that manifested as a kind of ambient spiritual chamber jazz. And Swedish pianist Lisa Ullén released the stunning solo disc Heirloom, exploring the same three pieces twice, once on each side of the LP.

If I Had To Pick Just One: Lisa Ullén, Heirloom (fönstret)

The Old-School Avant-Garde

Veterans continue to perform with the intensity of players half their age. Some of these artists have catalogs you'd need a year-long sabbatical to even make a dent in, but they continue to bring the heat every time. [ahmed], a quartet led by pianist Pat Thomas that pays tribute to bassist and composer Ahmed Abdul-Malik by turning his pieces into near hour-long journeys, released a single LP, Wood Blues, and the aptly named Giant Beauty, a 5CD box that comes at you like a steamroller. Saxophonist David Murray premiered a new quartet with pianist Marta Sanchez, bassist Luke Stewart, and drummer Russell Carter on the soulful, swinging but still blow-the-walls-down Francesca. Fellow saxophonist Ivo Perelman released several albums, as he does every year, but Embracing The Unknown featured two absolute legends as the rhythm section: bassist Reggie Workman and drummer Andrew Cyrille, and when you're working with former John Coltrane and Cecil Taylor sidemen, the potential for revelation is quite high. And trumpeter Wadada Leo Smith and pianist Amina Claudine Myers, who first recorded together in 1969 (on saxophonist Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre's Humility In The Light Of Creator), got back together for the piercing, gorgeous duo disc Central Park's Mosaics Of Reservoir, Lake, Paths And Gardens.

If I Had To Pick Just One: Wadada Leo Smith/Amina Claudine Myers, Central Park's Mosaics Of Reservoir, Lake, Paths And Gardens (Red Hook)

The Pianists

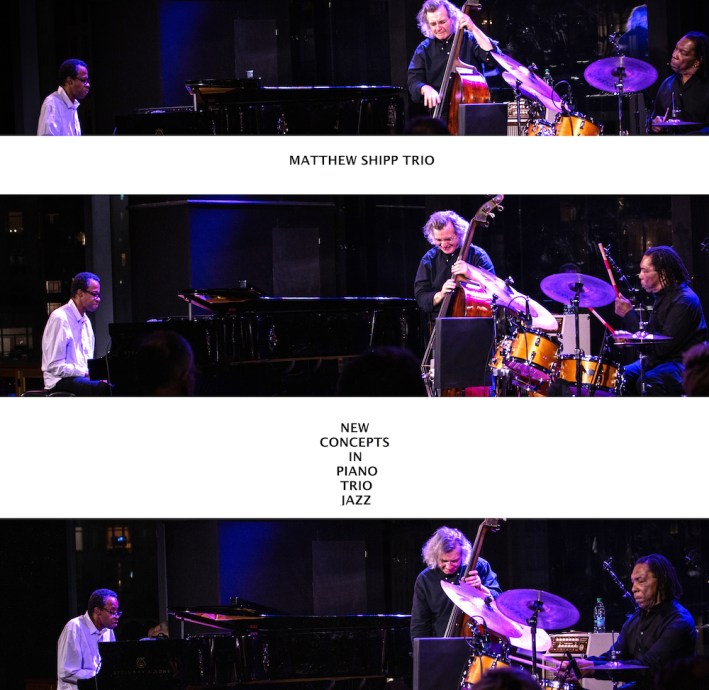

This has been an incredible year for jazz piano. The oldest player discussed here, George Cables, turned 80 in November, and celebrated with a tremendous album, I Hear Echoes, that mixes new and old originals with some of his favorite standards. Aaron Diehl records brilliantly on his own, but on The Susceptible Now, his third album with the Tyshawn Sorey Trio, he's engaged in some of the most fascinating deconstruction of "standards" in jazz history. Amaro Freitas is maybe the most percussive pianist since Cecil Taylor, and on Y'Y, he warps the instrument with dubby effects, joined by guests including Shabaka Hutchings, Jeff Parker, and harpist Brandee Younger. Vijay Iyer's trio with bassist Linda May Han Oh and Sorey returns with their second album, Compassion, a deep and heartfelt tribute to those now gone, including Iyer's father. And Matthew Shipp takes his trio — bassist Michael Bisio, drummer Newman Taylor Baker — into a dark and ominous realm on New Concepts In Piano Trio Jazz, blending free jazz and modern chamber music and in the process creating something genuinely unsettling, in the best possible way. It swings, too.

If I Had To Pick Just One: Matthew Shipp Trio, New Concepts In Piano Trio Jazz (ESP-Disk')

The South Africans

It took a little while for the world to notice, but South Africa has produced a generation of brilliant jazz musicians that almost makes up for also giving us Elon Musk. This year as always, they continued to present a thrilling challenge to peers around the globe, creating a truly African jazz that at its best will leave you with your mouth hanging open. Pianist Thembi Dunjana salutes her homeland with a two-horn quintet on God Bless iKapa. God Bless Mzantsi. (the isiXhosa words for Cape Town and South Africa, respectively), swinging in a way that blends hard bop and hip-hop. Drummer Asher Gamedze delivers an 80-minute manifesto on Constitution, performed by a 10-member ensemble that includes poet Fred Moten. Trombonist Malcolm Jiyane's Tree-O features many more than three musicians, and True Story is a collective portrait of South African jazz and avant-garde art as well as its folk culture, paying tribute to specific individuals via track names and multiple traditions in its head-spinning sound. Pianist Nduduzo Makhathini, who usually leads larger groups, made uNomkhubulwane with just a trio, and its three multi-part suites feel like meditative rituals. Makhathini also plays on saxophonist Linda Sikhakhane's Blue Note debut, iLadi, a stunning quartet disc that asks the question, What if John Coltrane had recorded Crescent in Cape Town?

If I Had To Pick Just One: Thembi Dunjana, God Bless iKapa. God Bless Mzantsi. (AfricArise/Ropeadope)

The Traditionalists

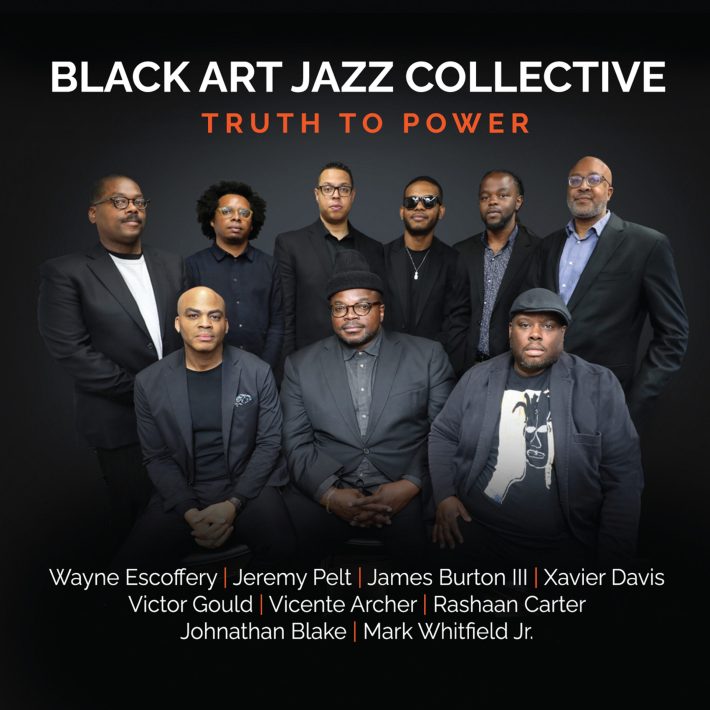

This could also be called the "Jazz That Sounds Like Jazz" category. All five albums here offer melodic, swinging music played by musicians in total technical command of their instruments. Listen to them with the romantic partner of your choice, or your mom. Saxophonist JD Allen's The Dark, The Light, The Grey & The Colorful offers deep, bluesy tunes, performed with two bassists (one acoustic, one electric) and drums; it has an eerie and unsettled feeling at times, and the continuity of a single work in 12 movements. The Black Art Jazz Collective, co-led by saxophonist Wayne Escoffery and trumpeter Jeremy Pelt for a decade, celebrated that anniversary with Truth To Power, on which they brought back everyone who's ever played in the band for a collection of high-level compositions in the tradition of the finest acoustic jazz, and introduced some new faces as well (Pelt has since departed). Alto saxophonist Charles McPherson released Reverence, a collection of taut, high-energy hard bop on which he trades solos with trumpeter Terrell Stafford in a way that will remind you of classic 1960s Blue Note albums. Drummer Brandon Sanders follows up last year's Compton's Finest with The Tables Will Turn, a collection of standards and originals on which vibraphonist Warren Wolf takes many of the most exciting solos. And trumpeter David Weiss, best known for leading the all-star band the Cookers, assembles a killer hard bop sextet on Auteur, playing gorgeous new compositions that pay tribute to George Cables, Wayne Shorter, and Art Blakey.

If I Had To Pick Just One: The Black Art Jazz Collective, Truth To Power (HighNote)

What Do You Even Call That?

The albums under this heading are more jazz-adjacent than strictly jazz, and they incorporate a vast array of sounds and production techniques; you're likely to hear something you've never heard before in your life while exploring these. Composer Rosanna Gunnarsson and pianist Karin Johansson collaborated on I grunda vikar är bottnarna mjuka, a fascinating album that combines field recordings from a Swedish archipelago bay with the sound of a piano being lowered into the water, plus Johansson's prepared piano improvisations; it's literally immersive, so listen on headphones. Meanwhile, indefatigable tenor saxophonist James Brandon Lewis teamed up with the Messthetics (guitarist Anthony Pirog and bassist and drummer Joe Lally and Brendan Canty, formerly of Fugazi) for a self-titled collection of pieces that blur the lines between spiky prog rock and swaggering jazz-funk. Moor Mother's The Great Bailout is a mournful, unflinching examination of the UK's role in the global slave trade, an indictment of that country's continuing worship of its creepy royal family, and much more; it features instrumental contributions from Vijay Iyer, trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire, harpist Mary Lattimore, and multiple vocalists. Nala Sinephro's second album, Endlessness, is a 10-movement, 45-minute suite of womblike synths, harp, horns (Nubya Garcia plays saxophone on several tracks), gently ticking drums...play it as you float in your isolation tank. (What, you don't own one?) Finally, Colin Stetson's The Love It Took To Leave You is an astonishing collection of solo pieces performed live, with no overdubs, on alto and bass saxophones and contrabass clarinet, but thanks to a complex system of multiple microphones (some of them extremely close) it's like living inside a saxophone the size of a grain silo; when he strikes a key, it's like a bank vault door slamming shut on your skull.

If I Had To Pick Just One: Nala Sinephro, Endlessness (Warp)

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!